HISTORY MATTERS an Undergraduate Journal of Historical Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2

sUMMER 2017 • Volume 26 • Number 2 Welcome Home “Son, we’re moving to Oregon.” Hearing these words as a high school freshman in sunny Southern California felt – to a sensitive teenager – like cruel and unusual punishment. Save for an 8-bit Oregon Trail video game that always ended with my player dying of dysentery, I knew nothing of this “Oregon.” As proponents extolled the virtues of Oregon’s picturesque Cascade Mountains, I couldn’t help but mourn the mountains I was leaving behind: Space, Big Thunder and the Matterhorn (to say nothing of Splash, which would open just months after our move). I was determined to be miserable. But soon, like a 1990s Tom Hanks character trying to avoid falling in love with Meg Ryan, I succumbed to the allure of the Pacific Northwest. I learned to ride a lawnmower (not without incident), adopted a pygmy goat and found myself enjoying things called “hikes” (like scenic drives without the car). I rafted white water, ate pink salmon and (at legal age) acquired a taste for lemon wedges in locally produced organic beer. I became an obnoxiously proud Oregonian. So it stands to reason that, as adulthood led me back to Disney by way of Central Florida, I had a special fondness for Disney’s Wilderness Lodge. Inspired by the real grandeur of the Northwest but polished in a way that’s unmistakably Disney, it’s a place that feels perhaps less like the Oregon I knew and more like the Oregon I prefer to remember (while also being much closer to Space Mountain). -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Image – Action – Space

Image – Action – Space IMAGE – ACTION – SPACE SITUATING THE SCREEN IN VISUAL PRACTICE Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner (Eds.) This publication was made possible by the Image Knowledge Gestaltung. An Interdisciplinary Laboratory Cluster of Excellence at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (EXC 1027/1) with financial support from the German Research Foundation as part of the Excellence Initiative. The editors like to thank Sarah Scheidmantel, Paul Schulmeister, Lisa Weber as well as Jacob Watson, Roisin Cronin and Stefan Ernsting (Translabor GbR) for their help in editing and proofreading the texts. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Copyrights for figures have been acknowledged according to best knowledge and ability. In case of legal claims please contact the editors. ISBN 978-3-11-046366-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046497-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046377-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956404 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche National bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org and https://www.oapen.org. Cover illustration: Malte Euler Typesetting and design: Andreas Eberlein, aromaBerlin Printing and binding: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhalt 7 Editorial 115 Nina Franz and Moritz Queisner Image – Action – Space. -

No. 40. the System of Lunar Craters, Quadrant Ii Alice P

NO. 40. THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT II by D. W. G. ARTHUR, ALICE P. AGNIERAY, RUTH A. HORVATH ,tl l C.A. WOOD AND C. R. CHAPMAN \_9 (_ /_) March 14, 1964 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central-peak information, and state of completeness arc listed for each discernible crater in the second lunar quadrant with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km. The catalog contains more than 2,000 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. his Communication is the second part of The However, since we also have suppressed many Greek System of Lunar Craters, which is a catalog in letters used by these authorities, there was need for four parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable some care in the incorporation of new letters to certainty on photographs and having diameters avoid confusion. Accordingly, the Greek letters greater than 3.5 kilometers. Thus it is a continua- added by us are always different from those that tion of Comm. LPL No. 30 of September 1963. The have been suppressed. Observers who wish may use format is the same except for some minor changes the omitted symbols of Blagg and Miiller without to improve clarity and legibility. The information in fear of ambiguity. the text of Comm. LPL No. 30 therefore applies to The photographic coverage of the second quad- this Communication also. rant is by no means uniform in quality, and certain Some of the minor changes mentioned above phases are not well represented. Thus for small cra- have been introduced because of the particular ters in certain longitudes there are no good determi- nature of the second lunar quadrant, most of which nations of the diameters, and our values are little is covered by the dark areas Mare Imbrium and better than rough estimates. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

