AP U.S. HISTORY Teaching Periodization in Period 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Geology Timeline

Red Rock Canyon NCA Environmental Education Program Geology Timeline Grades: 3-12 Objective: Demonstrate the relative distance of events in Estimated Time: 15-30 minutes time Standards Met: Procedure: 3-5 grade: Lead in to topic by discussing the age of the o Science E.5.C Students earth and how long students think various things understand that features on the of the surrounding area are. Earth's surface are constantly changed by a combination of Ask a chaperone to hold one end of the yarn to slow and rapid processes. mark the beginning of the earth. Explain that the earth is 4.6 billion years old, and that you’ll be 6-8 grade: doing an activity to get a better understanding of o Science E.8.C Students the age of everything around you. understand that landforms result from a combination of Have the students walk with you to when rocks constructive and destructive first appear on earth, 12 feet from the chaperone, processes. and mark it with tape or yarn. Explain that to 9-12 grade: scale this represents 600 million years and how o Science E.12.C Students geology is measured on a much larger scale that understand evidence for we are used to looking at things. processes that take place on a geological time scale. Note: Depending on your class, it may be helpful to have the measurements pre-marked on the Materials Needed: yarn before doing activity with students. Ball of yarn or twine Method for measuring Continue on as a group to the third point, when Brightly colored tape or contrasting life begins on earth, 16 feet from the chaperone. -

Modernism and the Issue of Periodization

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 7 (2005) Issue 1 Article 3 Modernism and the Issue of Periodization Leonard Orr Washington State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Orr, Leonard. "Modernism and the Issue of Periodization." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 7.1 (2005): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1254> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 6557 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

Geologic History of the Earth 1 the Precambrian

Geologic History of the Earth 1 algae = very simple plants that Geologists are scientists who study the structure grow in or near the water of rocks and the history of the Earth. By looking at first = in the beginning at and examining layers of rocks and the fossils basic = main, important they contain they are able to tell us what the beginning = start Earth looked like at a certain time in history and billion = a thousand million what kind of plants and animals lived at that breathe = to take air into your lungs and push it out again time. carbon dioxide = gas that is produced when you breathe Scientists think that the Earth was probably formed at the same time as the rest out of our solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. The solar system may have be- certain = special gun as a cloud of dust, from which the sun and the planets evolved. Small par- complex = something that has ticles crashed into each other to create bigger objects, which then turned into many different parts smaller or larger planets. Our Earth is made up of three basic layers. The cen- consist of = to be made up of tre has a core made of iron and nickel. Around it is a thick layer of rock called contain = have in them the mantle and around that is a thin layer of rock called the crust. core = the hard centre of an object Over 4 billion years ago the Earth was totally different from the planet we live create = make on today. -

Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth Is Young" by Jeff Miller

1 Critical analysis of article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth is Young" by Jeff Miller Lorence G. Collins [email protected] Ken Woglemuth [email protected] January 7, 2019 Introduction The article by Dr. Jeff Miller can be accessed at the following link: http://apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=9&article=5641 and is an article published by Apologetic Press, v. 39, n.1, 2018. The problems start with the Article In Brief in the boxed paragraph, and with the very first sentence. The Bible does not give an age of the Earth of 6,000 to 10,000 years, or even imply − this is added to Scripture by Dr. Miller and other young-Earth creationists. R. C. Sproul was one of evangelicalism's outstanding theologians, and he stated point blank at the Legionier Conference panel discussion that he does not know how old the Earth is, and the Bible does not inform us. When there has been some apparent conflict, either the theologians or the scientists are wrong, because God is the Author of the Bible and His handiwork is in general revelation. In the days of Copernicus and Galileo, the theologians were wrong. Today we do not know of anyone who believes that the Earth is the center of the universe. 2 The last sentence of this "Article In Brief" is boldly false. There is almost no credible evidence from paleontology, geology, astrophysics, or geophysics that refutes deep time. Dr. Miller states: "The age of the Earth, according to naturalists and old- Earth advocates, is 4.5 billion years. -

