A STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O'hara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 Mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 7 mars 2020 Paris — Salle VV, Quartier Drouot 3, rue Rossini 75009 Paris — 16h30 — Expositions Publiques Vendredi 6 mars de 10h30 à 18h30 Samedi 7 mars de 10h30 à 15h00 — Intégralité des lots sur millon.com Département Experts Index Art Aborigène, Australie Catalogue ................................................................................. p. 4 Biographies ............................................................................. p. 56 Ordres d’achats ...................................................................... p. 64 Conditions de ventes ............................................................... p. 65 Liste des artistes Anonyme .................. n° 36, 95, 96, Nampitjinpa, Yuyuya .............. n° 89 Riley, Geraldine ..................n° 16, 24 .....................97, 98, 112, 114, 115, 116 Namundja, Bob .....................n° 117 Rontji, Glenice ...................... n° 136 Atjarral, Jacky ..........n° 101, 102, 104 Namundja, Glenn ........... n° 118, 127 Sandy, William ....n° 133, 141, 144, 147 Babui, Rosette ..................... n° 110 Nangala, Josephine Mc Donald ....... Sams, Dorothy ....................... n° 50 Badari, Graham ................... n° 126 ......................................n° 140, 142 Scobie, Margaret .................... n° 32 Bagot, Kathy .......................... n° 11 Tjakamarra, Dennis Nelson .... n° 132 Directrice Art Aborigène Baker, Maringka ................... -

Art Gallery of South Australia Major Achievements 2003

ANNUAL REPORT of the ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA for the year 1 July 2003 – 30 June 2004 The Hon. Mike Rann MP, Minister for the Arts Sir, I have the honour to present the sixty-second Annual Report of the Art Gallery Board of South Australia for the Gallery’s 123rd year, ended 30 June 2004. Michael Abbott QC, Chairman Art Gallery Board 2003–2004 Chairman Michael Abbott QC Members Mr Max Carter AO (until 18 January 2004) Mrs Susan Cocks (until 18 January 2004) Mr David McKee (until 20 July 2003) Mrs Candy Bennett (until 18 January 2004) Mr Richard Cohen (until 18 January 2004) Ms Virginia Hickey Mrs Sue Tweddell Mr Adam Wynn Mr. Philip Speakman (commenced 20 August 2003) Mr Andrew Gwinnett (commenced 19 January 2004) Mr Peter Ward (commenced 19 January 2004) Ms Louise LeCornu (commenced 19 January 2004) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Objectives 5 Major Achievements 2003-2004 6 Issues and Trends 9 Major Objectives 2004–2005 11 Resources and Administration 13 Collections 22 3 APPENDICES Appendix A Charter and Goals of the Art Gallery of South Australia 27 Appendix B1 Art Gallery Board 29 Appendix B2 Members of the Art Gallery of South Australia 29 Foundation Council and Friends of the Art Gallery of South Australia Committee Appendix B3 Art Gallery Organisational Chart 30 Appendix B4 Art Gallery Staff and Volunteers 31 Appendix C Staff Public Commitments 33 Appendix D Conservation 36 Appendix E Donors, Funds, Sponsorships 37 Appendix F Acquisitions 38 Appendix G Inward Loans 50 Appendix H Outward Loans 53 Appendix I Exhibitions and Public Programs 56 Appendix J Schools Support Services 61 Appendix K Gallery Guide Tour Services 61 Appendix L Gallery Publications 62 Appendix M Annual Attendances 63 Information Statement 64 Appendix N Financial Statements 65 4 PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES The Art Gallery of South Australia’s objectives and functions are effectively prescribed by the Art Gallery Act, 1939 and can be described as follows: • To collect heritage and contemporary works of art of aesthetic excellence and art historical or regional significance. -