The Channel Dash April 26

The Channel Dash April 26 On the night of February 11, 1942, two German battleships, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, along with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen left anchor at Brest, France. This was be the beginning of the “Channel Dash” (Operation Thunderbolt-Cerberus) of February The Prinz Eugen 11-13 in which these three ships, despite pursuit by the British Royal Navy and Air Force (RAF), returned intact to Germany via the English Channel. The Dash was ordered by German leader Adolf Hitler—against the advice of his admirals, who believed his plan meant certain destruction for these ships. Yet Hitler expressed the following opinion: “The ships must leave port in daytime as we are dependent on the element of surprise…I don’t think the British capable of making and carrying out lightning decisions.” This time, Hitler was correct. How did the German ships end up in Brest, France? And why was it necessary for them to even make a Channel dash? Germany and Great Britain had been at war since 1939. By the summer of 1940, the seemingly unstoppable Germans had overrun much of the western portion of continental Europe. This included part of France, allowing them use of the port of Brest on the lower end of the English Channel for their surface ships and submarines. The Royal Navy attempted to blockade the Atlantic coast ports, but its resources were stretched thin. The British had been watching German vessels at Brest carefully. In fact, these three ships had been undergoing repairs there for much of 1941. -

Information, Tickets & Tours

INFORMATION, TICKETS & TOURS Located inside the Elmore Marine Corps Exchange Hours of Operation Address: 1251 Yalu St. Norfolk, VA 23515 Mon-Fri: 1000 – 1800 Ph: 757-423-1187 ext. 206 Sat: 0900 – 1400 www.MCCSHamptonRoads.com Sun/Holidays: CLOSED www.facebook.com/MCXTicketOffice AMUSEMENT PARKS & ATTRACTIONS Updated 12/05/2019 MOVIE THEATERS The ADVENTURE PARK @Va Aquarium (3hr ticket) AMC Cinemas (Nationwide) $10.00 Gate Price varies Adult $41.75 Gate Price $56.00 Regal Cinemas (Unrestricted) $9.50 Gate Price varies Youth (7-11) $35.00 Gate Price $48.00 Cinema Café $6.00 Gate Price varies Child (5-6) $29.25 Gate Price $32.50 VIRGINIA LURAY CAVERNS Adult $24.00 Gate Price $30.00 AMERICAN ROVER Child (6-12) $11.50 Gate Price $15.00 Harbor Cruise Adult $22.00 Gate Price $25.00 Ticket includes Luray Caverns tour, the Car & Carriage Caravan, access to the Luray Valley Museum and free admission to Toy Town Junction. Child (4-12) $13.25 Gate Price $15.00 Luray Caverns is open every day of the year. Tours depart approximately Sunset Cruise Adult $27.50 Gate Price $30.00 every twenty minutes. Tours begin each day at 9 AM. Child (4-12) $17.75 Gate Price $20.00 Luray Valley Museum opens at 10 AM and close 1 and a half hours after the Ticket valid thru 01/27/2020. Reservations are required. last tour of the day enters the Caverns. Located 10 minutes from the central entrance to Skyline Drive and VICTORY ROVER CRUISE Shenandoah National Park. Children 5 years and under are free. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(S): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed Work(S): Source: American Art, Vol

Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream Author(s): Karal Ann Marling Reviewed work(s): Source: American Art, Vol. 5, No. 1/2 (Winter - Spring, 1991), pp. 168-207 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109036 . Accessed: 06/12/2011 16:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Art. http://www.jstor.org Disneyland,1955 Just Takethe SantaAna Freewayto theAmerican Dream KaralAnn Marling The opening-or openings-of the new of the outsideworld. Some of the extra amusementpark in SouthernCalifornia "invitees"flashed counterfeit passes. did not go well. On 13 July, a Wednes- Othershad simplyclimbed the fence, day, the day of a privatethirtieth anniver- slippinginto the parkin behind-the-scene saryparty for Walt and Lil, Mrs. Disney spotswhere dense vegetation formed the herselfwas discoveredsweeping the deck backgroundfor a boat ride througha of the steamboatMark Twainas the first make-believeAmazon jungle. guestsarrived for a twilightshakedown Afterwards,they calledit "Black cruise.On Thursdayand Friday,during Sunday."Anything that could go wrong galapreopening tributes to Disney film did. -

