Passages Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P36-40Spe Layout 1

lifestyle THURSDAY, JANUARY 15, 2015 Music & Movies Madonna, AC/DC to play Grammys ceremony op icon Madonna and veteran hard rockers AC/DC The Grammys also tapped heavy metal veterans last will join younger stars in performing at the Grammys year with a performance by Metallica, who played the 25- Pon February 8, organizers of the music industry’s pre- year-old song “One” with classical pianist Lang Lang. mier awards show announced Tuesday. Other musicians Another musician scheduled to play this year’s Grammys is chosen to play at one of the year’s most-watched concerts the country star Eric Church, who is in contention for four include the English singer and songwriter Ed Sheeran, awards. — AFP whose “X” is up for the Grammys’ prestigious Album of the Year, and the child star turned pop singer Ariana Grande, who is nominated in two categories. Madonna, who has won seven Grammys over her three- decade career, is scheduled in March to release a new album, “Rebel Heart,” in which she goes further in a hip- hop direction. She abruptly released six songs from the album in December after versions leaked on the Internet. Madonna, who has a large following in the gay community, also played the Grammys last year in a surprise move, join- ing Macklemore and Ryan Lewis in their same-sex marriage anthem, “Same Love,” as 33 couples of diverse backgrounds got married on the Grammys floor in Los Angeles. AC/DC will take the stage after tumult among the veter- an Australian hard rockers as drummer Phil Rudd faced allegations of hiring a hitman in New Zealand and found- ing member Malcolm Young retired to a special care home as he suffers dementia. -

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

Af20-Booking-Guide.Pdf

1 SPECIAL EVENT YOU'RE 60th Birthday Concert 6 Fire Gardens 12 WRITERS’ WEEK 77 Adelaide Writers’ Week WELCOME AF OPERA Requiem 8 DANCE Breaking the Waves 24 10 Lyon Opera Ballet 26 Enter Achilles We believe everyone should be able to enjoy the Adelaide Festival. 44 Between Tiny Cities Check out the following discounts and ways to save... PHYSICAL THEATRE 45 Two Crews 54 Black Velvet High Performance Packing Tape 40 CLASSICAL MUSIC THEATRE 16 150 Psalms The Doctor 14 OPEN HOUSE CONCESSION UNDER 30 28 The Sound of History: Beethoven, Cold Blood 22 Napoleon and Revolution A range of initiatives including Pensioner Under 30? Access super Mouthpiece 30 48 Chamber Landscapes: Pay What You Can and 1000 Unemployed discounted tickets to most Cock Cock... Who’s There? 38 Citizen & Composer tickets for those in need MEAA member Festival shows The Iliad – Out Loud 42 See page 85 for more information Aleppo. A Portrait of Absence 46 52 Garrick Ohlsson Dance Nation 60 53 Mahler / Adès STUDENTS FRIENDS GROUPS CONTEMPORARY MUSIC INTERACTIVE Your full time student ID Become a Friend to access Book a group of 6+ 32 Buŋgul Eight 36 unlocks special prices for priority seating and save online and save 15% 61 WOMADelaide most Festival shows 15% on AF tickets 65 The Parov Stelar Band 66 Mad Max meets VISUAL ART The Shaolin Afronauts 150 Psalms Exhibition 21 67 Vince Jones & The Heavy Hitters MYSTERY PACKAGES NEW A Doll's House 62 68 Lisa Gerrard & Paul Grabowsky Monster Theatres - 74 IN 69 Joep Beving If you find it hard to decide what to see during the Festival, 2020 Adelaide Biennial . -

Deconstructing David Lang's the Anvil Chorus

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2014 Deconstructing David Lang's The Anvil Chorus Brandon M. Smith Columbus State University Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Brandon M., "Deconstructing David Lang's The Anvil Chorus" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 113. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/113 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Deconstructing David Lang's The Anvil Chorus by Brandon Michael Smith A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Degree of Bachelor of Music in Music Education College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Committee Member Dr. Sean Powell Honors Committee Member J&^^ f Date [g^SjLS ' Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Honors Program Director ^trkO^h^C^^ Date £&Q indy Ticknor 1 Usually, when a piece of music is taken out of context, that is, when it is learned and performed without studying the piece, the composer, the musical genre, or the historical significance, the understanding of it for the performer is narrow and limited and the performance is less than ideal. This leads to a substandard realization of the music. Contrarily, a musician should integrate research with the learning process as to enhance the comprehensive understanding of the piece, which ultimately results in a high level of performance. This idea is important for the complex and extensive musical repertoire of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Michel Van Der Aa Appears Tobenothingparticularlyradicalaboutit

Excerpt from the score of Here [to be found]. ‘This is the Gesamtkunst of the future.’ The Financial Times on After Life An Introduction to the Music cryptic suffering. As a dramatized documentary about a of Michel van der Aa genre it is quintessential Van der Aa. He is the observer whose expedition begins with the vital life questions his by Bas van Putten characters pose on his behalf. What do I see and hear, who am I, what do I feel, what do I think, where do I At first glance, Spaces of Blank (2007) by the Dutch stand? His brand of composing – and in the meantime, composer Michel van der Aa appears to be a conven- much more than just that: Van der Aa also films and tional three-movement song cycle for mezzo-soprano, directs – is less a matter of style as of attitude. ‘I’m not orchestra and soundtrack. The work, written on a a composer of just notes,’ he once said. Although he commission from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, willingly qualifies that statement (‘not that notes aren’t Radio France and the Norddeutscher Rundfunk, is a important’), music is for Van der Aa unmistakably part of setting of evocative poems by Emily Dickinson, Anne a larger whole. The immediate recognizability of his tone, Carson and Rozalie Hirs; it is scored for more or less with the typical alternation between hectic motion and standard orchestral forces; the solo part is, for the most serene, surprisingly sonorous electro-acoustic harmo- part, without vocal eccentricities. Less common is the nies, does nothing to diminish this assertion. -

