Geomorphology of the Navajo Country W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMNP Mountains Manual 2017

Mountain Adventures Manual utahmasternaturalist.org June 2017 UMN/Manual/2017-03pr Welcome to Utah Master Naturalist! Utah Master Naturalist was developed to help you initiate or continue your own personal journey to increase your understanding of, and appreciation for, Utah’s amazing natural world. We will explore and learn aBout the major ecosystems of Utah, the plant and animal communities that depend upon those systems, and our role in shaping our past, in determining our future, and as stewards of the land. Utah Master Naturalist is a certification program developed By Utah State University Extension with the partnership of more than 25 other organizations in Utah. The mission of Utah Master Naturalist is to develop well-informed volunteers and professionals who provide education, outreach, and service promoting stewardship of natural resources within their communities. Our goal, then, is to assist you in assisting others to develop a greater appreciation and respect for Utah’s Beautiful natural world. “When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” - Aldo Leopold Participating in a Utah Master Naturalist course provides each of us opportunities to learn not only from the instructors and guest speaKers, But also from each other. We each arrive at a Utah Master Naturalist course with our own rich collection of knowledge and experiences, and we have a unique opportunity to share that Knowledge with each other. This helps us learn and grow not just as individuals, but together as a group with the understanding that there is always more to learn, and more to share. -

Canyon's 'Guardians' Press for Protections by Matthew Putesoy - Jul

THE ARIZONA REPUBLIC Canyon's 'guardians' press for protections by Matthew Putesoy - Jul. 25, 2009 My Turn The Grand Canyon is a national treasure, inviting 5 million people every year to explore and be inspired by its beauty. To the Havasuw 'Baaja, who have lived in the region for many hundreds of years, it is sacred. As the "guardians of the Grand Canyon," we strenuously object to mining for uranium here. It is a threat to the health of our environment and tribe, our tourism-based economy, and our religion. Thank you, Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar, for announcing a two-year moratorium on new mining claims in the 1 million acres of lands around Grand Canyon National Park. But existing claims, such as those pursued by Canadian-based Denison Mines Corp., still threaten the animals, air, drinking water and people of this region. Denison, which has staked 110 claims around the Grand Canyon, is seeking groundwater-aquifer permits that would allow it to reopen the Canyon Mine, near Red Butte on the South Rim, as well as two other mining sites. Uranium mining has been associated with contamination of ground or surface water. Here, mining could poison the aquifer, which extends for 5,000 square miles under the Coconino Plateau, and serves as drinking water for our tribe and neighboring communities. As I told Congress recently, if our water were polluted, we could not relocate to Phoenix or someplace else and still survive as the Havasupai Tribe. We are the Grand Canyon. Thanks to Arizona Congressman Raul Grijalva for introducing the Grand Canyon Watersheds Protection Act. -

2016 Arizona Shade Tree Planting Prioritization ATLAS

2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization 1 Urban and Community Forestry 2016 Arizona Shade Tree Planting Prioritization ATLAS Planning Maps for the Department of Forestry and Fire Management 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization Atlas About the 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization Atlas This collection of maps summarizes the results of the 2016 Shade Tree Planting Prioritization analysis of the Urban and Community Forestry Program (UCF) at the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management (DFFM). The purpose of the analysis was to assess existing urban forests in Arizona’s communities and identify shade tree planting needs. The spatial analysis, based on U.S. Census Block Group polygons, generated seven sub-indices for criteria identified by an expert panel: population density, lack of canopy cover, low-income, traffic proximity, sustainability, air quality, and urban heat effect. The seven sub-indices were combined into one Shade Tree Planting Priority Index and further summarized into a Shade Tree Planting Priority Ranking. The resulting reports, maps, and GIS data provide compiled information that can be easily used for identifying areas for strategic shade tree planting within a community or across Arizona’s major cities and towns. These maps provide limited detail for conveying the scale and depth of the analysis results which – for more detailed use – are best explored through the analysis report, interactive maps, and the GIS data available through the UCF Program webpage at https://forestryandfire.az.gov/forestry-community-forestry/urban-community-forestry/projects. Note: At the time of publication, two known analysis area errors have been identified. A few of Safford’s incorporated easements were not captured correctly. -

Hydrogeology of the Chinle Wash Watershed, Navajo Nation Arizona, Utah and New Mexico

Hydrogeology of the Chinle Wash Watershed, Navajo Nation Arizona, Utah and New Mexico Item Type Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); text Authors Roessel, Raymond J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:50:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/191379 HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE CHINLE WASH WATERSHED, NAVAJO NATION, ARIZONA, UTAH AND NEW MEXICO by Raymond J. Roessel A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HYDROLOGY AND WATER RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN HYDROLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1994 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

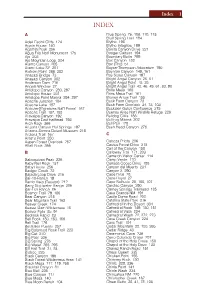

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

"Erosion,' Surfaces Of" ' '" '"