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

Geologic Timeline

SCIENCE IN THE PARK: GEOLOGY GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE ANALOGY PURPOSE: To show students the order of events and time periods in geologic time and the order of events and ages of the physiographic provinces in Virginia. BACKGROUND: Exact dates for events change as scientists explore geologic time. Dates vary from resource to resource and may not be the same as the dates that appear in your text book. Analogies for geologic time: a 24 hour clock or a yearly calendar. Have students or groups of students come up with their own original analogy. Before you assign this activity, you may want to try it, depending on the age of the student, level of the class, or time constraints, you may want to leave out the events that have a date of less than 1 million years. ! Review conversions in the metric system before you begin this activity ! References L.S. Fichter, 1991 (1997) http://csmres.jmu.edu/geollab/vageol/vahist/images/Vahistry.PDF http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/geotime/age.html Wicander, Reed. Historical Geology. Fourth Edition. Toronto, Ontario: Brooks/Cole, 2004. Print. VIRGINIA STANDARDS OF LEARNING ES.10 The student will investigate and understand that many aspects of the history and evolution of the Earth can be inferred by studying rocks and fossils. Key concepts include: relative and absolute dating; rocks and fossils from many different geologic periods and epochs are found in Virginia. Developed by C.P. Anderson Page 1 SCIENCE IN THE PARK: GEOLOGY Building a Geologic Time Scale Time: Materials Meter stick, 5 cm adding machine tape, pencil, colored pencils Procedure 1. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 a Sermon Preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 A Sermon preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells Who are you? This is a question we only get to ask one another in the movies. The convention is for the question to be addressed by a woman to a handsome man just as she’s beginning to realize he isn’t the uncomplicated body-and-soulmate he first seemed to be. Here’s one typical scenario: the war is starting to go badly; the chief of the special unit takes a key officer aside, and sends him on a dangerous mission to infiltrate the enemy forces. This being Hollywood, the officer falls in love with a beautiful woman while in enemy territory. In a moment of passion and mystery, it dawns on her that he’s not like the local men. So her bewitched but mistrusting eyes stare into his, and she says, “Who are you?” Then there’s the science fiction version. In this case the man develops an annoying habit of suddenly, without warning, traveling in time, or turning into a caped superhero. Meanwhile the woman, though drawn to his awesome good looks and sympathetic to his commendable desire to save the universe, yet finds herself taking his unexpected and unusual absences rather personally. So on one of the few occasions she gets to look into his eyes when they’re not undergoing some kind of chemical transformation, she says, with the now-familiar, bewitched-but-mistrusting expression, “Who are you?” “Who are you?” We never ask one another this question for fear of sounding melodramatic, like we’re in a movie. -

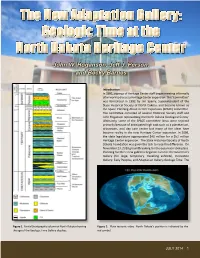

The New Adaption Gallery

Introduction In 1991, a group of Heritage Center staff began meeting informally after work to discuss a Heritage Center expansion. This “committee” was formalized in 1992 by Jim Sperry, Superintendent of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, and became known as the Space Planning About Center Expansion (SPACE) committee. The committee consisted of several Historical Society staff and John Hoganson representing the North Dakota Geological Survey. Ultimately, some of the SPACE committee ideas were rejected primarily because of anticipated high cost such as a planetarium, arboretum, and day care center but many of the ideas have become reality in the new Heritage Center expansion. In 2009, the state legislature appropriated $40 million for a $52 million Heritage Center expansion. The State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation was given the task to raise the difference. On November 23, 2010 groundbreaking for the expansion took place. Planning for three new galleries began in earnest: the Governor’s Gallery (for large, temporary, travelling exhibits), Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples, and Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. The Figure 1. Partial Stratigraphic column of North Dakota showing Figure 2. Plate tectonic video. North Dakota's position is indicated by the the age of the Geologic Time Gallery displays. red symbol. JULY 2014 1 Orientation Featured in the Orientation area is an interactive touch table that provides a timeline of geological and evolutionary events in North Dakota from 600 million years ago to the present. Visitors activate the timeline by scrolling to learn how the geology, environment, climate, and life have changed in North Dakota through time.