“Modern Nature”: Derek Jarman's Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

"THE POSSIBLES WE DARE": ART AND IDENTITY IN THE POETRY OF THEODORE ROETHKE Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Maselli, Sharon Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 14:20:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290470 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

The Fumarolic CO Output from Pico Do Fogo Volcano

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 139, No. 3 (2020), pp. 325-340, 9 figs., 3 tabs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.03) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2020 The fumarolic CO2 output from Pico do Fogo Volcano (Cape Verde) ALESSANDRO AIUPPA (1), MARCELLO BITETTO (1), ANDREA L. RIZZO (2), FATIMA VIVEIROS (3), PATRICK ALLARD (4), MARIA LUCE FREZZOTTI (5), VIRGINIA VALENTI (5) & VITTORIO ZANON (3, 4) ABSTRACT output started early back in the 1990s (e.g., GERLACH, 1991), The Pico do Fogo volcano, in the Cape Verde Archipelago off substantial budget refinements have only recently arisen the western coasts of Africa, has been the most active volcano in the from the 8-years (2011-2019) DECADE (Deep Earth Carbon Macaronesia region in the Central Atlantic, with at least 27 eruptions Degassing; https://deepcarboncycle.org/about-decade) during the last 500 years. Between eruptions fumarolic activity has research program of the Deep Carbon Observatory (https:// been persisting in its summit crater, but limited information exists for the chemistry and output of these gas emissions. Here, we use the deepcarbon.net/project/decade#Overview) (FISCHER, 2013; results acquired during a field survey in February 2019 to quantify FISCHER et alii, 2019). the quiescent summit fumaroles’ volatile output for the first time. By One key result of DECADE-funded research has been combining measurements of the fumarole compositions (using both a the recognition that the global CO2 output from subaerial portable Multi-GAS and direct sampling of the hottest fumarole) and volcanism is predominantly sourced from a relatively of the SO2 flux (using near-vent UV Camera recording), we quantify small number of strongly degassing volcanoes. -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

Craters of the Pluto-Charon System

Icarus 287 (2017) 187–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Craters of the Pluto-Charon system ∗ Stuart J. Robbins a, , Kelsi N. Singer a, Veronica J. Bray b, Paul Schenk c, Tod R. Lauer d, Harold A. Weaver e, Kirby Runyon e, William B. McKinnon f, Ross A. Beyer g,h, Simon Porter a, Oliver L. White h, Jason D. Hofgartner i, Amanda M. Zangari a, Jeffrey M. Moore h, Leslie A. Young a, John R. Spencer a, Richard P. Binzel j, Marc W. Buie a, Bonnie J. Buratti i, Andrew F. Cheng e, William M. Grundy k, Ivan R. Linscott l, Harold J. Reitsema m, Dennis C. Reuter n, Mark R. Showalter g,h, G. Len Tyler l, Catherine B. Olkin a, Kimberly S. Ennico h, S. Alan Stern a, the New Horizons LORRI, MVIC Instrument Teams a Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, United States b Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States c Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, United States d National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, AZ 85726, United States e The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States f Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States g SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Avenue, Suite 100, Mountain View CA 94043, United States h NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 84043, United States i NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, United States j Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States k Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ, United States l Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States m Ball Aerospace, Boulder, CO, United States n NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: NASA’s New Horizons flyby mission of the Pluto-Charon binary system and its four moons provided hu- Received 3 March 2016 manity with its first spacecraft-based look at a large Kuiper Belt Object beyond Triton. -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

