18 Phoebe-Washburn.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gestolten CONTENT

MORE FLEETING ARCHITECTURE AND HIDEOUTS EDITED BY ROBERT KLANTEN AND LUKAS FEIREISS gestolten CONTENT SPACECRAFT 2 PAGE 004 LIVING IN A BOX PAGE 006 LET'S PLAY HOUSE PAGE 054 WHEN NATURE CALLS PAGE 088 WALK THIS WAY PAGE 134 JUST LOSE IT PAGE 180 BLOW UP PAGE 232 --------------------------------......q INDEX \ NOX PAGE 258 PIET HEIN EEK PAGES 1B2, 183 ROB VOERMAN PAGES 206, 207 Lars Spuybroek Netherlands I www.pietheineek.nl Netherlands I www.robvoerman.nl Netherlands I www.noxarch.com [KROLLER-MOLLER TICKET HOUSE I GAROENHOUSE TEAROOMJ [ANNEX # 4J Credits: Collection ABN-AMRO Bank [SON-O-HOUSEJ Credits: In collaboration with Chris Seung-woo Yoo, [TARNUNG # 2J Photos (interior): Berthold Stadler I Credits: Courtesy Josef Glas, Ludovica Tramontin, Kris Mun, Josef Glas, Geri Stavreva, PJOTR MULLER PAGE 19 Upstream Gallery and BodhiBerlin. exhibition made possible by the and Nicola Lammers Netherlands I pjotrmuller.org Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Architecture and Design and [HOUSE FOR OR. JUNGJ Photos: Rik Klein Gotink I Credits: www.phoebus.nl the Dutch Embassy. 02 TREEEHOUSE PAGE 124 Dustin Feider PRIMITIVO SUAREZ-WOLFE, GINGER WOLFE-SUAREZ 6 ROCIO ROMERO PAGE 30 USA I www.o2Treehouse.com AND MOIRA ROTH PAGE 27 [02 TREEHOUSE SEQUOIAJ Photos: Oustin Feider USA [SHELTER FOR POETRYJ Photos: Courtesy Yerba Buena Center for OBSERVATORIUM PAGES 52, 65, 94 the Arts Geert van de Camp, Andre Dekker, Ruud Reutelingsperger Netherlands I www.observatorium.org PROJECT OR PAGE 257 RODERICK ROMERO PAGES 121, 128 [PAVILION FOR ZECHE ZOLLVEREINJ -

Annual Report Food Is Hope

2013 ANNUAL REPORT FOOD IS HOPE. FOOD IS LOVE. FOOD IS MEDICINE. DEAR FRIENDS, uring our fiscal year 2013, the volunteers and staff We also finalized our plans this year to complete the transition from at God’s Love achieved astounding results for our a hot/frozen model to a chilled/frozen model. This change makes Dcommunity, delivering 1.2 million meals to 5,000 it easier for our clients to decide what they want to eat and when people – often in the face of extraordinary challenges. they want to eat it…a measure of control they told us they value. In October, Hurricane Sandy struck New York City, and our In Brooklyn, we found a location for our operations during the SoHo building lost power. Immediately following the storm, staff next phase of our Expansion Campaign. By the time you read this, and volunteers responded quickly, distributing more than 8,000 our move to Brooklyn will be complete, with no service disruptions meals to clients and other evacuees. Many of our clients were to our vulnerable clients who count on our meals every day. We without power. We assembled more than 2,300 nonperishable would also like to offer a special note of recognition to Michael meal kits, and delivered these throughout the five boroughs. Kors for his remarkable $5 million gift to our Expansion Campaign, and for joining our board. Throughout the year we continued to implement innovations to our programs. Our Nutrition Department published a new booklet, Of course, our work would not be possible without your “Nutrition Tips for Caregivers,” providing helpful strategies to extraordinary support. -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

Press Release

Press Release Whitney Museum of American Art Contact: 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Whitney Museum of American Art New York, NY 10021 212-570-3633 www.whitney.org/press Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] ARTISTS SELECTED FOR 2008 WHITNEY BIENNIAL, OPENING MARCH 6 New York, March 4, 2008 – Eighty-one artists are participating in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, which opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street, on March 6, and runs through June 1, 2008. Installations and performances organized by the Whitney and Art Production Fund,will also be presented in association with Park Avenue Armory (67th Street) from March 6-23. Since its founding in 1932, the Biennial has evolved into the Whitney’s signature exhibition as well as the most important survey of the state of contemporary art in the United States today. The exhibition will occupy the entire Museum, with the exception of the fifth floor, which is devoted to the permanent collection. For the first time, the Biennial will expand beyond the Museum’s Breuer building into Park Avenue Armory’s monumental Drill Hall and historic period rooms, creating an opportunity to present works that could not be accommodated within the Whitney’s walls and remaining true to the fluid, interactive way in which these works were conceived. The 2008 Biennial is curated by Henriette Huldisch, Assistant Curator at the Whitney, and Shamim M. Momin, Associate Curator at the Whitney and Branch Director and Curator of the Whitney Museum at Altria, and overseen by Donna De Salvo, the Whitney’s Chief Curator and Associate Director for Programs. -

