2 the Continental Shelf Before the United Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Shelf the Last Maritime Zone

Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone The Last Maritime Zone Published by UNEP/GRID-Arendal Copyright © 2009, UNEP/GRID-Arendal ISBN: 978-82-7701-059-5 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway Disclaimer Any views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/GRID-Arendal or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this book do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authority, or deline- ation of its frontiers and boundaries, nor do they imply the validity of submissions. All information in this publication is derived from official material that is posted on the website of the UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), which acts as the Secretariat to the Com- mission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): www.un.org/ Depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm. UNEP/GRID-Arendal is an official UNEP centre located in Southern Norway. GRID-Arendal’s mission is to provide environmental informa- tion, communications and capacity building services for information management and assessment. The centre’s core focus is to facili- tate the free access and exchange of information to support decision making to secure a sustainable future. www.grida.no. Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Authors and contributors Tina Schoolmeester and Elaine Baker (Editors) Joan Fabres Øystein Halvorsen Øivind Lønne Jean-Nicolas Poussart Riccardo Pravettoni (Cartography) Morten Sørensen Kristina Thygesen Cover illustration Alex Mathers Language editor Harry Forster (Interrelate Grenoble) Special thanks to Yannick Beaudoin Janet Fernandez Skaalvik Lars Kullerud Harald Sund (Geocap AS) Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Foreword During the past decade, many coastal States have been engaged in peacefully establish- ing the limits of their maritime jurisdiction. -

Directions for a Middle East Settlement—Some Underlying

DIRECTIONS FOR A MIDDLE EAST SETTLEMENT- SOME UNDERLYING LEGAL PROBLEMS SHABTAI ROSENNE* I INTRODUCTION A. Legal Framework of Arab-Israeli Relations The invitation to me to participate in this symposium suggested devoting attention primarily to the legal aspects and not to the facts. Yet there is great value in the civil law maxim: Narra mihi facta, narabo tibi jus. Law does not operate in a vacuum or in the abstract, but only in the closest contact with facts; and the merit of legal exposition depends directly upon its relationship with the facts. It is a fact that as part of its approach to the settlement of the current crisis, the Government of Israel is insistent that whatever solution is reached should be em- bodied in a secure legal regime of a contractual character directly binding on all the states concerned. International law in general, and the underlying international legal aspects of the crisis of the Middle East, are no exceptions to this legal approach which integrates law with the facts. But faced with the multitude of facts arrayed by one protagonist or another, sometimes facts going back to the remotest periods of prehistory, the first task of the lawyer is to separate the wheat from the chaff, to place first things first and last things last, and to discipline himself to the most rigorous standards of relevance that contemporary legal science imposes. The authority of the Interna- tional Court itself exists for this approach: the irony with which in I953 that august tribunal brushed off historical arguments, in that instance only going back to the early feudal period, will not be lost on the perceptive reader of international juris- prudence.' Another fundamental question which must be indicated at the outset relates to the very character of the legal framework within which the political issues are to be discussed and placed. -

Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice*

The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 12 (2013) 163–175 brill.com/lape Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice* Dame Rosalyn Higgins DBE QC Former President of the International Court of Justice It is by now well known in the world of international law that a new Judge at the International Court of Justice finds awaiting him or her on the office bookshelf not only the Pleadings, Judgments and Opinions of the Perma- nent Court of Justice and of the International Court of Justice, but the four volumes of Shabtai Rosenne’s The Law and Practice of the International Court, 1920–2005. Of course, there have over the years been many well-respected and knowledgeable writers on the Court. But the question arises: how could it be, that one who was never (for various reasons unrelated to his ability) a Judge of the International Court, produced thousands of pages, so full of insight and understanding, and precise in their formulation, that they have come to be regarded as somehow determinative of issues that arose in the life of the Court? These volumes were a marvel, yes, but how could they be so, especially as they were written by an author who had not ‘lived within the Court’? The answer is twofold: first, Shabtai Rosenne was a great, great man and scholar. Second, for nearly sixty years he had an ‘inside track’ at the Court. And he had it because he noted, he saw, he compared, and he asked, asked, and asked again – seeking information and explanations from seven Regis- trars. -

