Exodus 12-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco 2018 Final

KIVUNIM Comes to Morocco March 15-28, 2018 (arriving from Spain and Portugal) PT 1 Charles Landelle-“Juive de Tanger” Unlike our astronauts who travel to "outer space," going to Morocco is a journey into "inner space." For Morocco reveals under every tree and shrub a spiritual reality that is unlike anything we have experienced before, particularly as Jewish travelers. We enter an Islamic world that we have been conditioned to expect as hostile. Instead we find a warmth and welcome that both captivates and inspires. We immediately feel at home and respected as we enter a unique multi-cultural society whose own 2011 constitution states: "Its unity...is built on the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Amazigh and Saharan-Hassani components, is nurtured and enriched by African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean constituents." A journey with KIVUNIM through Morocco is to glimpse the possibilities of the future, of a different future. At our alumni conference in December, 2015, King Mohammed VI of Morocco honored us with the following historic and challenge-containing words: “…these (KIVUNIM) students, who are members of the American Jewish community, will be different people in their community tomorrow. Not just different, but also valuable, because they have made the effort to see the world in a different light, to better understand our intertwined and unified traditions, paving the way for a different future, for a new, shared destiny full of the promises of history, which, as they have realized in Morocco, is far from being relegated to the past.” The following words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel remind us of the purpose of our travels this year. -

THE TEN PLAGUES of EGYPT: the Unmatched Power of Yahweh Overwhelms All Egyptian Gods

THE TEN PLAGUES OF EGYPT: The Unmatched Power of Yahweh Overwhelms All Egyptian Gods According to the Book of Exodus, the Ten Plagues were inflicted upon Egypt so as to entice their leader, Pharaoh, to release the Israelites from the bondages of slavery. Although disobedient to Him, the Israelites were God's chosen people. They had been in captivity under Egyptian rule for 430 years and He was answering their pleas to be freed. As indicated in Exodus, Pharaoh was resistant in releasing the Israelites from under his oppressive rule. God hardened Pharaoh's heart so he would be strong enough to persist in his unwillingness to release the people. This would allow God to manifest His unmatched power and cause it to be declared among the nations, so that other people would discuss it for generations afterward (Joshua 2:9-11, 9:9). After the tenth plague, Pharaoh relented and commanded the Israelites to leave, even asking for a blessing (Exodus 12:32) as they departed. Although Pharaoh’s hardened heart later caused the Egyptian army to pursue the Israelites to the Red Sea, his attempts to return them into slavery failed. Reprints are available by exploring the link at the bottom of this page. # PLAGUE SCRIPTURE 1 The Plague of Blood Exodus 7:14-24 2 The Plague of Frogs Exodus 7:25- 8:15 3 The Plague of Gnats Exodus 8:16-19 4 The Plague of Flies Exodus 8:20-32 5 The Plague on Livestock Exodus 9:1-7 6 The Plague of Boils Exodus 9:8-12 7 The Plague of Hail Exodus 9:13-35 8 The Plague of Locusts Exodus 10:1-20 9 The Plague of Darkness Exodus 10:21-29 10 The Plague on the Firstborn Exodus 11:1-12:30 --- The Exodus Begins Exodus 12:31-42 http://downriverdisciples.com/ten-plagues-of-egypt . -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

