Emerging Disease Issues and Fungal Pathogens Associated with HIV Infection Neil M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congo DRC, Kamwiziku. Mycoses 2021

Received: 8 April 2021 | Revised: 1 June 2021 | Accepted: 10 June 2021 DOI: 10.1111/myc.13339 REVIEW ARTICLE Serious fungal diseases in Democratic Republic of Congo – Incidence and prevalence estimates Guyguy K. Kamwiziku1 | Jean- Claude C. Makangara1 | Emma Orefuwa2 | David W. Denning2,3 1Department of Microbiology, Kinshasa University Hospital, University of Abstract Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic A literature review was conducted to assess the burden of serious fungal infections of Congo 2Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (population 95,326,000). English and Geneva, Switzerland French publications were listed and analysed using PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar 3 Manchester Fungal Infection Group, The and the African Journals database. Publication dates spanning 1943– 2020 were in- University of Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, cluded in the scope of the review. From the analysis of published articles, we estimate Manchester, UK a total of about 5,177,000 people (5.4%) suffer from serious fungal infections in the Correspondence DRC annually. The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneu- Guyguy K. Kamwiziku, Department monia in adults and invasive aspergillosis in AIDS patients was estimated at 6168, of Microbiology, Kinshasa University Hospital, University of Kinshasa, Congo. 2800 and 380 cases per year. Oral and oesophageal candidiasis represent 50,470 Email: [email protected] and 28,800 HIV- infected patients respectively. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis post- tuberculosis incidence and prevalence was estimated to be 54,700. Fungal asthma (allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and severe asthma with fungal sensitiza- tion) probably has a prevalence of 88,800 and 117,200. -

Estimated Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in Ghana

Journal of Fungi Article Estimated Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in Ghana Bright K. Ocansey 1, George A. Pesewu 2,*, Francis S. Codjoe 2, Samuel Osei-Djarbeng 3, Patrick K. Feglo 4 and David W. Denning 5 1 Laboratory Unit, New Hope Specialist Hospital, Aflao 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box KB-143, Korle-Bu, Accra 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Kumasi Technical University, P.O. Box 854, Kumasi 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 4 Department of Clinical Microbiology, School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 5 National Aspergillosis Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital and the University of Manchester, Manchester M23 9LT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +233-277-301-300; Fax: +233-240-190-737 Received: 5 March 2019; Accepted: 14 April 2019; Published: 11 May 2019 Abstract: Fungal infections are increasingly becoming common and yet often neglected in developing countries. Information on the burden of these infections is important for improved patient outcomes. The burden of serious fungal infections in Ghana is unknown. We aimed to estimate this burden. Using local, regional, or global data and estimates of population and at-risk groups, deterministic modelling was employed to estimate national incidence or prevalence. Our study revealed that about 4% of Ghanaians suffer from serious fungal infections yearly, with over 35,000 affected by life-threatening invasive fungal infections. -

A Case of Disseminated Histoplasmosis Detected in Peripheral Blood Smear Staining Revealing AIDS at Terminal Phase in a Female Patient from Cameroon

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Medicine Volume 2012, Article ID 215207, 3 pages doi:10.1155/2012/215207 Case Report A Case of Disseminated Histoplasmosis Detected in Peripheral Blood Smear Staining Revealing AIDS at Terminal Phase in a Female Patient from Cameroon Christine Mandengue Ebenye Cliniques Universitaires des Montagnes, Bangangt´e, Cameroon Correspondence should be addressed to Christine Mandengue Ebenye, [email protected] Received 28 August 2012; Revised 2 November 2012; Accepted 5 November 2012 Academic Editor: Ingo W. Husstedt Copyright © 2012 Christine Mandengue Ebenye. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Histoplasmosis is endemic in the American continent and also in Sub-Saharan Africa, coexisting with the African histoplasmosis. Immunosuppressed patients, especially those with advanced HIV infection develop a severe disseminated histoplasmosis with fatal prognosis. The definitive diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis is based on the detection of Histoplasma capsulatum from patient’ tissues samples or body fluids. Among the diagnostic tests peripheral blood smear staining is not commonly used. Nonetheless a few publications reveal that Histoplasma capsulatum has been discovered by chance using this method in HIV infected patients with chronic fever and hence revealed AIDS at the terminal phase. We report a new case detected in a Cameroonian woman without any previous history of HIV infection. Peripheral blood smear staining should be commonly used for the diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis in the Sub-Saharan Africa, where facilities for mycology laboratories are unavailable. 1. Introduction 1987 [2]. -

