Coastal Ocean and Continental Shelves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Shelf the Last Maritime Zone

Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone The Last Maritime Zone Published by UNEP/GRID-Arendal Copyright © 2009, UNEP/GRID-Arendal ISBN: 978-82-7701-059-5 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway Disclaimer Any views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/GRID-Arendal or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this book do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authority, or deline- ation of its frontiers and boundaries, nor do they imply the validity of submissions. All information in this publication is derived from official material that is posted on the website of the UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), which acts as the Secretariat to the Com- mission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): www.un.org/ Depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm. UNEP/GRID-Arendal is an official UNEP centre located in Southern Norway. GRID-Arendal’s mission is to provide environmental informa- tion, communications and capacity building services for information management and assessment. The centre’s core focus is to facili- tate the free access and exchange of information to support decision making to secure a sustainable future. www.grida.no. Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Authors and contributors Tina Schoolmeester and Elaine Baker (Editors) Joan Fabres Øystein Halvorsen Øivind Lønne Jean-Nicolas Poussart Riccardo Pravettoni (Cartography) Morten Sørensen Kristina Thygesen Cover illustration Alex Mathers Language editor Harry Forster (Interrelate Grenoble) Special thanks to Yannick Beaudoin Janet Fernandez Skaalvik Lars Kullerud Harald Sund (Geocap AS) Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Foreword During the past decade, many coastal States have been engaged in peacefully establish- ing the limits of their maritime jurisdiction. -

Mapping the Canyon

Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon Mapping the Canyon FOCUS Part III: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon ❒ Library Books GRADE LEVEL AUDIO/VISUAL EQUIPMENT 9 - 12 Overhead Projector FOCUS QUESTION TEACHING TIME What are the differences between bathymetric Two 45-minute periods maps and topographic maps? SEATING ARRANGEMENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES Cooperative groups of two to four Students will be able to compare and contrast a topographic map to a bathymetric map. MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS 30 Students will investigate the various ways in which bathymetric maps are made. KEY WORDS Topography Students will learn how to interpret a bathymet- Bathymetry ric map. Map Multibeam sonar ADAPTATIONS FOR DEAF STUDENTS Canyon None required Contour lines SONAR MATERIALS Side-scan sonar Part I: GLORIA ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- Echo sounder parency ❒ 1 local topographic map BACKGROUND INFORMATION ❒ 1 USGS Fact Sheet on Sea Floor Mapping A map is a flat representation of all or part of Earth’s surface drawn to a specific scale Part II: (Tarbuck & Lutgens, 1999). Topographic maps show elevation of landforms above sea level, ❒ 1 local topographic map per group and bathymetric maps show depths of land- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map per group forms below sea level. The topographic eleva- ❒ 1 Hudson Canyon Bathymetry map trans- tions and the bathymetric depths are shown parency ❒ with contour lines. A contour line is a line on a Contour Analysis Worksheet map representing a corresponding imaginary 59 Deep East 2001— Grades 9-12 Focus: Bathymetry of Hudson Canyon line on the ground that has the same elevation sonar is the multibeam sonar. -

The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: a Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad

Environment and Natural Resources Research; Vol. 4, No. 1; 2014 ISSN 1927-0488 E-ISSN 1927-0496 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Impact of Makeshift Sandbag Groynes on Coastal Geomorphology: A Case Study at Columbus Bay, Trinidad Junior Darsan1 & Christopher Alexis2 1 University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad 2 Institute of Marine Affairs, Chaguaramas, Trinidad Correspondence: Junior Darsan, Department of Geography, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 7, 2014 Accepted: February 7, 2014 Online Published: February 19, 2014 doi:10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v4n1p94 Abstract Coastal erosion threatens coastal land which is an invaluable limited resource to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Columbus Bay, located on the south-western peninsula of Trinidad, experiences high rates of coastal erosion which has resulted in the loss of millions of dollars to coconut estate owners. Owing to this, three makeshift sandbag groynes were installed in the northern region of Columbus Bay to arrest the coastal erosion problem. Beach profiles were conducted at eight stations from October 2009 to April 2011 to determine the change in beach widths and beach volumes along the bay. Beach width and volume changes were determined from the baseline in October 2009. Additionally, a generalized shoreline response model (GENESIS) was applied to Columbus Bay and simulated a 4 year model run. Results indicate that there was an increase in beach width and volume at five stations located within or adjacent to the groyne field. -

