The NIOSH Occupational Exposure Banding Process for Chemical Risk Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detectable Compounds by MIP.Pdf

Boiling Molecular Density Ionization Solubility Vapor Analytes Point Weight Potential in Water Pressure ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐Detected By‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Wiki Website Chemical Compound: (oC) (g/mol) (g/mL) (eV) g/L kPa PID* FID** XSD ECD*** @ ~25C 10.6 eV https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methane . Methane ‐161 16.0 .657 g/L 12.61 0.02 n y n n https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dichlorodifluoromethane . Freon 12 (Dichlorodifluoromethane) ‐29.8 120.9 1.486 12.31 0.3 568.0 n y y LS**** https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1,1,2‐Trichloro‐1,2,2‐trifluoroethane . Freon 113 (1,1,2‐Trichloro‐1,2,2‐trifluoroethane) 47.7 187.4 1.564 11.78 0.17 285mm Hg n y y y https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinyl_chloride . Vinyl Chloride (Chloroethene) ‐13.0 62.5 0.910 10.00 2.7 2580mm Hg y y y LS https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bromomethane . Bromomethane 3.6 94.9 3.974 10.53 17.5 190.0 n y y LS https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chloroethane .. Chloroethane 12.3 64.5 0.901 10.97 5.74 134.6 n y y LS https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trichlorofluoromethane . Freon 11 (Trichlorofluoromethane) 23.8 137.4 1.494 11.77 1.1 89.0 n y y y https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acetone . Acetone 56.5 58.1 0.790 9.69 Miscible 30.6 y y n n https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1,1‐Dichloroethene . 1,1‐Dichloroethene 32.0 97.0 1.213 9.65 0.04% y y y LS https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dichloromethane . -

Release of Melamine and Formaldehyde from Melamine-Formaldehyde Plastic Kitchenware

molecules Article Release of Melamine and Formaldehyde from Melamine-Formaldehyde Plastic Kitchenware , Ingo Ebner * y , Steffi Haberer, Stefan Sander, Oliver Kappenstein , Andreas Luch and Torsten Bruhn y Department of Chemical and Product Safety, German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Max-Dohrn-Str. 8-10, 10589 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (O.K.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (T.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-18412-27403 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Academic Editor: Roland Franz Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 31 July 2020; Published: 10 August 2020 Abstract: The release of melamine and formaldehyde from kitchenware made of melamine resins is still a matter of great concern. To investigate the migration and release behavior of the monomers from melamine-based food contact materials into food simulants and food stuffs, cooking spoons were tested under so-called hot plate conditions at 100 ◦C. Release conditions using the real hot plate conditions with 3% acetic acid were compared with conditions in a conventional migration oven and with a release to deionized water. Furthermore, the kinetics of the release were studied using Arrhenius plots giving an activation energy for the release of melamine of 120 kJ/mol. Finally, a correlation between quality of the resins, specifically the kind of bridges between the monomers, and the release of melamine, was confirmed by CP/MAS 13C-NMR measurements of the melamine kitchenware. Obviously, the ratio of methylene bridges and dimethylene ether bridges connecting the melamine monomers during the curing process can be directly correlated with the amount of the monomers released into food. -

The Use and Storage of Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) at Bayer Cropscience

Summary The Use and Storage of Methyl Isocyanate (MIC) at Bayer CropScience The use of hazardous chemicals such as methyl isocyanate can be a significant concern to the residents of communities adjacent to chemical facilities, but is often an integral, necessary part of the chemical manufacturing process. In order to ensure that chemical manufacturing takes place in a manner that is safe for workers, members of the local community, and the environment, the philosophy of inherently safer processing can be used to identify opportuni ties to eliminate or reduce the hazards associated with chemical processing. However, the concepts of inherently safer process analysis have not yet been adopted in all chemical manu facturing plants. This report presents a possible framework to help plant managers choose between alternative processing options—considering factors such as environmental impact and product yield as well as safety—to develop a chemical manufacturing system. n 2008, an explosion at the Bayer CropScience chemical production Iplant in Institute, West Virginia, resulted in the deaths of two employees, a fire within the production unit, and extensive damage to nearby structures. The accident drew renewed attention to the fact that the Bayer facility manufac tured and stored methyl isocyanate, or MIC—a volatile, highly toxic chemical used in the production of carbamate pesticides and the agent responsible for thousands of deaths in Bhopal, India, in 1984. In the Institute incident, debris Figure 1. The Bayer CropScience facility at Insitute, WV. from the blast hit the shield surrounding Google Earth satellite image: © 2012 Google a MIC storage tank, and although the container was not damaged, an investiga tion by the U.S. -

