TUBI (Turkish Benthic Index): a New Biotic Index for Assessing Impacts of Organic Pollution on Benthic Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Programme 9Th FORUM on NEW MATERIALS

9th Forum on New Materials SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME 9th FORUM ON NEW MATERIALS FA-1:IL09 Clinical Significance of 3D Printing in Bone Disorder OPENING SESSION S. BOSE, School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Department of Chemistry, Elson Floyd College of Medicine, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA WELCOME ADDRESSES FA-1:IL10 Additive Manufacturing of Implantable Biomaterials: Processing Challenges, Biocompatibility Assessment and Clinical Translation Plenary Lectures B. BASU, Materials Research Centre & Center for BioSystems Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India F:PL1 Organic Actuators for Living Cell Opto Stimulation FA-1:IL11 Synthesis and Additive Manufacturing of Polycarbosilane G. LANZANI, Center for Nano Science and Technology@PoliMi, Istituto Systems Italiano di Tecnologia, and Department of Physics, Politecnico di Milano, K. MARtin1,2, L.A. Baldwin1, T.PatEL1,3, L.M. RUESCHHOFF1, C. Milano, Italy WYCKOFF1,4, J.J. BOWEN1,2, M. CINIBULK1, M.B. DICKERSON1, 1Materials F:PL2 New Materials and Approaches and Manufacturing Directorate, Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright- R.S. RUOFF, Ulsan National Institute of Science & Technology (UNIST), Patterson AFB, OH, USA; 2UES Inc., Dayton, OH, USA; 3NRC Research Ulsan, South Korea Associateship Programs, Washington DC, USA; 4Wright State University, Fairborn, OH, USA F:PL3 Brain-inspired Materials, Devices, and Circuits for Intelligent Systems FA-1:L12 Extending the Limits of Additive Manufacturing: Emerging YONG CHEN, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA Techniques to Process Metal-matrix Composites with Customized Properties A. SOLA, A. TRINCHI, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Australia, Manufacturing Business Unit, Metal Industries Program, Clayton, Australia SYMPOSIUM FA FA-1:L13 Patient Specific Stainless Steel 316 - Tricalcium Phosphate Biocomposite Cellular Structures for Tissue Applications Via Binder Jet Additive Manufacturing 3D PRINTING AND BEYOND: STATE- K. -

Chrysallida, Ondina (S.N

BASTERIA, 60: 45-56, 1996 Nordsieck’s Pyramidellidae (Gastropoda Prosobranchia): A revision of his types. Part 1: The genera Chrysallida, Ondina (s.n. Evalea) and Menestho J.J. van Aartsen Adm. Helfrichlaan 33, 6952 GB Dieren, The Netherlands & H.P.M.G. Menkhorst Natuurmuseum Rotterdam, P.O. Box 23452, 3001 KL Rotterdam, The Netherlands In the seventies F. Nordsieck introduced many new nominal taxa in the Pyramidellidae His material ofthe (Opisthobranchia). original genera Chrysallida, Ondina (s.n. Evalea) and Menestho has been revised. For some taxa lectotypes are designated. For Odostomia (Evalea) elegans A. is described. Adams, 1860, a neotype is designated. In addition Ondina jansseni sp. nov. Key words: Gastropoda,Opisthobranchia, Pyramidellidae, Chrysallida, Ondina, Evalea, Menestho, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION In the beginning of the seventies, many new nominal taxa of Atlantic and Mediter- ranean Pyramidellidae were published by F. Nordsieck. These taxa have been a source of difficulty ever since, because the descriptions were not always good enough for The if of Nordsieck's hand and had recognition. figures, published anyway, were own to more artistic than scientific value. It has therefore been a longstanding wish critically revise all these the basis of the material. taxa on type Thanks to the highly appreciated help ofDr. RonaldJanssen, curator of the Mollusca in the Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt, Germany, we were able to consult the collec- tion of F. Nordsieck, now in the collection of that museum. A ofall with has summary new taxa, references, already been published by R. Janssen (1988). From this list, containing the names of more than 400 alleged new species, varieties it becomes obvious that it is task for subspecies, or forms, an impossible any author to revise these all. -

