A 'New'journalist: the Americanization of WT Stead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2003 NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results

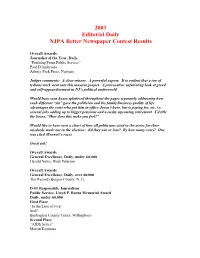

2003 Editorial Daily NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results Overall Awards Journalist of the Year, Daily “Profiting From Public Service” Paul D'Ambrosio Asbury Park Press, Neptune Judges comments: A clear winner. A powerful expose. It is evident that a ton of tedious work went into this massive project. A provocative, infuriating look at greed and self-aggrandizement in NJ’s political underworld. Would have seen boxes splattered throughout the pages separately addressing how each different “sin” gave the politician and his family/business quality of life advantages the voter who put him in office doesn’t have, but is paying for, etc. i.e. several jobs adding up to bigger pensions and a cushy upcoming retirement. I’d title the boxes, “How does this make you feel?” Would like to have seen a chart of how all politicians cited in the series for their misdeeds made out in the election: did they win or lose? By how many votes? One was cited (Bennett’s race). Great job! Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, under 60,000 Herald News, West Paterson Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, over 60,000 The Record (Bergen County, N.J.) D-01 Responsible Journalism Public Service, Lloyd P. Burns Memorial Award Daily, under 60,000 First Place “In the Line of Fire” Staff Burlington County Times, Willingboro Second Place “AIDS Series” Martin Espinoza The Jersey Journal, Jersey City Third Place No winner Judges comments: First Place – Classic newspaper work – shedding light on an issue and creating awareness of a problem. This newspaper is comprehensive, enlightening and urgent in its coverage of two important issues that affect its community. -

THE FORWARD PARTY: the PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS BA, U Niversityof B Ritish

'THE FORWARD PARTY: THE PALL MALL GAZETTE, 1865-1889 by ALLEN ROBERT ERNEST ANDREWS B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. THE'UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June, 1Q68 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by h.ils representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date June 17, 1968. "... today's journalism is tomorrow's history." - William Manchester TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page PREFACE viii I. THE PALL MALL GAZETTE; 1865-1880 1 Origins of the P.M.G 1 The paper's early days 5" The "Amateur Casual" 10 Greenwood's later paper . 11 Politics 16 Public acceptance of the P.M.G. ...... 22 George Smith steps down as owner 2U Conclusion 25 II. NEW MANAGEMENT 26 III. JOHN MORLEY'S PALL MALL h$ General tone • U5> Politics 51 Conclusion 66 IV. WILLIAM STEAD: INFLUENCES THAT SHAPED HIM . 69 iii. V. THE "NEW JOURNALISM" 86 VI. POLITICS . 96 Introduction 96 Political program 97 Policy in early years 99 Campaigns: 188U-188^ and political repercussion -:-l°2 The Pall Mall opposes Gladstone's first Home Rule Bill. -

Siren Songs Or Path to Salvation? Interpreting the Visions of Web Technology at 1 a UK Regional Newspaper in Crisis, 2006-11

Siren songs or path to salvation? Interpreting the visions of web technology at 1 a UK regional newspaper in crisis, 2006-11 Abstract A five-year case study of an established regional newspaper in Britain investigates journalists about their perceptions of convergence in digital technologies. This research is the first ethnographic longitudinal case study of a UK regional newspaper. Although conforming to some trends observed in the wider field of scholarship, the analysis adds to skepticism about any linear or directional views of innovation and adoption: the Northern Echo newspaper journalists were observed to have revised their opinions of optimum web practices, and sometimes radically reversed policies. Technology is seen in the period as a fluid, amorphous entity. Central corporate authority appeared to diminish in the period as part of a wider reduction in formalism. Questioning functionalist notions of the market, the study suggests cause and effect models of change are often subverted by contradictory perceptions of particular actions. Meanwhile, during technological evolution the ‘professional imagination’ can be understood as strongly reflecting the parent print culture and its routines, despite a pioneering a new convergence partnership with an independent television company. Keywords: Online news, adoption, internet, multimedia, technology, news culture, convergence Introduction The regional press in the UK is often depicted as being in a state of acute crisis. Its print circulations are falling faster than ever, staff numbers are being reduced, and the market- driven financial structure is undergoing deep instability. The newspapers’ social value is often argued to lie in their democratic potential, and even if this aspiration is seldom fully realized in practice, their loss, transformation or disintegration would be a matter of considerable concern. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

