Expeditions JONATHAN PRATT Hidden Peak 1994 & Makalu 1995 Two First British Ascents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expeditions & Treks 2008/2009

V4362_JG_Exped Cover_AW 1/5/08 15:44 Page 1 Jagged Globe NEW! Expeditions & Treks www.jagged-globe.co.uk Our new website contains detailed trip itineraries 2008 for the expeditions and treks contained in this brochure, photo galleries and recent trip reports. / 2009 You can also book securely online and find out about new trips and offers by subscribing to our email newsletter. Jagged Globe The Foundry Studios, 45 Mowbray Street, Sheffield S3 8EN United Kingdom Expeditions Tel: 0845 345 8848 Email: [email protected] Web: www.jagged-globe.co.uk & Treks Cover printed on Take 2 Front Cover: Offset 100% recycled fibre Mingma Temba Sherpa. sourced only from post Photo: Simon Lowe. 2008/2009 consumer waste. Inner Design by: pages printed on Take 2 www.vividcreative.com Silk 75% recycled fibre. © 2007 V4362 V4362_JG_Exped_Bro_Price_Alt 1/5/08 15:10 Page 2 Ama Dablam Welcome to ‘The Matterhorn of the Himalayas.’ Jagged Globe Ama Dablam dominates the Khumbu Valley. Whether you are trekking to Everest Base Camp, or approaching the mountain to attempt its summit, you cannot help but be astounded by its striking profile. Here members of our 2006 expedition climb the airy south Expeditions & Treks west ridge towards Camp 2. See page 28. Photo: Tom Briggs. The trips The Mountains of Asia 22 Ama Dablam: A Brief History 28 Photo: Simon Lowe Porter Aid Post Update 23 Annapurna Circuit Trek 30 Teahouses of Nepal 23 Annapurna Sanctuary Trek 30 The Seven Summits 12 Everest Base Camp Trek 24 Lhakpa Ri & The North Col 31 The Seven Summits Challenge 13 -

DEATH ZONE FREERIDE About the Project

DEATH ZONE FREERIDE About the project We are 3 of Snow Leopards, who commit the hardest anoxic high altitude ascents and perform freeride from the tops of the highest mountains on Earth (8000+). We do professional one of a kind filming on the utmost altitude. THE TRICKIEST MOUNTAINS ON EARTH NO BOTTLED OXYGEN CHALLENGES TO HUMAN AND NATURE NO EXTERIOR SUPPORT 8000ERS FREERIDE FROM THE TOPS MOVIES ALONE WITH NATURE FREERIDE DESCENTS 5 3 SNOW LEOS Why the project is so unique? PROFESSIONAL FILMING IN THE HARDEST CONDITIONS ❖ Higher than 8000+ m ❖ Under challenging efforts ❖ Without bottled oxygen & exterior support ❖ Severe weather conditions OUTDOOR PROJECT-OF-THE-YEAR “CRYSTAL PEAK 2017” AWARD “Death zone freeride” project got the “Crystal Peak 2017” award in “Outdoor project-of-the-year” nomination. It is comparable with “Oscar” award for Russian outdoor sphere. Team ANTON VITALY CARLALBERTO PUGOVKIN LAZO CIMENTI Snow Leopard. Snow Leopard. Leader The first Italian Snow Leopard. MC in mountaineering. Manaslu of “Mountain territory” club. Specializes in a ski mountaineering. freeride 8163m. High altitude Ski-mountaineer. Participant cameraman. of more than 20 high altitude expeditions. Mountains of the project Manaslu Annapurna Nanga–Parbat Everest K2 8163m 8091m 8125m 8848m 8611m The highest mountains on Earth ❖ 8027 m Shishapangma ❖ 8167 m Dhaulagiri I ❖ 8035 m Gasherbrum II (K4) ❖ 8201 m Cho Oyu ❖ 8051 m Broad Peak (K3) ❖ 8485 m Makalu ❖ 8080 m Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak, K5) ❖ 8516 m Lhotse ❖ 8091 m Annapurna ❖ 8586 m Kangchenjunga ❖ 8126 m Nanga–Parbat ❖ 8614 m Chogo Ri (K2) ❖ 8156 m Manaslu ❖ 8848 m Chomolungma (Everest) Mountains that we climbed on MANASLU September 2017 The first and unique freeride descent from the altitude 8000+ meters among Russian sportsmen. -