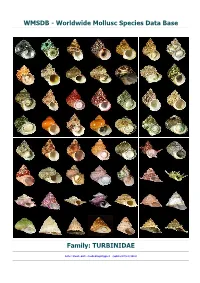

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Central Mediterranean Sea) Subtidal Cliff: a First, Tardy, Report

Biodiversity Journal , 2018, 9 (1): 25–34 Mollusc diversity in Capo d’Armi (Central Mediterranean Sea) subtidal cliff: a first, tardy, report Salvatore Giacobbe 1 & Walter Renda 2 ¹Department of Chemical, Biological, Pharmaceutical and Environmental Sciences, University of Messina, Viale F. Stagno d’Al - contres 31, 98166 Messina, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] 2Via Bologna, 18/A, 87032 Amantea, Cosenza, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT First quantitative data on mollusc assemblages from the Capo d’Armi cliff, at the south en - trance of the Strait of Messina, provided a baseline for monitoring changes in benthic biod- iversity of a crucial Mediterranean area, whose depletion might already be advanced. A total of 133 benthic taxa have been recorded, and their distribution evaluated according to depth and seasonality. Bathymetric distribution showed scanty differences between the 4-6 meters and 12-16 meters depth levels, sharing all the 22 most abundant species. Season markedly affected species composition, since 42 taxa were exclusively recorded in spring and 35 in autumn, contrary to 56 shared taxa. The occurrence of some uncommon taxa has also been discussed. The benthic mollusc assemblages, although sampled in Ionian Sea, showed a clear western species composition, in accordance with literature placing east of the Strait the bound- ary line between western and eastern Mediterranean eco-regions. Opposite, occasional records of six mesopelagic species, which included the first record for this area of Atlanta helicinoi - dea -

I. Türkiye Derin Deniz Ekosistemi Çaliştayi Bildiriler Kitabi 19 Haziran 2017

I. TÜRKİYE DERİN DENİZ EKOSİSTEMİ ÇALIŞTAYI BİLDİRİLER KİTABI 19 HAZİRAN 2017 İstanbul Üniversitesi, Su Bilimleri Fakültesi, Gökçeada Deniz Araştırmaları Birimi, Çanakkale, Gökçeada EDİTÖRLER ONUR GÖNÜLAL BAYRAM ÖZTÜRK NURİ BAŞUSTA Bu kitabın bütün hakları Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı’na aittir. İzinsiz basılamaz, çoğaltılamaz. Kitapta bulunan makalelerin bilimsel sorumluluğu yazarlarına aittir. All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission from the Turkish Marine Research Foundation. Copyright © Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı ISBN-978-975-8825-37-0 Kapak fotoğrafları: Mustafa YÜCEL, Bülent TOPALOĞLU, Onur GÖNÜLAL Kaynak Gösterme: GÖNÜLAL O., ÖZTÜRK B., BAŞUSTA N., (Ed.) 2017. I. Türkiye Derin Deniz Ekosistemi Çalıştayı Bildiriler Kitabı, Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı, İstanbul, Türkiye, TÜDAV Yayın no: 45 Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı (TÜDAV) P. K: 10, Beykoz / İstanbul, TÜRKİYE Tel: 0 216 424 07 72, Belgegeçer: 0 216 424 07 71 Eposta: [email protected] www.tudav.org ÖNSÖZ Dünya denizlerinde 200 metre derinlikten sonra başlayan bölgeler ‘Derin Deniz’ veya ‘Deep Sea’ olarak bilinir. Son 50 yılda sualtı teknolojisindeki gelişmelere bağlı olarak birçok ulus bu bilinmeyen deniz ortamlarını keşfetmek için yarışırken yeni cihazlar denemekte ayrıca yeni türler keşfetmektedirler. Özellikle Amerika, İngiltere, Kanada, Japonya başta olmak üzere birçok ülke derin denizlerin keşfi yanında derin deniz madenciliğine de ilgi göstermektedirler. Daha şimdiden Yeni Gine izin ve ruhsatlandırma işlemlerine başladı bile. Bütün bunlar olurken ülkemizde bu konuda çalışan uzmanları bir araya getirerek sinerji oluşturma görevini yine TÜDAV üstlendi. Memnuniyetle belirtmek gerekir ki bu çalıştay amacına ulaşmış 17 değişik kurumdan 30 uzman değişik konularda bildiriler sunarak konuya katkı sunmuşlardır. -

