Violent Imaginaries and the Maintenance of a War Mood in Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esi Document Id 128.Pdf

Generation Facebook in Baku Adnan, Emin and the Future of Dissent in Azerbaijan Berlin – Istanbul 15 March 2011 “... they know from their own experience in 1968, and from the Polish experience in 1980-1981, how suddenly a society that seems atomized, apathetic and broken can be transformed into an articulate, united civil society. How private opinion can become public opinion. How a nation can stand on its feet again. And for this they are working and waiting, under the ice.” Timothy Garton Ash about Charter 77 in communist Czechoslovakia, February 1984 “How come our nation has been able to transcend the dilemma so typical of defeated societies, the hopeless choice between servility and despair?” Adam Michnik, Letter from the Gdansk Prison, July 1985 Table of contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... I Cast of Characters .......................................................................................................................... II 1. BIRTHDAY FLOWERS ........................................................................................................ 1 2. A NEW GENERATION ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Birth of a nation .............................................................................................................. 4 B. How (not) to make a revolution ..................................................................................... -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Painful Past, Fragile Future the Delicate Balance in the Western Balkans Jergović, Goldsworthy, Vučković, Reka, Sadiku Kolozova, Szczerek and Others

No 2(VII)/2013 Price 19 PLN (w tym 5% VAT) 10 EUR 12 USD 7 GBP ISSN: 2083-7372 quarterly April-June www.neweasterneurope.eu Painful Past, Fragile Future The delicate balance in the Western Balkans Jergović, Goldsworthy, Vučković, Reka, Sadiku Kolozova, Szczerek and others. Strange Bedfellows: A Question Ukraine’s oligarchs and the EU of Solidarity Paweï Kowal Zygmunt Bauman Books & Reviews: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Mykola Riabchuk, Robert D. Kaplan and Jan Švankmajer Seversk: A New Direction A Siberian for Transnistria? Oasis Kamil Caïus Marcin Kalita Piotr Oleksy Azerbaijan ISSN 2083-7372 A Cause to Live For www.neweasterneurope.eu / 13 2(VII) Emin Milli Arzu Geybullayeva Nominated for the 2012 European Press Prize Dear Reader, In 1995, upon the declaration of the Dayton Peace Accords, which put an end to one of the bloodiest conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, the Bosnian War, US President, Bill Clinton, announced that leaders of the region had chosen “to give their children and their grandchildren the chance to lead a normal life”. Today, after nearly 20 years, the wars are over, in most areas peace has set in, and stability has been achieved. And yet, in our interview with Blerim Reka, he echoes Clinton’s words saying: “It is the duty of our generation to tell our grandchildren the successful story of the Balkans, different from the bloody Balkans one which we were told about.” This and many more observations made by the authors of this issue of New Eastern Europe piece together a complex picture of a region marred by a painful past and facing a hopeful, yet fragile future. -

Combatting and Preventing Corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How Anti-Corruption Measures Can Promote Democracy and the Rule of Law

Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Silvia Stöber Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 4 Contents Contents 1. Instead of a preface: Why (read) this study? 9 2. Introduction 11 2.1 Methodology 11 2.2 Corruption 11 2.2.1 Consequences of corruption 12 2.2.2 Forms of corruption 13 2.3 Combatting corruption 13 2.4 References 14 3. Executive Summaries 15 3.1 Armenia – A promising change of power 15 3.2 Azerbaijan – Retaining power and preventing petty corruption 16 3.3 Georgia – An anti-corruption role model with dents 18 4. Armenia 22 4.1 Introduction to the current situation 22 4.2 Historical background 24 4.2.1 Consolidation of the oligarchic system 25 4.2.2 Lack of trust in the government 25 4.3 The Pashinyan government’s anti-corruption measures 27 4.3.1 Background conditions 27 4.3.2 Measures to combat grand corruption 28 4.3.3 Judiciary 30 4.3.4 Monopoly structures in the economy 31 4.4 Petty corruption 33 4.4.1 Higher education 33 4.4.2 Health-care sector 34 4.4.3 Law enforcement 35 4.5 International implications 36 4.5.1 Organized crime and money laundering 36 4.5.2 Migration and asylum 36 4.6 References 37 5 Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 5. -

