Mapping the Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Shelf the Last Maritime Zone

Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone The Last Maritime Zone Published by UNEP/GRID-Arendal Copyright © 2009, UNEP/GRID-Arendal ISBN: 978-82-7701-059-5 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway Disclaimer Any views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/GRID-Arendal or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this book do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authority, or deline- ation of its frontiers and boundaries, nor do they imply the validity of submissions. All information in this publication is derived from official material that is posted on the website of the UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), which acts as the Secretariat to the Com- mission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): www.un.org/ Depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm. UNEP/GRID-Arendal is an official UNEP centre located in Southern Norway. GRID-Arendal’s mission is to provide environmental informa- tion, communications and capacity building services for information management and assessment. The centre’s core focus is to facili- tate the free access and exchange of information to support decision making to secure a sustainable future. www.grida.no. Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Authors and contributors Tina Schoolmeester and Elaine Baker (Editors) Joan Fabres Øystein Halvorsen Øivind Lønne Jean-Nicolas Poussart Riccardo Pravettoni (Cartography) Morten Sørensen Kristina Thygesen Cover illustration Alex Mathers Language editor Harry Forster (Interrelate Grenoble) Special thanks to Yannick Beaudoin Janet Fernandez Skaalvik Lars Kullerud Harald Sund (Geocap AS) Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Foreword During the past decade, many coastal States have been engaged in peacefully establish- ing the limits of their maritime jurisdiction. -

Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California S

LITTORAL CELLS, SAND BUDGETS, AND BEACHES: UNDERSTANDING CALIFORNIA’ S SHORELINE KIKI PATSCH GARY GRIGGS OCTOBER 2006 INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF BOATING AND WATERWAYS CALIFORNIA COASTAL SEDIMENT MANAGEMENT WORKGROUP Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California’s Shoreline By Kiki Patch Gary Griggs Institute of Marine Sciences University of California, Santa Cruz California Department of Boating and Waterways California Coastal Sediment Management WorkGroup October 2006 Cover Image: Santa Barbara Harbor © 2002 Kenneth & Gabrielle Adelman, California Coastal Records Project www.californiacoastline.org Brochure Design & Layout Laura Beach www.LauraBeach.net Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California’s Shoreline Kiki Patsch Gary Griggs Institute of Marine Sciences University of California, Santa Cruz TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 7 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: An Overview of Littoral Cells and Littoral Drift 11 Chapter 3: Elements Involved in Developing Sand Budgets for Littoral Cells 17 Chapter 4: Sand Budgets for California’s Major Littoral Cells and Changes in Sand Supply 23 Chapter 5: Discussion of Beach Nourishment in California 27 Chapter 6: Conclusions 33 References Cited and Other Useful References 35 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he coastline of California can be divided into a set of dis- Beach nourishment or beach restoration is the placement of Ttinct, essentially self-contained littoral cells or beach com- sand on the shoreline with the intent of widening a beach that partments. These compartments are geographically limited and is naturally narrow or where the natural supply of sand has consist of a series of sand sources (such as rivers, streams and been signifi cantly reduced through human activities. -

Feasibility Study of an Artifical Sandy Beach at Batumi, Georgia

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF AN ARTIFICAL SANDY BEACH AT BATUMI, GEORGIA ARCADIS/TU DELFT : MSc Report FEASIBILITY STUDY OF AN ARTIFICAL SANDY BEACH AT BATUMI, GEORGIA Date May 2012 Graduate C. Pepping Educational Institution Delft University of Technology, Faculty Civil Engineering & Geosciences Section Hydraulic Engineering, Chair of Coastal Engineering MSc Thesis committee Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive Delft University of Technology Dr. ir. M. Zijlema Delft University of Technology Ir. J. van Overeem Delft University of Technology Ir. M.C. Onderwater ARCADIS Nederland BV Company ARCADIS Nederland BV, Division Water PREFACE Preface This Master thesis is the final part of the Master program Hydraulic Engineering of the chair Coastal Engineering at the faculty Civil Engineering & Geosciences of the Delft University of Technology. This research is done in cooperation with ARCADIS Nederland BV. The report represents the work done from July 2011 until May 2012. I would like to thank Jan van Overeem and Martijn Onderwater for the opportunity to perform this research at ARCADIS and the opportunity to graduate on such an interesting subject with many different aspects. I would also like to thank Robbin van Santen for all his help and assistance for the XBeach model. Furthermore I owe a special thanks to my graduation committee for the valuable input and feedback: Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive (Delft University of Technology) for his support and interest in my graduation work; Dr. ir. M. Zijlema (Delft University of Technology) for his support and reviewing the report; ir. J. van Overeem (Delft University of Technology ) for his supervisions, useful feedback and help, support and for reviewing the report; and ir. -

