THE WILSON QUARTERLY Y:::-- ..

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

"THE POSSIBLES WE DARE": ART AND IDENTITY IN THE POETRY OF THEODORE ROETHKE Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Maselli, Sharon Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 14:20:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290470 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

L Rathnam Dissertation

The Politics of Skepticism: Montaigne and Zhuangzi on Freedom, Toleration, and the Limits of Government by Lincoln Edward Ford Rathnam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Lincoln Edward Ford Rathnam 2018 ii The Politics of Skepticism: Montaigne and Zhuangzi on Freedom, Toleration, and the Limits of Government Lincoln Rathnam Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science 2018 Abstract: Contemporary political discourse often centers on a shared set of normative commitments: freedom, toleration, and limited government. This dissertation examines the theoretical basis for these commitments, through a comparative study of two eminent skeptics: Michel de Montaigne and Zhuangzi. Both develop forms of skepticism that are rooted in analyses of the phenomena of diversity and disagreement. They contend that our inability to reach convergence on central philosophical questions demonstrates the fundamental limitations of human knowledge. I argue that both offer novel and powerful arguments connecting these skeptical epistemological theses with the relevant normative commitments. In particular, both take skepticism to advance human freedom, by clearing away obstacles to effective action. As beings who are raised within a particular community, we inevitably acquire certain habits that constrain the forms of thought and action open to us. Skepticism helps us to recognize the contingency of those forms. In the interpersonal realm, both writers contend that skepticism generates an attitude of toleration towards others who live differently. This is because it undermines the theoretical claims upon which most forms of intolerance are constructed. I defend this claim with reference to the various forms of intolerance that existed in each writer’s context, Warring States era China and France during the Wars of Religion. -

History and Drafting of Hose By: Adelheid Holtzhauer

History and Drafting of Hose By: Adelheid Holtzhauer Introduction Leg coverings of some sort have been worn throughout history by both men and women. For the purposes of this class, the hose we will be looking at are fitted, closed footed and made of woven fabric. There are many garments called Hose and Hosen worn throughout history. Extant examples have been found dating back to the 2nd century such as the footed hose found a Martres-de- Veyre. Image 1: Womens woollen twill hose excavated at Martres-de-Veyre Although there are many different garments that could be referred to as hose, in this class we will be focusing on "Single Hose" and "Attached Hose". Single hose cover one leg and can vary in length/height. Attached hose are essentially tight fitted trews. Over the course of time, single hose went from knee length and gartered with trim, to full fitted "pants" to thigh high and attached with to a belt at the waist, to detached and gartered under the knee to the full legging style common in the late 161h century. Image 2 shows a pair of attached hose which are carbon dated to 1355 AD and were found in the Damendorf Bog. Image 2: Susan Moller- Image 4: After a photo in Wlering: War and worship, p Nockert: 114 Bockstenmannen och Image 3: Margareta hans drakt Nockert: Bockstenmannen och hans drakt. pg 61 The knee high hose in image 3 were found on the Bocksten Bog Man generally dated to the th 14 century but were carbon dated between 1290 and 1430. -

Marc D. Guerra, Ph.D

Marc D. Guerra, Ph.D. Theology Department, Assumption College, 500 Salisbury Street, Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 Office (508) 767-7575; Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph. D. Ave Maria University (Theology) Naples, Florida (May 2007) M.A. Assumption College (Theology) Worcester, Massachusetts (May 1994) B.A. Assumption College (Psychology) Worcester, Massachusetts (May 1990) ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Assumption College (Worcester, Massachusetts) Professor (2016-) Director of Core Texts and Enduring Questions Program (2016-) Associate Professor (2012-2016) Theology Department Chair (2012-) Ave Maria University (Naples, Florida) Associate Professor (2010-2012) Director of Graduate Programs in Theology (2007-2012) Assistant Professor of Theology (2004-2009) Assumption College (Worcester, Massachusetts) Instructor of Theology (1999-2004) SCHOLARLY CONCENTRATION Relationship between Faith and Reason Catholicism and the Political Order Pope Benedict XVI PUBLICATIONS AUTHORED BOOKS Christians as Political Animals: Taking the Measure of Modernity and Modern Democracy (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2010). EDITED BOOKS Liberating Logos: Pope Benedict XVI’s September Speeches (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2014) Pope Benedict XVI and the Politics of Modernity (London: Routledge Publications, 2014). Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome: Essays in Honor of James V. Schall, S.J. (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2013). 1 The Science of Modern Virtue: On Descartes, Darwin, and Locke, coedited with Peter Augustine Lawler (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2013). Reason, Revelation, and Human Affairs: Selected Writings of James V. Schall (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2001). ARTICLES AND ESSAYS “Scientist, Scholar, Soul” in The New Atlantis, (48) Spring/Summer 2016. 110-120. “Moderating the Magnanimous Man: Aquinas on Greatness of Soul” in Theology Needs Philosophy: Essays in Honor of Ralph McInerny, edited by Matthew L. -