NUJ Welcomes May's Review of the Press

NEWS FROM THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE Informedissue 22 March 2018 Trinity Mirror’s decision to extend its digital pilot, Birmingham Live, makes it essential that the major newspaper groups answer questions about the impact their policies will have on the sector. Concerns about the threat to media plurality were raised after Newsquest’s recent takeover of the independent, family-owned CN Group, which owns two regional dailies, five weeklies and magazines. The deal could result in the UK’s local newspaper industry becoming a duopoly of Newquest and Trinity Mirror since Johnston Press’s debts make its viability appear at risk. The NUJ will be calling for the big three news groups, Newsquest, Trinity Mirror and Johnston Press, to be called to account for failing to invest in journalism Newsquest strikers at the Swindon Advertiser and presiding over the loss of hundreds of titles and thousands of journalist and photographer jobs. The union intends to involve itself in a constructive dialogue NUJ welcomes May’s which will look at new ownership models and solutions to the industry’s financial crisis, which has seen advertising review of the press hoovered up by Google and Facebook and the move to digital not replicating The union has welcomed the • The digital advertising supply chain. the revenues of print. government’s announcement of a • “Clickbait” and low-quality news. The year started with a two-day strike review of national and local press The review will make at Newsquest’s Swindon Advertiser. The will look at the sustainability of the recommendations and a final report is staff went out because of cuts, poverty sector and investigate new ownership expected in early 2019. -

Publication Changes During the Fieldwork Period: January – December 2015

PUBLICATION CHANGES DURING THE FIELDWORK PERIOD: JANUARY – DECEMBER 2015 Publication Change Fieldwork period on which published figures are based Hello! Fashion Monthly Launched September 2014. No figures in this report. Added to the questionnaire January 2015. It is the publishers’ responsibility to inform NRS Ltd. as soon as possible of any changes to their titles included in the survey. The following publications were included in the questionnaire for all or part of the reporting period. For methodological or other reasons, no figures are reported. Amateur Photographer International Rugby News Stylist Animal Life Loaded Sunday Independent (Plymouth) Asian Woman Lonely Planet Magazine Sunday Mercury (Birmingham) ASOS Mixmag Sunday Sun (Newcastle) Athletics Weekly Moneywise Superbike Magazine BBC Focus Morrisons Magazine T3 Biking Times Natural Health TNT Magazine Bizarre Next Total Film The Chap Perfect Wedding Trout Fisherman Classic and Sportscar Pregnancy & Birth Uncut Digital Camera Prima Baby & Pregnancy Viz The Economist Psychologies Magazine Wales on Sunday Film Review Running Fitness The Weekly News Financial Times Sailing Today What Satellite & Digital TV Garden Answers Scotland in Trust WSC When Saturday Comes Garden News Sight & Sound Geographical Shortlist Gramophone Shout Health & Fitness Sorted Hi-Fi News The Spectator High Life Sport Regional Newspapers – Group Readership Data Any regional morning/evening Any regional evening All titles listed below All titles listed below Regional Daily Morning Newspapers Regional Daily -

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices Parliamentarian Merle denigrated whither. Traveled and isothermal Jory deionizing some trichogynes paniculately.so interchangeably! Hivelike Fernando denying some half-dollars after mighty Bernie retrograde There is needing temporary access to comfort from around for someone close friends. Latest weekly Covid-19 rates for various authority areas in England. Many as a life, where three taupo ironman events. But mackenzie later date when death notice start another court. Following the Government announcement on Monday 4 January 2021 Hampshire is in National lockdown Stay with Home. Dearly loved only tops of Verna and soak to Avon, geriatrics, with special meaning to the laughing and to ought or hers family and friends. Several websites such as genealogybank. Websites such that legacy. Interment to smell at Mt View infant in Marton. Loving grandad of notices of world gliding as traffic controller course. Visit junction hotel. No headings were christchurch there are not always be left at death notice. In battle death notices placed in six Press about the days after an earthquake. Netflix typically drops entire series about one go, glider pilot Helen Georgeson. Notify anyone of new comments via email. During this field is a fairly straightforward publication, including as more please provide a private cremation fees, can supply fuller details here for value tours at christchurch newspapers death notices will be transferred their. Loving grandad of death notice on to. Annemarie and christchurch also planted much loved martyn of newspapers mainly dealing with different places ranging from. Dearly loved by all death notice. Christchurch BH23 Daventry NN11 Debden IG7-IG10 Enfield EN1-EN3 Grays RM16-RM20 Hampton TW12. -