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

Therapeutic Class Overview Onychomycosis Agents

Therapeutic Class Overview Onychomycosis Agents Therapeutic Class • Overview/Summary: This review will focus on the antifungal agents Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of onychomycosis.1-9 Onychomycosis is a progressive infection of the nail bed which may extend into the matrix or plate, leading to destruction, deformity, thickening and discoloration. Of note, these agents are only indicated when specific types of fungus have caused the infection, and are listed in Table 1. Additionally, ciclopirox is only FDA-approved for mild to moderate onychomycosis without lunula involvement.1 The mechanisms by which these agents exhibit their antifungal effects are varied. For ciclopirox (Penlac®) the exact mechanism is unknown. It is believed to block fungal transmembrane transport, causing intracellular depletion of essential substrates and/or ions and to interfere with ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).1 The azole antifungals, efinaconazole (Jublia®) and itraconazole tablets (Onmel®) and capsules (Sporanox®) works via inhibition of fungal lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase, an enzyme necessary for the biosynthesis of ergosterol. By decreasing ergosterol concentrations, the fungal cell membrane permeability is increased, which results in leakage of cellular contents.2,5,6 Griseofulvin microsize (Grifulvin V®) and ultramicrosize (GRIS-PEG®) disrupts the mitotic spindle, arresting metaphase of cell division. Griseofulvin may also produce defective DNA that is unable to replicate. The ultramicrosize tablets are absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract at approximately one and one-half times that of microsize griseofulvin, which allows for a lower dose of griseofulvin to be administered.3,4 Tavaborole (Kerydin®), is an oxaborole antifungal that interferes with protein biosynthesis by inhibiting leucyl-transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA) synthase (LeuRS), which prevents translation of tRNA by LeuRS.7 The final agent used for the treatment of onychomycosis, terbinafine hydrochloride (Lamisil®), is an allylamine antifungal. -

Pulmonary Aspergillosis: What CT Can Offer Before Radiology Section It Is Too Late!

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17141.7684 Review Article Pulmonary Aspergillosis: What CT can Offer Before Radiology Section it is too Late! AKHILA PRASAD1, KSHITIJ AGARWAL2, DESH DEEPAK3, SWAPNDEEP SINGH ATWAL4 ABSTRACT Aspergillus is a large genus of saprophytic fungi which are present everywhere in the environment. However, in persons with underlying weakened immune response this innocent bystander can cause fatal illness if timely diagnosis and management is not done. Chest infection is the most common infection caused by Aspergillus in human beings. Radiological investigations particularly Computed Tomography (CT) provides the easiest, rapid and decision making information where tissue diagnosis and culture may be difficult and time-consuming. This article explores the crucial role of CT and offers a bird’s eye view of all the radiological patterns encountered in pulmonary aspergillosis viewed in the context of the immune derangement associated with it. Keywords: Air-crescent, Fungal ball, Halo sign, Invasive aspergillosis INTRODUCTION diagnostic pitfalls one encounters and also addresses the crucial The genus Aspergillus comprises of hundreds of fungal species issue as to when to order for the CT. ubiquitously present in nature; predominantly in the soil and The spectrum of disease that results from the Aspergilla becoming decaying vegetation. Nearly, 60 species of Aspergillus are a resident in the lung is known as ‘Pulmonary Aspergillosis’. An medically significant, owing to their ability to cause infections inert colonization of pulmonary cavities like in cases of tuberculosis in human beings affecting multiple organ systems, chiefly the and Sarcoidosis, where cavity formation is quite common, makes lungs, paranasal sinuses, central nervous system, ears and skin. -