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Daphna Shraga * and Ralph Zacklin ** I. Introduction The key to an. understanding of the Statute of the International Tribunal for the prosecution of persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia (hereinafter International Tribunal or Tribunal) is the context within which the Security Council took its decision of principle to establish it1 By the end of February 1993 the conflict in the former Yugoslavia had been underway for more than 18 months, the principal focus of the conflict shifting from Slovenia to Croatia and then to Bosnia. United Nations involvement, through UNPROFOR, which at its inception had been conceived of as a protection force to shield pockets of Serbs in a newly independent Croatia (the United Nations Protected Areas) had gradually evolved into a multi-dimensional peace-keeping force whose main activities then centred on Bosnia. The character of the conflict had also evolved. While from the very beginning great brutality had marked the conduct of the parties, it was in Bosnia that the first signs of international crimes began to emerge: mass executions, mass sexual assaults and rapes, the existence of concentration camps and the implementation of a policy of so-called 'ethnic cleansing'. The Security Council repeatedly enjoined the parties to observe and comply with their obligations under international humanitarian law but the parties systematically ignored such injunctions. In October 1992 the Security Council, unable to control the wilful disregard by the parties for international norms, sought to create a dissuasive effect by asking the Secretary-General to establish a * Legal Officer, General Legal Division, Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations. -

Mapping the Canyon

Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon Mapping the Canyon FOCUS Part III: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon ❒ Library Books GRADE LEVEL AUDIO/VISUAL EQUIPMENT 9 - 12 Overhead Projector FOCUS QUESTION TEACHING TIME What are the differences between bathymetric Two 45-minute periods maps and topographic maps? SEATING ARRANGEMENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES Cooperative groups of two to four Students will be able to compare and contrast a topographic map to a bathymetric map. MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS 30 Students will investigate the various ways in which bathymetric maps are made. KEY WORDS Topography Students will learn how to interpret a bathymet- Bathymetry ric map. Map Multibeam sonar ADAPTATIONS FOR DEAF STUDENTS Canyon None required Contour lines SONAR MATERIALS Side-scan sonar Part I: GLORIA ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- Echo sounder parency ❒ 1 local topographic map BACKGROUND INFORMATION ❒ 1 USGS Fact Sheet on Sea Floor Mapping A map is a flat representation of all or part of Earth’s surface drawn to a specific scale Part II: (Tarbuck & Lutgens, 1999). Topographic maps show elevation of landforms above sea level, ❒ 1 local topographic map per group and bathymetric maps show depths of land- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map per group forms below sea level. The topographic eleva- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- tions and the bathymetric depths are shown parency ❒ with contour lines. A contour line is a line on a Contour Analysis Worksheet map representing a corresponding imaginary 59 Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon line on the ground that has the same elevation sonar is the multibeam sonar. -

The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: a Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad

Environment and Natural Resources Research; Vol. 4, No. 1; 2014 ISSN 1927-0488 E-ISSN 1927-0496 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: A Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad Junior Darsan1 & Christopher Alexis2 1 University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad 2 Institute of Marine Affairs, Chaguaramas, Trinidad Correspondence: Junior Darsan, Department of Geography, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 7, 2014 Accepted: February 7, 2014 Online Published: February 19, 2014 doi:10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 Abstract Coastal erosion threatens coastal land which is an invaluable limited resource to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Columbus Bay, located on the south-western peninsula of Trinidad, experiences high rates of coastal erosion which has resulted in the loss of millions of dollars to coconut estate owners. Owing to this, three makeshift sandbag groynes were installed in the northern region of Columbus Bay to arrest the coastal erosion problem. Beach profiles were conducted at eight stations from October 2009 to April 2011 to determine the change in beach widths and beach volumes along the bay. Beach width and volume changes were determined from the baseline in October 2009. Additionally, a generalized shoreline response model (GENESIS) was applied to Columbus Bay and simulated a 4 year model run. Results indicate that there was an increase in beach width and volume at five stations located within or adjacent to the groyne field. -