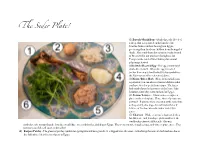

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

Parashat Bo the Women Were There Nonetheless …

WOMEN'S LEAGUE SHABBAT 2016 Dvar Torah 2 Parashat Bo The Women Were There Nonetheless … Shabbat Shalom. In reading Parashat Bo this morning, I am intrigued by the absence of women and their role in the actual preparations to depart Egypt. This is particularly striking because women – Miriam, Moses’ mother Yocheved, the midwives Shifra and Puah, and Pharaoh’s daughter – are so dominant in the earlier part of the exodus story. In fact, the opening parashah of Exodus is replete with industrious, courageous women. Why no mention of them here? And how do we reconcile this difference? One of the ways in which moderns might interpret this is to focus on the context in which God commands Moses and the congregation of Hebrews – that is men – to perform certain tasks as they begin their journey out of Egypt. With great specificity God, through Moses, instructs the male heads of household how to prepare and eat the paschal sacrifice, place its blood on the doorpost, and remove all leaven from their homes. They are told how to ready themselves for a hasty departure. Why such detailed instruction? It is plausible that, like slaves before and after, the Hebrews had scant opportunity to cultivate imagination, creativity and independent thought during their enslavement. The opposite in fact is true, for any autonomous thought or deed is suppressed because the slave mentality is one of absolute submission to the will of his master. So this might account for why the Hebrew slaves required such specific instruction. The implication is that among the downtrodden, the impulse for freedom needs some prodding. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776 – 5778 2015 – 2018 Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 CONTENTS NOTES ....................................................................................................1 DATES OF FESTIVALS .............................................................................2 CALENDAR OF TORAH AND HAFTARAH READINGS 5776-5778 ............3 GLOSSARY ........................................................................................... 29 PERSONAL NOTES ............................................................................... 31 Published by: The Movement for Reform Judaism Sternberg Centre for Judaism 80 East End Road London N3 2SY [email protected] www.reformjudaism.org.uk Copyright © 2015 Movement for Reform Judaism (Version 2) Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5776-5778 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the MRJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. -

Old Testament Bible Class Curriculum

THE OLD TESTAMENT MOSES AND THE EXODUS Year 1 - Quarter 3 by F. L. Booth © 2005 F. L. Booth Zion, IL 60099 CONTENTS LESSON PAGE 1 The Birth of Moses 1 - 1 2 Moses Kills An Egyptian 2 - 1 3 Moses And The Burning Bush 3 - 1 4 Moses Meets Pharaoh 4 - 1 5 The Plagues 5 - 1 6 The Tenth Plague And The Passover 6 - 1 7 Crossing The Red Sea 7 - 1 8 Quails And Manna 8 - 1 9 Rephidim - Water From The Rock 9 - 1 10 The Ten Commandments 10 - 1 11 The Golden Calf 11 - 1 12 The Tabernacle 12 - 1 13 Nadab And Abihu 13 - 1 Map – The Exodus Plan of the Tabernacle 1 - 1 LESSON 1 THE BIRTH OF MOSES Ex. 1; 2:1-10 INTRODUCTION. After Jacob's family moved to Egypt, they increased and multiplied until the land was filled with them. Joseph died, many years passed, and a new king came to power who did not know Joseph. Afraid of the strength and might of the Israelites, the king began to afflict them, enslav- ing them and forcing them to build cities for him. He decreed that all boy babies born to the Hebrew women should be cast into the river. One Levite family hid their infant son. When they could no longer hide him, his mother put him in a basket and placed him in the river where the daughter of Pharaoh bathed. The royal princess found the basket and child, named him Moses which means to draw out, and raised him as her son. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Bo DeuteronomyExodus10:1-13:16 32:1 – 52 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Haazinu Study Guide Themes Parashat Bo Study Guide Themes Theme 1: Israel’s God Reigns Supreme Theme 1: Israel’s God Reigns Supreme Theme 2: The Obligation to Remember—Marking the Exodus in and after Egypt Theme 2: The Obligation to Remember—Marking the Exodus in and after Egypt Introduction arashat Bo contains the last three of the ten divine acts designed to persuade P a reluctant Pharaoh to release his Israelite slaves. Although these acts are most often referred to as “plagues,” the biblical text more commonly uses the words “signs” (otot), “marvels” (mof’tim), and “wonders” (nifla’ot) to describe these heavenly exhibitions of power. Pharaoh’s defiance of God’s command to let the people go brings terrible consequences for the Egyptian people. The preceding parashah (Va-eira) describes the first seven of these divine displays: the Nile turns to blood, frogs swarm over Egypt, dust turns to lice, swarms of insects invade the land, pestilence attacks Egypt’s animals, boils cover animals and humans, and hail destroys Egyptian livestock and fields. In this parashah God displays the final signs: locusts, darkness, and the slaying of the first-born. -