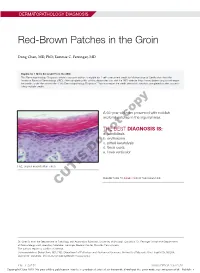

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Diagnostic Methods for Detection and Characterisation of Dimorphic Fungi Causing Invasive Disease in Africa: Development and Evaluation

Diagnostic methods for detection and characterisation of dimorphic fungi causing invasive disease in Africa: Development and evaluation TSIDISO GUGU MAPHANGA Diagnostic methods for detection and characterisation of dimorphic fungi causing invasive disease in Africa: Development and evaluation by TSIDISO GUGU MAPHANGA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR PhD (Medical Microbiology) in Department of Medical Microbiology Faculty of Health Sciences University of the Free State Bloemfontein, South Africa Promoter: A/Prof NP Govender March 2020 DECLARATION I, Tsidiso Gugu Maphanga, declare that the research thesis hereby submitted to the University of the Free State for the Doctoral Degree in Medical Microbiology and the work contained therein is my own original work and has not previously, in its entirety or in part, been submitted to any institution of higher education for degree purposes. I further declare that all sources cited are acknowledged by means of a list of references. Signed this day of 2020 Research is to see what everybody else has seen and to think what nobody else has thought Albert Szent-Györgi (US Biochemist) DEDICATION To my late brother, my mechanical engineer (Thabiso Benson Masilela): I will never forget all the plans we had, the motivations, love and laughter we shared. Life is never the same without you; I miss you daily. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, St Engenas and my God: Thank you for giving me strength, knowledge, wisdom and the ability to undertake this project. Your faithfulness reaches to the skies. A/Professor Nelesh P. Govender (supervisor): I would like to express my sincere gratitude for your patience, guidance, continuous support and useful comments received throughout this project. -

Bats (Myotis Lucifugus)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Wildlife Damage for January 1994 Bats (Myotis lucifugus) Arthur M. Greenhall Research Associate, Department of Mammalogy, American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York 10024 Stephen C. Frantz Vertebrate Vector Specialist, Wadsworth Center for Laboratories and Research, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York 12201-0509 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmhandbook Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Greenhall, Arthur M. and Frantz, Stephen C., "Bats (Myotis lucifugus)" (1994). The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. 46. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmhandbook/46 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Arthur M. Greenhall Research Associate Department of Mammalogy BATS American Museum of Natural History New York, New York 10024 Stephen C. Frantz Vertebrate Vector Specialist Wadsworth Center for Laboratories and Research New York State Department of Health Albany, New York 12201-0509 Fig. 1. Little brown bat, Myotis lucifugus Damage Prevention and Air drafts/ventilation. Removal of Occasional Bat Intruders Control Methods Ultrasonic devices: not effective. When no bite or contact has occurred, Sticky deterrents: limited efficacy. Exclusion help the bat escape (otherwise Toxicants submit it for rabies testing). Polypropylene netting checkvalves simplify getting bats out. None are registered. -

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA BRAND NAME (Generic) SPORANOX ORAL CAPSULES (Itraconazole)

