Contents Perspectives in History Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Green Leaves of China. Sociopolitical Imaginaries in Chinese Environmental Nonfiction

The green leaves of China. Sociopolitical imaginaries in Chinese environmental nonfiction. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Institut für Sinologie Vorgelegt von Matthias Liehr April 2013 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rudolf G. Wagner Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Barbara Mittler Table of contents Table of contents 1 Acknowledgements 2 List of abbreviated book titles 4 I. Introduction 5 I.1 Thesis outline 9 II. Looking for environmentalism with Chinese characteristics 13 II.1 Theoretical considerations: In search for a ‘green public sphere’ in China. 13 II.2 Bringing culture back in: traditional repertoires of public contention within Chinese environmentalism 28 II.3 A cosmopolitan perspective on Chinese environmentalism 38 III. “Woodcutter, wake up”: Governance in Chinese ecological reportage literature 62 III.1 Background: Economic Reform and Environmental Destruction in the 1980s 64 III.2 The narrative: Woodcutter, wake up! – A tale of two mountains, and one problem 68 III.3 The form: Literary reportage, and its role within the Chinese social imaginary 74 III.4 The subject matter: Naturescape and governance 86 IV. Tang Xiyang and the creation of China’s green avant-garde 98 IV.1 Beginnings: What nature? What man? 100 IV.2 A Green World Tour 105 IV.3 Back in China: Green Camp, and China’s new green elite 130 V. Back to the future? Ecological Civilization, and the search for Chinese modernity 144 V.1 What is “Ecological Civilization”? 146 V.2 Mr. Science or Mr. Culture to the rescue? 152 VI. The allure of the periphery: Cultural counter-narratives and social nonconformism 182 VI.1 The rugged individual in the wilderness: Yang Xin 184 VI.2 Counter-narratives and ethnicity discourse in 1980s China 193 VI.3 A land for heroes 199 VI.4 A land of spirituality 217 VII. -

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

The King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles Introduction Further to my article on The Battle of Tanga - 1914, I have studied the various African units participating in the First World War, and here follows a brief overview of one of the most famous African units - The King's African Rifles. The King's African Rifles, ca. 1916 1). Regimental Badge The King's African Rifles. From Regimental Badges by T.J. Edwards, Gale & Polden Limited, 1951. Formation The regiment was formed on 1 January 1902, and combined a number of units from various British East African dependencies - Somaliland, British East Africa (from July 1920: Kenya), Uganda and Nyasaland. At the formation, The King's African Rifles included the following battalions, which in principle existed until the independence of the various colonies in the 1960'ies. King's African Rifles2) Derived from Remarks 1st (Central Africa) 1st Battalion Central Africa Regiment. The Malawi Rifles (1964) Battalion 2nd (Central Africa) 2nd Battalion Central Africa Regiment Disbanded in 1962 Battalion 3rd (East Africa) Battalion East Africa Rifles (British East Africa) The Kenya Rifles (1963) 4th (Uganda) Battalion Uganda Rifles, from various African The Uganda Rifles (1962) companies 5th (Uganda) Battalion Uganda Rifles, from various Indian The Kenya Rifles (1963) companies 6th (Somaliland) Battalion Raised by local units in Somaliland Disbanded in 1910 6th (Tanganyika) Battalion Formed from ex-German askaris in 1917-18 The Tanganyika Rifles (1961) At the formation the regiment included 4.683 men, including 104 British officers. During the First World War the regiment grew into 22 battalions, consisting in July 1918 of 1,193 British Officers, 1,497 British Non-Commissioned Officers, and 30.658 Africans. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

