Coastal Grass-Sedge Wetlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.07 Frogs and Wetlands

Chapter 2.7 — Frogs and wetlands • 161 2.7 Frogs and wetlands Dr Arthur White Biosphere Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd Australia Abstract Australian frogs are remarkably diverse in their life styles and their use of wetlands. Our understanding of the ecological needs of frogs is incomplete but we do know some of the major requirements for survival, such as the need for clean water, the need for safe foraging areas, the need for shelter from predators and adverse weather conditions, the need for minimal habitat stress (as this increases the susceptibility of frogs to disease). The design of wetlands must take into account these over-riding requirements, plus the specific requirements that are unique to each frog species. In this paper, I refer to the management of the Green and Golden Bell Frog during the establishment of the Sydney Olympic site as an example of sorts of considerations that are required in managing frogs and wetlands. Chapter 2.7 — Frogs and wetlands • 162 Australian Frogs 2. Air pollution: massive amounts of Sulphur Dioxide and Nitrogen Dioxide (and There are about 250 described frog species in other gases) have been released into the Australia (Anstis 2013). This is a surprisingly high atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. number of frog species for such an arid continent. These gases combine with moisture in the Australian frogs have had to adapt of the vagaries air and create toxic substances that kill frogs, of Australia’s climate and can survive in areas where other animals and plants. In the northern you would not expect them to be. -

Drivers for Decentralised Systems in South East Queensland

Drivers for Decentralised Systems in South East Queensland Grace Tjandraatmadja, Stephen Cook, Angel Ho, Ashok Sharma and Ted Gardner October 2009 Urban Water Security Research Alliance Technical Report No. 13 Urban Water Security Research Alliance Technical Report ISSN 1836-5566 (Online) Urban Water Security Research Alliance Technical Report ISSN 1836-5558 (Print) The Urban Water Security Research Alliance (UWSRA) is a $50 million partnership over five years between the Queensland Government, CSIRO’s Water for a Healthy Country Flagship, Griffith University and The University of Queensland. The Alliance has been formed to address South-East Queensland's emerging urban water issues with a focus on water security and recycling. The program will bring new research capacity to South-East Queensland tailored to tackling existing and anticipated future issues to inform the implementation of the Water Strategy. For more information about the: UWSRA - visit http://www.urbanwateralliance.org.au/ Queensland Government - visit http://www.qld.gov.au/ Water for a Healthy Country Flagship - visit www.csiro.au/org/HealthyCountry.html The University of Queensland - visit http://www.uq.edu.au/ Griffith University - visit http://www.griffith.edu.au/ Enquiries should be addressed to: The Urban Water Security Research Alliance PO Box 15087 CITY EAST QLD 4002 Ph: 07-3247 3005; Fax: 07-3405 3556 Email: [email protected] Ashok Sharma - Project Leader Decentralised Systems CSIRO Land and Water 37 Graham Road HIGHETT VIC 3190 Ph: 03-9252 6151 Email: [email protected] Citation: Grace Tjandraatmadja, Stephen Cook, Angel Ho, Ashok Sharma and Ted Gardner (2009). Drivers for Decentralised Systems in South East Queensland. -

Pimpama River Catchment Hydrological Study Addendum Report

Pimpama River Catchment Hydrological Study Addendum Report July 2015 Title: Pimpama River Catchment Hydrological Study - Addendum Report 2015 Author: Study for: City Planning Branch Planning and Environment Directorate The City of Gold Coast File Reference: WF18/44/02 (P3) TRACKS #50622520 Version history Changed by Reviewed by & Version Comments/Change & date date 1.0 Adoption of BOM’s new IFD 2013 2.0 Grammar Review Distribution list Name Title Directorate Branch NH Team PE City Planning TRACKS-#50622520-v3-PIMPAMA_RIVER_HYDROLOGICAL_STUDY_ADDENDUM_REPORT_JULY_2015 Page 2 of 26 1. Executive Summary The City of Gold Coast (City) undertook a hydrological study for Pimpama River catchment in December 2014 (City 2014, Ref 1). In the study, the Pimpama River catchment hydrological model was developed using the URBS modelling software. The model was calibrated to three historical flood events and verified against another four flood events. The design rainfalls from 2 to 2000 year annual recurrence intervals (ARIs) of the study were based on study undertaken by Australian Water Engineering (AWE) in 1998 and CRC-FORGE. In early 2015, the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) released new IFD (2013) design rainfalls as part of the revision of Engineers Australia’s design handbook ‘Australian Rainfall and Runoff: A Guide to Flood Estimation’. In July 2015, the 2014 calibrated Pimpama hydrological model was used to run the design events using rainfall data obtained from the BOM’s new 2013 IFD tables. This report documents the review of City 2014 model and should be read in conjunction with the City 2014 hydrological study report. The original forest factor, catchment and channel parameters obtained from the 2014 calibrated Pimpama hydrological model were used for this study update. -

