HNA April 2013 Cover.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plekken Van Plezier

Plekken van plezier Open Monumentendagen 14 & 15 september Haarlem - 1 Welkom in Haarlem Op de voorkant van dit programmaboekje prijkt zwembad De Houtvaart. Een prachtige plek van plezier in onze monumentenstad Haarlem. Dit jaar staat dan ook de amusementswaarde van monumenten centraal tijdens Open Monumentendagen, met als thema ‘Plekken van plezier’. Naar welke monumentale plekken gingen en gaan mensen voor hun plezier? Ik vind het belangrijk dat onze monumenten bewaard en beschermd blijven. Dat ze bezocht en bewonderd kunnen worden en dat ze ons leren wie we zijn en waar we vandaan komen. Veel vrijwilligers werken actief mee aan de organisatie en uitvoering van de Open Monumentendagen; vanaf deze plek wil ik iedereen hartelijk bedanken voor hun inzet. In dit boekje vindt u informatie over bijzondere monumenten in Haarlem die hun deuren voor u openen. Een mooie selectie van monumenten voor ontspanning, vermaak en vrije tijd. Ik wens u een plezierig weekend vol verrassende ervaringen toe! Floor Roduner, wethouder Monumenten en Erfgoed - 2 Plekken van plezier Hoe hebben mensen zich in de loop der eeuwen vermaakt en welke monumenten zijn daarvoor het decor of het podium geweest? Deze vragen zijn leidend geweest bij het samenstellen van dit programma boekje. In Haarlem zijn volop historische ‘plekken van plezier’ te vinden zoals theaters, musea, parken, markten en sportclubs. Al in de middeleeuwen zijn er plekken in Haarlem aan te wijzen die centraal staan voor vermaak. Zo had Haarlem als eerste stad ter wereld een heus sportveld, de ‘Baen’. Hier werden vanaf de 14de eeuw Oudhollandse spellen gespeeld. Een andere bekende plek van plezier is de Haarlemmerhout, een immense groene oase aan de zuidkant van de stad. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine Macleod and Alexa

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr British Art Studies Issue 17, published 30 September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr Cover image: Left portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1605, watercolour on vellum, laid onto table-book leaf, 5.7 x 4.4 cm. Collection of National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 3063); Right portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1603, watercolour on vellum, laid on card, 4.9 x 4 cm. Collection of Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (FM 3869). Digital image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London (All rights reserved); Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (All rights reserved). PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Antwerp in 2 Days | the Rubens House

Antwerp in 2 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect Rubens was talented in many areas of life. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. On your way to Hendrik Conscienceplein, we would suggest you make a brief stop at another church: St James’s Church (St Jacobskerk) in Lange Nieuwstraat. This robust building dooms up rather unexpectedly among the houses, but its interior presents a perfect harmony between Gothic and Baroque: the elegant Middle Ages and the flamboyant style of the 17th century go hand-in-hand here. -

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

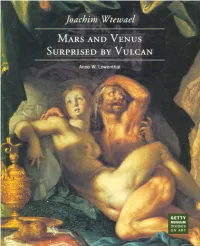

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

Rubenianum Fund Field Trip to Princely Rome, October 2017

2017 The Rubenianum Quarterly 3 Peter Paul Rubens: The Power of Transformation Drawn to drawings: a new collaborative project Mythological dramas and biblical miracles, intimate portraits and vast landscapes – Although the Rubenianum seldom seeks the Peter Paul Rubens’s creative power knew no limits. His ingenuity seems inexhaustible, public spotlight for its scholarship, specialists and his imagination boundless. The special exhibition ‘Kraft der Verwandlung’ institutions in the field know very well where to turn (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 17 October 2017–21 January 2018) sets out to to for broad, grounded and reliable art-historical explore this spirit of innovation, taking an in-depth look at the sources on which the expertise. Earlier this year, the Flemish Government Flemish master drew and how he made them his own. approached us with a view to a possible assignment Rubens had an unrivalled ability to apply his examples freely and creatively. concerning 17th-century drawings. Given that Ignoring the boundaries of genre, he studied the small-scale art of printmaking as well another of the Rubenianum’s unmistakable as monumental oil paintings. The artist’s extensive library provided a further source trademarks is its open and generous attitude to of inspiration, as did antique coins. He took three-dimensional sculptures – bronze statuettes, casts from nature and marble statues – and brought them to life in his collaboration, this task was indeed assigned to paintings. us thanks to a thoroughly prepared partnership Rubens drew, copied and interpreted as he saw fit throughout his life. Existing with the Royal Library of Belgium. We are proud, sources were transformed by his hand into something entirely new. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

Cornelis Cornelisz, Who Himself Added 'Van Haarlem' to His Name, Was One of the Leading Figures of Dutch Mannerism, Together

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Haarlem 1562 – 1638) Venus, Cupid and Ceres Oil on canvas 38 x 43 in. (96.7 x 109.2 cm.) Signed with monogram and dated upper right: ‘CH. 1604’ Provenance Private collection, New York Cornelis Cornelisz, who himself added ‘van Haarlem’ to his name, was one of the leading figures of Dutch Mannerism, together with his townsman Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert from Utrecht. He was born in 1562 in a well-to-do Catholic family in Haarlem, where he first studied with Pieter Pietersz. At the age of seventeen he went to France, but at Rouen he had to turn back to avoid an outbreak of the plague and went instead to Antwerp, where he remained for a year with Gilles Coignet. The artist returned to Haarlem in 1581, and two years later, in 1583, he received his first important commission for a group portrait of a Haarlem militia company (now in the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem). From roughly 1586 to 1591 Cornelis, together with Goltzius and Flemish émigré Karel van Mander formed a sort of “studio brotherhood” which became known as the ‘Haarlem Academy’. In the 1590’s he continued to receive many important commissions from the Municipality and other institutions. Before 1603, he married the daughter of a Haarlem burgomaster. In 1605, he inherited a third of his wealthy father-in-law’s estate; his wife died the following year. From an illicit union with Margriet Pouwelsdr, Cornelis had a daughter Maria in 1611. -

Call for Justice Museum Hof Van Busleyden Mechelen

Call for Justice Museum Hof van Busleyden Mechelen 23 MARCH - 24 JUNE 2018 ART AND LAW IN THE NETHERLANDS (1450-1650) Justice and injustice are two of the most prominent themes during the Golden Age of Netherlandish art in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth century. The dukes of Burgundy wanted to combine their territories in the Netherlands into one political entity, which in turn occasioned sweeping changes to the judicial system. They established central institutions, such as the Great Council of Mechelen, thereby effectively curtailing the authority of the local courts. While the legal process became more professional, it also became more cumbersome and less accessible. The discovery of the New World, the Dutch Revolt and the Spanish Inquisition unleashed a rampage of unprecedented horror. People who were different or held a different opinion were cruelly punished. Almost all the important painters of this period, from Rogier van der Weyden to Antoon van Dyck and Rembrandt all focused on the themes of justice, injustice and law in their work. They were inspired by examples of righteous behaviour in Biblical stories, allegories, myths and history. Their artworks show how crime is punished and provide solace for injustice. Contemporary abuses are mocked and denounced. The art of justice and injustice was used to decorate town halls and churches, and also penetrated the domestic sphere, mainly through books and prints. 1. Maarten de Vos The Tribunal of the Brabant Mint in Antwerp 1546 – KBC Snijders&Rockoxhuis, Antwerp © KBC Antwerpen Snijders&Rockoxhuis This painting almost serves as an introduction to the sixteenth-century iconography LADY JUSTICE of law.