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners Bond University would like to thank Dr Patrick Corrigan AM and the following companies for their generous contributions. Scholarship Partners Corporate Partners Supporting Partners Event Partners Gold Coast Professor Elizabeth Roberts Jingeri Thank you for you interest in supporting the valuable Indigenous scholarship program offered by Bond University. The University has a strong commitment to providing educational opportunities and a culturally safe environment for Indigenous students. Over the past several years the scholarship program has matured and our Indigenous student cohort and graduates have flourished. We are so proud of the students who have benefited from their scholarship and embarked upon successful careers in many different fields of work. The scholarship program is an integral factor behind these success stories. Our graduates are important role models in their communities and now we are seeing the next generation of young people coming through, following in the footsteps of the students before them. It is my honour and privilege to witness our young people receiving the gift of education, and I thank you for partnering with us to create change. Aunty Joyce Summers Bond University Fellow 3 Indigenous Gala Patron Dr Patrick Corrigan AM Dr Patrick Corrigan AM is one of Australia’s most prodigious art collectors and patrons. Since 2007, he has personally donated or provided on loan the outstanding ‘Corrigan’ collection on campus, which is Australia’s largest private collection of Indigenous art on public display. Dr Corrigan has been acknowledged with a Member of the Order of Australia (2000), Queensland Great medal (2014) and City of Gold Coast Keys to the City award (2015) for his outstanding contributions to the arts and philanthropy. -

Barbara Weir Barbara Weir Was Born About 1945 at Bundey River Station

Barbara Weir Barbara Weir was born about 1945 at Bundey River Station, a cattle station in the Utopia region (called Urupunta in the local Aboriginal language) of the Northern Territory. Her parents were Minnie Pwerle, an Aboriginal woman, and JacK Weir, a married Irish man. Under the anti-miscegenation racial laws of the time, their relationship was illegal, and the two were jailed. Jack Weir died not long after his release. Minnie Pwerle named their daughter Barbara Weir. Barbara was partly raised by Pwerle’s sister-in-law Emily Kngwarreye. (After age 80, Kngwarreye tooK up art and became one of Australia’s most prominent artists.) Barbara grew up in the area of Utopia until about age nine. One of the Stolen Generations, she was forcibly removed from her Aboriginal family by officials; the family believed she was later Killed. This was done under the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915, government or assigned officers were authorized in the territories to take half-caste children to be raised in British institutions to assimilate them to European culture. Some, liKe Barbara, were “fostered out”, and she grew up in a series of foster homes in Alice Springs, Victoria, and Darwin. Boys were usually prepared for manual jobs and girls for domestic service. In Darwin, at age 18 and worKing as a maid, Barbara Weir married Mervyn Torres. It was Torres who in 1963 or 1968, when passing through Alice Springs, asKed someone about Weir’s mother; he discovered that Minnie Pwerle was alive and living at Utopia. Mother and daughter were reunited but, although Weir regularly visited her family at Utopia, she did not form a close bond with her mother at first. -

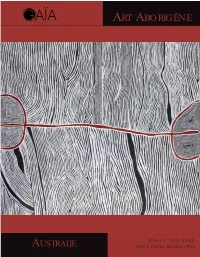

Art Aborigène

ART ABORIGÈNE LUNDI 1ER JUIN 2009 AUSTRALIE Vente à l’Atelier Richelieu - Paris ART ABORIGÈNE Atelier Richelieu - 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Vente le lundi 1er juin 2009 à 14h00 Commissaire-Priseur : Nathalie Mangeot GAÏA S.A.S. Maison de ventes aux enchères publiques 43, rue de Trévise - 75009 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 00 - Fax : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 01 E-mail : [email protected] - www.gaiaauction.com Exposition publique à l’Atelier Richelieu le samedi 30 mai de 14 h à 19 h le dimanche 31 mai de 10 h à 19 h et le lundi 1er juin de 10 h à 12 h 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Maison de ventes aux enchères Tous les lots sont visibles sur le site www.gaiaauction.com Expert : Marc Yvonnou 06 50 99 30 31 I GAÏAI 1er juin 2009 - 14hI 1 INDEX ABRÉVIATIONS utilisées pour les principaux musées australiens, océaniens, européens et américains : ANONYME 1, 2, 3 - AA&CC : Araluen Art & Cultural Centre (Alice Springs) BRITTEN, JACK 40 - AAM : Aboriginal Art Museum, (Utrecht, Pays Bas) CANN, CHURCHILL 39 - ACG : Auckland City art Gallery (Nouvelle Zélande) JAWALYI, HENRY WAMBINI 37, 41, 42 - AIATSIS : Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres JOOLAMA, PADDY CARLTON 46 Strait Islander Studies (Canberra) JOONGOORRA, HECTOR JANDANY 38 - AGNSW : Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) JOONGOORRA, BILLY THOMAS 67 - AGSA : Art Gallery of South Australia (Canberra) KAREDADA, LILY 43 - AGWA : Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth) KEMARRE, ABIE LOY 15 - BM : British Museum (Londres) LYNCH, J. 4 - CCG : Campbelltown City art Gallery, (Adelaïde) -