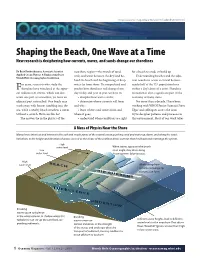

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

1 PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1

PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1, D.J.R. Walstra1,2 , C.S Swinkels1 In October and November 2009 a pilot project has been executed at the Delfland Coast in the Netherlands, constructing three small sandy headlands called Sand Groynes. Sand Groynes are nourished from the shore in seaward direction and anticipated to redistribute in the alongshore due to the impact of waves and currents to create the sediment buffer in the upper shoreface. The results presented in this paper intend to contribute to the assessment of Sand Groynes as a commonly applied nourishment method to maintain sandy coastlines. The morphological evolution of the Sand Groynes has been monitored by regularly conducting bathymetry surveys, resulting in a series of available bathymetry surveys. It is observed that the Sand Groynes have been redistributed in the alongshore, mainly in northward direction driven by dominant southwesterly wave conditions. Furthermore, data analysis suggests that Sand Groynes have a trapping capacity for alongshore supplied sand originating from upstream located Sand Groynes. A Delft3D numerical model has been set up to verify whether the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes can be properly hindcasted. Although the model has been set up in 2DH mode, hindcast results show good agreement with the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes based on field data. Trends of alongshore redistribution of Sand Groynes are well reproduced. Still the model performance could be improved, for instance by implementation of 3D velocity patterns and by a more accurate schematization of sediment characteristics. Keywords: Sand Groyne, Delfland Coast, sand nourishment, sediment transport, Delft3D INTRODUCTION Objective The main objective of this paper is to asses an innovative sand nourishment method to maintain a sandy coastline, by constructing small sandy headlands in the upper shoreface called Sand Groynes (see Figure 1). -

The Open Ocean

THE OPEN OCEAN Grade 5 Unit 6 THE OPEN OCEAN How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? What do we mean by the “open ocean”? How do we describe the open oceans of Hawai’i? The World’s Oceans The ocean is the world’s largest habitat. It covers about 70% of the Earth’s surface. Scientists divide the ocean into two main zones: Pelagic Zone: The open ocean that is not near the coast. pelagic zone Benthic Zone: The ocean bottom. benthic zone Ocean Zones pelagic zone Additional Pelagic Zones Photic zone Aphotic zone Pelagic Zones The Hawaiian Islands do not have a continental shelf Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore : anything over 500 meters from shore Inshore Ecosystems Offshore Ecosystems Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Questions 1.) How much of the Earth is covered by the ocean? Answer: 70% of the Earth is covered by ocean water. Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Questions 2.) What are the two MAIN zones of the ocean? Answer: Pelagic Zone-the open ocean not near the coast. Benthic Zone-ocean bottom. Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Questions 3.) What are some other zones within the Pelagic Zone or Open Ocean? Answer: Photic zone- where sunlight penetrates Aphotic zone- where sunlight cannot penetrate Neritic zone- over the continental shelf Oceanic zone- beyond the continental shelf Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Questions 4.) What is inshore? What is offshore? Answer: Inshore: anything within 100 meters of shore Offshore: anything over 500 meters from shore . -

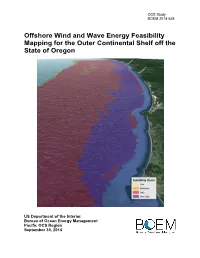

Offshore Wind and Wave Energy Feasibility Mapping for the Outer Continental Shelf Off the State of Oregon

OCS Study BOEM 2014-658 Offshore Wind and Wave Energy Feasibility Mapping for the Outer Continental Shelf off the State of Oregon US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region September 30, 2014 OCS Study BOEM 2014-658 PNNL-23720 Offshore Wind and Wave Energy Feasibility Mapping for the Outer Continental Shelf off the State of Oregon Authors K Larson1 J Tagestad1 S Geerlofs1 M Sanders2 J Ahmann3 J Busch2 B Van Cleve1 1 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory 2 Oregon Wave Energy Trust 3 Parametrix Prepared Under Inter-agency Agreement M13PG00032 U.S Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region September 30, 2014 OCS Study BOEM 2014-658 DISCLAIMER REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Pacific OCS Region, Recently Completed Environmental Studies webpage at: http://www.boem.gov/Pacific-Completed-Studies/ This report can also be obtained from the National Technical Information Service; the contact information is below. US Department of Commerce National Technical Information Service 5301 Shawnee Rd. Springfield, VA 22312 Phone: (703) 605-6000, 1(800)553-6847 Fax: (703) 605-6900 Website: http://www.ntis.gov/ CITATION K Larson, J Tagestad, S Geerlofs, M Sanders, J Ahmann, J Busch, B Van Cleve. 2014. Offshore Wind and Wave Energy Feasibility Mapping for the Outer Continental Shelf off the State of Oregon. US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Pacific OCS Region, Camarillo, CA. OCS Study BOEM 2014-658. -