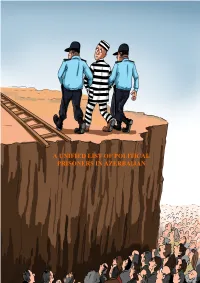

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

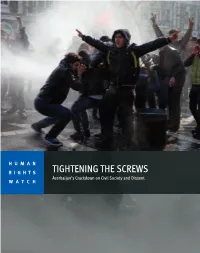

Azerbaijan0913 Forupload 1.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Report Following Her Visit to Azerbaijan from 8 to 12 July 2019

Strasbourg, 11 December 2019 CommDH(2019)27 English only COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE DUNJA MIJATOVIĆ REPORT FOLLOWING HER VISIT TO AZERBAIJAN FROM 8 TO 12 JULY 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 1 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION ...................................................................................................... 8 1.1 The arbitrary application of criminal legislation to restrict freedom of expression ................ 8 1.1.1 Arrests and detention ............................................................................................................ 8 1.1.2 Restrictions on the right to leave the country ..................................................................... 10 1.1.3 Conclusions and recommendations ..................................................................................... 11 1.2 Defamation........................................................................................................................12 1.2.1 Conclusions and recommendations ..................................................................................... 13 1.3 Internet restrictions ...........................................................................................................13 1.3.1 Conclusions and recommendations .................................................................................... -

Echo of Khojaly Tragedy

CHAPTER 3 ECHO OF KHOJALY Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── CONTENTS Kommersant (Moscow) (February 27, 2002) ..................................................................................... 15 15 th year of Khojaly genocide commemorated (February 26, 2007) ................................................ 16 Azerbaijani delegation to highlight Nagorno-Karabakh issue at OSCE PA winter session (February 3, 2008) ............................................................................................................................................... 17 On this night they had no right even to live (February 14, 2008) ...................................................... 18 The horror of the night. I witnessed the genocide (February 14-19, 2008) ....................................... 21 Turkey`s NGOs appeal to GNAT to recognize khojaly tragedy as genocide (February 13, 2008) ... 22 Azerbaijani ambassador meets chairman of Indonesian Parliament’s House of Representatives (February 15, 2008) ............................................................................................................................ 23 Anniversary of Khojaly genocide marked at Indonesian Institute of Sciences (February 18, 2008). 24 Round table on Khojaly genocide held in Knesset (February 20, 2008) ........................................... 25 Their only «fault» was being Azerbaijanis (February -

IS AZERBAIJAN BECOMING a HUB of RADICAL ISLAM? Arzu

IS AZERBAIJAN BECOMING A HUB OF RADICAL ISLAM? In this article, the author attempts to explain the leading factors behind grow- ing Islamic infl uence in Azerbaijan. She describes social, political and economic problems as main triggers of Islam gaining stronghold across the country. The author argues that as a result of continued problems such as corruption, poverty, and semi-authoritarian government combined with disillusionment with the West and support of various religious sects from countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, Ku- wait, the rise of fundamental Islam has been inevitable. Arzu Geybullayeva* * The author is Analyst of the European Stability Initiative (ESI) covering Azerbaijan. 109 n the outside, Azerbaijan, an ex-Soviet Republic appears to be a rather remarkable example of progressive and secular Islamic state. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the newly formed Azerbaijani government immediately proclaimed itself Oa secular nation. The main inspiration was the secular ideology adopted from Turkey as a result of accession to power of the Azerbaijani Popular Front led by Abulfaz Elchibey. It was during Elchibey’s short lived presidency between 1992 and 1993 in which he pursued a Turkey-leaning stance that the notion of secularism began to gain a stronghold. During this period Turkey moved swiftly to fi ll the religious and ideological vacuum left by Russia. Elchibey’s positive attitude towards Turkey not only strengthened economic and political ties with the country, but also played an important role in adopting the Turkish model of strong nationalism and secularism. Yet, over the last few years, Islamic ideology has become visibly pronounced in Azerbaijan. -

Is Azerbaijan Becoming a Hub of Radical Islam?