The Stocking Ancestry

T HE S TOCKING A NCE S T RY II The date usually accepted as th at on wh i c h surnames came into recog . o D 1 0 0 0 . y o o ni ze d use is A . The were m re generally names b rr wed from wh i c h or estates on their wearers resided , and they , therefore , indicate igi of r nal landed proprietors . In process of time , the use su names was to on o extended natural obj ects , and later , to the professi ns and trades , and even to personal traits and characteristics . On the accession of to William the Conqueror to the English crown , he caused be published , in 1 0 8 —8 6 i 3 , a survey of the demesnes in his new k ngdom , with their metes o r and b unds , description of lands , varieties of tenures , classes of pe sons , o o . es kinds of m ney , statistical accounts , and hist rical matters From th e t k o o of William ascer ained a nowledge of the p ssessi ns the crown , the num - y ber of land holders , the militar strength , and best sources of revenue . m B ok This publication was known as D o esday o . It was the first record two published at the cost of the nation ; in volumes , it forms until the of hi ri of present day the basis sto cal records those ancient times , and fixes ! the domiciles of all the then families of p osition and respectability . -

The German Pavilion Team Welcomes You at the 52Nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale Di Venezia 2007

Welcome! The German Pavilion team welcomes you at the 52nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia 2007. Our press kit comprises following information: • Press information • Information in brief • Isa Genzken´s work “Oil” for the German Pavilion • Conversation between Isa Genzken and Nicolaus Schafhausen • Biography of the artist Isa Genzken • Biography of the curator Nicolaus Schafhausen • Background information of the German Pavilion • Press information of the commissioner Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt) • Press information of the collaborator Institute of Foreign Cultural Relations (ifa) • Press information of the main sponsor Deutsche Bank • Press information of the sponsor AXA Art Kunstversicherung • Press information of the media partner DW-TV – Deutsche Welle • Press information of the catalogue partner DuMont Literatur und Kunst Verlag • “Vogue Special German Pavilion” of the media partner Vogue Germany Thank you for your interest in the German Pavilion. We wish you a pleasant and in- spiring stay at Venice! Press Information Isa Genzken Oil German Pavilion La Biennale di Venezia 2007 Isa Genzken is the artist of the German contribution to the 52nd International Art Exhi- bition of the Biennale in Venice. The curator is Nicolaus Schafhausen, director of the Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam. For more than thirty years, Genzken (born in 1948) has been producing a diverse oeuvre that is continually being refined with new twists. Her extensive body of work includes sculpture and installations as well as photographs, collages and films. Genzken is creating an exhibition for the German Pavilion in Venice that envelops the architecture of the building, which is steeped in history, and presents it in a mise-en- scène that also comments that history. -

Architectsnewspaper 2004 27

THE ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER 27 2004 NEW YORK ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 CORNERSTONE LAID, CONSTRUCTION BEGINS CO 03 REVIVING UJ Freedom Tower JOHNSON RELIC o 05 FOUR VISIONS FOR Breaks Ground THE HIGH LINE Skeptics held their breath and The phrase "enduring spirit of politicians considered their freedom" was engraved in all- futures as the 20-ton cornerstone caps, twice the size of the com• HOW THE FAR WEST for Larry Siiverstein's Freedom memorative words, in a physical Tower was lowered onto its tem• marker of the political game the SIDE WILL BE WON porary wooden platform, 10 feet World Trade Center reconstruc• 14 above its final resting place. The tion has become. Under Sunday's granite stone was inscribed with cover of night, when all the offi• PERRIAND'S PUCE the words "To honor and remem• cials and photographers were will become invisible as con• the progress of the building's ber those who lost their lives on long gone, the stone was low• struction continues. It will not hold design, the groundbreaking did EAVESDROP September IT" and as a tribute to ered from its plinth to its under• any structural weight. carry more than symbolic weight: CURBSIDE the enduring spirit of freedom." ground resting place, where it Despite lingering doubts as to Construction continued on page 2 CLASSIFIEDS New York teenagers will have increased ANNE PAPAGEORGE LEAVES DDC ARCHITECTURE-CENTRIC PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS SPRING UP ACROSS NYC opportunities to study architecture in the near future as the city completes its plan to create FOR LMDC five new public high schools devoted to the field over the next two years. -