Recent Sediments of the Monterey Deep-Sea Fan

UC Berkeley Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory Reports Title Recent Sediments of the Monterey Deep-Sea Fan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5f440431 Author Wilde, Pat Publication Date 1965-05-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California RECENT SEDIMENTS OF THE MONTEREY DEEP-SEA FAN A thesis presented by Pat Wilde to The Department of Geological Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doc tor of Philosophy in the subject of Geology Harvard Univer sity Cambridge, Massachusetts May 1965 Copyright reserved by the author University of California Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory Submitted under Contract DA- 49- 055-CIV-ENG- 63-4 with the Coastal Engineering Research Center, U. S. Army Technical Report No. HEL-2-13 RECENT SEDIMENTS OF THE MONTEREY DEEP-SEA FAN by Pat Wilde Berkeley, California May, 1965 CONTENTS Page Abstract ................... 1 Introduction ...................... 5 Definition ..................... 5 Location ..................... 5 Regional Setting .............. 8 Subjects of Investigation ............... 9 Sources of Data .................. 10 Acknowledgements ................ 10 Geomorphology ..................11 Major Features ..............'11 FanSlope ................... 11 Under sea Positive Relief ............15 Submarine Canyon-Channel Systems . 16 Hydraulic Geometry ................ 19 Calculations ............... 19 Comparison with other Channel Systems ..30 Lithology ........................32 Sampling Techniques ............... -

Measuring Currents in Submarine Canyons: Technological and Scientifi C Progress in the Past 30 Years

Exploring the Deep Sea and Beyond themed issue Measuring currents in submarine canyons: Technological and scientifi c progress in the past 30 years J.P. Xu U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, MS-999, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION processes, and summarize and discuss several future research challenges constructed primar- The development and application of The publication of the American Association ily for submarine canyons in temperate climate, acoustic and optical technologies and of of Petroleum Geologists Studies in Geology 8: such as the California coast. accurate positioning systems in the past Currents in Submarine Canyons and Other Sea 30 years have opened new frontiers in the Valleys (Shepard et al., 1979) marked a signifi - 2. TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES submarine canyon research communities. cant milestone in submarine canyon research. IN CURRENT OBSERVATION IN This paper reviews several key advance- Although there had been studies on the topics of SUBMARINE CANYONS ments in both technology and science in the submarine canyon hydrodynamics and sediment fi eld of currents in submarine canyons since processes in various journals since the 1930s 2.1. Instrumentation the1979 publication of Currents in Subma- (Shepard et al., 1939; Emory and Hulsemann, rine Canyons and Other Sea Valleys by Fran- 1963; Ryan and Heezen 1965; Inman, 1970; Instrument development has come a long way cis Shepard and colleagues. Precise place- Drake and Gorsline, 1973; Shepard, 1975), this in the past 30 yr. The greatest leap in the tech- ments of high-resolution, high-frequency book was the fi rst of its kind to provide descrip- nology of fl ow measurements was the transition instruments have not only allowed research- tion and discussion on the various phenomena from mechanical to acoustic current meters. -

