Lockhart'smemoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

Walter Scott's Kelso

Walter Scott’s Kelso The Untold Story Published by Kelso and District Amenity Society. Heritage Walk Design by Icon Publications Ltd. Printed by Kelso Graphics. Cover © 2005 from a painting by Margaret Peach. & Maps Walter Scott’s Kelso Fifteen summers in the Borders Scott and Kelso, 1773–1827 The Kelso inheritance which Scott sold The Border Minstrelsy connection Scott’s friends and relations & the Ballantyne Family The destruction of Scott’s memories KELSO & DISTRICT AMENITY SOCIETY Text & photographs by David Kilpatrick Cover & illustrations by Margaret Peach IR WALTER SCOTT’s connection with Kelso is more important than popular histories and guide books lead you to believe. SScott’s signature can be found on the deeds of properties along the Mayfield, Hempsford and Rosebank river frontage, in transactions from the late 1790s to the early 1800s. Scott’s letters and journal, and the biography written by his son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart, contain all the information we need to learn about Scott’s family links with Kelso. Visiting the Borders, you might believe that Scott ‘belongs’ entirely to Galashiels, Melrose and Selkirk. His connection with Kelso has been played down for almost 200 years. Kelso’s Scott is the young, brilliant, genuinely unknown Walter who discovered Border ballads and wrote the Minstrelsy, not the ‘Great Unknown’ literary baronet who exhausted his phenomenal energy 30 years later saving Abbotsford from ruin. Guide books often say that Scott spent a single summer convalescing in the town, or limit references to his stays at Sandyknowe Farm near Smailholm Tower. The impression given is of a brief acquaintance in childhood. -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Joseph Ritson and the Publication of Early English Literature Genevieve Theodora McNutt PhD in English Literature University of Edinburgh 2018 1 Declaration This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Portions of the final chapter have been published, in a condensed form, as a journal article: ‘“Dignified sensibility and friendly exertion”: Joseph Ritson and George Ellis’s Metrical Romance(ë)s.’ Romantik: Journal for the Study of Romanticisms 5.1 (2016): 87-109. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/rom.v5i1.26422. Genevieve Theodora McNutt 2 3 Abstract This thesis examines the work of antiquary and scholar Joseph Ritson (1752-1803) in publishing significant and influential collections of early English and Scottish literature, including the first collection of medieval romance, by going beyond the biographical approaches to Ritson’s work typical of nineteenth- and twentieth- century accounts, incorporating an analysis of Ritson’s contributions to specific fields into a study of the context which made his work possible. -

Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

* a MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. BY J. G. LOCKHART VOL. II. BOSTON: V OTIS, BROADERS, AND COMPANY. 1837 CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME CHAPTER I. Page. Contributions to the Edinburgh Review—Progress of the Tristrem—and of the of the Last Minstrel—Visit of Wordsworth—Publication of " Lay Sir Tristrem."—1803-1804, 1 CHAPTER II. Removal to Ashestiel—Death of Captain Robert Scott—Mungo Park— Completion and Publication of the Lay of the Last Minstrel—1804-1805, 26 CHAPTER III. with — of Partnership James Ballantyne Literary Projects 5 Edition the British Poets Edition of the ; Ancient English Chronicles, &c. &c— Edition of Dryden undertaken—Earl Moira Commander of the Forces in Scotland—Sham Battles—Articles in the Edinburgh Review—Com- mencement of Waverley—Letter on Ossian—Mr. Skene's Reminis- cences of Ashestiel—Excursion to Cumberland—Alarm of Invasion— Visit of Mr. Southey—Correspondence on Dryden with Ellis and Words- worth— 180o ; 54 CHAPTER IV. Affair of the Clerkship of Session—Letters to Ellis and Lord Dalkeith— Visit to London—Earl Spencer and Mr. Fox—Caroline, Princess of Wales—Joanna Baillie—Appointment as Clerk of Session—Lord Mel- ville's Trial—Song on his Acquittal—1806, 86 CHAPTER V. Dryden—Critical Pieces—Edition of Slingsby's Memoirs, &c.—Mar'mion begun—Visit to London—Ellis—Rose—Canning—Miss Seward—Scott Secretary to the Commission on Scotch Jurisprudence—Letters to Southey, &c.—Publication of Marmion—Anecdotes—The Edinburgh Review on Marmion—1806-1808, 107 CHAPTER VI. Edition of Dryden published—And criticised by Mr. Hallam—Weber's —Editions of Carleton's Memoirs Romances Quecnlioo-hall ; Captain ; of Robert Earl of The Sadler The Memoirs Cary, Monmouth ; Papers 3 and the Somers' Tracts—Edition of Swift begun—Letters to Joanna Baillie and George Ellis on the affairs of the Peninsula—John Struthers —James Hogg— Visit of Mr. -