Pakistan 1995

LINDSAY GRIFFIN & DAVID HAMILTON Pakistan 1995 Thanks are due to Xavier Eguskitza, Tafeh Mohammad andAsem Mustafa Awan for their help in providing information. ast summer in the Karakoram was one of generally unsettled weather L conditions. Intermittent bad weather was experienced from early June and a marked deterioration occurred from mid-August. The remnants of heavy snow cover from a late spring fall hampered early expeditions, while those arriving later experienced almost continuous precipitation. In spite of these difficulties there was an unusually high success rate on both the 8000m and lesser peaks. Pakistan Government statistics show that 59 expe ditions from 16 countries received permits to attempt peaks above 6000m. Of the 29 expeditions to 8000m peaks 17 were successful. On the lower peaks II of the 29 expeditions succeeded. There were 14 fatalities (9 on 8000m peaks) among the 384 foreign climbers; a Pakistani cook and porter also died in separate incidents. The action of the Pakistan Government in limiting the number of per mits issued for each of the 8000m peaks to six per season has led to the practice of several unconnected expeditions 'sharing' a permit, an un fortunate development which may lead to complicated disputes with the Pakistani authorities in the future. Despite the growing commercialisation of high-altitude climbing, there were only four overtly commercial teams on the 8000m peaks (three on Broad Peak and one on Gasherbrum II). However, it is clear that many places on 'non-commercial' expeditions were filled by experienced climbers able to supply substantial funds from their own, or sponsors', resources. -

K2 Base Camp and Gondogoro La Trek

K2 And Gondogoro La Trek, Pakistan This is a trekking holiday to K2 and Concordia in the Karakoram Mountains of Pakistan followed by crossing the Gondogoro La to Hushe Valley to complete a superb mountaineering journey. Group departures See trip’s date & cost section Holiday overview Style Trek Accommodation Hotels, Camping Grade Strenuous Duration 23 days from Islamabad to Islamabad Trekking / Walking days On Trek: 15 days Min/Max group size 1 / 8. Guaranteed to run Meeting point Joining in Islamabad, Pakistan Max altitude 5,600m, Gondogoro Pass Private Departures & Tailor Made itineraries available Departures Group departures 2021 Dates: 20 Jun - 12 Jul 27 Jun - 19 Jul 01 Jul - 23 Jul 04 Jul - 26 Jul 11 Jul - 02 Aug 18 Jul - 09 Aug 25 Jul - 16 Aug 01 Aug - 23 Aug 08 Aug - 30 Aug 15 Aug - 06 Sep 22 Aug - 13 Sep 29 Aug - 20 Sep Will these trips run? All our k2 and Gondogoro la treks are guaranteed to run as schedule. Unlike some other companies, our trips will take place with a minimum of 1 person and maximum of 8. Best time to do this Trek Pakistan is blessed with four season weather, spring, summer, autumn and winter. This tour itinerary is involved visiting places where winter is quite harsh yet spring, summer and autumns are very pleasant. We recommend to do this Trek between June and September. Group Prices & discounts We have great range of Couple, Family and Group discounts available, contact us before booking. K2 and Gondogoro trek prices are for the itinerary starting from Islamabad to Skardu K2 - Gondogoro Pass - Hushe Valley and back to Islamabad. -

