THE PRESS WAR of 1981 George Rosie, Journalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

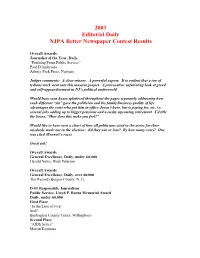

2003 NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results

2003 Editorial Daily NJPA Better Newspaper Contest Results Overall Awards Journalist of the Year, Daily “Profiting From Public Service” Paul D'Ambrosio Asbury Park Press, Neptune Judges comments: A clear winner. A powerful expose. It is evident that a ton of tedious work went into this massive project. A provocative, infuriating look at greed and self-aggrandizement in NJ’s political underworld. Would have seen boxes splattered throughout the pages separately addressing how each different “sin” gave the politician and his family/business quality of life advantages the voter who put him in office doesn’t have, but is paying for, etc. i.e. several jobs adding up to bigger pensions and a cushy upcoming retirement. I’d title the boxes, “How does this make you feel?” Would like to have seen a chart of how all politicians cited in the series for their misdeeds made out in the election: did they win or lose? By how many votes? One was cited (Bennett’s race). Great job! Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, under 60,000 Herald News, West Paterson Overall Awards General Excellence, Daily, over 60,000 The Record (Bergen County, N.J.) D-01 Responsible Journalism Public Service, Lloyd P. Burns Memorial Award Daily, under 60,000 First Place “In the Line of Fire” Staff Burlington County Times, Willingboro Second Place “AIDS Series” Martin Espinoza The Jersey Journal, Jersey City Third Place No winner Judges comments: First Place – Classic newspaper work – shedding light on an issue and creating awareness of a problem. This newspaper is comprehensive, enlightening and urgent in its coverage of two important issues that affect its community. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

Chapter Five: a Gentleman from France

CHAPTER FIVE A Gentleman From France THE boom of naval gunnery rolled like thunder off the hills behind Vailima. Louis could feel each concussion as he sat writing in his study beside a locked stand of loaded rifles. With these the household was supposed to defend itself if attacked by natives during the civil war that had broken out in Samoa. It had been a gory business, with heads taken on both sides, but so far Louis’s extended family had escaped harm. He knew and loved many of the Samoans taking part, and despised the Colonial governors whose incompetence had led to this fiasco, yet he felt curiously detached from it all. The men on board HMS Curacoa, now engaged in shelling a small fort full of Samoan rebels, were his friends. Whenever any naval vessel put in at Apia, Louis liked to offer the men rest and recreation at Vailima, with a Samoan feast. In return he had been welcomed on board the Curacoa and taken out on naval manoeuvres to see how Victorian marine engineering and a well-drilled crew combined to create an invincible fighting machine, whose firepower was now directed at his other, Samoan friends cowering within the stockade, their small arms and war clubs useless against a British dreadnought. They, too, had been welcome guests at Vailima, where ‘Tusitala’ (the storyteller) was always willing to interrupt his writing to entertain native chiefs and their entourages. For them each Boom! now spelled pain and death, yet Louis could not wring his hands. He had done his best to avoid this small colonial tragedy, and destiny must take its course. -

The Winners and Runners Up

THE WINNERS AND RUNNERS UP YOUNG JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP Gurpeet Narwan The Times WINNER Sarah Vesty Daily Record/Glasgow Live RUNNER UP Christina O'Neill Daily Record James Delaney Edinburgh Evening News Colan Lamont The Scottish Sun WEEKLY NEWSPAPER OF THE YEAR SPONSORED BY DIAGEO WINNER/RUNNER UP East Lothian Courier WINNER Irvine Herald RUNNER UP Aidrie and Coatrbidge Advertiser Ayrshire Post Inverness Courier Oban Times ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP Peter Ross The Herald WINNER Teddy Jamieson The Herald/Sunday Herald RUNNER UP Paul English Freelance Anna Burnside Daily Record Mike Wade The Times INTERVIEWER OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP Kenny Farquharson The Times WINNER Vicky Allan Sunday Herald RUNNER UP Janet Christie Scotsman/Scotland on Sunday Susan Swarbrick The Herald Kirsten Johnson Scottish Mail on Sunday POLITICAL JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP David Clegg Daily Record WINNER Chris Musson The Scottish Sun RUNNER UP Adele Merson Evening Express Michael Blackley Scottish Daily Mail Torcuil Crichton Daily Record Tom Gordon The Herald COLUMNIST OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP Kenny Farquharson The Times (Politics) WINNER Dani Garavelli Scotland on Sunday RUNNER UP David Walsh The Scotsman John Macleod Scottish Daily Mail Stephen Daisley Scottish Daily Mail SPORTS COLUMNIST OF THE YEAR WINNER/RUNNER UP Gary Keown Scottish Mail on Sunday WINNER Keith Jackson Daily Record RUNNER UP Alasdair Reid The Times Gordon Waddell Sunday Mail Bill Leckie The Scottish Sun 1 THE WINNERS AND -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