The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop Edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt

Achaemenid History • II The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Leiden 1987 ACHAEMENID HISTORY 11 THE GREEK SOURCES PROCEEDINGS OF THE GRONINGEN 1984 ACHAEMENID HISTORY WORKSHOP edited by HELEEN SANCISI-WEERDENBURG and AMELIE KUHRT NEDERLANDS INSTITUUT VOOR HET NABIJE OOSTEN LEIDEN 1987 © Copyright 1987 by Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Witte Singe! 24 Postbus 9515 2300 RA Leiden, Nederland All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Greek The Greek sources: proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid history workshop / ed. by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amelie Kuhrt. - Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.- (Achaemenid history; II) ISBN90-6258-402-0 SISO 922.6 UDC 935(063) NUHI 641 Trefw.: AchaemenidenjPerzische Rijk/Griekse oudheid; historiografie. ISBN 90 6258 402 0 Printed in Belgium TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations. VII-VIII Amelie Kuhrt and Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg INTRODUCTION. IX-XIII Pierre Briant INSTITUTIONS PERSES ET HISTOIRE COMPARATISTE DANS L'HIS- TORIOGRAPHIE GRECQUE. 1-10 P. Calmeyer GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY AND ACHAEMENID RELIEFS. 11-26 R.B. Stevenson LIES AND INVENTION IN DEINON'S PERSICA . 27-35 Alan Griffiths DEMOCEDES OF CROTON: A GREEKDOCTORATDARIUS' COURT. 37-51 CL Herrenschmidt NOTES SUR LA PARENTE CHEZ LES PERSES AU DEBUT DE L'EM- PIRE ACHEMENIDE. 53-67 Amelie Kuhrt and Susan Sherwin White XERXES' DESTRUCTION OF BABYLONIAN TEMPLES. 69-78 D.M. Lewis THE KING'S DINNER (Polyaenus IV 3.32). -

Nachruf Fritz Nordsieck (Aus Archiv Für Molluskenkunde 118)

Band 118 Nummer 4/6 Archiv für Molluskenkunde der Senckenber gischen Natur forschenden Gesellschaft Organ der Deutschen Malakozoologischen Gesellschaft Begründet von Prof. Dr. W. K obelt Weitergeführt von Dr.W. W enz, Dr. F. H aas und Dr. A. Zilch Herausgegeben von Dr. R. J anssen Arch. Moll. | 118 (1987) | (4/6) 1 105-128 | Frankfurt am Main, 01. 07. 1988 Fritz Nordsieck (1906-1984) 105 Am 23.5.1984 verstarb im Alter von 78 Jahren Dr.F ritz N ordsieck, der mit seinen Büchern über die europäischen Meeresmollusken weit über Deutschland hinaus bekannt geworden war. F ritz N ordsieck wurde am 8.3.1906 als drittes von vier Kindern eines kaufmänni schen Angestellten in Düsseldorf geboren. Trotz widriger Umstände — sein Vater war Kriegsinvalide geworden, die Mutter frühzeitig gestorben — nahmF ritz N ordsieck nach dem Abitur das Studium der Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften auf. Sein Studium an der Universität Köln von 1925—1930 mußte er sich durch Eigenarbeit und Darlehen selbst finanzieren. Nach der Promotion war er an der Universität Köln zunächst als wissen schaftlicher Assistent in den Fächern Betriebswirtschaft und Betriebsorganisation tätig, bevor er ab 1934 wissenschaftlicher Referent am Deutschen Gemeindetag in Berlin wurde. In dieser Zeit fungierteN ordsieck auch als Hauptschriftleiter der Zeitschrift für öffentli che Wirtschaft. Eine Habilitation scheiterte 1936 aus politischen Gründen. Während der Zeit in Berlin verfaßte N ordsieck etliche Bücher über Betriebsorganisation, Organisa tionslehre und kommunale Verwaltung, die in mehreren Auflagen erschienen. 1934 heirateteF ritz N ordsieck nach gemeinsamem Studium und Assistententätigkeit seine Frau H ildegard. Es wurden ihnen fünf Kinder geboren, von denen sich sein Sohn H artmut ebenfalls der Malakologie zugewandt hat. -