Dynamics of Beach Sand Made Easy

Dynamics of Beaches Made Easy Page 1 Dynamics Of Beaches Made Easy San Diego County Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation 1. Introduction Beaches are made up of more than just sand. In California beaches are generally formed by erosion of uplifted plates resulting in cliff backed beaches or in the delta areas of rivers or watersheds. Beach sand is an important element of beaches but not the only element. Wavecut platforms or tidal terraces are equally important in many areas of San Diego. The movement of beach sand is governed by many complex processes and variables. However, there are a few very basic elements that tend to control not only how much sand ends up on our beaches, but also how much sand exists near enough to the shore to be deposited on the beach under favorable conditions. The following is a brief description of the most important issues influencing the current condition of our local beaches with respect to sand. Dynamics of Beaches Made Easy Page 2 2. Geology The geology of San Diego County varies from sea cliffs to sandy beaches. Beaches are generally found at the mouths of lagoons or in the lagoon or river outfalls. Cliffs formed by tectonic activity and the erosion via marine forces deserve special mention. Much of San Diego’s coastline consists of a wavecut platform sometimes referred to as a tidal terrace. A wavecut platform is formed where a seacliff is eroded by marine action, meaning waves, resulting in the deposition of cliff material and formation of a bedrock area where erosion occurred. -

The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: a Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad

Environment and Natural Resources Research; Vol. 4, No. 1; 2014 ISSN 1927-0488 E-ISSN 1927-0496 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: A Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad Junior Darsan1 & Christopher Alexis2 1 University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad 2 Institute of Marine Affairs, Chaguaramas, Trinidad Correspondence: Junior Darsan, Department of Geography, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 7, 2014 Accepted: February 7, 2014 Online Published: February 19, 2014 doi:10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 Abstract Coastal erosion threatens coastal land which is an invaluable limited resource to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Columbus Bay, located on the south-western peninsula of Trinidad, experiences high rates of coastal erosion which has resulted in the loss of millions of dollars to coconut estate owners. Owing to this, three makeshift sandbag groynes were installed in the northern region of Columbus Bay to arrest the coastal erosion problem. Beach profiles were conducted at eight stations from October 2009 to April 2011 to determine the change in beach widths and beach volumes along the bay. Beach width and volume changes were determined from the baseline in October 2009. Additionally, a generalized shoreline response model (GENESIS) was applied to Columbus Bay and simulated a 4 year model run. Results indicate that there was an increase in beach width and volume at five stations located within or adjacent to the groyne field. -

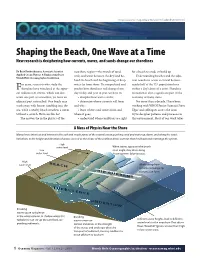

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

1 PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1

PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1, D.J.R. Walstra1,2 , C.S Swinkels1 In October and November 2009 a pilot project has been executed at the Delfland Coast in the Netherlands, constructing three small sandy headlands called Sand Groynes. Sand Groynes are nourished from the shore in seaward direction and anticipated to redistribute in the alongshore due to the impact of waves and currents to create the sediment buffer in the upper shoreface. The results presented in this paper intend to contribute to the assessment of Sand Groynes as a commonly applied nourishment method to maintain sandy coastlines. The morphological evolution of the Sand Groynes has been monitored by regularly conducting bathymetry surveys, resulting in a series of available bathymetry surveys. It is observed that the Sand Groynes have been redistributed in the alongshore, mainly in northward direction driven by dominant southwesterly wave conditions. Furthermore, data analysis suggests that Sand Groynes have a trapping capacity for alongshore supplied sand originating from upstream located Sand Groynes. A Delft3D numerical model has been set up to verify whether the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes can be properly hindcasted. Although the model has been set up in 2DH mode, hindcast results show good agreement with the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes based on field data. Trends of alongshore redistribution of Sand Groynes are well reproduced. Still the model performance could be improved, for instance by implementation of 3D velocity patterns and by a more accurate schematization of sediment characteristics. Keywords: Sand Groyne, Delfland Coast, sand nourishment, sediment transport, Delft3D INTRODUCTION Objective The main objective of this paper is to asses an innovative sand nourishment method to maintain a sandy coastline, by constructing small sandy headlands in the upper shoreface called Sand Groynes (see Figure 1). -

