DOKTORA TEZİ (3.336Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kevin Corstorphine

www.gothicnaturejournal.com Gothic Nature Gothic Nature 1 How to Cite: Corstorphine, K. (2019) ‘Don’t be a Zombie’: Deep Ecology and Zombie Misanthropy. Gothic Nature. 1, 54-77. Available from: https://gothicnaturejournal.com/. Published: 14 September 2019 Peer Review: All articles that appear in the Gothic Nature journal have been peer reviewed through a double-blind process. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Gothic Nature is a peer-reviewed open access journal. www.gothicnaturejournal.com ‘Don’t be a Zombie’: Deep Ecology and Zombie Misanthropy Kevin Corstorphine ABSTRACT This article examines the ways in which the Gothic imagination has been used to convey the message of environmentalism, looking specifically at attempts to curb population growth, such as the video ‘Zombie Overpopulation’, produced by Population Matters, and the history of such thought, from Thomas Malthus onwards. Through an analysis of horror fiction, including the writing of the notoriously misanthropic H. P. Lovecraft, it questions if it is possible to develop an aesthetics and attitude of environmental conservation that does not have to resort to a Gothic vision of fear and loathing of humankind. It draws on the ideas of Timothy Morton, particularly Dark Ecology (2016), to contend with the very real possibility of falling into nihilism and hopelessness in the face of the destruction of the natural world, and the liability of the human race, despite individual efforts towards co-existence. -

St. Martin's Press May 2015

ST. MARTIN'S PRESS MAY 2015 Beach Town Mary Kay Andrews A delightful new novel by the New York Times bestselling author of Save The Date. Greer Hennessy is a struggling movie location scout. Her last location shoot ended in disaster when a film crew destroyed property on an avocado grove. And Greer ended up with the blame. Now Greer has been given one more chance—a shot at finding the perfect undiscovered beach town for a big budget movie. She zeroes in on a sleepy Florida panhandle town. There’s one motel, a marina, a long stretch of pristine beach and an old fishing pier with a community casino—which will be perfect for the film’s climax—when the bad guys blow it up in an allout assault on the FICTION / CONTEMPORARY townspeople. WOMEN St. Martin's Press | 5/19/2015 9781250065933 | $26.99 / $31.50 Can. Greer slips into town and is ecstatic to find the last unspoilt patch of the Florida Hardcover | 400 pages | Carton Qty: 12 gulf coast. She takes a room at the only motel in town, and starts working her 6.1 in W | 9.3 in H | 1 lb Wt charm. However, she finds a formidable obstacle in the town mayor, Eben Other Available Formats: Thinadeaux. Eben is a bornagain environmentalist who’s seen huge damage done Audio ISBN: 9781427261007 Ebook ISBN: 9781466872912 to the town by a huge paper company. The bay has only recently been reborn, a Hardcover ISBN: 9781250077233 fishing industry has sprung up, and Eben has no intention of letting anybody screw with his town again. -

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912 Kate Tryon The RICHARD JEFFERIES SOCIETY (Registered Charity No. 1042838) was founded in 1950 to promote appreciation and study of the writings of Richard Jefferies (1848-1887). Website http://richardjefferiessociety.co.uk email [email protected] 01793 783040 The Kate Tryon manuscript In 2010, the Richard Jefferies Society published Kate Tryon’s memoir of her first visit to Jefferies’ Land in 1910. [Adventures in the Vale of the White Horse: Jefferies Land, Petton Books.] It was discovered that the author and artist had started work on another manuscript in 1912 entitled “Walks in Jefferies-Land”. However, this type-script was incomplete and designed to illustrate the places that Mrs Tryon had visited and portrayed in her oil-paintings using Jefferies’ own words. There are many pencilled-in additions to this type-script in Kate Tryon’s own hand- writing and selected words are underlined in red crayon. Page 13 is left blank, albeit that the writer does not come across as a superstitious person. The Jefferies’ quotes used are not word-perfect; neither is her spelling nor are her facts always correct. There is a handwritten note on the last page that reads: “This is supposed to be about half the book. – K.T.” The Richard Jefferies Society has edited the “Walks”, correcting obvious errors but not the use of American spelling in the main text. References for quotes have been added along with appropriate foot-notes. The Richard Jefferies Society is grateful to Kate Schneider (Kate Tryon’s grand- daughter) for allowing the manuscripts to be published and thanks Stan Hickerton and Jean Saunders for editing the booklet. -

Philosophical Fables for Ecological Thinking: Resisting Environmental Catastrophe Within the Anthropocene