6Th European Music Analysis Conference – VII

6th European Music Analysis Conference – VII. Jahreskongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie Druck: Rombach Druck- und Verlagshaus GmbH & Co KG, Freiburg Redaktion: Prof. Ludwig Holtmeier Jens Awe Torang Sinaga Satz/Layout: Miriam Rieckmann Torang Sinaga Redaktionsadresse: Studium generale Belfortstr. 20, 79085 Freiburg Anfahrtsbeschreibung und Übersicht der Veranstaltungsorte Universität Freiburg Kollegiengebäude (KG) „Haus zur Lieben Hand“, Br eis Löwenstr.16 ac h . e r r S P t t s Domsingschule r. r e g Hochschule für Musik r u b s b P a H . Fahnen- B3 tr s DB bergpl. r e Freiburg L re ß e eo e a le p t r Hbf. l o in t a ld s ri W k r. ng lz c t r S o P Rotteckr. - h Be h g h ma rto P p in c lds B3 e r is tr. s A s o Münster rg u E B J to Werth- - e ba r b h mann- e s n s S s zu i alzs P o b Belfor Pl. a tr. l Schlossberg r tstr. K h in c g . er r g S M b n P it i AltstadtSchwaben- te in r l r torpl. w e e d r Kartäuserstr n . e h L c W eo -W S B31 o indenburgstr. D S h H b c r . reisam Dreisamstr. hw le r b g a -S st rz ß Hochschule . w tr unzstr. n r Schillerstr. a . R o l e t lds für Musik s tr. F n . -

Garth Brooks. the Life of Chris Gaines Free Download Garth Brooks

garth brooks. the life of chris gaines free download Garth brooks. the life of chris gaines free download. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #44e3ed50-f665-11eb-94e5-7912fe89ce48 VID: #(null) IP: 188.246.226.140 Date and time: Fri, 06 Aug 2021 03:20:37 GMT. The Untold Truth Of Chris Gaines. In 1999, Garth Brooks was on top of the country music world. He decided to tackle rock next—but rather than just release a Garth Brooks rock album, he created an elaborate character named Chris Gaines. Sporting a soul patch and a long black wig, "Chris Gaines" was envisioned as the Ziggy Stardust to Brooks' David Bowie. In reality, he became the biggest embarrassment of Brooks' career. Here's a look at one of the weirdest episodes in music history. Gaines' only album was a "greatest hits" compilation. Garth Brooks didn't simply put out Chris Gaines' purported debut album—he released a Gaines greatest hits compilation. If it wasn't already confusing enough for fans wondering why Brooks was dressed like a goth teenager, he made it worse by pretending that people were supposed to have already heard of his alter ego. Creatively titled Chris Gaines' Greatest Hits , the album was supposedly the highlights of highly successful solo albums like Gaines' "debut," Straight Jacket , whose cover featured Gaines pictured in a straightjacket—flanked by naughty nurses, as is a rock star's wont. -

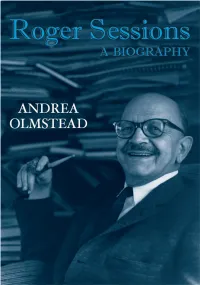

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Mcallister Interview Transcription

Interview with Timothy McAllister: Gershwin, Adams, and the Orchestral Saxophone with Lisa Keeney Extended Interview In September 2016, the University of Michigan’s University Symphony Orchestra (USO) performed a concert program with the works of two major American composers: John Adams and George Gershwin. The USO premiered both the new edition of Concerto in F and the Unabridged Edition of An American in Paris created by the UM Gershwin Initiative. This program also featured Adams’ The Chairman Dances and his Saxophone Concerto with soloist Timothy McAllister, for whom the concerto was written. This interview took place in August 2016 as a promotion for the concert and was published on the Gershwin Initiative’s YouTube channel with the help of Novus New Music, Inc. The following is a full transcription of the extended interview, now available on the Gershwin channel on YouTube. Dr. Timothy McAllister is the professor of saxophone at the University of Michigan. In addition to being the featured soloist of John Adams’ Saxophone Concerto, he has been a frequent guest with ensembles such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Lisa Keeney is a saxophonist and researcher; an alumna of the University of Michigan, she works as an editing assistant for the UM Gershwin Initiative and also independently researches Gershwin’s relationship with the saxophone. ORCHESTRAL SAXOPHONE LK: Let’s begin with a general question: what is the orchestral saxophone, and why is it considered an anomaly or specialty instrument in orchestral music? TM: It’s such a complicated past that we have with the saxophone. -

Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from JS Bach's

Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Johann Jacob Van Niekerk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Giselle Wyers, Chair Geoffrey Boers Shannon Dudley Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2014 Johann Jacob Van Niekerk University of Washington Abstract Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Giselle Wyers Associate Professor of Choral Music and Voice The themes of suffering and social conscience permeate the history of the sung passion genre: composers have strived for centuries to depict Christ’s suffering and the injustice of his final days. During the past eighty years, the definition of the genre has expanded to include secular protagonists, veiled and not-so-veiled socio- political commentary and increased discussion of suffering and social conscience as socially relevant themes. This dissertation primarily investigates David Lang’s Pulitzer award winning the little match girl passion, premiered in 2007. David Lang’s setting of Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl” interspersed with text from the chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) has since been performed by several ensembles in the United States and abroad, where it has evoked emotionally visceral reactions from audiences and critics alike. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music.