Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 Mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 7 mars 2020 Paris — Salle VV, Quartier Drouot 3, rue Rossini 75009 Paris — 16h30 — Expositions Publiques Vendredi 6 mars de 10h30 à 18h30 Samedi 7 mars de 10h30 à 15h00 — Intégralité des lots sur millon.com Département Experts Index Art Aborigène, Australie Catalogue ................................................................................. p. 4 Biographies ............................................................................. p. 56 Ordres d’achats ...................................................................... p. 64 Conditions de ventes ............................................................... p. 65 Liste des artistes Anonyme .................. n° 36, 95, 96, Nampitjinpa, Yuyuya .............. n° 89 Riley, Geraldine ..................n° 16, 24 .....................97, 98, 112, 114, 115, 116 Namundja, Bob .....................n° 117 Rontji, Glenice ...................... n° 136 Atjarral, Jacky ..........n° 101, 102, 104 Namundja, Glenn ........... n° 118, 127 Sandy, William ....n° 133, 141, 144, 147 Babui, Rosette ..................... n° 110 Nangala, Josephine Mc Donald ....... Sams, Dorothy ....................... n° 50 Badari, Graham ................... n° 126 ......................................n° 140, 142 Scobie, Margaret .................... n° 32 Bagot, Kathy .......................... n° 11 Tjakamarra, Dennis Nelson .... n° 132 Directrice Art Aborigène Baker, Maringka ................... -

Appendix a (PDF 85KB)

A Appendix A: Committee visits to remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities As part of the Committee’s inquiry into remote Indigenous community stores the Committee visited seventeen communities, all of which had a distinctive culture, history and identity. The Committee began its community visits on 30 March 2009 travelling to the Torres Strait and the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland over four days. In late April the Committee visited communities in Central Australia over a three day period. Final consultations were held in Broome, Darwin and various remote regions in the Northern Territory including North West Arnhem Land. These visits took place in July over a five day period. At each location the Committee held a public meeting followed by an open forum. These meetings demonstrated to the Committee the importance of the store in remote community life. The Committee appreciated the generous hospitality and evidence provided to the Committee by traditional owners and elders, clans and families in all the remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities visited during the inquiry. The Committee would also like to thank everyone who assisted with the administrative organisation of the Committee’s community visits including ICC managers, Torres Strait Councils, Government Business Managers and many others within the communities. A brief synopsis of each community visit is set out below.1 1 Where population figures are given, these are taken from a range of sources including 2006 Census data and Grants Commission figures. 158 EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS Torres Strait Islands The Torres Strait Islands (TSI), traditionally called Zenadth Kes, comprise 274 small islands in an area of 48 000 square kilometres (kms), from the tip of Cape York north to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. -

Art Gallery of South Australia Major Achievements 2003

ANNUAL REPORT of the ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA for the year 1 July 2003 – 30 June 2004 The Hon. Mike Rann MP, Minister for the Arts Sir, I have the honour to present the sixty-second Annual Report of the Art Gallery Board of South Australia for the Gallery’s 123rd year, ended 30 June 2004. Michael Abbott QC, Chairman Art Gallery Board 2003–2004 Chairman Michael Abbott QC Members Mr Max Carter AO (until 18 January 2004) Mrs Susan Cocks (until 18 January 2004) Mr David McKee (until 20 July 2003) Mrs Candy Bennett (until 18 January 2004) Mr Richard Cohen (until 18 January 2004) Ms Virginia Hickey Mrs Sue Tweddell Mr Adam Wynn Mr. Philip Speakman (commenced 20 August 2003) Mr Andrew Gwinnett (commenced 19 January 2004) Mr Peter Ward (commenced 19 January 2004) Ms Louise LeCornu (commenced 19 January 2004) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal Objectives 5 Major Achievements 2003-2004 6 Issues and Trends 9 Major Objectives 2004–2005 11 Resources and Administration 13 Collections 22 3 APPENDICES Appendix A Charter and Goals of the Art Gallery of South Australia 27 Appendix B1 Art Gallery Board 29 Appendix B2 Members of the Art Gallery of South Australia 29 Foundation Council and Friends of the Art Gallery of South Australia Committee Appendix B3 Art Gallery Organisational Chart 30 Appendix B4 Art Gallery Staff and Volunteers 31 Appendix C Staff Public Commitments 33 Appendix D Conservation 36 Appendix E Donors, Funds, Sponsorships 37 Appendix F Acquisitions 38 Appendix G Inward Loans 50 Appendix H Outward Loans 53 Appendix I Exhibitions and Public Programs 56 Appendix J Schools Support Services 61 Appendix K Gallery Guide Tour Services 61 Appendix L Gallery Publications 62 Appendix M Annual Attendances 63 Information Statement 64 Appendix N Financial Statements 65 4 PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES The Art Gallery of South Australia’s objectives and functions are effectively prescribed by the Art Gallery Act, 1939 and can be described as follows: • To collect heritage and contemporary works of art of aesthetic excellence and art historical or regional significance. -