The Kerkenes Project

THE KERKENES PROJECT PRELIMINARY REPORT FOR THE 2001 SEASON Figure 1: Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg experiments with electromagnetic induction in the city that was first mapped by his great uncle Hans Henning von der Osten and H. F. Blackburn. Geoffrey Summers, Françoise Summers and David Stronach http://www.metu.edu.tr/home/wwwkerk/ THE KERKENES PROJECT Faculty of Architecture, Room 417 – New Architecture Building, Middle East Technical University, 06531 Ankara, TURKEY Tel: +90 312 210 6216 Fax: +90 312 210 1249 or British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Tahran Caddesi 24, Kavaklıdere, 06700 Ankara, TURKEY Tel: +90 312 427 5487 Fax: +90 312 428 0159 Dr. Geoffrey Summers Dept. of Political Science and Public Administration, Middle East Technical University. Tel/Fax: +90 312 210 1485 e-mail: [email protected] Mrs. Françoise Summers Dept. of Architecture, Middle East Technical University. e-mail: [email protected] Prof. David Stronach Dept. of Near Eastern Studies, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94750-1940, USA. Tel: +1 510 642 7794 Fax: +1 510 643 8430 2 Figure 2: The team with the city behind. ABSTRACT The 2001 field season at the Iron Age city on the Kerkenes Dağ concentrated on geophysical survey within the lower part of the burnt city. Geomagnetic survey was conducted over a very considerable portion of the lower city area. At the same time, experimentation with resistivity and electromagnetic induction techniques produced new insights in carefully selected areas. Highlights include the discovery of what appear to be megarons, the first such buildings to have been recognised at Kerkenes. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Malacofauna from Soft Bottoms in the Cerro Gordo Marine Cave (Alboran Sea): Biodiversity and Spatial Distribution

Research Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.22920 Malacofauna from soft bottoms in the Cerro Gordo marine cave (Alboran Sea): biodiversity and spatial distribution Lidia PINO1, Carlos NAVARRO-BARRANCO2 and Serge GOFAS1 1 Department of Animal Biology, University of Malaga, Teatinos Campus, 29071, Malaga, Spain 2 Department of Zoology, University of Seville, Avda. Reina Mercedes 6, 41012, Seville, Spain Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Vasilis GEROVASILEIOU Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 10 August 2020; Published online: 20 November 2020 Abstract A study has been carried out for the first time of the molluscan fauna of the Cerro Gordo submarine cave in the Spanish part of the Alboran Sea. The depth of the cave bottom ranges from 16 m at its entrance, to sea level at its innermost section. Replicate soft-bottom samples were collected from three different stations along the horizontal gradient of the cave. Additional samples were collected on photophilous hard bottoms next to the cave entrance in order to assess the origin of cave bioclasts. The cave sediments contained 158 species of molluscs (23 collected alive and 155 recorded as shells), more than in Mediterranean cave sediments else- where. Species richness and abundance of molluscs decreased from the outermost to the innermost part of the cave. No cave-ex- clusive species were found, possibly due to the scarcity of caves in the Alboran Sea, but many of the recorded species are known from other Mediterranean caves. -

