Richard Jefferies. a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE FORWARD PARTY: the PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS BA, U Niversityof B Ritish

'THE FORWARD PARTY: THE PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE'UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June, 1Q68 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by h.ils representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date June 17, 1968. "... today's journalism is tomorrow's history." - William Manchester TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page PREFACE viii I. THE PALL MALL GAZETTE; 1865-1880 1 Origins of the P.M.G 1 The paper's early days 5" The "Amateur Casual" 10 Greenwood's later paper . 11 Politics 16 Public acceptance of the P.M.G. ...... 22 George Smith steps down as owner 2U Conclusion 25 II. NEW MANAGEMENT 26 III. JOHN MORLEY'S PALL MALL h$ General tone • U5> Politics 51 Conclusion 66 IV. WILLIAM STEAD: INFLUENCES THAT SHAPED HIM . 69 iii. V. THE "NEW JOURNALISM" 86 VI. POLITICS . 96 Introduction 96 Political program 97 Policy in early years 99 Campaigns: 188U-188^ and political repercussion -:-l°2 The Pall Mall opposes Gladstone's first Home Rule Bill. -

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912 Kate Tryon The RICHARD JEFFERIES SOCIETY (Registered Charity No. 1042838) was founded in 1950 to promote appreciation and study of the writings of Richard Jefferies (1848-1887). Website http://richardjefferiessociety.co.uk email [email protected] 01793 783040 The Kate Tryon manuscript In 2010, the Richard Jefferies Society published Kate Tryon’s memoir of her first visit to Jefferies’ Land in 1910. [Adventures in the Vale of the White Horse: Jefferies Land, Petton Books.] It was discovered that the author and artist had started work on another manuscript in 1912 entitled “Walks in Jefferies-Land”. However, this type-script was incomplete and designed to illustrate the places that Mrs Tryon had visited and portrayed in her oil-paintings using Jefferies’ own words. There are many pencilled-in additions to this type-script in Kate Tryon’s own hand- writing and selected words are underlined in red crayon. Page 13 is left blank, albeit that the writer does not come across as a superstitious person. The Jefferies’ quotes used are not word-perfect; neither is her spelling nor are her facts always correct. There is a handwritten note on the last page that reads: “This is supposed to be about half the book. – K.T.” The Richard Jefferies Society has edited the “Walks”, correcting obvious errors but not the use of American spelling in the main text. References for quotes have been added along with appropriate foot-notes. The Richard Jefferies Society is grateful to Kate Schneider (Kate Tryon’s grand- daughter) for allowing the manuscripts to be published and thanks Stan Hickerton and Jean Saunders for editing the booklet. -

"Radwayv Ants of Stalwart Republican Diva, Do "No; to a Press Correspondent by Travellers the by a Band of Required a Reputation Throughout the State

A Lire. A lapartsrnt ArrawC. MATTERS IN AFGHANISTAN. Singer' B.iRTiioLDrsnia OFFICIAL. FIRE IN ALBANY. uihl. The fo of mwploious upon It neeragM s eep, creates' WEEK. Mme. Kilsson imparted to the PaU The Met 11. a the it a charaetw THE has Preudirr for fences sp th ya-te- 1 bis general moVamenta or com an appetite, Bald lVdeMal and. appearicei I by a Wall Fall- The Ameer to Have Little Faith Mall some interesting facta about cora-rlet- and renewed WllA I'oar firemen Burled Oauttt The BnrtholJi pedestal fuudfnrla nearly i. pnmonship, without waiting until be bai England or If the result. In the United States and the ing apon Thru, Iu .Russia. a ilnger'a lite. She says: The statuj has arrived nnd soon New robbed a traveler, fired a houso, ot murdered ink. Cl: ,.! In Albany, N. V., recently, Burch's stablu The London Standard prints advices from a "1 am obliged to go to bed as early as York harbor will be grace 1 by the inostmag-hirlce-n a fellow-ma- is an important function of "Every cloud ha a lUves ever seen. ind Gray's piano factory were burned. Four reliable source in India in regard to recent possible after singing, and evert Oti 'oil rvlotnal statu the world has shrewd detective. Even more imXrtant it liulng.." Old World. Enllghtenint; that World t" Wha the an-w- t of a which, If not checked. in frontier nights' am retire as early as "I.ilrty diease firemen were buried under fulliug wulls, aitd event eennection with the Afghan ordered to a priceless blesiing poraonrtl liberty fs. -