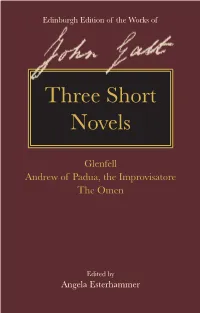

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse of Materiality in the Anglophone Periphery Joseph Rezek, Boston University A Paper Submitted to “Ireland, America, and the Worlds of Mathew Carey” Co-Sponsored by: The McNeil Center for Early American Studies The Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia, The University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia, PA October 27-29, 2011 *Please do not cite without permission of the author 2 British and American literary publishing were not separate affairs in the early nineteenth century. The transnational circulation of texts, fueled by readerly demand on both sides of the Atlantic; a reprint trade unregulated by copyright law and active, also, on both sides of the Atlantic; and transatlantic publishing agreements at the highest level of literary production all suggest that, despite obvious national differences in culture and circumstance, authors and booksellers in Britain and the United States participated in a single literary field. This literary field cohered through linked publishing practices and a shared English-language literary heritage, although it was also marked by internal division and cultural inequalities. Recent scholarship in the history of books, reading, and the dissemination of texts has suggested that literary producers in Ireland, Scotland, and the United States occupied analogous positions as they nursed long- standing rivalries with England and depended on English publishers and readers for cultural legitimation. Nowhere is such rivalry and dependence more evident than in the career of the most popular author in the period, Walter Scott, whose books were printed in Edinburgh but distributed mostly in London, where they reached their largest and most lucrative audience. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

1 4 Henry Stead Swinish Classics

Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). 4 Henry Stead Swinish classics; or a conservative clash with Cockney culture On 1 November 1790 Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France was published in England. The counter-revolutionary intervention of a Whig politician who had previously championed numerous progressive causes provided an important rallying point for traditionalist thinkers by expressing in plain language their concerns 1 Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). about the social upheaval across the channel. From the viewpoint of pro- revolutionaries, Burke’s Reflections gave shape to the conservative forces they were up against; its publication provoked a ‘pamphlet war’, which included such key radical responses to the Reflections as Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790) and Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man (1791).1 In Burke’s treatise, he expressed a concern for the fate of French civilisation and its culture, and in so doing coined a term that would haunt his counter-revolutionary campaign. Capping his deliberation about what would happen to French civilisation following the overthrow of its nobility and clergy, which he viewed as the twin guardians of European culture, he wrote, ‘learning will be cast into the mire, and trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude’. This chapter asks what part the Greek and Roman classics played in the cultural war between British reformists and conservatives in the periodical press of the late 1810s and early 1820s. -

The Arthurian Legend in British Women's Writing, 1775–1845

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research @ Cardiff Avalon Recovered: The Arthurian Legend in British Women’s Writing, 1775–1845 Katie Louise Garner B.A. (Cardiff); M.A. (Cardiff) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University September 2012 Declaration This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… Acknowledgements First thanks are due to my supervisors, Jane Moore and Becky Munford, for their unceasing assistance, intellectual generosity, and support throughout my doctoral studies. -

1831 SIR WALTER SCOTT 1 (March 1831 Continued)

1831 SIR WALTER SCOTT 1 (March 1831 continued) TO THE REV. ALEXANDER DYCE,1 LONDON [Extract] (12-1)ABBOTSFORD, March 31, 1831 (12-1)DEAR SIR,—I had the pleasure of receiving Greene's (12-1)Plays, with which, as works of great curiosity, I am highly (12-1)gratified. If the editor of the Quarterly consents, as he (12-1)probably will, I shall do my endeavour to be useful, (12-1)though I am not sure when I can get admission. I shall (12-1)be inclined to include Webster, who, I think, is one of the (12-1)best of our ancient dramatists ; if you will have the kindness (12-1)to tell the bookseller to send it to Whittaker, under cover (12-1)to me, care of Mr Cadell, Edinburgh, it will come safe, and (12-1)be thankfully received. Marlowe and others I have,—and (12-1)some acquaintance with the subject, though not much... .2 (12-1)I wish you had given us more of Greene's prose works.— (12-1)I am, with regard, dear sir, yours sincerely, (12-1)[Lockhart] WALTER SCOTT 2 LETTERS OF 1831 TO ROBERT CADELL (12-2)MY DEAR SIR,—I return Southennan 1 three volumes. (12-2)I should like much to have a reading of Waterwitch. (12-2)Some confusion in returning the Sheets between Ballantyne (12-2)& me have hankd the tail of the Tales. It is now (12-2)free. As I do not wish to fail in the Count I am determind (12-2)not to spare reading on Count Robert & am labouring (12-2)through the Byzantine historians. -

Scholars Retelling Romances 'N 15 of ~H Th, Ie H I, Phiilipa Hardman

Scholars Retelling Romances 'n 15 Of ~h th, Ie h i, Phiilipa Hardman . ke niversity of Readtng II :0 le It would be a very interesting experiment to ask a group of scholars to write a short account of some striking passage from a medieval romance, which could then be compared with the original. It is my bile belief that a significant proportion of those accounts would be lia, coloured here and there by touches of humour which were not present 'or in the original romance texts, This is a phenomenon which I have frequently noticed in listening to scholarly papers, reading articles and SUS books of criticism; even in preparing my own lectures to students - and it was this last discovery that led me to try to investigate further. Why is it that one finds examples of intrusive humour, whether intentional or involuntary, in the retelling or summarizing of medieval romances by scholars, Gfitics, and other readers, right through from the revival of interest in the romances in the late eighteenth century up to the present day? What is the significance of the fact that appreciative and serious readers of romance can respond to the texts in this way? As a preliminary example, I shall examine three different versions of the story of Arthur's conception and birth. The first comes from Joseph Ritson's pioneering work of scholarship, Ancient Eng/eish Metrical Romoncees,l an edition of twelve Middle English verse romances, prefaced by a lengthy, scholarly dissertation on the function and status of minstrels, and furnished with comparative notes.