· . ,'.' . .' . ' :' ~ . DE L'INSTITUTNATIONAL ' /PQi[JRJl.'El'UDJiAC;RO,NU1VII,QlUE, DU CONGO BELGE , , (I. N. E.A: C.) "EROSION,' SURFACES OF" ' '" '""",,,U ,,"GENTRALAFRICANINTERIOR' ,HIGH PLATEAUS" 'T.OCICAL SURVEYS ,BY Robert V. RUHE Geomorphologist ECA ' INEAC Soil Mission Belgian Congo. , SERIE SCIENTIFIQUE N° 59 1954 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 11111' IIII II IIIJ '11 III If II I 78 0207537 9 EROSION SURF ACES OF CENTRAL AFRICAN INTERIOR HIGH PLATEAUS I PUBLICATIONS DE L'INSTITUT NATIONAL POUR L'ETUDE AGRONOMIQUE DU CONGO BELGE I I (1. N. E.A. C.) ! I EROSION SURFACES OF CENTRAL AFRICAN INTERIOR HIGH PLATEAUS BY Robert V. RUHE Gcomorphologist ECA ' INEAC Soil Mission Belgian Congo. Ij SERIE SCIENTIFIQUE N° 59 1954 CONTENTS Abstract 7 'Introduction 9 Previous work. 12 Geographic Distribution of Major Erosion Surfaces 12 Ages of the Major Erosion Surfaces 16 Tertiary Erosion Surfaces of the Ituri, Belgian Congo 18 Post-Tertiary Erosion Surfaces of the Ituri, Belgian Congo 26 Relations of the Erosion Surfaces of the Ituri Plateaus and the Congo Basin 33 Bibliography 37 ILLUSTRATIONS FIG. 1. Region of reconnaissance studies. 10 FIG. 2. Areas of detailed and semi-detailed studies. 11 FIG. 3. Classification of erosion surfaces by LEPERsONNE and DE HEINZELlN. 14 FIG. 4. Area-altitude distribution curves of erosion surfaces of Loluda Watershed. 27 FIG. 5. Interfluve summit profiles and adjacent longitudinal stream profiles in Loluda Watershed . 29 FIG. 6. Composite longitudinal stream profile in Loluda Watershed. 30 FIG. 7. Diagrammatic explanation of cutting of Quaternary surfaces- complex (Bunia-Irumu Plain) . 34 PLATES I Profiles of end-Tertiary erosion surface. -

Tse' Nikani Draft Corridor Management

Tse'nikani Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan DRAFT August 2013 Introduction Purpose Tse’nikani Scenic Byway was established The purpose of a byway corridor as an Arizona Byway in 2005 and given the management plan is not to create more name Tse’nikani ‘Flat Mesa Rock’ Scenic regulations or taxes. Rather, a corridor Byway. management plan documents the goals, strategies, and responsibilities for preserving and enhancing the byway’s most Byway Description valuable qualities. Promoting tourism can Tse’nikani Scenic Byway, U.S. Highway be one target, but so are issues of safety or (US) 191 is located in northeast Arizona preserving historic or cultural structures. in Apache County and entirely within the 160 The Corridor Management Plan can: Navajo Nation. The portion of US 191 that 1 160 Tse’nikani is a designated Arizona Scenic Byway is Scenic Road ◊ document community interest from Milepost (MP) 467.0, south of Many ◊ document existing conditions and Farms, to MP 510.4, at the junction with history US 160, near Mexican Water. The highway ◊ guide enhancement and safety is the primary route to access Canyon de improvement projects ARIZONA Chelly National Monument, about 13 miles mexico new south of the south end of the byway. ◊ promote partnerships for conservation Chinle and enhancement activities US 191 is a two-lane asphalt paved road for ◊ suggest resources for project development almost its entire length with no median and programs and few left-turn lanes. The roadway is ◊ promote coordination between residents, managed by the Arizona Department communities, and agencies of Transportation (ADOT) through the 264 Ganado ◊ support application for National Scenic Navajo Nation. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Permian Stratigraphy of the Defiance Plateau, Arizona H