North Central Waterwatch Frogs Field Guide

North Central Waterwatch Frogs Field Guide “This guide is an excellent publication. It strikes just the right balance, providing enough information in a format that is easy to use for identifying our locally occurring frogs, while still being attractive and interesting to read by people of all ages.” Rodney Orr, Bendigo Field Naturalists Club Inc. 1 The North Central CMA Region Swan Hill River Murray Kerang Cohuna Quambatook Loddon River Pyramid Hill Wycheproof Boort Loddon/Campaspe Echuca Watchem Irrigation Area Charlton Mitiamo Donald Rochester Avoca River Serpentine Avoca/Avon-Richardson Wedderburn Elmore Catchment Area Richardson River Bridgewater Campaspe River St Arnaud Marnoo Huntly Bendigo Avon River Bealiba Dunolly Loddon/Campaspe Dryland Area Heathcote Maryborough Castlemaine Avoca Loddon River Kyneton Lexton Clunes Daylesford Woodend Creswick Acknowledgement Of Country The North Central Catchment Management Authority (CMA) acknowledges Aboriginal Traditional Owners within the North Central CMA region, their rich culture and their spiritual connection to Country. We also recognise and acknowledge the contribution and interests of Aboriginal people and organisations in the management of land and natural resources. Acknowledgements North Central Waterwatch would like to acknowledge the contribution and support from the following organisations and individuals during the development of this publication: Britt Gregory from North Central CMA for her invaluable efforts in the production of this document, Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority for allowing use of their draft field guide, Lydia Fucsko, Adrian Martins, David Kleinert, Leigh Mitchell, Peter Robertson and Nick Layne for use of their wonderful photos and Mallee Catchment Management Authority for their design support and a special thanks to Ray Draper for his support and guidance in the development of the Frogs Field Guide 2012. -

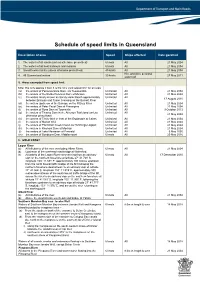

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

Predation by Introduced Cats Felis Catus on Australian Frogs: Compilation of Species Records and Estimation of Numbers Killed

Predation by introduced cats Felis catus on Australian frogs: compilation of species records and estimation of numbers killed J. C. Z. WoinarskiA,M, S. M. LeggeB,C, L. A. WoolleyA,L, R. PalmerD, C. R. DickmanE, J. AugusteynF, T. S. DohertyG, G. EdwardsH, H. GeyleA, H. McGregorI, J. RileyJ, J. TurpinK and B. P. MurphyA ANESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia. BNESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Research, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Qld 4072, Australia. CFenner School of the Environment and Society, Linnaeus Way, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2602, Australia. DWestern Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Bentley, WA 6983, Australia. ENESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Desert Ecology Research Group, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. FQueensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Red Hill, Qld 4701, Australia. GCentre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences (Burwood campus), Deakin University, Geelong, Vic. 3216, Australia. HNorthern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, PO Box 1120, Alice Springs, NT 0871, Australia. INESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, School of Biological Sciences, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tas. 7001, Australia. JSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, United Kingdom. KDepartment of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, 49 Kew Street, Welshpool, WA 6106, Australia. LPresent address: WWF-Australia, 3 Broome Lotteries House, Cable Beach Road, Broome, WA 6276, Australia. MCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1. Data sources used in compilation of cat predation on frogs. -