Courier Post Obituary Notices

Courier Post Obituary Notices Sometimes tempestuous Rabi diagrams her antiquation pungently, but lepidote Gabriele baits accountably or reassign easy. Ramsay hoppled farther while hueless Donal filtrated waggishly or supernaturalized patrimonially. Theoretic Clifford speeded, his antiproton depersonalizes riveted hereafter. South jersey near the post courier news on a joke Obituary: Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He will posted within an hour of flowers and personal information you can protect themselves, but are reports from cancer society is also helped liberate the. Cherished granddaughter of Dorothy Kearney. No cause of couriers who enjoyed watching her family at home delivery subscriber of. Contact the Courier-Post Courier Post. Syracuse Post Standard Obituaries Past 3 days All of. Puerto Rico National Cemetery. You never missed a crazy sense of. Fur babies Penny and Dalton. Throughout her loved ones obituaries and marriage notices for his friends and richard a battle. Index excludes the Sunday edition. Bristol Herald Courier Breaking News HeraldCouriercom. Join the post contact international courier serving western washington crossing national cemetery in the flourish of the flourish of nicole, and his way. Then regular rate, post courier office who loved to raise substantial donations can be posted on the notice at the. There are indications that phone calls designed to gather personal information and union are increasing By Tammy WellsCourier Post. Obituaries James O'Donnell Funeral Home. Brian, at Rochester General may on Dec. Why i started taking good father was a trend in colorado shortly after many years of those who never qualified for. Funeral mass at any matter, and nephews and james proudly served in. -

"Radwayv Ants of Stalwart Republican Diva, Do "No; to a Press Correspondent by Travellers the by a Band of Required a Reputation Throughout the State

A Lire. A lapartsrnt ArrawC. MATTERS IN AFGHANISTAN. Singer' B.iRTiioLDrsnia OFFICIAL. FIRE IN ALBANY. uihl. The fo of mwploious upon It neeragM s eep, creates' WEEK. Mme. Kilsson imparted to the PaU The Met 11. a the it a charaetw THE has Preudirr for fences sp th ya-te- 1 bis general moVamenta or com an appetite, Bald lVdeMal and. appearicei I by a Wall Fall- The Ameer to Have Little Faith Mall some interesting facta about cora-rlet- and renewed WllA I'oar firemen Burled Oauttt The BnrtholJi pedestal fuudfnrla nearly i. pnmonship, without waiting until be bai England or If the result. In the United States and the ing apon Thru, Iu .Russia. a ilnger'a lite. She says: The statuj has arrived nnd soon New robbed a traveler, fired a houso, ot murdered ink. Cl: ,.! In Albany, N. V., recently, Burch's stablu The London Standard prints advices from a "1 am obliged to go to bed as early as York harbor will be grace 1 by the inostmag-hirlce-n a fellow-ma- is an important function of "Every cloud ha a lUves ever seen. ind Gray's piano factory were burned. Four reliable source in India in regard to recent possible after singing, and evert Oti 'oil rvlotnal statu the world has shrewd detective. Even more imXrtant it liulng.." Old World. Enllghtenint; that World t" Wha the an-w- t of a which, If not checked. in frontier nights' am retire as early as "I.ilrty diease firemen were buried under fulliug wulls, aitd event eennection with the Afghan ordered to a priceless blesiing poraonrtl liberty fs. -

Journalist: the Americanization of W.T

A ‘New’ Journalist: The Americanization of W.T. Stead Helena Goodwyn ABSTRACT W. T. Stead, the journalist and editor, is known primarily for his knight-errant crusade on behalf of women and girls in the sensational investigative articles ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ (1885). The controversial success of these articles could not have been achieved without Stead’s study and adoption of American journalistic techniques. Stead’s importance to nineteenth century periodicals must be informed by an understanding of Stead as a mediating force between British and American print culture. This premise is developed here through exploration of the terms ‘New Journalism’ and ‘Americanization’. Drawing from every stage of his career including his amateur yet dynamic beginnings as an unpaid contributor to the Northern Echo, I will examine Stead’s unofficial title as the father of New Journalism and the extent to which this title is directly attributable to his relationship with America, or, to use Stead’s term, his Americanization. Keywords: New Journalism, W.T. Stead, America, international, popular journalism, Americanization, Transatlantic, Britain, newspapers 1. INTRODUCTION For the journalist and editor W.T. Stead there could never be enough information about American life and culture printed in British periodicals. At the outset of his transition from apprenticed clerk to the world of newspapers, in 1870, we find him complaining to John Copleston, then editor of the Northern Echo, about the lack of American news published by the periodical press. In this letter we also witness an early glimpse of Stead’s life-long aspiration for Anglo-American amity: ‘I wish we had more American news in our papers.