Journalist: the Americanization of W.T

A ‘New’ Journalist: The Americanization of W.T. Stead Helena Goodwyn ABSTRACT W. T. Stead, the journalist and editor, is known primarily for his knight-errant crusade on behalf of women and girls in the sensational investigative articles ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ (1885). The controversial success of these articles could not have been achieved without Stead’s study and adoption of American journalistic techniques. Stead’s importance to nineteenth century periodicals must be informed by an understanding of Stead as a mediating force between British and American print culture. This premise is developed here through exploration of the terms ‘New Journalism’ and ‘Americanization’. Drawing from every stage of his career including his amateur yet dynamic beginnings as an unpaid contributor to the Northern Echo, I will examine Stead’s unofficial title as the father of New Journalism and the extent to which this title is directly attributable to his relationship with America, or, to use Stead’s term, his Americanization. Keywords: New Journalism, W.T. Stead, America, international, popular journalism, Americanization, Transatlantic, Britain, newspapers 1. INTRODUCTION For the journalist and editor W.T. Stead there could never be enough information about American life and culture printed in British periodicals. At the outset of his transition from apprenticed clerk to the world of newspapers, in 1870, we find him complaining to John Copleston, then editor of the Northern Echo, about the lack of American news published by the periodical press. In this letter we also witness an early glimpse of Stead’s life-long aspiration for Anglo-American amity: ‘I wish we had more American news in our papers. -

Friend Or Femme Fatale?: Olga Novikova in the British Press, 1877-1925

FRIEND OR FEMME FATALE?: OLGA NOVIKOVA IN THE BRITISH PRESS, 1877-1925 Mary Mellon A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Louise McReynolds Donald J. Raleigh Jacqueline M. Olich i ABSTRACT MARY MELLON: Friend or Femme Fatale?: Olga Novikova in the British Press, 1877-1925 (Under the direction of Dr. Louise McReynolds) This thesis focuses on the career of Russian journalist Olga Alekseevna Novikova (1840-1925), a cosmopolitan aristocrat who became famous in England for her relentless advocacy of Pan-Slavism and Russian imperial interests, beginning with the Russo- Turkish War (1877-78). Using newspapers, literary journals, and other published sources, I examine both the nature of Novikova’s contributions to the British press and the way the press reacted to her activism. I argue that Novikova not only played an important role in the production of the discourse on Russia in England, but became an object of that discourse as well. While Novikova pursued her avowed goal of promoting a better understanding between the British and Russian empires, a fascinated British press continually reinterpreted Novikova’s image through varying evaluations of her nationality, gender, sexuality, politics and profession. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS FRIEND OR FEMME FATALE?: OLGA NOVIKOVA IN THE BRITISH PRESS, 1877-1925……………….…………...……………………….1 Introduction……………………………………………………………….1 The Genesis of a “Lady Diplomatist”…………………………………...11 Novikova Goes to War…………………………………………………..14 Novikova After 1880…………………………………………………….43 Conclusion……………………………………………………………….59 Epilogue: The Lady Vanishes..………………………………………….60 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………….63 iii The removal of national misunderstandings is a task which often baffles the wisdom of the greatest statesmen, and defies the effort of the most powerful monarchs. -

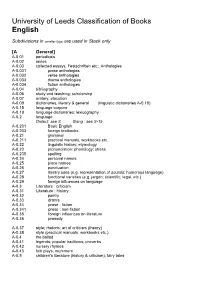

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

A 'New'journalist: the Americanization of WT Stead

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Northumbria Research Link Citation: Goodwyn, Helena (2018) A ‘New’ Journalist: The Americanization of W. T. Stead. Journal of Victorian Culture, 23 (3). pp. 405-420. ISSN 1355-5502 Published by: Taylor & Francis URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcy038 <https://doi.org/10.1093/jvcult/vcy038> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/43774/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) A ‘New’ Journalist: The Americanization of W.T. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2015 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

19Th Century British Library Newspapers 17Th and 18Th Century Burney Collection Newspapers

Burney Collection These collections are brought to you by Users will have quick access to Burney’s newspapers and news Gale, through an exclusive partnership pamphlets from a wide-range of news sources including more than with the British Library. 38,000 pages from the London Evening Post, early issues of the Boston and Virginia Gazettes, plus countless journals and annuals. The online pages date as far back as 1603 and continue through to Coverage includes everything from well- the early 19th century. A sampling of the 1,270 titles included are: known historic events and cultural icons 19th Century British Library Newspapers of the time – to sporting events, arts, Athenian Gazette or Casuistical Mercury, 1691 culture and other national pastimes. Bath Chronicle, 1784 th th Some of the most popular newspapers 17 and 18 Century Burney Collection Newspapers include: Daily Courant, 1702 brought to you by Gale, publisher of The Times Digital Archive Daily Gazetteer, 1735 • Daily News • Morning Chronicle Daily Post, 1719 • Illustrated Police News Dublin Mercury, 1769 • The Chartist Grub Street Journal, 1730 • The Era • The Belfast News–Letter London Evening Post, 1727 • The Caledonian Mercury London Gazette, 1666 • The Aberdeen Journal Mercurius Politicus Comprising the Summ of All Intelligence, 1650 Ask us about these related digital collections: • The Leeds Mercury Morning Chronicle, 1770 th • The Exeter Flying Post The Economist Historical Archive 1843–2003 19 Century U.K. Periodicals: Series 1: New Readerships Morning Post, 1773 The Times Digital Archive, 1785–1985 19th Century U.K. Periodicals: Series 2: Empire New England Courant, 1721 North Briton, 1762 About Gale Digital Collections: Oracle, 1790 These two exciting collections are part of Gale Digital Collections, the world’s largest scholarly primary source online library. -