Erken Lydia Dönemi Tarihi Ve Arkeolojisi

T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ ARKEOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI 2019-YL–196 ERKEN LYDIA DÖNEMİ TARİHİ VE ARKEOLOJİSİ HAZIRLAYAN Murat AKTAŞ TEZ DANIŞMANI Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ AYDIN- 2019 T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE AYDIN Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Programı öğrencisi Murat AKTAŞ tarafından hazırlanan Erken Lydia Dönemi Tarihi ve Arkeolojisi başlıklı tez, …….2019 tarihinde yapılan savunma sonucunda aşağıda isimleri bulunan jüri üyelerince kabul edilmiştir. Unvanı, Adı ve Soyadı : Kurumu : İmzası : Başkan : Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ ADÜ ………… Üye : Doç. Dr. Ali OZAN PAÜ ………… Üye : Dr. Öğr. Üyesi. Aydın ERÖN ADÜ ………… Jüri üyeleri tarafından kabul edilen bu Yüksek Lisans tezi, Enstitü Yönetim Kurulunun …………..tarih………..sayılı kararı ile onaylanmıştır. Doç. Dr. Ahmet Can BAKKALCI Enstitü Müdürü V. iii T.C. AYDIN ADNAN MENDERES ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE AYDIN Bu tezde sunulan tüm bilgi ve sonuçların, bilimsel yöntemlerle yürütülen gerçek deney ve gözlemler çerçevesinde tarafımdan elde edildiğini, çalışmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düşünce, sonuç ve bilgilere bilimsel etik kurallarının gereği olarak eksiksiz şekilde uygun atıf yaptığımı ve kaynak göstererek belirttiğimi beyan ederim. …../…../2019 Murat AKTAŞ iv ÖZET ERKEN LYDIA DÖNEMİ TARİHİ VE ARKEOLOJİSİ Murat AKTAŞ Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Engin AKDENİZ 2019, XVI + 157 sayfa Batı Anadolu’da Hermos (Gediz) ve Kaystros (Küçük Menderes) ırmaklarının vadilerini kapsayan coğrafyaya yerleşen Lydialılar'ın nereden ve ne zaman geldikleri kesin olarak bilinmemektedir. Ancak Lydialılar'ın MÖ II. bin yılın ikinci yarısından itibaren Anadolu’da var oldukları anlaşılmaktadır. Herodotos, Troia savaşından itibaren Herakles oğullarının bölgede beş yüz yıl hüküm sürdüğünden bahseder. -

Marine Molluscs in a Changing Environment”

PHYSIO MAR Physiomar 08 Physiological aspects of reproduction, nutrition and growth “Marine molluscs in a changing environment” IUEM CNRS IRD Book of abstracts INSTITUT UNIVERSITAIRE EUROPEEN DE LA MER http://www.univ-brest.fr/IUEM/PHYSIOMAR/ UNIVERSITE DE BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE Ifremer Physiomar 08 – Brest, France – 1-4 September, 2008 PHYSIOMAR 08 "Marine molluscs in a changing environment" 2nd marine mollusc physiology conference Brest, France, September 1-4, 2008 Compiled by : M. Gaasbeek and H. McCombie Editor : Ifremer 1 Physiomar 08 – Brest, France – 1-4 September, 2008 2 Physiomar 08 – Brest, France – 1-4 September, 2008 Welcome to Physiomar 2008 Welcome to the Physiomar 2008 conference and to Brest! This second mollusc physiology meeting is being organized jointly by LEMAR (IUEM: European Institute for Marine Studies) and LPI (Ifremer: French Institute for the Exploitation of the Sea), as both laboratories conduct research in this field. Physiomar 08 follows the very successful workshop ‘Physiological aspects of reproduction and nutrition in marine mollusks’ held in La Paz (Mexico) in November 2006 under the guidance of Maria Concepcion Lora Vilchis and Elena Palacios Metchenov from CIBNOR. This year’s meeting will focus on Reproduction, Growth, Nutrition and Genetics and genomics of marine molluscs, and include a specific session on the effects of climate change on mollusc physiology: Global change. This conference will serve as a forum for the communication of recent advances in all aspects of the physiology in molluscs. Researchers, students, stakeholders and mollusc farmers will have the opportunity to communicate personally in a friendly environment with leaders in the field. This meeting aims to provide a vehicle for continuing exchanges, cooperation, and collaboration in the field of the physiology of marine molluscs to better understand their adaptation ability in a changing environment, their ecological significance, and to promote their sustainable culture.