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners

Bond University Indigenous Gala Friday 16 November, 2018 Bond University Indigenous Program Partners Bond University would like to thank Dr Patrick Corrigan AM and the following companies for their generous contributions. Scholarship Partners Corporate Partners Supporting Partners Event Partners Gold Coast Professor Elizabeth Roberts Jingeri Thank you for you interest in supporting the valuable Indigenous scholarship program offered by Bond University. The University has a strong commitment to providing educational opportunities and a culturally safe environment for Indigenous students. Over the past several years the scholarship program has matured and our Indigenous student cohort and graduates have flourished. We are so proud of the students who have benefited from their scholarship and embarked upon successful careers in many different fields of work. The scholarship program is an integral factor behind these success stories. Our graduates are important role models in their communities and now we are seeing the next generation of young people coming through, following in the footsteps of the students before them. It is my honour and privilege to witness our young people receiving the gift of education, and I thank you for partnering with us to create change. Aunty Joyce Summers Bond University Fellow 3 Indigenous Gala Patron Dr Patrick Corrigan AM Dr Patrick Corrigan AM is one of Australia’s most prodigious art collectors and patrons. Since 2007, he has personally donated or provided on loan the outstanding ‘Corrigan’ collection on campus, which is Australia’s largest private collection of Indigenous art on public display. Dr Corrigan has been acknowledged with a Member of the Order of Australia (2000), Queensland Great medal (2014) and City of Gold Coast Keys to the City award (2015) for his outstanding contributions to the arts and philanthropy. -

Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health

The International Indigenous Policy Journal Volume 3 Article 6 Issue 3 Water and Indigenous Peoples September 2012 Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia Heather Browett Flinders University, [email protected] Meryl Pearce Flinders University, [email protected] Eileen M. Willis Flinders University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Browett, H. , Pearce, M. , Willis, E. M. (2012). Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia. Th e International Indigenous Policy Journal, 3(3) . DOI: 10.18584/iipj.2012.3.3.6 Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia Abstract The provision of services such as power, water, and housing for Indigenous people is seen as essential in the Australian Government’s "Closing the Gap" policy. While the cost of providing these services, in particular adequate water supplies, is significantly higher in remote areas, they are key contributors to improving the health of Indigenous peoples. In many remote areas, poor quality groundwater is the only supply available. Hard water results in the deterioration of health hardware, which refers to the facilities considered essential for maintaining health. This study examined the costs associated with water hardness in eight communities in the Northern Territory. Results show a correlation between water hardness and the cost of maintaining health hardware, and illustrates one aspect of additional resourcing required to maintain Indigenous health in remote locations. Keywords Indigneous, water, health hardware, hard water Acknowledgments Thanks are extended to Power and Water, Northern Territory for funding this project. -

Incite Arts 2018 Annual Report

INCITE ARTS 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Incite Arts: Delivering community arts and culture programs in the central desert region since 1998 1 1. About Us We at Incite Arts acknowledge our work is undertaken on the land of the Arrernte people, the traditional owners of Mparntwe. We give our respect to the Arrernte people, their culture and to the Elders, past, present and future. We are committed to working together with the Arrernte people to care for this land for our shared future. Established in 1998, Incite Arts is Central Australia’s own community-led arts company working with young people, people with disability, Aboriginal communities and other diverse communities in Alice Springs and the central desert region. Incite Arts focuses on ‘connecting people and place’ throughout all programs. Incite Arts - Responds to community needs and aspirations - Expresses and celebrates cultural identity - Designs and delivers targeted arts programs - Collaborates and builds strong community partnerships Incite is nationally recognised as the premier community arts company in central Australia sharing our unique stories on the world stage. Positioned as the key facilitator of community arts in Central Australia, Incite has built strong trust and enduring community partnerships, since 1998, and is a significant contributor to community capacity building through participation in the Arts. Since 2004, Incite Arts has championed the development of arts and disability practice in the region. Incite uniquely drives innovation through community arts practice to create astonishing art and benchmark new levels of access and inclusion in the region. Incite is nationally recognised for innovation, quality and ethical work processes with communities. -