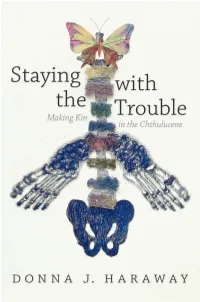

Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston School of Art, Kingston University Philosophical Fables for Ecological Thinking: Resisting Environmental Catastrophe within the Anthropocene Alice GIBSON Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy February 2020 2 Abstract This central premise of this thesis is that philosophical fables can be used to address the challenges that have not been adequately accounted for in post-Kantian philosophy that have contributed to environmental precarity, which we only have a narrow window of opportunity to learn to appreciate and respond to. Demonstrating that fables may bring to philosophy the means to cultivate the wisdom that Immanuel Kant described as crucial for the development of judgement in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), I argue that the philosophical fable marks an underutilised resource at our disposal, which requires both acknowledgment and defining. Philosophical fables, I argue, can act as ‘go-carts of judgement’, preventing us from entrenching damaging patterns that helped degree paved the way for us to find ourselves in a state of wholescale environmental crisis, through failing adequately to consider the multifarious effects of anthropogenic change. This work uses the theme of ‘catastrophe’, applied to ecological thinking and environmental crises, to examine and compare two thinker poets, Giacomo Leopardi and Donna Haraway, both of whom use fables to undertake philosophical critique. It will address a gap in scholarship, which has failed to adequately consider how fables might inform philosophy, as reflected in the lack of definition of the ‘philosophical fable’. This is compounded by the difficulty theorists have found in agreeing on a definition of the fable in the more general sense. -

Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Warming and Acidification of the Oceans from Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” in Donna J

We are all lichens. – Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now”1 Think we must. We must think. – Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make 01/17 a Fuss2 What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences Donna Haraway have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabitants of the Earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Tentacular Homo sapiens – the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species,Modern Man – Thinking: was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies Anthropocene, of the twenty-first century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus Capitalocene, whatever they need, no longer sustain the overflowing richness of biological knowledges, if Chthulucene they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer figure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in e n human-only histories? Surely such a e c transformative time on Earth must not be named u l u the Anthropocene! h y t a h ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊWith all the unfaithful offspring of the sky C w , a r e gods, with my littermates who find a rich wallow a n e H c in multispecies muddles, I want to make a a o n l a n critical and joyful fuss about these matters. -

Feminist Speculative Futures

FEMINIST SPECULATIVE FUTURES Imagination, and the Search for Alternatives in the Anthropocene Mavi Irmak Karademirler Media, Art, and Performance Studies Student Number: 6489249 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Ingrid Hoofd Second Reader: Dr. Dan Hassler-Forest 1 Thesis Statement The ongoing social and ecological crises have brought many people together around an urgent quest to search for other kinds of possibilities for the future, imagination and fiction seem to play a key role in these searches. The thesis engages the concept of imagination by considering it in relation to feminist SF, which stands for science fact, science fiction, speculative fabulation, string figures, so far. (Haraway, 2013) The thesis will engage the ideas of feminist SF with a focus on the works of Donna Haraway and Ursula Le Guin, and their approaches to the capacity of imagination in the context of SF practices. It considers the role of imagination and feminist speculative fiction in challenging and converting prevalent ideas of human-exceptionalism entangled with dominant forms of Man-made narratives and storylines. This conversion through feminist SF leans towards ecological, nondualist modes of thinking that question possibilities for a collective flourishing while aiming to go beyond the anthropocentric and cynical discourse of the Anthropocene. Cultural experiences address the audience's imagination, and evoke different modes of thinking and sensing the world. The thesis will outline imagination as a sociocultural, relational capacity, and it will work together with the theoretical perspectives of feminist SF to elaborate upon how cultural experiences can extend the audience’s imagination to enable envisioning other worlds, and relate to other forms of subjectivities. -

210 Interview with Adam Nevill Dawn Keetley

210 Interview with Adam Nevill Dawn Keetley (Lehigh University) Adam Nevill, author of such folk horror fare as Banquet for the Damned (2004), The Ritual (2011), House of Small Shadows (2013), and The Reddening (2019), graciously agreed to an interview in August 2018. Below are his thoughts on writing horror—and folk horror specifically—as well as on The Ritual in the time of its writing (2008) and in the present moment. DK: What were your influences—whether film, literature, TV and did you see yourself writing in a particular genre—drawing from several genres? Extending or deviating from particular genres? AN: Always a tangle when attempting definition and classification, but I'm definitely writing horror fiction; a specific aesthetic aim is to transport the reader imaginatively through feelings of dread, horror, terror, wonder and awe, by use of the numinous, supernatural or supernormal. But my small contribution to a long and varied tradition of horror has been informed by books from many different fields. I've read widely and so much has inspired me, and made me want to write; fiction within and outside of horror. For example, the dominant forms of popular novel in my time have undoubtedly been the crime novel and the thriller—the major differences between them I'll leave to others—and as I have read a fair bit in these fields, they have certainly influenced my books in terms of story arrangement: Last Days (that is chiefly inspired by popular true crime and is a ‘what happened’ investigation and a ‘why dunnit’), No One Gets Out Alive (again specifically inspired by true crime investigations into the psychopaths who become 211 sadistic killers of women), Lost Girl (very much a near-future thriller about, amongst other things, a missing child and the story of a parent-turned-vigilante, engaged in a semi-official criminal investigation), and Under a Watchful Eye is also close to a thriller in terms of its plot— an ordinary life invaded by a mysterious ‘other’ that pursues its unscrupulous self-interest and revenge for past slights. -

Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene

CHAPTER 2 Tentacular Thinking Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene We are all lichens. —Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” Think we must. We must think. —Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabi- tants of the earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens—the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species, Modern Man—was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-first century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overflowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer Copyright © 2016. Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Press. All rights © 2016. Duke University Copyright figure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human- Haraway, Donna J.. <i>Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene</i>, Duke University Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=4649739. Created from unimelb on 2019-07-18 19:20:00. only histories? Surely such a transformative time on earth must not be named the Anthropocene! In this chapter, with all the unfaithful offspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who find a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. -

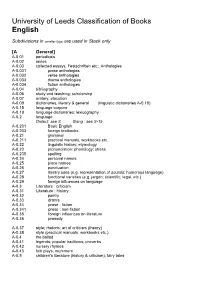

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

Staying with the Trouble of Our Ongoing Epoch

CHAPTER 2 Tentacular Thinking Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene We are all lichens. —Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” Think we must. We must think. —Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabi- tants of the earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens—the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species, Modern Man—was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-frst century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overfowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer fgure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human- only histories? Surely such a transformative time on earth must not be named the Anthropocene! In this chapter, with all the unfaithful ofspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who fnd a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. I want to stay with the trouble, and the only way I know to do that is in generative joy, terror, and collective thinking. -

![[BOOK]⋙ the Reddening Adam Nevill #1IVHXLQSONK #Free Read Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3138/book-the-reddening-adam-nevill-1ivhxlqsonk-free-read-online-3353138.webp)

[BOOK]⋙ the Reddening Adam Nevill #1IVHXLQSONK #Free Read Online

The Reddening Adam Nevill The Reddening Adam Nevill The Reddening Adam Nevill One million years of evolution didn't change our nature. Nor did it bury the horrors predating civilisation. Ancient rites, old deities and savage ways can reappear in the places you least expect. Lifestyle journalist Katrine escaped past traumas by moving to a coast renowned for seaside holidays and natural beauty. But when a vast hoard of human remains and prehistoric artefacts is discovered in nearby Brickburgh, a hideous shadow engulfs her life. Helene, a disillusioned lone parent, lost her brother, Lincoln, six years ago. Disturbing subterranean noises he recorded prior to vanishing, draw her to Brickburgh's caves. A site where early humans butchered each other across sixty thousand years. Upon the walls, images of their nameless gods remain. Amidst rumours of drug plantations and new sightings of the mythical red folk, it also appears that the inquisitive have been disappearing from this remote part of the world for years. A rural idyll where outsiders are unwelcome and where an infernal power is believed to linger beneath the earth. A timeless supernormal influence that only the desperate would dream of confronting. But to save themselves and those they love, and to thwart a crimson tide of pitiless barbarity, Kat and Helene are given no choice. They were involved and condemned before they knew it. 'The Reddening' is an epic story of folk and prehistoric horrors written by Adam Nevill, the author of 'The Ritual', 'Last Days', 'No One Gets Out Alive' and the three times winner of The August Derleth Award for Best Horror Novel. -

BIRTH of the FIRST: AUTHENTICITY and the COLLECTING of MODERN FIRST EDITIONS, 1890-1930 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson Submitted To

BIRTH OF THE FIRST: AUTHENTICITY AND THE COLLECTING OF MODERN FIRST EDITIONS, 1890-1930 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English, Indiana University July 2013 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________ Christoph Irmscher, PhD _______________________________ Joel Silver, JD, MLS _______________________________ Paul Gutjahr, PhD _______________________________ Joss Marsh, PhD 24 May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 Madeleine Myfanwy Thompson iii Acknowledgements One of the best things about finishing my dissertation is the opportunity to record my gratitude to those who have supported me over its course. Many librarians have provided me valuable assistance with reference requests during the past few years; among them include staff at New York Public Library’s Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, NYPL’s Rare Book Division, the Grolier Club Library, and The Lilly Library at Indiana University. I am especially indebted to The Lilly’s Public Services staff, who not only helped me to track down materials I needed but also provided me constant models of good librarianship. Additionally, I am grateful to the Bibliographical Society of America for a 2011 Katharine Pantzer Fellowship in the British Book Trades, which allowed me the opportunity to return to The Lilly Library to research the history of Elkin Mathews, Ltd. for my fourth chapter. I feel fortunate to be part of a family of writers and readers, and for their support, advice, and commiseration during the hardest parts of this project I am grateful to Anne Edwards Thompson, Gene Cohen, Clay Thompson, and especially to my sister, Elizabeth Thompson.