GREAT Day 2007 Program

Welcome to SUNY Geneseo’s First Annual G.R.E.A.T. Day! Geneseo Recognizing Excellence, Achievement & Talent Day is a college-wide symposium celebrating the creative and scholarly endeavors of our students. In addition to recognizing the achievements of our students, the purpose of G.R.E.A.T. Day is to help foster academic excellence, encourage professional development, and build connections within the community. The G.R.E.A.T. Day Planning Committee: Doug Anderson, School of the Arts Anne Baldwin, Sponsored Research Joan Ballard, Department of Psychology Anne Eisenberg, Department of Sociology Charlie Freeman, Department of Physics & Astronomy Tom Greenfield, Department of English Anthony Gu, School of Business Koomi Kim, School of Education Andrea Klein, Scheduling and Special Events The Planning Committee would like to thank: Stacie Anekstein, Ed Antkoviak, Brian Bennett, Cassie Brown, Michael Caputo, Sue Chichester, Betsy Colon, Laura Cook, Ann Crandall, Joe Dolce, Tammy Farrell, Carlo Filice, Richard Finkelstein, Karie Frisiras, Ginny Geer-Mentry, Becky Glass, Dave Gordon, Corey Ha, John Haley, Doug Harke, Gregg Hartvigsen, Tony Hoppa, Paul Jackson, Ellen Kintz, Nancy Johncox, Enrico Johnson, Ken Kallio, Jo Kirk, Sue Mallaber, Mary McCrank, Nancy Newcomb, Elizabeth Otero, Tracy Paradis, Jennifer Perry, Jewel Reardon, Ed Rivenburgh, Linda Shepard, Bonnie Swoger, Helen Thomas, Pam Thomas, and Taryn Thompson. Thank you to President Christopher Dahl and Provost Katherine Conway-Turner for their support of G.R.E.A.T. Day. Thank you to Lynn Weber for delivering our inaugural keynote address. The G.R.E.A.T. Day name was suggested by Elizabeth Otero, a senior Philosophy major. -

WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor

“Weather-Proofing” Shenandoah. Fall, 1974: 18-19. WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor Acknowledgments Some of the poems in this manuscript have previously appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Centennial Review, Colorado Quarterly, Confrontation, Florida Quarterly, The Journal of Popular Film, The Little Magazine, Montana Gothic, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, Southern Poetry Review. Table of Contents I Weather-Proofing A Priest’s Mind . 1 Weather-Proofing . 2 Riding the Earth . 3 Small Consolation . 4 To the Poet as a Young Traveler . 6 The Fact of the Darkness . 7 Outside, Where Films End . 9 On Revisiting Tintern Abbey . 10 The Coming of the Ice: A Sestina . 11 House at the Beach . 13 Postcard from a Daughter in Crete . 15 Spinoza and Dostoevsky Tell Me About My Cousins . 16 Looking for Monday . 17 On the Absence of Moths Underseas . 18 II The Practical Life The Practical Life . 19 Taking the News . 21 In the Best of Health . 22 In the Center of the Soup . 23 Masks . 24 They Who Never Tire . 25 Decorum . 26 After Babi Yar . 27 Death of the Short-Term Memory . 29 Open-Ended . 30 Joys and Desires . 31 Snow on the Louvre . 32 Night Ferry to Helsinki . 33 The Unicorn and the Sea . 35 III Hovering Hovering . 36 Gestorben in Zurich . 37 In the Church of the Frari . 39 Death of an Audio Engineer . 40 For Georgio Morandi . 42 Piano Recital from Second Row Center . 43 In the Shade of Asclepius . 44 The Accident of Recovery . 45 On a Dish from the Ch’ing Dynasty . 46 Swallows on the Moon . -

The Tennessee Meteorite Impact Sites and Changing Perspectives on Impact Cratering

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND THE TENNESSEE METEORITE IMPACT SITES AND CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON IMPACT CRATERING A dissertation submitted by Janaruth Harling Ford B.A. Cum Laude (Vanderbilt University), M. Astron. (University of Western Sydney) For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT Terrestrial impact structures offer astronomers and geologists opportunities to study the impact cratering process. Tennessee has four structures of interest. Information gained over the last century and a half concerning these sites is scattered throughout astronomical, geological and other specialized scientific journals, books, and literature, some of which are elusive. Gathering and compiling this widely- spread information into one historical document benefits the scientific community in general. The Wells Creek Structure is a proven impact site, and has been referred to as the ‘syntype’ cryptoexplosion structure for the United State. It was the first impact structure in the United States in which shatter cones were identified and was probably the subject of the first detailed geological report on a cryptoexplosive structure in the United States. The Wells Creek Structure displays bilateral symmetry, and three smaller ‘craters’ lie to the north of the main Wells Creek structure along its axis of symmetry. The question remains as to whether or not these structures have a common origin with the Wells Creek structure. The Flynn Creek Structure, another proven impact site, was first mentioned as a site of disturbance in Safford’s 1869 report on the geology of Tennessee. It has been noted as the terrestrial feature that bears the closest resemblance to a typical lunar crater, even though it is the probable result of a shallow marine impact. -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