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

San Diego Zoo / Safari Park

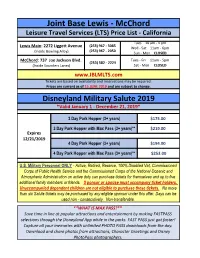

Joint Base Lewis - McChord Leisure Travel Services (LTS) Price List - California Tues 10 am - 4 pm (253) 967 - 3085 Lewis Main: 2272 Liggett Avenue Wed - Sat 11am - 6pm (253) 967 - 2050 (Inside Bowling Alley) Sun - Mon CLOSED McChord: 737 Joe Jackson Blvd. Tues - Fri 11am - 5pm (253) 582 - 2224 (Inside Sounders Lanes) Sat - Mon CLOSED www.JBLMLTS.com Tickets are based on availability and reservations may be required. Prices are current as of 15 JUNE 2019 and are subject to change. Disneyland Military Salute 2019 *Valid January 1 - December 21, 2019* 3 Day Park Hopper (3+ years) $175.00 3 Day Park Hopper with Max Pass (3+ years)** $219.00 Expires 12/21/2019 4 Day Park Hopper (3+ years) $194.00 4 Day Park Hopper with Max Pass (3+ years)** $253.00 U.S. Military Personnel ONLY - Active, Retired, Reserve, 100% Disabled Vet, Commissioned Corps of Public Health Service and the Commissioned Corps of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on active duty can purchase tickets for themselves and up to five additional family members or friends. S ponsor or spouse must accompany ticket holders. Unaccompanied dependent children are not eligible to purchase these tickets. No more than six Salute tickets may be purchased by any eligible sponsor under this offer. Days can be used non - consecutively. Non-transferable. **WHAT IS MAX PASS?** Save time in line at popular attractions and entertainment by making FASTPASS selections through the Disneyland App while in the parks. FAST PASS just got faster! Capture all your memories with unlimited PHOTO PASS downloads from the day. -

Military Law Review

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET 27-1 00-21 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Articles KIDNAPPISG AS A 1IIILITARY OFFENSE Major hfelburn N. washburn RELA TI OX S HIP BETTYEE?; A4PPOISTED AND INDI T’IDUAL DEFENSE COUNSEL Lievtenant Commander James D. Nrilder COI~1KTATIONOF SIILITARY SENTENCES Milton G. Gershenson LEGAL ASPECTS OF MILITARY OPERATIONS IN COUNTERINSURGENCY Major Joseph B. Kelly SWISS MILITARY JUSTICE Rene‘ Depierre Comments 1NTERROC;ATION UNDER THE 1949 PRISOKERS OF TT-AR CON-EKTIO?; ONE HLSDREClTH ANNIS’ERSARY OF THE LIEBER CODE HEA,DQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 1963 PREFACE The Milita.ry Law Review is designed to provide a medium for those interested in the field of military law to share the product of their experience and research with their fellow lawyers. Articles should be of direct concern and import in this area of scholarship, and preference will be given to those articles having lasting value as reference material for the military lawyer. The Jli7itm~Law Review does not purport tg promulgate Depart- ment of the Army policy or to be in any sense directory. The opinions reflected in each article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Judge Advocate General or the Department of the Army. Articles, comments, and notes should be submitted in duplicate, triple spnced, to the Editor, MiZitary Law Review. The Judge Advo- cate General’s School, US. Army, Charlottewille, Virginia. Foot- notes should be triple spaced, set out on pages separate from the text and follow the manner of citation in the Harvard Blue Rook.