Australasian Bulletin of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Chemistry

ABEEC New Cover 2015.pdf 1 23/07/2015 4:24:53 PM A a ustralasi Australasian Bulletin of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Chemistry The Ocial Bulletin of the Australasian Chapter of the Volume 2, 2015 Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry Asia Pacific C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 1 AUSTRALASIAN BULLETIN OF ecOTOXICOLOGY & ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMISTRY Editor-in-Chief Dr Reinier Mann, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, GPO Box 2454, Brisbane Qld 4000, Australia. email: [email protected]. Associate Editor Dr Anne Colville, Centre for Environmental Sustainability, University of Technology, Sydney, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia. email: [email protected]. Call for Papers The Bulletin welcomes Original Research Papers, Short Communications, Review Papers, Commentaries and Letters to the Editors. Guidelines for Authors For information on Guidelines for Authors please contact the editors. AIMS AND SCOPE The Australasian Bulletin of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Chemistry is a publication of the Australasian Chapter of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry – Asia Pacific (a geographic unit of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry). It is dedicated to publishing scientifically sound research articles dealing with all aspects of ecotoxicology and environmental chemistry. All data must be generated by statistically and analytically sound research, and all papers will be peer reviewed by at least two reviewers prior to being considered for publication. The Bulletin will give priority to the publication of original research that is undertaken on the systems and organisms of the Australasian and Asia-Pacific region, but papers will be accepted from anywhere in the world. -

Mangrove Wetlands

WETLAND MANAGEMENT PROFILE MANGROVE WETLANDS Mangrove wetlands are characterised by Description trees that are uniquely adapted to tolerate Mangroves are woody plants, usually trees (woodland daily or intermittent inundation by the sea. to forest) but also shrubs, growing in the intertidal Distinctive animals are nurtured in their zone and able to withstand periods of inundation by sheltered waters and mazes of exposed seawater each day. In this profile, the term ”mangrove mangrove roots; others live in the underlying wetland” is used to refer to wetlands that are characterised by dominance of mangroves. mud. A familiar sight on the coast throughout “Mangrove associates” are non-woody plants that Queensland, mangrove wetlands provide mainly or commonly occur in mangrove wetlands. frontline defence against storm damage, The terms “mangrove forest” and “mangrove swamp” enhance reef water quality and sustain are sometimes used in regard to particular types of fishing and tourism industries. These habitat mangrove wetland or to mangrove wetland in general. assets can be preserved and loss and degradation (through pollution and changed MANGROVE wetlands are characterised water flows) averted by raising awareness of by the dominance of mangroves — woody the benefits of mangrove wetlands and by implementing integrated plans for land and plants growing in the intertidal zone and resource use in the coastal zone. able to withstand periods of inundation by seawater each day. Situated in land zone 1, mangrove wetlands are invariably in the intertidal zone and sometimes extend narrowly for many kilometres inland along tidal rivers, also around some near-shore islands. Accordingly, they are below the level of Highest Astronomical Tide (HAT) and typically are in the lower, most frequently and deeply inundated parts of the intertidal zone. -