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE Samedi 4 Juin 2016 Paris Paris Juin 2016 4 Samedi AUSTRALIE ART ABORIGÈNE, ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE

Paris 2016 Samedi 4 juin ART ABORIGÈNE, ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE ABORIGÈNE, ART AUSTRALIE Samedi 4 juin 2016 Paris ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE Hôtel Drouot, Salle 11 Samedi 4 juin 2016 15h Expositions publiques Vendredi 3 juin de 11h à 18h Samedi 4 juin de 11h à 13h30 En partenariat avec Intégralité des lots sur millon.com MILLON 1 Art Aborigène, Australie Index Catalogue . p 4 Biographies . p 58 Conditions de ventes . p 63 Ordres d’achats . p 64 Liste des artistes AN GUNGUNA Jimmy n° 53 NAWILIL Jack n° 58 BAKER Maringka n° 87 NELSON Annie n° 52 BROWN Nyuju Stumpy n° 80, 81 NGALAKURN Jimmy n° 55 COOK Ian n° 57 NGALE Angelina (Pwerle) n° 65 DIXON Harry n° 56 NUNGALA Julie Robinson n° 99 DORRUNG Micky n° 34, 35 NUNGURRAYI Elizabeth Nyumi n° 10 JAGAMARRA Michael Nelson n° 100, 102 PETYARRE Anna Price n° 30 JAPANGARDI Michael Tommy n° 25 PETYARRE Gloria n° 1, 2, 3, 31, 40, 101 Marc Yvonnou Nathalie Mangeot JUGADAI Daisy n° 14 PETYARRE Kathleen n° 4, 37, 41, 42, 43 KEMARRE Abie Loy n° 7, 93 PETYARRE Violet n° 6 KNGWARREYE Emily Kame n° 64 PWERLE Minnie n° 62, 63 LUDJARRA Phillip Morris n° 36 RILEY Alison Munti n° 24 MARAMBARA Jack n° 60, 61 STEVENS Anyupa n° 13 NAKAMARRA Bessie Sims n° 97, 98 THOMAS Madigan n° 49 NAMPINJIMPA Maureen Hudson n° 23 TIMMS Freddy (Freddie) n° 46, 47, 48 NAMPITJINPA Tjawina Porter n° 28 TJAMPITJINPA Ronnie n° 32, 38, 45, 84 NANGALA Julie Robertson n° 5, 22 TJAPALTJARRI « Dr » George Takata n° 29 NANGALA Yinarupa n° 20 TJAPALTJARRI Mick Namarari n° 21 NAPALTJARRI Linda Syddick n° 11, 17, 74 TJAPALTJARRI Paddy Sims n° -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