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/18 Permian stratigraphy of the Defiance Plateau, Arizona H. Wesley Peirce, 1967, pp. 57-62 in: Defiance, Zuni, Mt. Taylor Region (Arizona and New Mexico), Trauger, F. D.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 18th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 228 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1967 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation Item Type text; Proceedings Authors Tecle, Aregai; Heinrich, Paul; Leeper, John; Tallsalt-Robertson, Jolene Publisher Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Journal Hydrology and Water Resources in Arizona and the Southwest Rights Copyright ©, where appropriate, is held by the author. Download date 25/09/2021 20:12:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/301297 37 RAINFALL-RUNOFF MODEL FOR BLACK CREEK WATERSHED, NAVAJO NATION Aregai Tecle1, Paul Heinrich1, John Leeper2, and Jolene Tallsalt-Robertson2 ABSTRACT This paper develops a rainfall-runoff model for estimating surface and peak flow rates from precipitation storm events on the Black Creek watershed in the Navajo Nation. The Black Creek watershed lies in the southern part of the Navajo Nation between the Defiance Plateau on the west and the Chuska Mountains on the east. The area is in the semiarid part of the Colorado Plateau on which there is about 10 inches of precipitation a year. We have two main purposes for embarking on the study. One is to determine the amount of runoff and peak flow rate generated from rainfall storm events falling on the 655 square mile watershed and the second is to provide the Navajo Nation with a method for estimating water yield and peak flow in the absence of adequate data. Two models, Watershed Modeling System (WMS) and the Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC) Hydrological Modeling System (HMS) that have Geographic Information System (GIS) capabilities are used to generate stream hydrographs. Figure 1. Physiographic map of the Navajo Nation with the Chuska The latter show peak flow rates and total amounts of Mountain and Deance Plateau and Stream Gaging Stations. -

Grand Circle

Salt Lake City Green River - Moab Salt Lake City - Green River 60min (56mile) Grand Junction 180min (183mile) Colorado Crescent Jct. NM Great Basin Green River NP Arches NP Moab - Arches Goblin Valley 10min (5mile) SP Corona Arch Moab Grand Circle Map Capitol Reef - Green River Dead Horse Point 100min (90mile) SP Moab - Grand View Point NP: National Park 80min (45mile) NM: National Monument NHP: National Histrocal Park Bryce Canyon - Capitol Reef Canyonlands SP: State Park Capitol Reef COLORADO 170min (123mile) NP NP Moab - Mesa Verde Monticello Moab - Monument Valley 170min (140mile) NEVADA UTAH 170min (149mile) Bryce Cedar City Canyon NP Natural Bridges Canyon of the Cedar Breaks NM Blanding Ancients NM Mesa Verde - Monument Valley NM Kodacrome Basin SP 200min (150mile) Valley of Hovenweep 40min 70min NM Cortez (24mile) (60mile) Grand Staircase- the Gods 100min Escalante NM Durango Mt. Carmel (92mile) Muley Point Snow Canyon Jct. SP Goosenecks SP Zion NP Kanab Lake Powell Mexican Hat Mesa Verde Rainbow Monument Valley NP Coral Pink Sand Vermillion Page Bridge NM Four Corners Las Vegas - Zion Dunes SP Cliffs NM Navajo Tribal Park Aztec Ruins NM 170min (167mile) Antelope Pipe Spring NM Horseshoe Shiprock Aztec Bend Canyon Mesa Verde - Chinle 200min (166mile) Mt.Carmel Jct. - North Rim Navajo NM 140min (98mile) Kayenta Farmington Monument Valley - Chinle Mesa Verde - Chaco Culture Valley of Fire Page - North Rim Page - Cameron Page - Monument Valley 140min (134mile) 230min (160mile) SP 170min (124mile) 90min (83mile) Grand Canyon- 130min -

Oil and Gas Plays Ute Moutnain Ute Reservation, Colorado and New Mexico

Ute Mountain Ute Indian Reservation Cortez R18W Karle Key Xu R17W T General Setting Mine Xu Xcu 36 Can y on N Xcu McElmo WIND RIVER 32 INDIAN MABEL The Ute Mountain Ute Reservation is located in the northwest RESERVATION MOUNTAIN FT HALL IND RES Little Moude Mine Xcu T N ern portion of New Mexico and the southwestern corner of Colorado UTE PEAK 35 N R16W (Fig. UM-1). The reservation consists of 553,008 acres in Montezu BLACK 666 T W Y O M I N G MOUNTAIN 35 R20W SLEEPING UTE MOUNTAIN N ma and La Plata Counties, Colorado, and San Juan County, New R19W Coche T Mexico. All of these lands belong to the tribe but are held in trust by NORTHWESTERN 34 SHOSHONI HERMANO the U.S. Government. Individually owned lands, or allotments, are IND RES Desert Canyon PEAK N MESA VERDE R14W NATIONAL GREAT SALT LAKE W Marble SENTINEL located at Allen Canyon and White Mesa, San Juan County, Utah, Wash Towaoc PARK PEAK T and cover 8,499 acres. Tribal lands held in trust within this area cov Towaoc River M E S A 33 1/2 N er 3,597 acres. An additional forty acres are defined as U.S. Govern THE MOUND R15W SKULL VALLEY ment lands in San Juan County, Utah, and are utilized for school pur TEXAS PACIFIC 6-INCH OIL PIPELINE IND RES UNITAH AND OURAY INDIAN RESERVATION Navajo poses. W Ramona GOSHUTE 789 The Allen Canyon allotments are located twelve miles west of IND RES T UTAH 33 Blanding, Utah, and adjacent to the Manti-La Sal National Forest.