The Great Reviser; Or the Unknown Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HIGH MORLAGGAN PROJECT the History and Excavation of A

THE HIGH MORLAGGAN PROJECT The History and Excavation of a Deserted Highland Settlement Contents page 1. Introduction 1 1.1 The Project Circumstances 1 1.2 The High Morlaggan Project: Shadow People 1 2. Location and Topography 2 3. Historical and Archaeological Evidence 3 3.1. The History of High Morlaggan 4 3.2. Survey Results 19 3.3 Excavation Results 25 3.4 The Artefacts 31 4 Conclusion 35 References 36 Kilmartin House Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 [email protected] Scottish Charity SC022744 1. Introduction 1.1 The Project Circumstances This publication has been prepared by Kilmartin House Museum for the High Morlaggan Project, its aim to collate all the information from historical study and a programme of survey and excavation on the deserted settlement of High Morlaggan. The aims of the project are more fully outlined within the Project Design (Regan 2009) and a technical report of the excavation appears in the Data Structure Report (Regan 2010). Permission to carry out the survey and excavation of the site was granted by Luss Estates (the current owner). Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park Authority and Scottish Natural Heritage funded the project. 1.2 The High Morlaggan Project: Shadow People – Our Community‟s Heritage The High Morlaggan Project is a programme of research and events, that seeks to enhance the understanding and promotion of archaeology in the area. The archaeological excavation in particular was also an opportunity for the local community to get involved in the archaeological process. Engaging the public will raise awareness and build an appreciation of the area‟s archaeology and history. -

Walter Scott's Kelso

Walter Scott’s Kelso The Untold Story Published by Kelso and District Amenity Society. Heritage Walk Design by Icon Publications Ltd. Printed by Kelso Graphics. Cover © 2005 from a painting by Margaret Peach. & Maps Walter Scott’s Kelso Fifteen summers in the Borders Scott and Kelso, 1773–1827 The Kelso inheritance which Scott sold The Border Minstrelsy connection Scott’s friends and relations & the Ballantyne Family The destruction of Scott’s memories KELSO & DISTRICT AMENITY SOCIETY Text & photographs by David Kilpatrick Cover & illustrations by Margaret Peach IR WALTER SCOTT’s connection with Kelso is more important than popular histories and guide books lead you to believe. SScott’s signature can be found on the deeds of properties along the Mayfield, Hempsford and Rosebank river frontage, in transactions from the late 1790s to the early 1800s. Scott’s letters and journal, and the biography written by his son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart, contain all the information we need to learn about Scott’s family links with Kelso. Visiting the Borders, you might believe that Scott ‘belongs’ entirely to Galashiels, Melrose and Selkirk. His connection with Kelso has been played down for almost 200 years. Kelso’s Scott is the young, brilliant, genuinely unknown Walter who discovered Border ballads and wrote the Minstrelsy, not the ‘Great Unknown’ literary baronet who exhausted his phenomenal energy 30 years later saving Abbotsford from ruin. Guide books often say that Scott spent a single summer convalescing in the town, or limit references to his stays at Sandyknowe Farm near Smailholm Tower. The impression given is of a brief acquaintance in childhood. -

Lockhart'smemoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 16 2012 WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mulderig, Gerald P. (2012) "WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 38: Iss. 1, 119–138. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol38/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART’S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig “[W]hat can the best character in any novel ever be, compared to a full- length of the reality of genius?” asked John Gibson Lockhart in his 1831 review of John Wilson Croker’s edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson.1 Like many of his contemporaries in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lockhart regarded Boswell’s dramatic recreation of domestic scenes as an intrusive and doubtfully appropriate advance in biographical method, but also like his contemporaries, he could not resist a biography that opened a window on what he described with Wordsworthian ardor as “that rare order of beings, the rarest, the most influential of all, whose mere genius entitles and enables them to act as great independent controlling powers upon the general tone of thought and feeling of their kind” (ibid.). -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

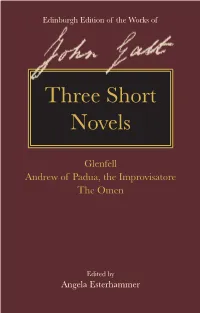

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse of Materiality in the Anglophone Periphery Joseph Rezek, Boston University A Paper Submitted to “Ireland, America, and the Worlds of Mathew Carey” Co-Sponsored by: The McNeil Center for Early American Studies The Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia, The University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia, PA October 27-29, 2011 *Please do not cite without permission of the author 2 British and American literary publishing were not separate affairs in the early nineteenth century. The transnational circulation of texts, fueled by readerly demand on both sides of the Atlantic; a reprint trade unregulated by copyright law and active, also, on both sides of the Atlantic; and transatlantic publishing agreements at the highest level of literary production all suggest that, despite obvious national differences in culture and circumstance, authors and booksellers in Britain and the United States participated in a single literary field. This literary field cohered through linked publishing practices and a shared English-language literary heritage, although it was also marked by internal division and cultural inequalities. Recent scholarship in the history of books, reading, and the dissemination of texts has suggested that literary producers in Ireland, Scotland, and the United States occupied analogous positions as they nursed long- standing rivalries with England and depended on English publishers and readers for cultural legitimation. Nowhere is such rivalry and dependence more evident than in the career of the most popular author in the period, Walter Scott, whose books were printed in Edinburgh but distributed mostly in London, where they reached their largest and most lucrative audience. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

Irresolute Ravishers and the Sexual Economy of Chivalry in the Romantic Novel

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU English Faculty Publications English Department 12-1-2000 Irresolute Ravishers and the Sexual Economy of Chivalry in the Romantic Novel Gary Dyer Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cleng_facpub Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement Article originally published as Dyer, Gary, "Irresolute Ravishers and the Sexual Economy of Chivalry in the Romantic Novel," Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Dec 2000): 340-68. © 2000 by The University of California Press. Recommended Citation Dyer, Gary, "Irresolute Ravishers and the Sexual Economy of Chivalry in the Romantic Novel" (2000). English Faculty Publications. 26. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cleng_facpub/26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Irresolute Ravishersand the Sexual Economy of Chivalryin the Romantic Novel GARY DYER - HZT theclimax ofJames Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans (1826) the American Indian Magua, findinghimself unable to kill his cap- tiveCora Munro as he has threatened,looks at her witha facial expression "in which conflictingpassions fiercelycontended." ' The situationhere evokes the climax of Walter Scott's Ivanhoe, published seven years earlier, in which Rebecca is saved from being burned at the stake when the villain Brian de Bois- Guilbert abruptlyfalls dead, overcome by "the violence of his own contending passions."2 In this essay I explore how these historical novels from the Romantic period attempt to deal withthe problems attendanton the chivalrousdesire to defend women-chivalry that ultimately becomes inconsequential, Nineteenth-CenturyLiterature, Vol. -

Twilight of the Godless: the Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle

Twilight of the Godless: The Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle WILLIAM CHRISTIE Edin r 13 Feb y 1830 My Dear Carlyle I am glad you think my regard for you a Mystery - as I am aware that must be its highest recommendation - I take it in an humbler sense - and am content to think it natural that one man of a kind heart should feel attracted towards another - and that a signal purity and loftiness of character, joined to great talents and something of a romantic history, should excite interest and respect. (NLS MS. 787, ff. 52-3) i I The Thomas Carlyle who knocked on Francis Jeffrey’s door at 92 George Street Edinburgh early in February of 1827 was not a young man. He was thirty two. And though Carlyle was of humble, country origins — he was the child of a rural stonemason turned small farmer — this was by no means his first time in the big city, having come here as a university student eighteen years before in 1809. Carlyle at thirty two, however, was as yet comparatively unknown, if not unpublished. His major publications — a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1824) and a Life of Schiller (1825) — had not brought his name before the English speaking reading public, probably because German thought and German literature simply did not interest them enough. Thomas Carlyle was an ambitious man and never doubted his own ability, but he must at this time have doubted his chances of success, and he had just added a young wife, Jane Welsh Carlyle, to his responsibilities. -

Redgauntlet, the Strategy of Oppositions, and the Logic of Compromise

Master’s Degree in European, American, and Postcolonial Languages and Literatures (ex D.M. 270/2004) Final Thesis Redgauntlet, The Strategy of Oppositions, and the Logic of Compromise Supervisor Ch. Prof. Enrica Villari Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Michela Vanon Alliata Graduand Giulia De Stefano Matricolation number 856036 Academic Year 2019 / 2020 To the memory of Pegah Naddafi, dear friend and colleague, to whom I will always be grateful. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. STRUCTURE: FACTS AND FICTION I.1 The Eclectic Structure of Redgauntlet……….…………………….………………. pp. 3-9 I.1.1 The Embedded Stories in Redgauntlet………………………………………… pp. 4-7 I.1.2 Interpolations: From First-Person to Third-Person Narrative…………………. pp. 7-9 I.2 Lawyers and Storytellers………………………………………………………….. pp. 9-23 I.2.1 Scott’s Autobiographical Echoes in Redgauntlet…………..…………………... pp. 10-14 I.2.2 Fiction as a Case: Alan Fairford, the Lawyer………..………………………… pp. 15-18 I.2.3 Fiction as a Romantic Adventure: Darsie’s Letters……...………..………….... pp. 18- 23 I.3 Facts and Fiction: The Metafictional Implications in Redgauntlet’s Structure… pp. 23-30 II. EVENTS: REALITY AND THE SUPERNATURAL II.1 Wandering Willie’s Tale: An Example of Balance between Supernatural and Historical…………………………………………………………………………………pp. 32-45 II.1.1 The Inspiration and Plot of the Tale……………………………………………. pp. 32-37 II.1.2 The Unsolvable Ambiguity of the Tale and Scott’s Technique………………....pp. 37-42 II.1.3 The Function of the Tale in Redgauntlet………………………………….……..pp. 42-45 II.2 The Future of the Redgauntlets: Fate or History?..................................................pp. 45-60 II.2.1 The Supernatural Explanation: The Family’s Curse……………….……………pp. -

Walter Scott, James Hogg and Uncanny Testimony: Questions of Evidence and Authority Deirdre A

Walter Scott, James Hogg and Uncanny Testimony: Questions of Evidence and Authority Deirdre A. M. Shepherd PhD – The University of Edinburgh – 2009 Contents Preface i Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Opening the Debate, 1790-1810 1 1.1 Walter Scott, James Hogg and Literary Friendship 8 1.2 The Uncanny 10 1.3 The Supernatural in Scotland 14 1.4 The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, 1802-3, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, 1805, and The Mountain Bard, 1807 20 1.5 Testimony, Evidence and Authority 32 Chapter Two: Experimental Hogg: Exploring the Field, 1810-1820 42 2.1 The Highlands and Hogg: literary apprentice 42 2.2 Nineteenth-Century Edinburgh: ‘Improvement’, Periodicals and ‘Polite’ Culture 52 2.3 The Spy, 1810 –1811 57 2.4 The Brownie of Bodsbeck, 1818 62 2.5 Winter Evening Tales, 1820 72 Chapter Three: Scott and the Novel, 1810-1820 82 3.1 Before Novels: Poetry and the Supernatural 82 3.2 Second Sight and Waverley, 1814 88 3.3 Astrology and Witchcraft in Guy Mannering, 1815 97 3.4 Prophecy and The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819 108 Chapter Four: Medieval Material, 1819-1822 119 4.1 The Medieval Supernatural: Politics, Religion and Magic 119 4.2 Ivanhoe, 1820 126 4.3 The Monastery, 1820 135 4.4 The Three Perils of Man, 1822 140 Chapter Five: Writing and Authority, 1822-1830 149 5.1 Divinity Matters: Election and the Supernatural 149 5.2 Redgauntlet, 1824 154 5.3 The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, 1824 163 Chapter Six: Scott: Reviewing the Fragments of Belief, 1824-1830 174 6.1 In Pursuit of the Supernatural 174 6.2 ‘My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror’ and ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ in The Keepsake, 1828 178 6.3 Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, addressed to J.