Brief Description of the Northern Areas

he designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do T not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN Pakistan. Copyright: ©2003 Government of Pakistan, Northern Areas Administration and IUCN–The World Conservation Union. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holders, providing the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of the publication for resale or for other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Citation: Government of Pakistan and IUCN, 2003. Northern Areas State of Environment and Development. IUCN Pakistan, Karachi. xlvii+301 pp. Compiled by: Scott Perkin Resource person: Hamid Sarfraz ISBN: 969-8141-60-X Cover & layout design: Creative Unit (Pvt.) Ltd. Cover photographs: Gilgit Colour Lab, Hamid Sarfraz, Khushal Habibi, Serendip and WWF-Pakistan. Printed by: Yaqeen Art Press Available from: IUCN–The World Conservation Union 1 Bath Island Road, Karachi Tel.: 92 21 - 5861540/41/42 Fax: 92 21 - 5861448, 5835760 Website: www.northernareas.gov.pk/nassd N O RT H E R N A R E A S State of Environment & Development Co n t e n t s Acronyms and Abbreviations vi Glossary -

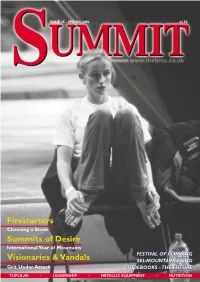

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

Appalachia Alpina

Appalachia Volume 71 Number 2 Summer/Fall 2020: Unusual Pioneers Article 16 2020 Alpina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Alpina," Appalachia: Vol. 71 : No. 2 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia/vol71/iss2/16 This In Every Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Appalachia by an authorized editor of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alpina A semiannual review of mountaineering in the greater ranges The 8,000ers The major news of 2019 was that Nirmal (Nims) Purja, from Nepal, climbed all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks in under seven months. The best previous time was a bit under eight years. Records are made to be broken, but rarely are they smashed like this. Here, from the Kathmandu Post, is the summary: Annapurna, 8,091 meters, Nepal, April 23 Dhaulagiri, 8,167 meters, Nepal, May 12 Kangchenjunga, 8,586 meters, Nepal, May 15 Everest, 8,848 meters, Nepal, May 22 Lhotse, 8,516 meters, Nepal, May 22 Makalu, 8,481 meters, Nepal, May 24 Nanga Parbat, 8,125 meters, Pakistan, July 3 Gasherbrum I, 8,080 meters, Pakistan, July 15 Gasherbrum II, 8,035 meters, Pakistan, July 18 K2, 8,611 meters, Pakistan, July 24 Broad Peak, 8,047 meters, Pakistan, July 26 Cho Oyu 8,201 meters, China/Nepal, September 23 Manaslu, 8,163 meters, Nepal, September 27 Shishapangma, 8,013 meters, China, October 29 He reached the summits of Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu in an astounding three days. -

Lhotse 8,516M / 27,939Ft

LHOTSE 8,516M / 27,939FT 2022 EXPEDITION TRIP NOTES LHOTSE EXPEDITION TRIP NOTES 2022 EXPEDITION DETAILS Dates: April 9 to June 3, 2022 Duration: 56 days Departure: ex Kathmandu, Nepal Price: US$35,000 per person On the summit of Lhotse Photo: Guy Cotter During the spring season of 2022, Adventure Consultants will operate an expedition to climb Lhotse, the world’s 4th highest mountain. Lhotse sits alongside and in the shadow of its more famous partner, Mount Everest, which is possibly THE ADVENTURE CONSULTANTS why it receives a relatively low number of ascents. Lhotse’s climbing route follows the same line LHOTSE TEAM of ascent as Everest to just below the South Col LOGISTICS where we break right to continue up the Lhotse Face and into Lhotse’s summit couloir. The narrow With technology constantly evolving, Adventure couloir snakes for 600m/2,000ft, all the way to the Consultants have kept abreast of all the new lofty summit. techniques and equipment advancements which encompass the latest in weather The climb will be operated alongside the Adventure forecasting facilities, equipment innovations and Consultants Everest team and therefore will enjoy communications systems. the associated infrastructure and legendary Base Camp support. Adventure Consultants expedition staff, along with the operations and logistics team at the head Lhotse is a moderately difficult mountain due to office in New Zealand, provide the highest level of its very high altitude; however, the climbing is backup and support to the climbing team in order sustained and never too complicated or difficult. to run a flawless expedition. This is coupled with It is a perfect peak for those who want to climb at a very strong expedition guiding team and Sherpa over 8,000m in a premier location! contingent who are the most competent and experienced in the industry. -