It Takes a Long Time to Become a Good Composer and Schumann’S Youthful Masterpiece, Metropolis Ensemble Kreisleriana

Supporters as of December 3, 2010 Special thanks to Glenn Schoenfeld for his tireless leadership of Metropolis. $50,000+ Judy and Rick Gilmore Nancy Hubbard Elizabeth and Paul De Rosa Jennifer and Eduardo Loja Olga Jobe June K. Wu Who’s in My Fund? Richard Klein Vern Kousky $15,000+ $250+ Gerard Laffan Argosy Foundation for Allegra Cummings and Fred Redd Kristin Lee Contemporary Music Lillian and Jack Davidson Lily Lim and Mateo Paiva Anne Dunning Joselin Linder $10,000+ Leila Mureebe Candice Madey and Ayal Brenner Crosswicks Foundation Anke Nolting Donald Matheson New York State Council for the Marcy Recktenwald and Ken Eberl Suzanne McClelland Arts Christopher Reiger Zain Mikho Mali Sananikone Gaw and Akarin Andrea and Dennis Roberts David Messer Gaw Helene Salomon Sarah Murkett The Richard Salomon Family Jocelyn Stone Daniel Neer Foundation Rosie Walker and Joe Fig Alexis Neophytides Paul Young and Franklin Evans Vladimir Nicenko $5,000+ Renata Parras Aaron Copland Foundation $100+ Andrey Pavlov Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Clay Andres Glenn Schoenfeld Hall Stephanie Amarnick Gabrielle Rieckhof Mikhail Iliev Ksenija Belsley Rachel Salomon Jill and Steve Lampe Anna Berlin and Ray Lustig Daniel Schofield Allyson and Trip Samson Astrid Baumgardner Andrew Schorr Andrew Cyr, Artistic Director / Conductor Jerome and Jodi Basdevant Jonathan Schorr $2,500+ Robert Bielecki Noah Smith American Chai Trust Asaf Buchner Cara Starke New York City Department of Dominic Carbone Ned Steiner It takes a long time Cultural Affairs Coralie Carlson -

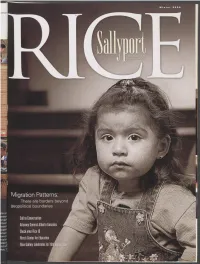

Migration Patterns: There Are Borders Beyond Geopolitical Boundaries

Winter 2006 7atIon Migration Patterns: There are borders beyond geopolitical boundaries ton ill On% omtal, Call to Conversation clear aneou Attorney General Alberto Gonzales erved Check your Rice Ri urrica enero Rice's Center for Education ollec' inc Iii Rice Gallery celebrates its 10th anniversary thes, INSIDE RICE SALLYPORT • THE MAGAZINE OF RICE UNIVERSITY • WINTER 2006 2 President's Message • 3 Through the Sallyport Departments 14 Students • 36 Arts • 44 On the Bookshelf 46 Who's Who • 52 Scoreboard 2Rice's largest-ever gift al Americans want to by an individual donor have their energy will go to strengthen exploration and wildlife the humanities. preservation, too. What implications for " the future can Houston expect in the aftetmath Are costly ofHurricane Katrina? breeding programs developed by zoos in the best interests of Who can help public endangered species? 10 schools? Strong mayors. The Texas Digital Library n Should retailers dare you initiative will improve to compare? Maybe not. Nr• access to high-quality Encouraging comparison information. shopping can backfire. In Important shifts in space Some run fast, some run far, policy may pose long-term 6 but never the twain shall meet threats to U.S. interests in in body mass index. space. 37Two Shepherd School Forget oil paint. Art at the pianists strike gold at the 38Rice Gallery celebrates Catania International unexpected media. Music Festival. ,n Coach Todd Graham Healthy, wealthy, and brings a fresh outlook 7male usually—but not to Owls football. always go together. Cover Photograph by Meg Reilley Features 16 Open to Interpretation Some see him as a loyal, sincere force behind the president. -