Wave-Driven Circulation Patterns in the Lee of Groynes

ARTICLE IN PRESS Continental Shelf Research ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]] Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Continental Shelf Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/csr Wave-driven circulation patterns in the lee of groynes Charitha Pattiaratchi Ã, Dale Olsson 1, Yasha Hetzel, Ryan Lowe School of Environmental Systems Engineering, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: Surf zone drifters and a current meter were used to study the nearshore circulation patterns in the lee of Received 15 December 2008 groynes at Cottesloe Beach and City Beach in Western Australia. The circulation patterns revealed that a Received in revised form persistent re-circulation cell was present in the lee of the groyne which was driven by changes in wave 4 April 2009 set-up resulting from lower wave heights in the lee of the groyne. The re-circulation consisted of a Accepted 10 April 2009 longshore current directed towards the groyne which was deflected offshore due to groyne resulting in a rip current along the groyne face. The offshore-flowing rip current and the incoming waves converged at Keywords: the offshore extent of this circulation cell, with the deflection of the rip current parallel to the shoreline Groynes and then completing the recirculation through an onshore component. The Eulerian measurements Circulation revealed that 55% of the currents on the lee side of the groyne were directed offshore and that these Lagrangian currents had a maximum speed of 2 m sÀ1. Spectral analysis of the wave heights and the currents Drifters Numerical modelling revealed several corresponding peaks in the measured spectral densities with timescales between 12 s Western Australia and 50 min. -

Oceans: Submarine Relief and Water Circulation

MODULE - 3 Ocean: Submarine Relief and Water Circulation The domain of the water on the Earth 8 Notes OCEANS: SUBMARINE RELIEF AND WATER CIRCULATION Water is important for life on the earth. It is required for all life processes, such as, cell growth, protein formation, photosynthesis and, absorption of material by plants and animals. There are some living organisms, which can survive without air but none can survive without water. All the water present on the earth makes up the hydrosphere. The water in its liquid state as in rivers, lakes, wells, springs, seas and oceans; in its solid state, in the form of ice and snow, though in its gaseous state the water vapour is a constituent of atmosphere yet it also forms a part of the hydrosphere. Oceans are the largest water bodies in the hydrosphere. In this lesson we will study about ocean basins, their relief, causes and effects of circulation of ocean waters and importance of oceans for man. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to : identify various oceans and continents on the world map; differentiate the various submarine relief features; analyze the important factors determining the distribution of temperature both horizontally and vertically in oceans; locate the areas of high and low salinity on the world map and give reasons for the variation in the distribution of salinity in ocean waters; state the three types of ocean movements - waves, tides and currents; explain the formation of waves; 136 GEOGRAPHY Ocean: Submarine Relief and Water Circulation MODULE - 3 The domain of the give various factors responsible for the occurrence of tides; water on the Earth establish relationship between the planetary winds and circulation of ocean currents; explain with suitable examples the importance of oceans to mankind with special reference to the significance of continental shelves for human beings . -

Deep-Ocean Basins

Chapter23 The Ocean Basins ChapterCh t Outline Outli ne 1 ● The Water Planet Divisions of the Global Ocean Exploration of the Ocean 2 ● Features of the Ocean Floor Continental Margins Deep-Ocean Basins 3 ● Ocean-Floor Sediments Sources of Deep Ocean– Basin Sediments Physical Classification of Sediments Why It Matters Oceans cover more than 70 percent of Earth’s surface. Oceans interact with the atmosphere to influence weather and climate. Exploring and analyzing data about the chemistry of ocean water, the geology of the ocean floor, marine ecosystems, and the physics of water movement is critical to understanding natural processes on Earth. 634 Chapter 23 hhq10sena_obacho.inddq10sena_obacho.indd 663434 PDF 88/1/08/1/08 11:09:46:09:46 PPMM Inquiry Lab 20 min Sink or Float? Fill the bottom half of 3-L soda bottle with water to within about 3 inches from the top and place it on a plastic or metal tray to catch any spills. Using small (3-oz) plastic cups, with some paper clips and metal nuts for ballast, see if you can get a cup to sink with air still trapped inside, simulating a submersible. You may need something pointed to make holes in the cups. Questions to Get You Started 1. What is buoyancy and why is it so important for maritime travel? 2. Compare techniques for sinking the cup. Does one method consistently work better than others? 3. What challenges do engineers face when designing submersibles? 635 hhq10sena_obacho.inddq10sena_obacho.indd 663535 PDF 88/1/08/1/08 11:09:58:09:58 PPMM These reading tools will help you learn the material in this chapter. -