{Download PDF} Conquistadors of the Useless : from the Alps To

CONQUISTADORS OF THE USELESS : FROM THE ALPS TO ANNAPURNA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lionel Terray | 464 pages | 07 May 2020 | Vertebrate Publishing | 9781912560219 | English | United Kingdom Conquistadors of the Useless : From the Alps to Annapurna PDF Book A warm feeling of happiness flows through my body; ecstatic, I feel as if I were floating in this vast infinitude. Olivier Coudurier and Nil Prasad Gurung reached the top at After another climb to camps 3 and 4, they descend again to base camp to prepare for the final climb. He made first ascents in the Alps, Alaska, the Andes, and the Himalaya. This book is really about Terray's great alpine exploits in Europe, the Himalayas and the Andes. All of the pages are intact and the cover is intact and the spine may show signs of wear. When the book first came out it was thought that it had been ghost written. Condition: LikeNew. He was at the centre of global mountaineering at a time when Europe was emerging from the shadow of World War II, and he surfaced as a hero. It combines the virtues of brevity and quick accessibility, yet it is an undeniably impressive-looking peak, and as the actual climbing is quite difficult it commands a high tariff. The book starts in January with a letter from Kurt Diemberger to Hermann Warth, who was living in Nepal, suggesting an expedition to Makalu "in a real small party". About Lionel Terray. You will not find them on amazon. Highly Recommended! The Kathmandu main sights are all shown. Terray sees Quebec in the pre-Quiet Revolution years from the eyes of an enlightened and enthusiastic outsider - noting "Ah, do not beg the favor of an easy life - pray to become one of the truly strong. -

The Scottish Gasherbrum III Expedition

41 The Scottish Gasherbrum III Expedition Desmond Rubens Plates 11-14 The first obstacle to setting out on a Karakorarn trip is to decide upon a suitable objective. Geoff Cohen and I spent many long hours in the SMC library, combing back numbers of journals. An 8000m peak? - attractive, undoubtedly, but in Pakistan as mobbed as the Buchaille at the Glasgow Fair. Under 8000? - definitely quieter and also cheaper. Indeed, our eventual choice, Gasherbrum Ill, at 7952m was probably the best value peak in terms of £/metre of mountain - and compare the crowds! 1985 saw eleven expeditions to Gasherbrum 11 and five to Gasherbrum I. In contrast, our expedition was only the second ever to Gasherbrum Ill. Gasherbrum III is a retiring, rather ugly mountain, hidden from the Baltoro Glacier by Gasherbrum IV and placed well up the Gasherbrum cirque when viewed from the Abruzzi glacier. Its first ascent was made in 1975 by a Polish party which included Alison Chadwick and Wanda Rutkiewicz. Their route ascended much of Gasherbrum 11, traversed beneath its summit pyramid to the snowy saddle between the two peaks and climbed a difficult summit gully. During the 1958 Gasherbrum IV expedition, Cassin 1 made a brief solo excursion from a high camp which terminated at 7300m. We were uncertain where Cassin actually went but it seemed he retreated before getting to grips with the real difficulties which lie in the last 700-800m. Thus, Gasherbrum III was virtually untouched, its secret faces and ridges well hidden from prying eyes. We were unable to obtain many useful photo graphs before we departed, though a picture from GIV in Moraini's book l showed a dolomitic-Iooking craggy aspect. -