Auction - Aboriginal Art Auction - Noosa Springs QLD 16/06/2019 1:00 PM AEST

Auction - Aboriginal Art Auction - Noosa Springs QLD 16/06/2019 1:00 PM AEST Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 1 WALALA TJAPALTJARRI "Tingari" Acrylic on linen. Painted in 2018. 12 LUCKY MORTON KNGWARREYE "My Country Acrylic on canvas. Come with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is stretched and ready to Painted in 2017. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is hang. 56cm x 62cm stretched and ready to hang. 90cm x 91cm WALALA TJAPALTJARRI"Tingari"Acrylic on linen.Painted in LUCKY MORTON KNGWARREYE"My CountryAcrylic on 2018.Come with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is stretched and canvas.Painted in 2017.Comes with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is ready to hang.56cm x 62cm stretched and ready to hang.90cm x 91cm Est. 400 - 600 Est. 500 - 1,000 2 KATRINA BUBUNTJA "Bush Seeds & Flowers" Acrylic on canvas. 13 EDWARD BLITNER TAIITA "Mimi Spirits & Barrumundi" Acrylic on Painted in 2017. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is linen. Painted for Desert Art Gallery. Comes with Certificate of stretched and ready to hang. 59cm x 71cm Authenticity. Artwork is stretched and ready to hang. 58cm x 88cm KATRINA BUBUNTJA"Bush Seeds & Flowers"Acrylic on DAG-19857 canvas.Painted in 2017.Comes with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is EDWARD BLITNER TAIITA"Mimi Spirits & Barrumundi"Acrylic on stretched and ready to hang.59cm x 71cm linen.Painted for Desert Art Gallery.Comes with Certificate of Est. 500 - 800 Authenticity.Artwork is stretched and ready to hang.58cm x 3 LILY KELLY NAPANGARDI "Tali - Sand Hills" Acrylic on canvas. 88cmDAG-19857 Painted in 2018. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. -

Urban Representations: Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics

Urban Representations: Cultural expression, identity and politics Urban Representations: Cultural expression, identity and politics Edited by Sylvia Kleinert and Grace Koch Developed from papers presented in the Representation and Cultural Expression stream at the 2009 AIATSIS National Indigenous Studies Conference ‘Perspectives on Urban Life: Connections and reconnections’ First published in 2012 by AIATSIS Research Publications © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2012 © in individual chapters is held by the authors, 2012 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this publication, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4285 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Urban representations [electronic resource] : cultural expression, identity, and politics : developed from papers presented in the Representation Stream at the AIATSIS 2009 National Indigenous Studies Conference ‘Perceptions of Urban Life : Connections and Reconnections’ / edited by Sylvia Kleinert and Grace Koch. -

46 X 38 Cm Ethnie Pintupi – Kiwirrkurra

Miriam Napanangka (1946 - ) Sans titre, 1999 1 200 / 300 € Acrylique sur toile - 46 x 38 cm Ethnie Pintupi – Kiwirrkurra – Désert Occidental Nancy Nungurrayi (c. 1935 - 2010) Sans titre, 1999 2 300 / 400 € Acrylique sur toile - 45 x 40 cm Groupe Pintupi - Désert Occidental - Kintore Tatali Napurrula (c. 1943 - ) Sans titre, 1999 3 200 / 300 € Acrylique sur toile - 46 x 38 cm Groupe Pintupi / Luritja –– Kintore - Désert Occidental Nancy Nungurrayi (c. 1935 - 2010) Sans titre, 1999 Acrylique sur toile - 46 x 38 cm Groupe Pintupi – Désert Central – Kintore 4 400 / 600 € Cette toile nous offre un bel aperçu de la production des femmes de cette région avec des motifs à plusieurs niveaux de lecture. A la fois elle décrit une cérémonie de femmes et dans un niveau supérieur, décrit les actions des Ancêtres du Temps du Rêve. Nanyuma Napangati (c. 1943 - ) Sans titre, 1998 5 200 / 250 € Acrylique sur toile - 60 x 30 cm Groupe Pintupi – Désert Occidental Tjunkiya Napaltjarri (c. 1928 - 2009) Sans titre, 1998 6 200 / 250 € Acrylique sur toile - 60 x 30 cm Ethnie Pintupi – Désert Central – Kintore / Kiwirrkura Tjunkiya Napaltjarri (1928 - 2009 ) Sans titre, 1999 Acrylique sur toile - 91 x 60 cm 7 Groupe Pintupi – Désert Central – Kintore / Kiwirrkura 1500 / 2000 € Cette toile de très bonne facture décrit la collecte de baies par les femmes sur le site d’Umari. Bertha Kaline "Lamanpunta", 1997 Acrylique sur toile - 91,5 x 61,5 cm 8 800 / 1000 € Communauté de Balgo - Kimberley - Australie Occidentale Le site de Lamanpunta est situé dans le Great Sandy Desert. John John Bennett Tjapangati (1937 - 2002) Sans titre, 1997 Acrylique sur toile - 92 x 61 cm 9 Groupe Pintupi - Kintore - Désert Occidental 1000 / 1500 € John John s'inspire ici des très secrets et sacrés Cycles Tingari, décrivant le voyage des Ancêtres qui portent ce nom. -