First Results of the Piton De La Fournaise STRAP 2015 Experiment: Multidisciplinary Tracking of a Volcanic Gas and Aerosol Plume

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 5355–5378, 2017 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/17/5355/2017/ doi:10.5194/acp-17-5355-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. First results of the Piton de la Fournaise STRAP 2015 experiment: multidisciplinary tracking of a volcanic gas and aerosol plume Pierre Tulet1, Andréa Di Muro2, Aurélie Colomb3, Cyrielle Denjean4, Valentin Duflot1, Santiago Arellano5, Brice Foucart1,3, Jérome Brioude1, Karine Sellegri3, Aline Peltier2, Alessandro Aiuppa6,7, Christelle Barthe1, Chatrapatty Bhugwant8, Soline Bielli1, Patrice Boissier2, Guillaume Boudoire2, Thierry Bourrianne4, Christophe Brunet2, Fréderic Burnet4, Jean-Pierre Cammas1,9, Franck Gabarrot9, Bo Galle5, Gaetano Giudice7, Christian Guadagno8, Fréderic Jeamblu1, Philippe Kowalski2, Jimmy Leclair de Bellevue1, Nicolas Marquestaut9, Dominique Mékies1, Jean-Marc Metzger9, Joris Pianezze1, Thierry Portafaix1, Jean Sciare10, Arnaud Tournigand8, and Nicolas Villeneuve2 1LACy, Laboratoire de l’Atmosphère et des Cyclones, UMR8105 CNRS, Université de La Réunion, Météo-France, Saint-Denis de La Réunion, France 2OVPF, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, UMR7154, CNRS, Université Sorbonne Paris-Cité, Université Paris Diderot, Bourg-Murat, La Réunion, France 3LaMP, Laboratoire de Météorologie Physique, UMR6016, CNRS, Université Blaise Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand, France 4CNRM, Centre National de la Recherche Météorologique, UMR3589, CNRS, Météo-France, Toulouse, France 5DESS, Department of Earth and Space Sciences, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden 6Dipartimento -

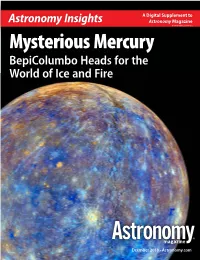

Mysterious Mercury Bepicolumbo Heads for the World of Ice and Fire

A Digital Supplement to Astronomy Insights Astronomy Magazine © 2018 Kalmbach Media Mysterious Mercury BepiColumbo Heads for the World of Ice and Fire Dcember 2018 • Astronomy.com Voyage to a world Color explodes from Mercury’s surface in this enhanced-color mosaic taken through several filters. The yellow and orange hues signify relatively young plains likely formed when fluid lavas erupted from volcanoes. Medium- and dark-blue regions are older terrain, while the light-blue and white streaks represent fresh material excavated from relatively recent impacts. ALL IMAGES, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED: NASA/JHUAPL/CIW 2 ASTRONOMY INSIGHTS • DECEMBER 2018 A world of both fire and ice, Mercury excites and confounds scientists. The BepiColombo probe aims to make sense of this mysterious world. by Ben Evans of extremesWWW.ASTRONOMY.COM 3 Mercury is a land of contrasts. The solar system’s smallest planet boasts the largest core relative to its size. Temperatures at noon can soar as high as 800 degrees Fahrenheit (425 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt lead — but dip as low as –290 F (–180 C) before dawn. Mercury resides nearest the Sun, and it has the most eccentric orbit. At its closest, the planet lies only 29 mil- lion miles (46 million kilometers) from the Sun — less than one-third Earth’s distance — but swings out as far as 43 million miles (70 million km). Its rapid movement across our sky earned it a reputation among ancient skywatchers as the fleet-footed messenger of the gods: Italian scientist Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo helped develop a technique for sending a space Hermes to the Greeks and Mercury to the Romans.