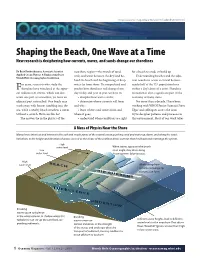

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

Sovereignty Over Land and Sea in the Arctic Area

Agenda Internacional Año XXIII N° 34, 2016, pp. 169-196 ISSN 1027-6750 Sovereignty over Land and Sea in the Arctic Area Tullio Scovazzi* Abstract The paper reviews the claims over land and waters in the Arctic area. While almost all the disputes over land have today been settled, several questions relating to law of the sea are still pending. They regard straight baselines, navigation in ice-covered areas, transit through inter- national straits, the outer limit of the continental shelf beyond 200 n.m. and delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between opposite or adjacent States. Keywords: straight baselines, navigation in ice-covered areas, transit passage in international straits, external limit of the continental shelf, exclusive economic zone La soberanía sobre tierra y mar en el área ártica Resumen El artículo examina los reclamos sobre el suelo y las aguas en el Ártico. Mientras que casi todas las disputas sobre el suelo han sido resueltas al día de hoy, aún quedan pendientes muchas cuestiones relativas al derecho del mar. Ellas están referidas a las líneas de base rectas, la navegación en las zonas cubiertas de hielo, el paso en tránsito en estrechos internacionales, el límite externo de la plataforma continental más allá de las 200 millas náu- ticas, y la delimitación de la zona económica exclusiva entre Estados adyacentes u opuestos. Palabras clave: Líneas de base rectas, navegación en zonas cubiertas de hielo, paso en tránsito en los estrechos internacionales, límite externo de la plataforma continental, zona económica exclusiva. * Professor of International Law, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy. -

1 PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1

PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1, D.J.R. Walstra1,2 , C.S Swinkels1 In October and November 2009 a pilot project has been executed at the Delfland Coast in the Netherlands, constructing three small sandy headlands called Sand Groynes. Sand Groynes are nourished from the shore in seaward direction and anticipated to redistribute in the alongshore due to the impact of waves and currents to create the sediment buffer in the upper shoreface. The results presented in this paper intend to contribute to the assessment of Sand Groynes as a commonly applied nourishment method to maintain sandy coastlines. The morphological evolution of the Sand Groynes has been monitored by regularly conducting bathymetry surveys, resulting in a series of available bathymetry surveys. It is observed that the Sand Groynes have been redistributed in the alongshore, mainly in northward direction driven by dominant southwesterly wave conditions. Furthermore, data analysis suggests that Sand Groynes have a trapping capacity for alongshore supplied sand originating from upstream located Sand Groynes. A Delft3D numerical model has been set up to verify whether the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes can be properly hindcasted. Although the model has been set up in 2DH mode, hindcast results show good agreement with the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes based on field data. Trends of alongshore redistribution of Sand Groynes are well reproduced. Still the model performance could be improved, for instance by implementation of 3D velocity patterns and by a more accurate schematization of sediment characteristics. Keywords: Sand Groyne, Delfland Coast, sand nourishment, sediment transport, Delft3D INTRODUCTION Objective The main objective of this paper is to asses an innovative sand nourishment method to maintain a sandy coastline, by constructing small sandy headlands in the upper shoreface called Sand Groynes (see Figure 1). -

Professor Shabtai Rosenne (1917-2010) Possessed of a Powerful Personality and a Towering Intellect, Shabtai Rosenne Bestrode Two Worlds