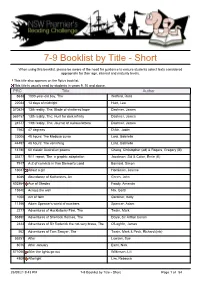

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title Author 5638 1000-year-old boy, The Welford, Ross 22034 13 days of midnight Hunt, Leo 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Dashner, James 569157 13th reality, The: Hunt for dark infinity Dashner, James 24577 13th reality, The: Journal of curious letters Dashner, James 7562 47 degrees D'Ath, Justin 23006 48 hours: The Medusa curse Lord, Gabrielle 44497 48 hours: The vanishing Lord, Gabrielle 14780 60 classic Australian poems Cheng, Christopher (ed) & Rogers, Gregory (ill) 33477 9/11 report, The: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Sid & Colon, Ernie (ill) 7917 A-Z of convicts in Van Diemen's Land Barnard, Simon 16047 About a girl Horniman, Joanne 8086 Abundance of Katherines, An Green, John 602864 Ace of Shades Foody, Amanda 15540 Across the wall Nix, Garth 1058 Act of faith Gardiner, Kelly 11356 Adam Spencer's world of numbers Spencer, Adam 2277 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 55890 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan 2444 Adventures of Sir Roderick the not-very brave, The O'Loghlin, James 562 Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark & Peck, Richard (intr) 55251 After Lawson, Sue 8076 After January Earls, Nick 571050 After the lights go out Wilkinson, Lili 4809 Afterlight Lim, -

Violence and Predation, Mainly in the Form of Piracy, Were Two Of

violence and predation robert j. antony Violence and Predation on the Sino-Vietnamese Maritime Frontier, 1450–1850 iolence and predation, mainly in the form of piracy, were two of V the most persistent and pervasive features of the Sino-Vietnamese maritime frontier between the mid-fifteenth and mid-nineteenth cen- turies.1 In the Gulf of Tonkin, which is the focus of this article, piracy was, in fact, an intrinsic feature of this sea frontier and a dynamic and significant force in the region’s economic, social, and cultural devel- opment. My approach, what scholars call history from the bottom up, places pirates, not the state, at center stage, recognizing their impor- tance and agency as historical actors. My research is based on various types of written history, including Qing archives, the Veritable Records of Vietnam and China, local Chinese gazetteers, and travel accounts; I also bring in my own fieldwork in the gulf region conducted over the past six years. The article is divided into three sections: first, I discuss the geopolitical characteristics of this maritime frontier as a background to our understanding of piracy in the region; second, I consider the socio-cultural aspects of the gulf region, especially the underclass who engaged in clandestine activities as a part of their daily lives; and third, I analyze five specific episodes of piracy in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Gulf of Tonkin (often referred to here simply as the gulf), which is tucked away in the northwestern corner of the South China Sea, borders on Vietnam in the west and China in the north and east. -

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918)

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918) Nuno Lemos Pires1 https://academiamilitar.academia.edu/NunoPires At the onset of the Great War, none of the colonial powers were prepared to do battle in Africa. None had stated their intentions to do so and there were no indications that one of them would take the step of attacking its neighbours. The War in Africa has always been considered a secondary theatre of operations by all conflicting nations but, as well shall see, not by the political discourse of the time. This discourse was important, especially in Portugal, but the transition from policy to strategic action was almost the opposite of what was said, as we shall demonstrate in the following chapters. It is both difficult and deeply simple to understand the opposing interests of the different nations in Africa. It is difficult because they are all quite different from one another. It is also deeply simple because some interests have always been clear and self-evident. But we will return to our initial statement. When war broke out in Europe and in the rest of the World, none of the colonial powers were prepared to fight one another. The forces, the policy, the security forces, the traditions, the strategic practices were focused on domestic conflict, that is, on disturbances of the public order, local and regional upheaval and insurgency by groups or movements (Fendall, 2014: 15). Therefore, when the war began, the warning signs of this lack of preparation were immediately visible. Let us elaborate. First, each colonial power had more than one policy. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Interpreting Zheng Chenggong: the Politics of Dramatizing