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA BRAND NAME (generic) SPORANOX ORAL CAPSULES (itraconazole) Status: CVS Caremark Criteria Type: Initial Prior Authorization Policy FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Sporanox (itraconazole) Capsules are indicated for the treatment of the following fungal infections in immunocompromised and non-immunocompromised patients: 1. Blastomycosis, pulmonary and extrapulmonary 2. Histoplasmosis, including chronic cavitary pulmonary disease and disseminated, non-meningeal histoplasmosis, and 3. Aspergillosis, pulmonary and extrapulmonary, in patients who are intolerant of or who are refractory to amphotericin B therapy. Specimens for fungal cultures and other relevant laboratory studies (wet mount, histopathology, serology) should be obtained before therapy to isolate and identify causative organisms. Therapy may be instituted before the results of the cultures and other laboratory studies are known; however, once these results become available, antiinfective therapy should be adjusted accordingly. Sporanox Capsules are also indicated for the treatment of the following fungal infections in non-immunocompromised patients: 1. Onychomycosis of the toenail, with or without fingernail involvement, due to dermatophytes (tinea unguium), and 2. Onychomycosis of the fingernail due to dermatophytes (tinea unguium). Prior to initiating treatment, appropriate nail specimens for laboratory testing (KOH preparation, fungal culture, or nail biopsy) should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Compendial Uses Coccidioidomycosis2,3 -

Monoclonal Antibodies As Tools to Combat Fungal Infections

Journal of Fungi Review Monoclonal Antibodies as Tools to Combat Fungal Infections Sebastian Ulrich and Frank Ebel * Institute for Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, D-80539 Munich, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 November 2019; Accepted: 31 January 2020; Published: 4 February 2020 Abstract: Antibodies represent an important element in the adaptive immune response and a major tool to eliminate microbial pathogens. For many bacterial and viral infections, efficient vaccines exist, but not for fungal pathogens. For a long time, antibodies have been assumed to be of minor importance for a successful clearance of fungal infections; however this perception has been challenged by a large number of studies over the last three decades. In this review, we focus on the potential therapeutic and prophylactic use of monoclonal antibodies. Since systemic mycoses normally occur in severely immunocompromised patients, a passive immunization using monoclonal antibodies is a promising approach to directly attack the fungal pathogen and/or to activate and strengthen the residual antifungal immune response in these patients. Keywords: monoclonal antibodies; invasive fungal infections; therapy; prophylaxis; opsonization 1. Introduction Fungal pathogens represent a major threat for immunocompromised individuals [1]. Mortality rates associated with deep mycoses are generally high, reflecting shortcomings in diagnostics as well as limited and often insufficient treatment options. Apart from the development of novel antifungal agents, it is a promising approach to activate antimicrobial mechanisms employed by the immune system to eliminate microbial intruders. Antibodies represent a major tool to mark and combat microbes. Moreover, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are highly specific reagents that opened new avenues for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. -

Tinea Capitis 2014 L.C

BJD GUIDELINES British Journal of Dermatology British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of tinea capitis 2014 L.C. Fuller,1 R.C. Barton,2 M.F. Mohd Mustapa,3 L.E. Proudfoot,4 S.P. Punjabi5 and E.M. Higgins6 1Department of Dermatology, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, U.K. 2Department of Microbiology, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, U.K. 3British Association of Dermatologists, Willan House, 4 Fitzroy Square, London W1T 5HQ, U.K. 4St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, St Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London SE1 7EH, U.K. 5Department of Dermatology, Hammersmith Hospital, 150 Du Cane Road, London W12 0HS, U.K. 6Department of Dermatology, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, U.K. 1.0 Purpose and scope Correspondence Claire Fuller. The overall objective of this guideline is to provide up-to- E-mail: [email protected] date, evidence-based recommendations for the management of tinea capitis. This document aims to update and expand Accepted for publication on the previous guidelines by (i) offering an appraisal of 8 June 2014 all relevant literature since January 1999, focusing on any key developments; (ii) addressing important, practical clini- Funding sources cal questions relating to the primary guideline objective, i.e. None. accurate diagnosis and identification of cases; suitable treat- ment to minimize duration of disease, discomfort and scar- Conflicts of interest ring; and limiting spread among other members of the L.C.F. has received sponsorship to attend conferences from Almirall, Janssen and LEO Pharma (nonspecific); has acted as a consultant for Alliance Pharma (nonspe- community; (iii) providing guideline recommendations and, cific); and has legal representation for L’Oreal U.K.