Best Companies Supporting the Arts in America the Boeing Company

Best Companies Supporting the Arts in America The Boeing Company The Boeing Company Chicago, Illinois Aerospace The Boeing Company believes that building strong communities requires creativity and imagination, skills that can be sharpened by participation in the arts. The company supports innovative projects that increase audiences and diversify the voices that create art. Each year it provides $12 million in grants to the arts, as well as in-kind donations and the expertise of its employees. Nominated by COCA – Center of Creative Arts St. Louis, Missouri Mark diSuvero sculpture in Millenium Park Chicago employees Boeing offers advice and counsel to arts organizations, loans executives to capital campaigns, recruits employees for service on boards and provides guidance in troubled times. Boeing’s Global Corporate Citizenship staff works with arts organizations to contribute to the organizations’ growth and development. For example, representatives of Boeing’s Global Corporate Citizenship staff conduct annual, in-depth interviews with the staff of Puget Sound arts and cultural organizations that the company funds. During these sessions, Boeing learns about each organization’s challenges and successes, and makes the organizations aware of the assistance the company might provide. Through its matching gift program, Boeing matches employees’ contributions to the arts dollar-for-dollar up to $6,000 per employee and $150,000 per organization each year. It encourages employee participation in the arts by offering free tickets to arts events at a number of its locations and, in its Chicago headquarters, employees receive a monthly e-mail with listings of arts and cultural events that employees can enjoy free or at a discounted price. -

Phoebe Washburn B

Phoebe Washburn b. 1973, Poughkeepsie, NY Lives and Works in New York, NY Education MFA, School of Visual Arts, New York, NY 2002 BFA, Newcomb College, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 1996 Solo Exhibitions 2013 Pressure Drop for Richard Stands (a history of one thing to another in lemon-aideness), Kunsthallen Brandts, Odense, Denmark 2012 Nudes, Housed Within Their Own Clothes and Aware of Their Individual Thirst, Descending a Staircase, National Academy Museum, New York, NY My Rubies and My Diamonds, Josée Bienvenu Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Nunderwater Nort Lab, Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, NY Temperatures in a Lab of Superior Specialness, Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY 2009 Compeshitstem: the new deal, Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, Germany 2008 Tickle the Shitstem, Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, NY 2007 Regulated Fool’s Milk Meadow, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany Vacational Trappings and Wildlife Worries, Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, PA 2006 2 BLT’s (Bought and Lovely Towns), Lipstick Building, 53rd and 3rd, New York, NY 2005 It Has No Secret Surprise, UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA It Makes For My Billionaire Status, Kantor/Feuer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2004 Nothing’s Cutie, LFL Gallery, New York, NY Bored Buys Options, The Weatherspoon Art Gallery, Greensboro, NC Greed. The Landscape Maker, Lerimonti Gallery, Milan, Italy 2003 Heavy has Debt, Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell University, Grinnell, IA True, False and Slightly Better, Rice University Gallery, Rice University, Houston, TX 2002 Between Sweet -

4930 VAJ Spring03 FC/IFC/BC/IBC

Visual Arts Journal School of Visual Arts Magazine | Spring 2003 School of VISUAL ARTS® PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGEPAID NEWYORK, NY Office of External Relations PERMIT NO. 3573 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 www.schoolofvisualarts.edu 4930 VAJ spring03 FC/IFC/BC/IBC 4/8/05 11:40 AM Page 1 4930 VAJ spring03 FC/IFC/BC/IBC 4/8/05 11:40 AM Page 2 SVA MERCHANDISE CLASSIC T-SHIRT Hanes Beefy-T, 100% cotton. Colors: Black, grey or denim blue. Sizes: S, M, L, XL and XXL. $15.95 WINDOW DECAL 4" in diameter, vinyl with removable adhesive on the front. $1.00 CAP Cotton twill, unconstructed low crown “Images are so omnipresent with a pre-curved visor, one size fits all. Black with red or gold embroidery. Khaki with black embroidery. $12.95 BUMPER STICKER 3" x 11" vinyl with removable adhesive on we assume the back. $1.50 WINDOW DECAL 1.5" x 18", vinyl with removable adhesive on the front. they will always be with us.” $2.00 SWEATSHIRT Lee Hooded Zipper, 50% cotton / 50% polyester. Sizes: S, M, L, XL. — Gene Stavis Hanes Hooded Pullover, 90% cotton / (see Point of View, page 5) 10% polyester. Sizes: S, M, L, XL and XXL. Both styles available in grey only. $35.00 CAPPUCCINO/SOUP MUG 16-oz. stoneware white mug. $9.95 MESSENGER BAG Black canvas bag with adjustable strap. $20.00 Merchandise available at Pearl Paint, 207 East 23 Street and SVA Office of External Relations, 209 East 23 Street, Room 209.