2017 Fall Event Brochure

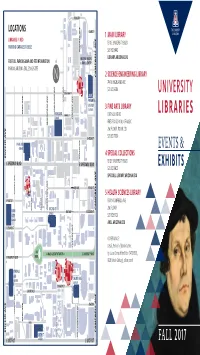

RING RD LOCATIONS ELM ST 1 MAIN LIBRARY LIBRARIES IN RED 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD PARKING GARAGES IN BLUE WARREN AVE WARREN 520.621.6442 ARIZONA HEALTH LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU FOR FULL PARKING MAP AND FEE INFORMATION SCIENCES CENTER PARKING.ARIZONA.EDU, 520.626.7275 CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL 2 SCIENCE-ENGINEERING LIBRARY 744 N HIGHLAND AVE 520.621.6384 E DRACHMAN ST UAMC VINE AVE PATIENT & VISITOR GARAGE 3 FINE ARTS LIBRARY HIGHLAND AVE PARK AVE PARK HIGHLAND E MABEL ST 1017 N OLIVE RD GARAGE AVE CHERRY FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN 2nd FLOOR, ROOM 233 E HELEN ST 520.621.7009 PARK AVE GARAGE 4 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS EUCLID AVE WARREN AVE WARREN 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD 520.621.6423 SPECCOLL.LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU ONE WAY E FIRST ST MUSIC TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL BLDG 5 HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY E FIRST ST 1501 N CAMPBELL AVE MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL PALM DR PALM OLIVE RD SECOND ST 2nd FLOOR MAIN ONE WAY E SECOND ST GATE GARAGE 520.626.6125 GARAGE AHSL.ARIZONA.EDU E SECOND ST COVER IMAGE: CHERRY AVE CHERRY Detail, Portrait of Martin Luther, OLD MALL CLOSED TO TRAFFIC E UNIVERSITY BLVD by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), MAIN E UNIVERSITY BLVD 1528 (Veste Coburg), oil on panel TYNDALL AVE GARAGE CHERRY AVE GARAGE E FOURTH ST E FOURTH ST CHERRY AVE CHERRY ENKE DR TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL PARK AVE PARK LOWELL CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL EUCLID AVE NAT’L CHAMPIONS DR CHAMPIONS NAT’L SIXTH ST HIGHLAND AVE E SIXTH ST GARAGE E SIXTH ST FALL 2017 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SPECIAL EVENTS speccoll.library.arizona.edu Library Cats Tech Breakfast Contact: Kathy McCarthy | 520.626.8332 Saturday, October 28, 9–11 a.m., Science-Engineering Library [email protected] All alumni and friends are welcome at our Homecoming EXHIBIT | Opens August 7 celebration. -

The Fumarolic CO Output from Pico Do Fogo Volcano

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 139, No. 3 (2020), pp. 325-340, 9 figs., 3 tabs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2020.03) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2020 The fumarolic CO2 output from Pico do Fogo Volcano (Cape Verde) ALESSANDRO AIUPPA (1), MARCELLO BITETTO (1), ANDREA L. RIZZO (2), FATIMA VIVEIROS (3), PATRICK ALLARD (4), MARIA LUCE FREZZOTTI (5), VIRGINIA VALENTI (5) & VITTORIO ZANON (3, 4) ABSTRACT output started early back in the 1990s (e.g., GERLACH, 1991), The Pico do Fogo volcano, in the Cape Verde Archipelago off substantial budget refinements have only recently arisen the western coasts of Africa, has been the most active volcano in the from the 8-years (2011-2019) DECADE (Deep Earth Carbon Macaronesia region in the Central Atlantic, with at least 27 eruptions Degassing; https://deepcarboncycle.org/about-decade) during the last 500 years. Between eruptions fumarolic activity has research program of the Deep Carbon Observatory (https:// been persisting in its summit crater, but limited information exists for the chemistry and output of these gas emissions. Here, we use the deepcarbon.net/project/decade#Overview) (FISCHER, 2013; results acquired during a field survey in February 2019 to quantify FISCHER et alii, 2019). the quiescent summit fumaroles’ volatile output for the first time. By One key result of DECADE-funded research has been combining measurements of the fumarole compositions (using both a the recognition that the global CO2 output from subaerial portable Multi-GAS and direct sampling of the hottest fumarole) and volcanism is predominantly sourced from a relatively of the SO2 flux (using near-vent UV Camera recording), we quantify small number of strongly degassing volcanoes. -

Wall Free Climb in the World by Tommy Caldwell

FREE PASSAGE Finding the path of least resistance means climbing the hardest big- wall free climb in the world By Tommy Caldwell Obsession is like an illness. At first you don't realize anything is happening. But then the pain grows in your gut, like something is shredding your insides. Suddenly, the only thing that matters is beating it. You’ll do whatever it takes; spend all of your time, money and energy trying to overcome. Over months, even years, the obsession eats away at you. Then one day you look in the mirror, see the sunken cheeks and protruding ribs, and realize the toll taken. My obsession is a 3,000-foot chunk of granite, El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. As a teenager, I was first lured to El Cap because I could drive my van right up to the base of North America’s grandest wall and start climbing. I grew up a clumsy kid with bad hand-eye coordination, yet here on El Cap I felt as though I had stumbled into a world where I thrived. Being up on those steep walls demanded the right amount of climbing skill, pain tolerance and sheer bull-headedness that came naturally to me. For the last decade El Cap has beaten the crap out of me, yet I return to scour its monstrous walls to find the tiniest holds that will just barely go free. So far I have dedicated a third of my life to free climbing these soaring cracks and razor-sharp crimpers. Getting to the top is no longer important. -