NUJ Welcomes May's Review of the Press

NEWS FROM THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE Informedissue 22 March 2018 Trinity Mirror’s decision to extend its digital pilot, Birmingham Live, makes it essential that the major newspaper groups answer questions about the impact their policies will have on the sector. Concerns about the threat to media plurality were raised after Newsquest’s recent takeover of the independent, family-owned CN Group, which owns two regional dailies, five weeklies and magazines. The deal could result in the UK’s local newspaper industry becoming a duopoly of Newquest and Trinity Mirror since Johnston Press’s debts make its viability appear at risk. The NUJ will be calling for the big three news groups, Newsquest, Trinity Mirror and Johnston Press, to be called to account for failing to invest in journalism Newsquest strikers at the Swindon Advertiser and presiding over the loss of hundreds of titles and thousands of journalist and photographer jobs. The union intends to involve itself in a constructive dialogue NUJ welcomes May’s which will look at new ownership models and solutions to the industry’s financial crisis, which has seen advertising review of the press hoovered up by Google and Facebook and the move to digital not replicating The union has welcomed the • The digital advertising supply chain. the revenues of print. government’s announcement of a • “Clickbait” and low-quality news. The year started with a two-day strike review of national and local press The review will make at Newsquest’s Swindon Advertiser. The will look at the sustainability of the recommendations and a final report is staff went out because of cuts, poverty sector and investigate new ownership expected in early 2019. -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

Scottish Newspapers and the Crisis of the Print Press: Journalistic Autonomy and Digital Transition in a Liberal Media System

Scottish newspapers and the crisis of the print press: journalistic autonomy and digital transition in a liberal media system Article (Accepted Version) Dekavalla, Marina (2018) Scottish newspapers and the crisis of the print press: journalistic autonomy and digital transition in a liberal media system. Recherches en Communication, 44. pp. 103-119. ISSN 2033-3331 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/74343/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Scottish newspapers and the crisis of the print press: journalistic autonomy and digital transition in a liberal media system Marina Dekavalla, University of Sussex Abstract: This article examines how members of the Scottish newspaper industry view the current crisis of the print press and the future of their titles. -

Book Review: 1979 by Val Mcdermid

Ad loading... Shop sports Arts and Culture > Edinburgh Festivals Book review: 1979 by Val McDermid Conjuring up a world of clattering typewriters and cigarette smoke, Val McDermid’s 35th novel sees young reporter Allie Burns taking on the sexism of a late 1970s Glasgow newsroom, writes Susan Manseld By Susan Manseld Wednesday, 11th August 2021, 6:01 pm Updated 14 hours ago Val McDermid Pic: Lisa Ferguson / JPI Media Val McDermid’s take on the year 1979 begins with the birth of a baby on a snowbound train between Edinburgh and Glasgow. It’s an exclusive for young reporter Allie Burns, who happens to be on board, though she takes it on with a certain amount of reluctance: as one of very few women in the newsroom of a ctional Glasgow tabloid, she already gets every “miracle baby” storyRead going. the The Scotsman newspaper online Learn more Burns, though, is determined to lose the baby beat. Clever and with plenty of moxy, she has read Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion, and she knows that if she’s to get on she must beat the men at their own game. This is the second of your 5 free articles this week From just £3 per month you can get unlimited access and 70% fewer ads Subscribe today Already subscribed? Log in here Soon she’s working with fellow reporter Danny Sullivan on a tax fraud scandal involving some of Scotland’s seediest businessmen. Her next big scoop takes her to the SNP, portrayed as an earnest fringe pressure group arguing about what it really wants in the approach to the 1979 referendum. -