Exposure Investigation Protocol: the Identification of Air Contaminants Around the Continental Aluminum Plant in New Hudson, Michigan Conducted by ATSDR and MDCH

Exposure Investigation Protocol - Continental Aluminum New Hudson, Lyon Township, Oakland County, Michigan Exposure Investigation Protocol: The Identification of Air Contaminants Around the Continental Aluminum Plant in New Hudson, Michigan Conducted by ATSDR and MDCH MDCH/ATSDR - 2004 Exposure Investigation Protocol - Continental Aluminum New Hudson, Lyon Township, Oakland County, Michigan TABLE OF CONTENTS OBJECTIVE/PURPOSE..................................................................................................... 3 RATIONALE...................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 5 AGENCY ROLES .............................................................................................................. 6 ESTABLISHING CRITERIA ............................................................................................ 7 “Odor Events”................................................................................................................. 7 Comparison Values......................................................................................................... 7 METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 12 Instantaneous (“Grab”) Air Sampling........................................................................... 12 Continuous Air Monitoring.......................................................................................... -

Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders Author(s): Chad Huffman, Ph.D., Lars Ericson, Ph.D. Document No.: 246708 Date Received: May 2014 Award Number: 2010-IJ-CX-K024 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Assessment of Portable HAZMAT Sensors for First Responders DOJ Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Sensor, Surveillance, and Biometric Technologies (SSBT) Center of Excellence (CoE) March 1, 2012 Submitted by ManTech Advanced Systems International 1000 Technology Drive, Suite 3310 Fairmont, West Virginia 26554 Telephone: (304) 368-4120 Fax: (304) 366-8096 Dr. Chad Huffman, Senior Scientist Dr. Lars Ericson, Director UNCLASSIFIED This project was supported by Award No. 2010-IJ-CX-K024, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality : Selected Pollutants

WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: This book presents WHO guidelines for the protection of pub- lic health from risks due to a number of chemicals commonly present in indoor air. The substances considered in this review, i.e. benzene, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, naphthalene, nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (especially benzo[a]pyrene), radon, trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethyl- ene, have indoor sources, are known in respect of their hazard- ousness to health and are often found indoors in concentrations of health concern. The guidelines are targeted at public health professionals involved in preventing health risks of environmen- SELECTED CHEMICALS SELECTED tal exposures, as well as specialists and authorities involved in the design and use of buildings, indoor materials and products. POLLUTANTS They provide a scientific basis for legally enforceable standards. World Health Organization Regional Offi ce for Europe Scherfi gsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Tel.: +45 39 17 17 17. Fax: +45 39 17 18 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.euro.who.int WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health, Bonn Office, WHO Regional Office for Europe coordinated the development of these WHO guidelines. Keywords AIR POLLUTION, INDOOR - prevention and control AIR POLLUTANTS - adverse effects ORGANIC CHEMICALS ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE - adverse effects GUIDELINES ISBN 978 92 890 0213 4 Address requests for publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for per- mission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Catalyzed Reaction of Isocyanates (RNCO) with Water