El Capitan, the Direct Line California, Yosemite National Park the Direct Line (39 Pitches, 5.13+), A.K.A

AAC Publications El Capitan, The Direct Line California, Yosemite National Park The Direct Line (39 pitches, 5.13+), a.k.a. the Platinum Wall, is a brand-new, mostly independent free line on El Capitan. It begins just left of the Nose and continues up the steepening blankness, following a circuitous path of 22 technical slab pitches before accessing the upper half of the Muir, either by the PreMuir (recommended) or the Shaft. From where these two routes meet, it continues up the aesthetic upper Muir corner system to access wild and overhanging terrain on the right wall. Bolted pitches take you to the prow between the Muir and Nose, and the route finishes close to the original Muir. In 2006, envisioning a possible variation to the Nose, Justen Sjong and I had explored multiple possibilities for exiting the Half Dollar on the Salathé Wall route and finding some way to access Triple Direct Ledge, 80’ below Camp IV on the Nose. Beginning in 2010, I picked up where we left off and began searching for the definitive free climbing path. During that hot and dry summer in 2010, it becameclear there was a much more direct and independent way to climb the slabs to Triple Direct Ledge than using the Freeblast start to the Salathé. With that exciting realization, I just couldn’t see finishing on the Nose, but instead envisioned a nearly independent route all the way up the wall. I took it on faith that there had to be a way to exit the Muir corner. Each tantalizing prospect on the upper wall would either yield a new approach or would clarify a dead end (which is also helpful). -

Galen Clark's Library

YOSEMITE VOLUME XXXVIII - NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1959 IN COOPERATION •ITH THE NATIONAL PARR . SERVICE. In 1857, when 43 years of age, Galen Clark (left) was told that he had not long to live and should move from Mariposa to a more favorable climate of a higher elevation . This led t, his settling on the South Fork of the Merced River, at present day Wawona, and establishino a hotel to accommodate early-day visitors to Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove . Clar4 died in 1910 at the ripe old age of 96. COVER — Galen Clark, Yosemite ' s first Guardian, at the base of the Grizzly Giant. —Photo by Watktus, 181t~ yosemite Since 1922, the monthly publication of the National Park Service and the Yosemite Natural NAILER! NOTE S History Association in Yosemite National Park. John C . Preston, Park Superintendent Douglass H . Hubbard, Park Naturalist Robert F. Upton, Associate Park Naturalist D^'tl F . McCrary, Assistant Park Naturalist Herbert D . Cornell, Junior Park Naturalist Keith A . Trexler, Park Naturalist Trainee 1 WOK., XXXVHI DEC'EAIBLR 1959 NO . 12 GALEN CLARK'S LIBRARY by Jim Fox, Ranger-Naturalist Probably the most revered pioneer Lodge of the Sierra Club, to which hi Yosemite history was Galen Clark . he was a charter member . They are In 1855 he first saw the Valley, and there now, kept in Yosemite Valley lit 1857 he established the first hostel available to the public. at what is now Wawona. It was at A survey of the books in the Galen that time the halfway point on the Clark Collection is of interest to the trail from Mariposa to Yosemite Val- historian as it may shed some light lay and was known as Clark 's on the interests of Clark. -

Chapter 12 the Moon and Mercury: Comparing Airless Worlds The

11/4/2015 The Moon: The View from Earth From Earth, we always see the same side of the moon. Moon rotates around its axis in the same time that it takes to orbit Chapter 12 around Earth: The Moon and Mercury: Tidal coupling: Earth’s gravitation has Comparing Airless Worlds produced tidal bulges on the moon; Tidal forces have slowed rotation down to same period as orbital period Lunar Surface Features Highlands and Lowlands Two dramatically Sinuous rilles = different kinds of terrain: remains of ancient • Highlands: lava flows Mountainous terrain, scarred by craters May have been lava • Lowlands: ~ 3 km lower than highlands; smooth tubes which later surfaces: collapsed due to Maria (pl. of mare): meteorite bombardment. Basins flooded by Apollo 15 lava flows landing site The Highlands Impact Cratering Saturated with craters Impact craters on the moon can be seen easily even with small telescopes. Older craters partially … or flooded by Ejecta from the impact can be seen as obliterated by more lava flows bright rays originating from young recent impacts craters 1 11/4/2015 History of Impact Cratering Missions to the Moon Rate of impacts due to Major challenges: interplanetary Need to carry enough fuel for: bombardment decreased • in-flight corrections, rapidly after the formation of the solar system. • descent to surface, • re-launch from the surface, • return trip to Earth; Most craters seen on the need to carry enough food and other moon’s (and Mercury’s) life support for ~ 1 week for all surface were formed astronauts on board. Lunar module (LM) of within the first ~ ½ billion Solution: Apollo 12 on descent to the years.