Professor Shabtai Rosenne (1917-2010) Possessed of a powerful personality and a towering intellect, Shabtai Rosenne bestrode two worlds. As an Israeli diplomat, he helped shape the institutions of gov- ernment from pre-state days and remained a person of consequence to his last days. As an international lawyer, his contributions were vast, infl uential and unmatched. He has been described as one of the foremost international lawyers of the second half of the twentieth century. He mixed encyclopaedic knowledge of the law with a profound understanding of practice. He was the preeminent well-rounded interna- tional lawyer. He died aged 92 on 21 September 2010. Rosenne’s inspiration, as his speech accepting the highly prestigious Hague Prize for International Law in 2004 underlined time and again, was the Biblical instruc- tion demanding that “justice, justice shalt thou pursue”. He, typically, devoted that speech to the place of international law in the daily life of the average human being. Proud of his Jewish heritage and extraordinarily knowledgeable about it, Rosenne became the supreme international law universalist. His quest for knowledge was insatiable and he formed, for example, a close friendship with Judge Nagendra Singh of the International Court of Justice, based not least upon a shared love of Hindu philosophy. His writings on that Court, including a four volume colossus, made him the foremost authority on its law and practice and it is well known that generations of judges consulted him quietly on diffi cult questions. He would undoubtedly have been elected a judge had it not been for the political constellation of those years. -

The Open Ocean

THE OPEN OCEAN Grade 5 Unit 6 THE OPEN OCEAN How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? What do we mean by the “open ocean”? How do we describe the open oceans of Hawai’i? The World’s Oceans The ocean is the world’s largest habitat. It covers about 70% of the Earth’s surface. Scientists divide the ocean into two main zones: Pelagic Zone: The open ocean that is not near the coast. pelagic zone Benthic Zone: The ocean bottom. benthic zone Ocean Zones pelagic zone Additional Pelagic Zones Photic zone Aphotic zone Pelagic Zones The Hawaiian Islands do not have a continental shelf Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore : anything over 500 meters from shore Inshore Ecosystems Offshore Ecosystems Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Answer: 70% of the Earth is covered by ocean water. Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Answer: Pelagic Zone-the open ocean not near the coast. Benthic Zone-ocean bottom. Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Answer: Photic zone- where sunlight penetrates Aphotic zone- where sunlight cannot penetrate Neritic zone- over the continental shelf Oceanic zone- beyond the continental shelf Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Answer: Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore: anything over 500 meters from shore . -

Coastal Ocean and Continental Shelves

Coastal Ocean and 16 Continental Shelves Lead Author Katja Fennel, Dalhousie University Contributing Authors Simone R. Alin, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory; Leticia Barbero, NOAA Atlantic Ocean- ographic and Meteorological Laboratory; Wiley Evans, Hakai Institute; Timothée Bourgeois, Dalhousie Uni- versity; Sarah R. Cooley, Ocean Conservancy; John Dunne, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory; Richard A. Feely, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory; Jose Martin Hernandez-Ayon, Auton- omous University of Baja California; Chuanmin Hu, University of South Florida; Xinping Hu, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi; Steven E. Lohrenz, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth; Frank Muller-Karger, University of South Florida; Raymond G. Najjar, The Pennsylvania State University; Lisa Robbins, University of South Florida; Joellen Russell, University of Arizona; Elizabeth H. Shadwick, College of William & Mary; Samantha Siedlecki, University of Connecticut; Nadja Steiner, Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Daniela Turk, Dalhousie University; Penny Vlahos, University of Connecticut; Zhaohui Aleck Wang, Woods Hole Oceano- graphic Institution Acknowledgments Raymond G. Najjar (Science Lead), The Pennsylvania State University; Marjorie Friederichs (Review Editor), Virginia Institute of Marine Science; Erica H. Ombres (Federal Liaison), NOAA Ocean Acidification Program; Laura Lorenzoni (Federal Liaison), NASA Earth Science Division Recommended Citation for Chapter Fennel, K., S. R. Alin, L. Barbero, W. Evans, T. Bourgeois, S. R. Cooley, J. Dunne, R. A. Feely, J. M. Hernandez-Ayon, C. Hu, X. Hu, S. E. Lohrenz, F. Muller-Karger, R. G. Najjar, L. Robbins, J. Russell, E. H. Shadwick, S. Siedlecki, N. Steiner, D. Turk, P. Vlahos, and Z. A. Wang, 2018: Chapter 16: Coastal ocean and continental shelves. In Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2): A Sustained Assessment Report [Cavallaro, N., G.