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles John A. Tvedtnes A portion of the brass plates brought by Lehi to the New World contained the books of Moses (1 Nephi 5:10-13). Nephi and other Book of Mormon writers stressed that they obeyed the laws given therein: “And we did observe to keep the judgments, and the statutes, and the commandments of the Lord in all things according to the law of Moses” (2 Nephi 5:10). But aside from sacrice2 and the Ten Commandments,3 we have few explicit details regarding the Nephite observance of the Mosaic code. One would expect, for example, some mention of the festivals which played such an important role in the religious observances of ancient Israel. Though the Book of Mormon mentions no religious festivals by name, it does detail many signicant Nephite assemblies. One of the more noteworthy of the Nephite ceremonies was the coronation of the second Mosiah by his father, Benjamin.4 Some years ago, Professor Hugh Nibley outlined the similarities between this Book of Mormon account and ancient Middle Eastern coronation rites.5 He pointed out that these rites took place at the annual New Year festival, when the people were placed under covenant of obedience to the monarch. My own research further explores the Israelite coronation/New Year rites, and aims to complement other scholarly studies of the ceremonial context of Benjamin’s speech. THE SABBATICAL FEASTS In the sacred calendar, the Israelite new year began with the month of Abib (later called Nisan), in the spring (end March/beginning April).6 This month encompassed the feasts of Passover (beginning at sundown on the fourteenth day) and Unleavened Bread (fourteenth through twenty-first days), and included “holy convocations,” analogous to the Latter-day Saint April general conference (Leviticus 23:4-8). -

AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH An-Exquisite-Medieval-Haggadah

ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 100 YEARS: AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/arts-culture/2019/04/on-view-for-the-first-time-in-100-years- an-exquisite-medieval-haggadah/ A few months ago, I was approached with a request to become involved in a then- secret mission: to examine one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands. April 23, 2019 | Marc Michael Epstein A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York —aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has A page from the Lombard Haggadah. Les issued a series of meticulously Enluminures. researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look? I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one. -

Walking with the Jewish Calendar

4607-ZIG-Walking with JEWISH CALENDAR [cover]_Cover 8/17/10 3:47 PM Page 1 The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Walking with the Jewish Calendar Edited By Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson ogb hfrsand vhfrsRachel Miriam Safman 4607-ZIG-WALKING WITH JEWISH CALENDAR-P_ZIG-Walking with 8/17/10 3:46 PM Page 43 SUKKOT, SHEMINI ATZERET, HOSHANA RABBAH, SIMCHAT TORAH RABBI JEFFREY L. RUBENSTEIN INTRODUCTION he festival of Sukkot (sometimes translated as “Booths” or “Tabernacles”) is one of the three pilgrimage festivals T(shalosh regalim). Celebrated for seven days, from the 15th to 21st of the Hebrew month of Tishrei, Sukkot is followed immediately by the festival of Shemini Atzeret (the “Eighth-day Assembly”), on the 22nd of Tishrei, thus creating an eight-day festival in all. In post-Talmudic times in the Diaspora, where the festivals were celebrated for an extra day, the second day of Shemini Atzeret, the 23rd of Tishrei, became known as “Simchat Torah” (“The Rejoicing for the Torah”) and developed a new festival identity. Like the other pilgrimage holidays, Pesach and Shavuot, Sukkot, includes both agricultural and historical dimensions, and the festival’s name can be explained with reference to either. The Torah connects the name “Sukkot” to the “booths” in which the Israelites dwelled throughout their desert sojourn: You shall live in sukkot seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in sukkot, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in sukkot when I brought them out of the land of Egypt; I am the Lord.1 As such the commandment to reside in booths links the festival to the historic exodus from Egypt and commemorates the experience of the Israelites as they wandered through the desert. -

Deuteronomy- Kings As Emerging Authoritative Books, a Conversation

DEUTERONOMY–KinGS as EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS A Conversation Edited by Diana V. Edelman Ancient Near East Monographs – Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) DEUTERONOMY–KINGS AS EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS Ancient Near East Monographs General Editors Ehud Ben Zvi Roxana Flammini Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach Esther J. Hamori Steven W. Holloway René Krüger Alan Lenzi Steven L. McKenzie Martti Nissinen Graciela Gestoso Singer Juan Manuel Tebes Number 6 DEUTERONOMY–KINGS AS EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS A CONVERSATION Edited by Diana V. Edelman Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta Copyright © 2014 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931428 Th e Ancient Near East Monographs/Monografi as Sobre El Antiguo Cercano Oriente series is published jointly by the Society of Biblical Literature and the Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación, Centro de Estu- dios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente. For further information, see: http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx http://www.uca.edu.ar/cehao Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence.