Redgauntlet, the Strategy of Oppositions, and the Logic of Compromise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Johnstones, 1191-1909, with Descriptions of Border Life

SECRETARY JOHNSTON 161 service. In 171 1 a Custom House official wrote to his superior in Edinburgh, " that in Ruthwell the people are such friends to the traffic, no one can be found to lodge a Government officer for the night." April 17, 1717, was appointed as a day of solemn fasting to avert the intended invasion of an enemy, and the threatened scarcity of bread- generally made of rye or oatmeal—owing to the severity of the weather. In 1720 we find a complaint at the meeting of the Presbytery that the Kirk was losing its power over the people, swearing—so far as the expressions in a theatre was opened "faith" and "devil" were sometimes heard ; and 1729 in Edinburgh. A minister wa3 suspended for attending it. The Scots were notably a charitable people, and, though the population of Scotland was but a million and a quarter, they supported a vagrant population 1 of 200,000 early in the eighteenth century, besides licensed bedesmen. In better times there were periodical offertories in the Churches for the benefit of seamen enslaved by the Turkish and Barbary Corsairs in the Mediterranean, in the galleys others who had their tongues cut out or been otherwise crippled ; were still in need of ransom. But the epidemics carried about by the vagrants, the dearness of provisions, added to the abolition of the Scottish Parliament, sent many landowners, particularly on the Borders, to live in England. The in and it new Marquis of Annandale began to spend most of his time London ; was on the " parlour door of his lodgings in the Abbey " of Westminster that Robert Allane, Sheriff's messenger of Annan, knocked the six knocks and affixed the document showing that he had been put to the horn, because, as Provost of Annan, he had taken no steps to arrest Galabank for debt—the application having been made by Mr Patrick Inglis, the deposed Episcopalian minister of Annan. -

Lockhart'smemoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 16 2012 WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mulderig, Gerald P. (2012) "WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 38: Iss. 1, 119–138. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol38/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART’S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig “[W]hat can the best character in any novel ever be, compared to a full- length of the reality of genius?” asked John Gibson Lockhart in his 1831 review of John Wilson Croker’s edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson.1 Like many of his contemporaries in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lockhart regarded Boswell’s dramatic recreation of domestic scenes as an intrusive and doubtfully appropriate advance in biographical method, but also like his contemporaries, he could not resist a biography that opened a window on what he described with Wordsworthian ardor as “that rare order of beings, the rarest, the most influential of all, whose mere genius entitles and enables them to act as great independent controlling powers upon the general tone of thought and feeling of their kind” (ibid.). -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

Authors, Translators & Other Masqueraders

Transgressing Authority – Authors, Translators and Other Masqueraders Alexandra Lopes The huge success of Walter Scott in Portugal in the first half of the 19th century was partially achieved by sacrificing the ironic take on authorship his Waverley Novels entailed. This article examines translations of his works within the context of 19th century Portugal with a focus on the translation(s) of Waverley. The briefest perusal of the Portuguese texts reveals plentiful instances of new textual authority, which naturally compose a sometimes very different author(ship) -- an authorship often mediated by French translations. Thus a complex web of authority emerges effectively, if deviously, (re)creating the polyphony of authorial voices and the displacement of the empirical author first staged by the source texts themselves. Keywords: authorship, literary translation, translation history, translatability L’immense succès connu par Walter Scott au Portugal dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle se doit en partie au sacrifice de la dimension ironique de la voix auctoriale dans sa série Waverley. Cet article examine les traductions des oeuvres de Scott dans le contexte du Portugal de l’époque en portant une attention particulière aux traductions de Waverley. Même un très bref aperçu des textes portuguais révèle de nombreux exemples d’instances nouvelles d’autorité narrative, lesquelles créent une voix auctoriale parfois très différente de celle du texte original à cause souvent du rôle médiateur des traductions françaises. Un tissu complexe de voix auctoriales émerge ainsi, bien que par le biais d’artifices, recréant la polyphonie des voix auctoriales et le déplacement de l’auteur empirique, mis en scène d’abord par les textes originaux. -

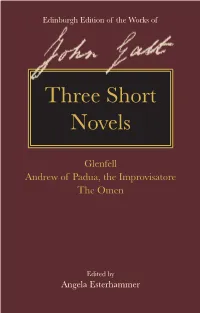

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Dumfries and Galloway Described by Macgibbon and Ross 1887–92: What Has Become of Them Since? by Janet Brennan-Inglis

TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY FOUNDED 20 NOVEMBER 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME 88 LXXXVIII Editors: ELAINE KENNEDY FRANCIS TOOLIS JAMES FOSTER ISSN 0141-12 2014 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2013–2014 and Fellows of the Society President Mr L. Murray Vice-Presidents Mrs C. Iglehart, Mr A. Pallister, Mrs P.G. Williams and Mr D. Rose Fellows of the Society Mr A.D. Anderson, Mr J.H.D. Gair, Dr J.B. Wilson, Mr K.H. Dobie, Mrs E. Toolis, Dr D.F. Devereux, Mrs M. Williams and Dr F. Toolis Mr L.J. Masters and Mr R.H. McEwen — appointed under Rule 10 Hon. Secretary Mr J.L. Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H. Barrington, 30 Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr M. Cook, Gowanfoot, Robertland, Amisfield, Dumfries DG1 3PB Hon. Librarian Mr R. Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Hon. Institutional Subscriptions Secretary Mrs A. Weighill Hon. Editors Mrs E. Kennedy, Nether Carruchan, Troqueer, Dumfries DG2 8LY Dr F. Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Dr J. Foster (Webmaster), 21 Maxwell Street, Dumfries DG2 7AP Hon. Syllabus Conveners Mrs J. Brann, Troston, New Abbey, Dumfries DG2 8EF Miss S. Ratchford, Tadorna, Hollands Farm Road, Caerlaverock, Dumfries DG1 4RS Hon. Curators Mrs J. Turner and Miss S. Ratchford Hon. Outings Organiser Mrs S. Honey Ordinary Members Mr R. Copland, Dr Jeanette Brock, Dr Jeremy Brock, Mr D. Scott, Mr J. McKinnell, Mr A. Gair, Mr D. Dutton CONTENTS Herbarium of Matthew Jamieson by David Hawker .............................................. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

Some Thoughts on Quakers in Scotland During the Last Half Century

'STANDS SCOTLAND WHERE IT DID?' SOME THOUGHTS ON QUAKERS IN SCOTLAND DURING THE LAST HALF CENTURY think I first heard the word Quaker from my father. It was in rather curious circumstances. I can have been only five or six years old, I but I have a very clear picture of him, jogging around the small parlour in the manse in Lochgelly in a sort of shuffle as he intoned the words (one could scarcely call it singing): Merrily danced the Quaker's wife, Merrily danced the Quaker. I had no idea of the significance of the words, and I do not know what they meant to my father. Only many years later was I to learn that the tune and the words were traditional and that Robert Burns, that great authority on the folk music of Scotland, had written to the tune what he thought was 'one of the finest songs I ever made in my life', but the wore s, the catchy tune and my father's enthusiasm stirred my youthful interest and I had an immediate and lasting impression of Quakers as happy joyful people. Then some two years later when I was beginning piano lessons with the church organist you can imagine my pleasure when I found in my Hemy's Tutor that one of my first practice pieces was 'Merrily danced the Quaker'. The first Quaker I met I came across perhaps five or six years later in the pages of Sir Walter Scott's novel, Redgauntlet. I would not have you think that I was reading the Waverley novels, complete and unabridged, when I was ten or twelve years old, even though I had a father and an uncle who were devoted admirers of the novelist. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer 'Earth and Stone' Citation for published version: Fielding, P 2018, 'Earth and Stone': Improvement, entailment, and geographical futures in the novel of the 1820s. in A Benchimol & G McKeever (eds), Cultures of Improvement in Scottish Romanticism, 1707-1840. The Enlightenment World: Political and Intellectual History of the Long Eighteenth Century, Routledge, pp. 152-169. https://doi.org/20.500.11820/0cea5533-5c64-41a4-9abc-ffdfef6de823 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 20.500.11820/0cea5533-5c64-41a4-9abc-ffdfef6de823 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Cultures of Improvement in Scottish Romanticism, 1707-1840 Publisher Rights Statement: "This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in "Cultures of Improvement in Scottish Romanticism, 1707-1840" on 11/4/2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Cultures-of- Improvement-in-Scottish-Romanticism-1707-1840/Benchimol-McKeever/p/book/9781138482937. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Download Redgauntlet

Redgauntlet by Sir Walter Scott Redgauntlet by Sir Walter Scott * REDGAUNTLET by Sir Walter Scott, Bart. * CONTENTS. Introduction Text Letters I - XIII Chapters I - XXIII Conclusion Notes Glossary * page 1 / 806 Note: Footnotes in the printed book have been inserted in the etext in square brackets ("[]") close to the place where they were referenced by a suffix in the original text. Text in italics has been written in capital letters. There are some numbered notes at the end of the text that are referred to by their numbers with brief notes, also in square brackets, embedded in the text. * INTRODUCTION The Jacobite enthusiasm of the eighteenth century, particularly during the rebellion of 1745, afforded a theme, perhaps the finest that could be selected for fictitious composition, founded upon real or probable incident. This civil war and its remarkable events were remembered by the existing generation without any degree of the bitterness of spirit which seldom fails to attend internal dissension. The Highlanders, who formed the principal strength of Charles Edward's army, were an ancient and high-spirited race, peculiar in their habits of war and of peace, brave to romance, and exhibiting a character turning upon points more adapted to poetry than to the prose of real life. Their prince, young, valiant, patient of fatigue, and despising danger, heading his army on foot in the most toilsome marches, and page 2 / 806 defeating a regular force in three battles--all these were circumstances fascinating to the imagination, and might well be supposed to seduce young and enthusiastic minds to the cause in which they were found united, although wisdom and reason frowned upon the enterprise. -

Twilight of the Godless: the Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle

Twilight of the Godless: The Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle WILLIAM CHRISTIE Edin r 13 Feb y 1830 My Dear Carlyle I am glad you think my regard for you a Mystery - as I am aware that must be its highest recommendation - I take it in an humbler sense - and am content to think it natural that one man of a kind heart should feel attracted towards another - and that a signal purity and loftiness of character, joined to great talents and something of a romantic history, should excite interest and respect. (NLS MS. 787, ff. 52-3) i I The Thomas Carlyle who knocked on Francis Jeffrey’s door at 92 George Street Edinburgh early in February of 1827 was not a young man. He was thirty two. And though Carlyle was of humble, country origins — he was the child of a rural stonemason turned small farmer — this was by no means his first time in the big city, having come here as a university student eighteen years before in 1809. Carlyle at thirty two, however, was as yet comparatively unknown, if not unpublished. His major publications — a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1824) and a Life of Schiller (1825) — had not brought his name before the English speaking reading public, probably because German thought and German literature simply did not interest them enough. Thomas Carlyle was an ambitious man and never doubted his own ability, but he must at this time have doubted his chances of success, and he had just added a young wife, Jane Welsh Carlyle, to his responsibilities. -

The Author of Waverley, with His Various Personas, Is a Highly

Promoting Saint Ronans Well: Scotts Fiction and Scottish Community in Transition MATSUI Yuko The Author of Waverley, with his various personas, is a highly sociable and com- municative writer, as we observe in the frequent and lively exchanges between the author and his reader or characters in the conclusions of Old Mortality1816 and Redgauntlet1824 , or in the prefaces to The Abbot1820 and The Betrothed1825 , to give only a few examples. Walter Scott himself, after giving up his anonymity, seems to enjoy an intimate author-reader relationship in his prefaces and notes to the Magnum Opus edition. Meanwhile, Scott often adapts and combines more than one historical event or actual person, his sources or originals, in his attempt to recre- ate the life of a particular historical period and give historical sense to it, as books like W. S. Crocketts The Scott Originals1912 eloquently testify, and with the Porteous Riot and Helen Walker in The Heart of Midlothian1818 as one of the most obvious examples. Both of these characteristics often tend to encourage an active interaction between the real and the imagined, or their confluence, within and outwith Scott's historical fiction, perhaps most clearly shown in the development of tourism in 19th century Scotland1. In the case of Saint Ronan’s Well1824 [1823], Scotts only novel set in the 19th century, its contemporaneity seems to have allowed that kind of interaction and confluence to take its own vigorous form, sometimes involving an actual commu- nity or other authors of contemporary Scotland. Thus, we would like to examine here the ways in which Scott adapts his sources to explore his usual interest in historical change in this contemporary fiction and how it was received, particularly in terms of its effect on a local community in Scotland and in terms of its inspiration for his fellow authors, and thus reconsider the part played by Scotts fiction in imagining and pro- moting Scotland in several ways, in present and past Scotland.