IS AZERBAIJAN BECOMING A HUB OF RADICAL ISLAM? In this article, the author attempts to explain the leading factors behind growing Islamic influence in Azerbaijan. She describes social, political and economic problems as main triggers of Islam gaining stronghold across the country. The author argues that as a result of continued problems such as corruption, poverty, and semi-authoritarian government combined with disillusionment with the West and support of various religious sects from countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the rise of fundamental Islam has been inevitable. Arzu Geybullayeva* * The author is Analyst of the European Stability Initiative (ESI) covering Azerbaijan. On the outside, Azerbaijan, an ex-Soviet Republic appears to be a rather remarkable example of progressive and secular Islamic state. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early ‘90s, the newly formed Azerbaijani government immediately proclaimed itself a secular nation. The main inspiration was the secular ideology adopted from Turkey as a result of accession to power of the Azerbaijani Popular Front led by Abulfaz Elchibey. It was during Elchibey’s short lived presidency between 1992 and 1993 in which he pursued a Turkey-leaning stance that the notion of secularism began to gain a stronghold. During this period Turkey moved swiftly to fill the religious and ideological vacuum left by Russia. Elchibey’s positive attitude towards Turkey not only strengthened economic and political ties with the country, but also played an important role in adopting the Turkish model of strong nationalism and secularism. Yet, over the last few years, Islamic ideology has become visibly pronounced in Azerbaijan. -

Crackdown on Civil Society in Azerbaijan

No. 70 26 February 2015 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh resourcesecurityinstitute.org www.laender-analysen.de www.css.ethz.ch/cad www.crrccenters.org CraCkdown on Civil SoCiety in azerbaijan ■■The Best Defense is a Good Offense: The Role of Social Media in the Current Crackdown in Azerbaijan 2 By Katy E. Pearce, University of Washington ■■No Holds Barred: Azerbaijan’s Unprecedented Crackdown on Human Rights 6 By Rebecca Vincent, London ■■Does Advocacy Matter in Dealing with Authoritarian Regimes? 9 By Arzu Geybullayeva, Prague ■■ChroniCle From 27 January to 23 February 2015 14 ■■ConferenCe / Call for PaPers 4th ASCN Annual Conference “Protest, Modernization, Democratization: Political and Social Dynamics in Post-Soviet Countries” 16 Institute for European, Russian, Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for and Eurasian Studies for East European Studies for Security Studies The George Washington Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University The Caucasus Analytical Digest is supported by: CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 70, 26 February 2015 2 The Best Defense is a Good offense: The role of social Media in the Current Crackdown in azerbaijan By Katy E. Pearce, University of Washington abstract While Azerbaijan has been on the path to full-fledged authoritarianism for quite some time, the increased repression of 2013 and 2014 is, to many Azerbaijan watchers, unprecedented. Other articles in this issue detail the legislative and practical actions taken by the regime over the past few years. This piece focuses on the role of social media with historical contextualization. introduction most importantly, the Internet can provide more news Many pundits give too much credit to the role of infor- and information alternatives to state-provided media. -

Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 03 September 2019 Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 THE DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS ...................................................................... 4 POLITICAL PRISONERS ................................................................................................................. 5 A. JOURNALISTS AND BLOGGERS ......................................................................................... 5 B. HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS ........................................................................................ 13 C. POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVISTS ............................................................................ 14 A case of financing of the opposition party ............................................................... 20 D. RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS ...................................................................................................... 25 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and people arrested in Nardaran Settlement .............................................................................................................................. 25 (2) Religious activists arrested in Masalli in 2012 ................................................. 51 (3) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested together with him .................................................................................................................................