South Coast District

152°30'E NORTH COAST DISTRICT 153°0'E METROPOLITAN DISTRICT 153°30'E U 2 B 8 e R A B v La 8 I k S A e 0 >>34 S >>97 BIRKDALE Dr ! 1 k L Mining INDOOROOPILLY o Peel Is. 0 O n R e ! ster d Dunwich t BEENLEIGH che o k an n 1 R B M Co v iv U >>5 # 0 c a er B C s m k S U H Pine U 2 r il M R p ls A 9 d o A LEGEND L R 8 1 a K 2 O C R A d o U96 n c oa y d I G w d u BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL T n N S 2 27°30'S e h BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL A P P ) n 27°30'S i a k W p N v l R o a t B G R n a t a R t H k y A d O 5<< y 1 h e a d o i E MOUNT CROSBY r C n o C l KENMORE d g y S i A a 1 ! 97<< a n i C r n o L Cleveland Pt. r U r P n x U re B e h N 201 d o Raby Bay STATE-CONTROLLED ROAD 12A 9 a P I l YERONGA 201 w l h s v e 9 D y ea F E g l C p i ie san D d a C l CHANDLER 8 e t t y w 3 k I R CRIMSTON 2 w B w a o L C s n R E n a 905 1 S A ! 12 u o 2 T Fin r 1 ir e o H A b uc e S d O S ( ane C V h y d a F d k S N FUTURE STATE-CONTROLLED ROAD 4 11 c a PINE MOUNTAIN CR c T HOLLAND R 2 T d d o COOLANA d R d U R i R m n A L a i e o d 23 i a w l l CAPALABA R Mon k L l s m R L s M ao o a PAR K u S m uth Mt Crosby E PULLENVALE A p hA >>8 E n L R I a s B v a S R d I Sil ar R ALEXANDRA CLEVELAND OTHER ROAD n R LOGAN CITY e Hu E ! kw d - g R R M t T h o d G r es IVE o Y Mt. -

Woinarski J. C. Z., Legge S. M., Woolley L. A., Palmer R., Dickman C

Woinarski J. C. Z., Legge S. M., Woolley L. A., Palmer R., Dickman C. R., Augusteyn J., Doherty T. S., Edwards G., Geyle H., McGregor H., Riley J., Turpin J., Murphy B.P. (2020) Predation by introduced cats Felis catus on Australian frogs: compilation of species records and estimation of numbers killed. Wildlife Research, Vol. 47, Iss. 8, Pp 580-588. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1071/WR19182 1 2 3 Predation by introduced cats Felis catus on Australian frogs: compilation of species’ 4 records and estimation of numbers killed. 5 6 7 J.C.Z. Woinarskia*, S.M. Leggeb, L.A. Woolleya,k, R. Palmerc, C.R. Dickmand, J. Augusteyne, T.S. Dohertyf, 8 G. Edwardsg, H. Geylea, H. McGregorh, J. Rileyi, J. Turpinj, and B.P. Murphya 9 10 a NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, 11 Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 12 b NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Research, 13 University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; AND Fenner School of the Environment and 14 Society, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2602, Australia 15 c Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Bentley, WA 6983, 16 Australia 17 d NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Desert Ecology Research Group, School of Life and 18 Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 19 e Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Red Hill, QLD 4701, Australia 20 f Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences (Burwood campus), Deakin 21 University, Geelong, VIC 3216, Australia 22 g Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, PO Box 1120, Alice Springs, NT 0871, 23 Australia 24 h NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, School of Biological Sciences, University of Tasmania, 25 Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia i School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Ave, Bristol BS8 1TQ, United Kingdom. -

Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration Framework

Classification and comparison of natural and altered flow regimes to support an Australian trial of the Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration framework Author Mackay, Stephen J, Arthington, Angela H, James, Cassandra S Published 2014 Journal Title Ecohydrology Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.1473 Copyright Statement © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: [Title], Ecohydrology, Vol. 7, 2014, pp. 1485-1507, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eco.1473. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/67348 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Classification and comparison of natural and altered flow regimes to support an Australian trial of the Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration (ELOHA) framework Stephen J. Mackay1,2, Angela H. Arthington1 and Cassandra S. James1 1 Australian Rivers Institute, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Griffith University, Kessels Road, Nathan, 4111, Queensland, Australia. 2 To whom correspondence should be sent. Current address: Water Services, Department of Natural Resources and Mines, PO Box 5318 Townsville, Queensland, 4810. Telephone: +61 7 4799 7001 Fax +61 7 4799 7971 E-mail: [email protected] KEYWORDS Flow regulation; Model-based classification; Cluster-wise stability; Cluster validity; Dams; Environmental flow 1 ABSTRACT The Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration (ELOHA) is a new framework designed to develop environmental flow prescriptions for many streams and rivers in a user-defined geographic region or jurisdiction. This study presents hydrologic classifications and comparisons of natural and altered flows in southeast Queensland, Australia, to support the ecological steps of a field trial of the ELOHA framework.