Let's Bet on Sediments!

Deep East 2001 Exploration Let’s Bet on Sediments! FOCUS Part II: (per group of 2-4) Sediments of Hudson Canyon 3 large jars with lids (e.g. Snapple bottles) 1/2 cup of each of the 3 various sediments (peb- GRADE LEVEL bles, sand, silt) 9 - 12 Water - enough to fill the 3 large jars 1 Sediment Analysis Worksheet FOCUS QUESTION 1 Stop watch How is sediment size related to the amount of time 1 Magnifying glass the sediment is suspended in water? 1 plastic spoon LEARNING OBJECTIVES Part III Demonstration Extension: Students will be able to investigate and analyze the pat- 1-10 gallon aquarium terns of sedimentation in the Hudson Canyon. 1/2 cup of each of the 3 various sediments used Students will observe how heavier particles sink in Activity One faster than finer particles. Water - enough to fill the aquarium 1 hair dryer Students will learn that submarine landslides (trench 1 aquarium filter slope failure) are avalanches of sediment in deep ocean canyons. AUDIO/VISUAL EQUIPMENT Overhead Projector for Part I Students will infer that the passive side of a conti- nental margin is not as geologically quiet as previ- TEACHING TIME ously thought. One 45-minute period ADAPTATIONS FOR DEAF STUDENTS SEATING ARRANGEMENT Teaching Time: Cooperative groups of two to four • Two 45-minute periods MAXIMUM NUMBER OF STUDENTS MATERIALS 30 Part I: Exploring Ocean Frontiers: Hudson Canyon over- KEY WORDS head. Turbidites Sedimentation Sediments 1 Deep East 2001 – Grades 9-12 Deep East 2001 – Grades 9-12 Focus: Sediments of Hudson Canyon oceanexplorer.noaa.gov oceanexplorer.noaa.gov Focus: Sediments of Hudson Canyon North American Plate are trapped within these three zones (R. -

1 OCEANOGRAPHY the PACIFIC OCEAN by PROF. A. BALSUBRAMANIAN OUTLINE 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Geographic Setting 1.2 Dimension

OCEANOGRAPHY THE PACIFIC OCEAN BY PROF. A. BALSUBRAMANIAN OUTLINE 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Geographic setting 1.2 Dimension 1.3 Depth 1.4 Principal Arms 1.5 Volume of water 2.0 Historical explorations 3.0 Crustal plates 4.0 Profile of the ocean floor 4.1 Continental shelf 4.2 Continental slope 4.3 Submarine canyons 4.4 Deep ocean floor 4.5 Abyssal plains/hills 4.6 Ring of Fire 4.7 Mid ocean ridges 4.8 Deep ocean trenches 4.9 Seamounts 4.10 Guyots 4.11 Icebergs 4.12 Active volcanoes 4.13 Islands or island arcs 5.0 Sedimentation 6.0 Water masses and Temperature 6.1 Salinity 6.2 Density 7.0 Climate 7.1 Water circulation and Ocean Currents 7.2 Oceanic currents 7.3 Ocean waves 8.0 Ecological zones 8.1 Marine fauna 8.2 Marine flora 8.3 Marine sediments 9.0 Economic mineral resources 9.1 Commerce and shipping 9.2 Ports and terminals 10.0 Marine pollution 10.1 Hazards 1 The Objectives After attending this lesson, the learner should be able to comprehend about the geographic setting of the Pacific ocean, its dimension, associated water masses, morphological features of the ocean floor, very significant conditions of the ocean, sediments, marine life, marine pollution and other hazards. In addition the user should be able to understand, the importance of the Pacific in the context of global activities including the historical oceanographic explorations. 1.0 Introduction The world’s oceanic water masses occupy about 97 per cent of the hydrosphere.