, - 'I ., . UN1VERSIlY OF HAWAII UBRARY 3~31 INTERPRETING ZHENG CHENGGONG: THE POLITICS OF DRAMATIZING A HISTORICAL FIGURE IN JAPAN, CHINA, AND TAIWAN (1700-1963) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEATRE AUGUST 2007 By Chong Wang Thesis Committee: Julie A. Iezzi, Chairperson Lurana D. O'Malley Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak · - ii .' --, L-' ~ J HAWN CB5 \ .H3 \ no. YI,\ © Copyright 2007 By Chong Wang We certity that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre. TIIESIS COMMITTEE Chairperson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to give my wannest thanks to my family for their strong support. I also want to give my since're thanks to Dr. Julie Iezzi for her careful guidance and tremendous patience during each stage of the writing process. Finally, I want to thank my proofreaders, Takenouchi Kaori and Vance McCoy, without whom this thesis could not have been completed. - . iv ABSTRACT Zheng Chenggong (1624 - 1662) was sired by Chinese merchant-pirate in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. A general at the end of the Chinese Ming Dynasty, he was a prominent leader of the movement opposing the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and in recovering Taiwan from Dutch colonial occupation in 1661. Honored as a hero in Japan, China, and Taiwan, he has been dramatized in many plays in various theatre forms in Japan (since about 1700), China (since 1906), and Taiwan (since the 1920s). -

Claes Gerritszoon Compaen

Claes Gerritszoon Compaen Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (Q8270). From Wikidata. Jump to navigation Jump to search. Privateer and pirate. Claas Compaan. Klaas Kompaan. edit. Also known as. English. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen. Privateer and pirate. Claas Compaan. Klaas Kompaan. Statements. instance of. human. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (1587, Oostzaan, North Holland - 25 February 1660, Oostzaan), also called Claas Compaan or Klaas Kompaan, was a 17th-century Dutch corsair and merchant. Dissatisfied as a privateer for the Dutch Republic, he later turned to piracy capturing hundreds of ships operating in Europe, the Mediterranean and West Africa during the 1620s. Born in Oostzaan, his father was an alleged member of the Geuzen of Dirck Duyvel housed in Zaanstreek allied other nobleman in opposition of Spanish Claes Gerritszoon Compaen was born in Oostzaan in 1587. He was a merchant who had some succes sailing along the coast of Guinea (on the Westcoast of Africa). The money he earned this way he used to equip his ship for privateering against the Spaniards, the pirates/privateers of Duinkerken and Oostende. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (died 1660AD - Privateer). Daniel Defoe (died 1731AD - Explorer). David Marteen (death Unknown - Pirate). Diego de Almagro (died 1538Ad - Explorer). Diego Velasquez de Cuellar (died 1524AD - Explorer). Dirk Chivers (death Unknown - Pirate). Dixie Bull (death Unknown - Pirate). Every Mac comes preinstalled with Gerritszoon.' But not Gerritszoon Display. That, you have to steal." â“Clay Jannon, Mr.â¦Â âœI chime in, â˜Yeah, he printed them using a brand-new typeface, made by a designer named Griffo Gerritszoon. It was awesome. Nobody has ever seen anything like it, and itâ™s still basically the most famous typeface ever. -

Shi Lang: Hero Or Villain? His Evolving Legacy in China and Taiwan

Ronald C. Po Shi Lang: hero or villain? His evolving legacy in China and Taiwan Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Po, Ronald C. (2017) Shi Lang: hero or villain? His evolving legacy in China and Taiwan. Modern Asian Studies . ISSN 0026-749X © 2017 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/81309/ Available in LSE Research Online: June 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Shi Lang: Hero or Villain? His Evolving Legacy in China and Taiwan Ronald C. Po London School of Economics [Accepted to be published in Modern Asian Studies (2018)] Abstract For over two centuries, some of China’s most prominent officials, literary figures, and intellectuals have paid special attention to the legacy of Shi Lang.