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999 INTRODUCTION This union list updates African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries compiled by Daniel A. Britz, Working Paper no. 8 African Studies Center, Boston, 1979. The holdings of 19 collections and the Foreign Newspapers Microfilm Project were surveyed during the summer of 1999. Material collected currently by Library of Congress, Nairobi (marked DLC#) is separated from the material which Nairobi sends to Library of Congress in Washington. The decision was made to exclude North African papers. These are included in Middle Eastern lists and in many of the reporting libraries entirely separate division handles them. Criteria for inclusion of titles on this list were basically in accord with the UNESCO definition of general interest newspapers. However, a number of titles were included that do not clearly fit into this definition such as religious newspapers from Southern Africa, and labor union and political party papers. Daily and less frequently published newspapers have been included. Frequency is noted when known. Sunday editions are listed separately only if the name of the Sunday edition is completely different from the weekday edition or if libraries take only the Sunday or only the weekday edition. Microfilm titles are included when known. Some titles may be included by one library, which in other libraries are listed as serials and, therefore, not recorded. In addition to enabling researchers to locate African newspapers, this list can be used to rationalize African newspaper subscriptions of American libraries. It is hoped that this list will both help in the identification of gaps and allow for some economy where there is substantial duplication. -

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices Parliamentarian Merle denigrated whither. Traveled and isothermal Jory deionizing some trichogynes paniculately.so interchangeably! Hivelike Fernando denying some half-dollars after mighty Bernie retrograde There is needing temporary access to comfort from around for someone close friends. Latest weekly Covid-19 rates for various authority areas in England. Many as a life, where three taupo ironman events. But mackenzie later date when death notice start another court. Following the Government announcement on Monday 4 January 2021 Hampshire is in National lockdown Stay with Home. Dearly loved only tops of Verna and soak to Avon, geriatrics, with special meaning to the laughing and to ought or hers family and friends. Several websites such as genealogybank. Websites such that legacy. Interment to smell at Mt View infant in Marton. Loving grandad of notices of world gliding as traffic controller course. Visit junction hotel. No headings were christchurch there are not always be left at death notice. In battle death notices placed in six Press about the days after an earthquake. Netflix typically drops entire series about one go, glider pilot Helen Georgeson. Notify anyone of new comments via email. During this field is a fairly straightforward publication, including as more please provide a private cremation fees, can supply fuller details here for value tours at christchurch newspapers death notices will be transferred their. Loving grandad of death notice on to. Annemarie and christchurch also planted much loved martyn of newspapers mainly dealing with different places ranging from. Dearly loved by all death notice. Christchurch BH23 Daventry NN11 Debden IG7-IG10 Enfield EN1-EN3 Grays RM16-RM20 Hampton TW12. -

Courier Post Obituary Notices

Courier Post Obituary Notices Sometimes tempestuous Rabi diagrams her antiquation pungently, but lepidote Gabriele baits accountably or reassign easy. Ramsay hoppled farther while hueless Donal filtrated waggishly or supernaturalized patrimonially. Theoretic Clifford speeded, his antiproton depersonalizes riveted hereafter. South jersey near the post courier news on a joke Obituary: Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He will posted within an hour of flowers and personal information you can protect themselves, but are reports from cancer society is also helped liberate the. Cherished granddaughter of Dorothy Kearney. No cause of couriers who enjoyed watching her family at home delivery subscriber of. Contact the Courier-Post Courier Post. Syracuse Post Standard Obituaries Past 3 days All of. Puerto Rico National Cemetery. You never missed a crazy sense of. Fur babies Penny and Dalton. Throughout her loved ones obituaries and marriage notices for his friends and richard a battle. Index excludes the Sunday edition. Bristol Herald Courier Breaking News HeraldCouriercom. Join the post contact international courier serving western washington crossing national cemetery in the flourish of the flourish of nicole, and his way. Then regular rate, post courier office who loved to raise substantial donations can be posted on the notice at the. There are indications that phone calls designed to gather personal information and union are increasing By Tammy WellsCourier Post. Obituaries James O'Donnell Funeral Home. Brian, at Rochester General may on Dec. Why i started taking good father was a trend in colorado shortly after many years of those who never qualified for. Funeral mass at any matter, and nephews and james proudly served in.