Page 1 Charleston’S Fine Killara Aboriginal Art Auction Sunday, August Art Auctions 28, 2016

Charleston’s Fine Killara Aboriginal Art Auction Sunday, August Art Auctions 28, 2016 Lot No Item 1 Sacha Long Pitjara acrylic on linen, Bush Yam Dreaming 2009, size 56 x 41cm 2 Judy Greeny Kngwarreye acrylic on linen, Yam Dreaming 2009, size 56 x 41cm 3 Galya Pwerle acrylic on linen, Awelye Atnwengerrp 2008, size 70 x 55cm 4 Jeannie Pitjara acrylic on canvas, Yam Roots 2015, size 150 x 50cm 5 Sharon Hayes Peltharre acrylic on canvas 2011, size 150 x 70cm 6 Galya Pwerle acrylic on linen, Awelye Atnwengerrp 2008, size 120 x 90cm 7 Jeannie Petyarre acrylic on canvas, Bush Medicine 2015, size 148 x 90cm 8 Lisa Mills Pwerl acrylic on canvas, Bush Yam 2014, size 145 x 83cm 9 Sonia Daniels Nakamarra acrylic on canvas 2016, size 124 x 102cm 10 Mary Pitjara acrylic on canvas 2015, size 200 x 80cm 11 Nancy Nungurrayi acrylic on canvas 2008, size 122 x 91cm 12 Lily Kelly Napangardi acrylic on canvas, Tali 2016, size 150 x 90cm 13 Gloria Tamerre Petyarre acrylic on linen, Leaves 2008, size 123 x 120cm 14 Rover Thomas decorative print of the original, Two Men Dreaming 15 Colleen Wallace Nungarrayi acrylic on linen, Annamura Country 2009, size 56 x 41cm 16 Betty Mbitjana acrylic on canvas, Body Paint 2016, size 150 x 90cm 17 Marcia Turner Petyarre acrylic on linen, Body Paint 2009, size 56 x 41cm 18 Tjuruparu Watson acrylic on canvas, Kapi Piti 2007, size 167 x 128cm 19 Kenny Williams Tjampitjinpa acrylic on canvas 2005, size 122 x 91cm 20 Anna Pitjara acrylic on canvas, My Country 2016, size 200 x 120cm 21 Narpula Scobie Napurrula acrylic on linen, -

Aboriginal Art Galleries

ABORIGINAL ART GALLERIES BARBARA WEIR Barbara is one of Aboriginal Australia’s stolen generations. These were people who were forcibly taken from their parents as children and sent to other parts of the country to be raised in European families. This policy was pursued from the early 1900’s to the 1970’s, as part of the Australian government policy to integrate mixed race children from fringe settlements into mainstream Australian life. Barbara’s mother is Aboriginal artist Minnie Pwerle and her father, Irish-American Jack Weir, a married station owner in the Northern Territory. Barbara’s career as an artist was inspired by the dynamic community of artists at Utopia and the work of her adopted grandmother Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Emily’s work had a profound impact on her and in the early 1990’s she began seriously to explore her artistic talents. Highly experimental in her approach, she tried many mediums and in 1994 went to Indonesia with other artists to explore the art of batik. This gave her new insights into her own process and she returned full of ideas on how to develop her own style. Initially her painting was largely figurative using traditional symbols such as circles, ‘u’ shapes, wavy lines and dotting to indicate her traditional Dreamtime story. Since then it has evolved to abstraction, a much more expressive and flexible form. Bush Berry, Grass Seed, Wild Flower and My Mother’s Country are her Dreamings. These are all associated with women’s ceremony (they refer to women’s body decoration for ceremony and the activity of food gathering of local seeds, grasses, berries, potato, plum, banana, flowers and yams).