107-128 Andrew Lang, Comparative Anthropology

http://akroterion.journals.ac.za ANDREW LANG, COMPARATIVE ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE CLASSICS IN THE AFRICAN ROMANCES OF RIDER HAGGARD J L Hilton (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban) The long-standing friendship between Andrew Lang (1844-1912)1 and Henry Rider Haggard (1856-1925)2 is surely one of the most intriguing literary relationships of the Victorian era.3 Lang was a pre-eminent literary critic and his support for Haggard’s earliest popular romances, such as King Solomon’s mines (1885) and She (1887), helped to establish them as leading models of the new genre of imperial adventure fiction.4 Lang and Haggard co-authored The world’s desire (1890)5 and the ideas of Lang, who was also a brilliant Classics scholar, can be seen in many of Haggard’s works. There are some significant similarities between the two men: both were approximate contemporaries who lived through the most aggressive phase of British imperialism, both were highly successfully writers who earned their living by their pens, both wrote prolifically and fluently on a wide 1 On Andrew Lang, see Donaldson 2004:453-456, Langstaff 1978, De Cocq 1968, Gordon 1928, and, above all, Green 1946. 2 The standard biographies of Rider Haggard are Etherington 1984, and Cohen 1960, somewhat dated, but very well written, but note also the more specialised studies of Stiebel 2009, 2001, Coan 2007, 2000, 1997, Monsman 2006, Pocock 1993, Fraser 1998, Vogelsberger 1984, Higgins 1981, Lewis 1984:128-132, Ellis 1978, and Bursey 1973. I owe special thanks to the local experts on Haggard, Lindy Stiebel and Stephen Coan. -

Berkeley. Excerpt Dracula

! Bram Stoker Dracula 1897 ! ! ! ! Chapter Seventeen ! ! Dr. Seward's Diary (continued) 1 When we arrived at the Berkeley Hotel, Van Helsing found a telegram waiting for him:— ! “Am coming up by train. Jonathan at Whitby. Important news.—MINA HARKER.” ! The Professor was delighted. “Ah, that wonderful Madam Mina,” he said, “pearl among women! She ! arrive, but I cannot stay. She must go to your house, friend John. You must meet her at the station. Telegraph 5 her en route, so that she may be prepared.” ! When the wire was despatched he had a cup of tea; over it he told me of a diary kept by Jonathan ! Harker when abroad, and gave me a typewritten copy of it, as also of Mrs. Harker’s diary at Whitby. “Take ! these,” he said, “and study them well. When I have returned you will be master of all the facts, and we can ! then better enter on our inquisition. Keep them safe, for there is in them much of treasure. You will need all 10 your faith, even you who have had such an experience as that of to-day. What is here told,” he laid his hand ! heavily and gravely on the packet of papers as he spoke, “may be the beginning of the end to you and me and ! many another; or it may sound the knell of the Un-Dead who walk the earth. Read all, I pray you, with the ! open mind; and if you can add in any way to the story here told do so, for it is all-important. -

Spring 2012 Thejservingournal Professional Journalism Since 1912 Institute Salutes a Pioneer of Investigative Journalism

Magazine of the Chartered Institute of Journalists Spring 2012 TheJServingournal professional journalism since 1912 Institute salutes a pioneer of investigative journalism s interest surrounding the sinking of the Titanic reaches Aa crescendo point for the April centenary of the disaster, the Chartered Institute of Journalists will conduct its own ceremony of remembrance for one of the greatest journalists of all time who perished when the “unsinkable” ship sank. William Thomas Stead, one-time editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, died as he sailed to answer a personal invitation from US President William Howard Taft to speak at a congress in New York’s Carnegie Hall on world peace and international arbitration. He decided to treat himself to a £26 11s (£25.55) first class ticket on the liner’s maiden voyage. He was 62 when he died. The Institute, led by President Norman Bartlett, will lay a wreath at the Stead memorial on London’s Victoria Embankment, directly opposite the Temple tube station’s Embankment exit, at 10am on Sunday, April 15. This will be followed by a special service at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, at 11am. Drinks will be served afterwards. Journalists responded in their droves to a “shilling and half-crown appeal” to erect a All members of the Institute who can memorial to W T Stead, on the Victoria Embankment, opposite the Temple tube station. attend are being urged to do so because A second casting was erected in New York’s Central Park. The inscription reads: “W. T. not only is this “our” event but the Stead, 1849 – 1912.