DP Everest Tibet

EVEREST – Nordanstieg von Tibet Mount Everest Expedition von Tibet/China I. Einleitung: Mit 8850m ist der Everest knapp 250m höher als jeder andere Berg auf der Welt. Die tibetischen Anstiege von der Nordseite sind die preislich günstigsten Wege zum Gipfel, und der Nordost Grat hat sich dort wegen seiner geringen technischen Schwierigkeiten als Normalweg etabliert. Dennoch bleibt die Besteigung ein sehr ernstes Unternehmen, was nur sehr wenige Bergsteiger ohne die Benutzung von künstlichem Sauerstoff erreichen. Klettertechnisch ist dieser Aufstieg anspruchsvoller als der Süd-Anstieg von Nepal, jedoch sind die objektiven Gefahren durch Eis-Schlag und Lawinen geringer. An der Expedition nehmen nur erfahrene Höhenbergsteiger teil, wir stellen und organisieren Dein Team um die Besteigung. Unsere Erfahrung geht zurück bis 1991 als Daniel Mazur von SummitClimb sein erstes Mal den Mount Everest bestieg. Seit 2004 führten wir jedes Jahr eine Tibet Everest Expedition durch, mit Ausnahme von 2008, da wegen der Olympischen Fackelexpedition Tibet gesperrt war. John Otto, unserer Organisator in Tibet, lebt seit den 90ern in China und ist Ausbilder der CTMA, der Tibetanischen Mountaineering Association und hilft uns bei der Auswahl eines erfahrenen und freundlichen Begleitteams. Auch bringen wir Sherpas mit mehrfacher Gipfelerfahrung nach China und haben eine langjährige gute Beziehung zu unseren wichtigen Helfern vor Ort. Summit-Climb-Expeditionsleiter – Dein Team mit Everest Erfahrung! • Daniel Mazur, mehrfacher Everest Expeditionsleiter, seit 1991 (Gipfel) am Everest aktiv und einer der erfahrensten Höhenbergsteiger weltweit, verzichtete 2006 auf 8700m Höhe auf den Gipfel, um den Bergsteiger einer anderen Expedition das Leben zu retten. • Felix Berg, technisch versierter Kletterer und Bergsteiger, bestieg 2004 den Mount Everest als Expeditionsleiter und ist Allround-Bergsteiger mit umfangreicher 8000m-Erfahrung. -

The Influence of Islamic Religiosity on the Perceived Socio-Cultural Impact of Sustainable Tourism Development in Pakistan

sustainability Article The Influence of Islamic Religiosity on the Perceived Socio-Cultural Impact of Sustainable Tourism Development in Pakistan: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach 1,2, 1,2, , 3, 4,5 Jaffar Aman y , Jaffar Abbas y * , Shahid Mahmood *, Mohammad Nurunnabi and Shaher Bano 2 1 School of Media and Communication (SMC), Antai College of Economics and Management (ACEM), Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU), No. 800 Dongchuan Road Minhang District, Shanghai 200240, China 2 School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University, No. 99 Shangda Road, Baoshan, Shanghai 200444, China; Jaff[email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (S.B.) 3 College of Management, Shenzhen University, No. 3688 Nanhai Avenue, Nanshan District, Shenzhen 518060, China 4 Department of Accounting, Prince Sultan University, P.O. Box 66833, Riyadh 11586, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 5 St Antony’s College, University of Oxford, 62 Woodstock Road, Oxford OX2 6JF, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (S.M.) Jaffar Abbas and Jaffar Aman equally contributed as a first author to this work. y Received: 17 March 2019; Accepted: 16 May 2019; Published: 29 May 2019 Abstract: Typically, residents play a role in developing strategies and innovations in tourism. However, few studies have sought to understand the role of Islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan. Previous studies focusing on socio-cultural impacts as perceived by local communities have applied various techniques to explain the relationships between selected variables. Circumstantially, the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique has gained little attention for measuring the religiosity factors affecting the perceived socio-cultural impacts of sustainable tourism.