New York Department of State Offshore Atlantic Ocean Study

New York Department of State Offshore Atlantic Ocean Study July 2013 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK Acknowledgements The New York State Department of State (DOS) recognizes and appreciates the federal, state, and public partnerships that made this offshore study possible. Thanks to the many stakeholders that participated in the data workshops and provided their passion and expertise. Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County provided invaluable assistance working with commercial fishers and boat-for-hire captains, who generously shared their time and local knowledge. New York State agencies provided support through their participation in the Offshore Renewable Energy Work Group and the Offshore Habitat Work Group. Both work groups are chaired by DOS and include representatives from: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; New York State Energy Research and Development Authority; New York State Office of General Services; and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. The Offshore Renewable Energy Work Group also includes representatives from: New York State Department of Public Service/Public Service Commission; Empire State Development; and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The Offshore Habitat Work Group also includes issue-area experts from: the State University of New York at Stony Brook; The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Centers for Coastal and Ocean Science’s (NCCOS); and the Riverhead Foundation. Federal staff were responsive to DOS’s requests and needs and helpful in translating information they developed for the offshore planning area: NCCOS’s Biogeography Branch provided geostatistical analysis and ecological modeling that was invaluable to the Habitat Work Group’s efforts. -

The Open Ocean

THE OPEN OCEAN Grade 5 Unit 6 THE OPEN OCEAN How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? What do we mean by the “open ocean”? How do we describe the open oceans of Hawai’i? The World’s Oceans The ocean is the world’s largest habitat. It covers about 70% of the Earth’s surface. Scientists divide the ocean into two main zones: Pelagic Zone: The open ocean that is not near the coast. pelagic zone Benthic Zone: The ocean bottom. benthic zone Ocean Zones pelagic zone Additional Pelagic Zones Photic zone Aphotic zone Pelagic Zones The Hawaiian Islands do not have a continental shelf Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore : anything over 500 meters from shore Inshore Ecosystems Offshore Ecosystems Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Answer: 70% of the Earth is covered by ocean water. Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Answer: Pelagic Zone-the open ocean not near the coast. Benthic Zone-ocean bottom. Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Answer: Photic zone- where sunlight penetrates Aphotic zone- where sunlight cannot penetrate Neritic zone- over the continental shelf Oceanic zone- beyond the continental shelf Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Answer: Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore: anything over 500 meters from shore . -

Coastal Ocean and Continental Shelves

Coastal Ocean and 16 Continental Shelves Lead Author Katja Fennel, Dalhousie University Contributing Authors Simone R. Alin, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory; Leticia Barbero, NOAA Atlantic Ocean- ographic and Meteorological Laboratory; Wiley Evans, Hakai Institute; Timothée Bourgeois, Dalhousie Uni- versity; Sarah R. Cooley, Ocean Conservancy; John Dunne, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory; Richard A. Feely, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory; Jose Martin Hernandez-Ayon, Auton- omous University of Baja California; Chuanmin Hu, University of South Florida; Xinping Hu, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi; Steven E. Lohrenz, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth; Frank Muller-Karger, University of South Florida; Raymond G. Najjar, The Pennsylvania State University; Lisa Robbins, University of South Florida; Joellen Russell, University of Arizona; Elizabeth H. Shadwick, College of William & Mary; Samantha Siedlecki, University of Connecticut; Nadja Steiner, Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Daniela Turk, Dalhousie University; Penny Vlahos, University of Connecticut; Zhaohui Aleck Wang, Woods Hole Oceano- graphic Institution Acknowledgments Raymond G. Najjar (Science Lead), The Pennsylvania State University; Marjorie Friederichs (Review Editor), Virginia Institute of Marine Science; Erica H. Ombres (Federal Liaison), NOAA Ocean Acidification Program; Laura Lorenzoni (Federal Liaison), NASA Earth Science Division Recommended Citation for Chapter Fennel, K., S. R. Alin, L. Barbero, W. Evans, T. Bourgeois, S. R. Cooley, J. Dunne, R. A. Feely, J. M. Hernandez-Ayon, C. Hu, X. Hu, S. E. Lohrenz, F. Muller-Karger, R. G. Najjar, L. Robbins, J. Russell, E. H. Shadwick, S. Siedlecki, N. Steiner, D. Turk, P. Vlahos, and Z. A. Wang, 2018: Chapter 16: Coastal ocean and continental shelves. In Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2): A Sustained Assessment Report [Cavallaro, N., G.