Barbara Weir Barbara Weir Was Born About 1945 at Bundey River Station

Barbara Weir Barbara Weir was born about 1945 at Bundey River Station, a cattle station in the Utopia region (called Urupunta in the local Aboriginal language) of the Northern Territory. Her parents were Minnie Pwerle, an Aboriginal woman, and JacK Weir, a married Irish man. Under the anti-miscegenation racial laws of the time, their relationship was illegal, and the two were jailed. Jack Weir died not long after his release. Minnie Pwerle named their daughter Barbara Weir. Barbara was partly raised by Pwerle’s sister-in-law Emily Kngwarreye. (After age 80, Kngwarreye tooK up art and became one of Australia’s most prominent artists.) Barbara grew up in the area of Utopia until about age nine. One of the Stolen Generations, she was forcibly removed from her Aboriginal family by officials; the family believed she was later Killed. This was done under the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915, government or assigned officers were authorized in the territories to take half-caste children to be raised in British institutions to assimilate them to European culture. Some, liKe Barbara, were “fostered out”, and she grew up in a series of foster homes in Alice Springs, Victoria, and Darwin. Boys were usually prepared for manual jobs and girls for domestic service. In Darwin, at age 18 and worKing as a maid, Barbara Weir married Mervyn Torres. It was Torres who in 1963 or 1968, when passing through Alice Springs, asKed someone about Weir’s mother; he discovered that Minnie Pwerle was alive and living at Utopia. Mother and daughter were reunited but, although Weir regularly visited her family at Utopia, she did not form a close bond with her mother at first. -

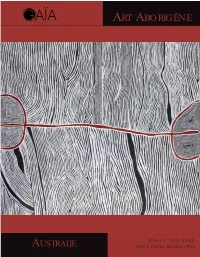

Art Aborigène

ART ABORIGÈNE LUNDI 1ER JUIN 2009 AUSTRALIE Vente à l’Atelier Richelieu - Paris ART ABORIGÈNE Atelier Richelieu - 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Vente le lundi 1er juin 2009 à 14h00 Commissaire-Priseur : Nathalie Mangeot GAÏA S.A.S. Maison de ventes aux enchères publiques 43, rue de Trévise - 75009 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 00 - Fax : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 01 E-mail : [email protected] - www.gaiaauction.com Exposition publique à l’Atelier Richelieu le samedi 30 mai de 14 h à 19 h le dimanche 31 mai de 10 h à 19 h et le lundi 1er juin de 10 h à 12 h 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Maison de ventes aux enchères Tous les lots sont visibles sur le site www.gaiaauction.com Expert : Marc Yvonnou 06 50 99 30 31 I GAÏAI 1er juin 2009 - 14hI 1 INDEX ABRÉVIATIONS utilisées pour les principaux musées australiens, océaniens, européens et américains : ANONYME 1, 2, 3 - AA&CC : Araluen Art & Cultural Centre (Alice Springs) BRITTEN, JACK 40 - AAM : Aboriginal Art Museum, (Utrecht, Pays Bas) CANN, CHURCHILL 39 - ACG : Auckland City art Gallery (Nouvelle Zélande) JAWALYI, HENRY WAMBINI 37, 41, 42 - AIATSIS : Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres JOOLAMA, PADDY CARLTON 46 Strait Islander Studies (Canberra) JOONGOORRA, HECTOR JANDANY 38 - AGNSW : Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) JOONGOORRA, BILLY THOMAS 67 - AGSA : Art Gallery of South Australia (Canberra) KAREDADA, LILY 43 - AGWA : Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth) KEMARRE, ABIE LOY 15 - BM : British Museum (Londres) LYNCH, J. 4 - CCG : Campbelltown City art Gallery, (Adelaïde) -

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE Samedi 4 Juin 2016 Paris Paris Juin 2016 4 Samedi AUSTRALIE ART ABORIGÈNE, ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE

Paris 2016 Samedi 4 juin ART ABORIGÈNE, ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE ABORIGÈNE, ART AUSTRALIE Samedi 4 juin 2016 Paris ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE Hôtel Drouot, Salle 11 Samedi 4 juin 2016 15h Expositions publiques Vendredi 3 juin de 11h à 18h Samedi 4 juin de 11h à 13h30 En partenariat avec Intégralité des lots sur millon.com MILLON 1 Art Aborigène, Australie Index Catalogue . p 4 Biographies . p 58 Conditions de ventes . p 63 Ordres d’achats . p 64 Liste des artistes AN GUNGUNA Jimmy n° 53 NAWILIL Jack n° 58 BAKER Maringka n° 87 NELSON Annie n° 52 BROWN Nyuju Stumpy n° 80, 81 NGALAKURN Jimmy n° 55 COOK Ian n° 57 NGALE Angelina (Pwerle) n° 65 DIXON Harry n° 56 NUNGALA Julie Robinson n° 99 DORRUNG Micky n° 34, 35 NUNGURRAYI Elizabeth Nyumi n° 10 JAGAMARRA Michael Nelson n° 100, 102 PETYARRE Anna Price n° 30 JAPANGARDI Michael Tommy n° 25 PETYARRE Gloria n° 1, 2, 3, 31, 40, 101 Marc Yvonnou Nathalie Mangeot JUGADAI Daisy n° 14 PETYARRE Kathleen n° 4, 37, 41, 42, 43 KEMARRE Abie Loy n° 7, 93 PETYARRE Violet n° 6 KNGWARREYE Emily Kame n° 64 PWERLE Minnie n° 62, 63 LUDJARRA Phillip Morris n° 36 RILEY Alison Munti n° 24 MARAMBARA Jack n° 60, 61 STEVENS Anyupa n° 13 NAKAMARRA Bessie Sims n° 97, 98 THOMAS Madigan n° 49 NAMPINJIMPA Maureen Hudson n° 23 TIMMS Freddy (Freddie) n° 46, 47, 48 NAMPITJINPA Tjawina Porter n° 28 TJAMPITJINPA Ronnie n° 32, 38, 45, 84 NANGALA Julie Robertson n° 5, 22 TJAPALTJARRI « Dr » George Takata n° 29 NANGALA Yinarupa n° 20 TJAPALTJARRI Mick Namarari n° 21 NAPALTJARRI Linda Syddick n° 11, 17, 74 TJAPALTJARRI Paddy Sims n° -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

Auction - Aboriginal Art Auction - Noosa Springs QLD 16/06/2019 1:00 PM AEST

Auction - Aboriginal Art Auction - Noosa Springs QLD 16/06/2019 1:00 PM AEST Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 1 WALALA TJAPALTJARRI "Tingari" Acrylic on linen. Painted in 2018. 12 LUCKY MORTON KNGWARREYE "My Country Acrylic on canvas. Come with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is stretched and ready to Painted in 2017. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is hang. 56cm x 62cm stretched and ready to hang. 90cm x 91cm WALALA TJAPALTJARRI"Tingari"Acrylic on linen.Painted in LUCKY MORTON KNGWARREYE"My CountryAcrylic on 2018.Come with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is stretched and canvas.Painted in 2017.Comes with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is ready to hang.56cm x 62cm stretched and ready to hang.90cm x 91cm Est. 400 - 600 Est. 500 - 1,000 2 KATRINA BUBUNTJA "Bush Seeds & Flowers" Acrylic on canvas. 13 EDWARD BLITNER TAIITA "Mimi Spirits & Barrumundi" Acrylic on Painted in 2017. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. Artwork is linen. Painted for Desert Art Gallery. Comes with Certificate of stretched and ready to hang. 59cm x 71cm Authenticity. Artwork is stretched and ready to hang. 58cm x 88cm KATRINA BUBUNTJA"Bush Seeds & Flowers"Acrylic on DAG-19857 canvas.Painted in 2017.Comes with Certificate of Authenticity.Artwork is EDWARD BLITNER TAIITA"Mimi Spirits & Barrumundi"Acrylic on stretched and ready to hang.59cm x 71cm linen.Painted for Desert Art Gallery.Comes with Certificate of Est. 500 - 800 Authenticity.Artwork is stretched and ready to hang.58cm x 3 LILY KELLY NAPANGARDI "Tali - Sand Hills" Acrylic on canvas. 88cmDAG-19857 Painted in 2018. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. -

Urban Representations: Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics

Urban Representations: Cultural expression, identity and politics Urban Representations: Cultural expression, identity and politics Edited by Sylvia Kleinert and Grace Koch Developed from papers presented in the Representation and Cultural Expression stream at the 2009 AIATSIS National Indigenous Studies Conference ‘Perspectives on Urban Life: Connections and reconnections’ First published in 2012 by AIATSIS Research Publications © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2012 © in individual chapters is held by the authors, 2012 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act), no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Act also allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this publication, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied or distributed digitally by any educational institution for its educational purposes, provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1111 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4285 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Urban representations [electronic resource] : cultural expression, identity, and politics : developed from papers presented in the Representation Stream at the AIATSIS 2009 National Indigenous Studies Conference ‘Perceptions of Urban Life : Connections and Reconnections’ / edited by Sylvia Kleinert and Grace Koch.