Catalyzed Reaction of Isocyanates (RNCO) with Water Mark E. Wolf,y Jonathon E. Vandezande,z,{ and Henry F. Schaefer III∗,y yCenter for Computational Quantum Chemistry, University of Georgia, 140 Cedar Street, Athens, Georgia 30602, USA z1st Source Research, 617 Hutton St., Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, USA {Zymergen, 5980 Horton Street, Suite 105, Emeryville, California 94608, USA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +1 706 542-2067. Fax: +1 706 542-0406 Abstract The reactions between substituted isocyanates (RNCO) and other small molecules (e.g. water, alcohols, and amines) are of significant industrial importance, particularly for the development of novel polyurethanes and other useful polymers. We present very high level ab initio computations on the HNCO + H2O reaction, with results tar- geting the CCSDT(Q)/CBS//CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ level of theory. Our results affirm that hydrolysis can occur across both the N−C and C−O bonds of HNCO via con- certed mechanisms to form carbamate or imidic acid with ∆H0K barrier heights of 38.5 −1 and 47.5 kcal mol . A total of 24 substituted RNCO + H2O reactions were studied. Geometries obtained with a composite method and refined with CCSD(T)/CBS single point energies determine that substituted RNCO species have a significant influence on these barrier heights, with an extreme case like fluorine lowering both barriers by close to 20 kcal mol−1 and most common alkyl substituents lowering both by approxi- mately 4 kcal mol−1. Natural Bond Oribtal (NBO) analysis provides evidence that the 1 predicted barrier heights are strongly associated with the occupation of the in-plane C−O* orbital of the RNCO reactant. -

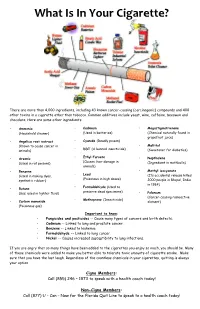

What Is in Your Cigarette?

What Is In Your Cigarette? There are more than 4,000 ingredients, including 43 known cancer-causing (carcinogenic) compounds and 400 other toxins in a cigarette other than tobacco. Common additives include yeast, wine, caffeine, beeswax and chocolate. Here are some other ingredients: • Ammonia • Cadmium • Megastigmatrienone (Household cleaner) (Used in batteries) (Chemical naturally found in grapefruit juice) • Angelica root extract • Cyanide (Deadly poison) (Known to cause cancer in • Maltitol • DDT (A banned insecticide) animals) (Sweetener for diabetics) • Ethyl Furoate • Arsenic • Napthalene (Causes liver damage in (Used in rat poisons) (Ingredient in mothballs) animals) • Benzene • Methyl isocyanate • Lead (Used in making dyes, (Its accidental release killed (Poisonous in high doses) synthetic rubber) 2000 people in Bhopal, India in 1984) • Formaldehiyde (Used to • Butane preserve dead specimens) (Gas; used in lighter fluid) • Polonium (Cancer-causing radioactive • Methoprene (Insecticide) • Carbon monoxide element) (Poisonous gas) Important to know: • Fungicides and pesticides -- Cause many types of cancers and birth defects. • Cadmium -- Linked to lung and prostate cancer. • Benzene -- Linked to leukemia. • Formaldehyde -- Linked to lung cancer. • Nickel -- Causes increased susceptibility to lung infections. If you are angry that so many things have been added to the cigarettes you enjoy so much, you should be. Many of these chemicals were added to make you better able to tolerate toxic amounts of cigarette smoke. Make sure that you have the last laugh. Regardless of the countless chemicals in your cigarettes, quitting is always your option. Cigna Members: Call (855) 246 – 1873 to speak with a health coach today! Non-Cigna Members: Call (877) U – Can – Now for the Florida Quit Line to speak to a health coach today! . -

Product Stewardship Summary Carbon Tetrachloride

Product Stewardship Summary Carbon Tetrachloride May 31, 2017 version Summary This Product Stewardship Summary is intended to give general information about Carbon Tetrachloride. It is not intended to provide an in-depth discussion of all health and safety information about the product or to replace any required regulatory communications. Carbon tetrachloride is a colorless liquid with a sweet smell that can be detected at low levels; however, odor is not a reliable indicator that occupational exposure levels have not been exceeded. Its chemical formula is CC14. Most emissive uses of carbon tetrachloride, a “Class I” ozone-depleting substance (ODS), have been phased out under the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol). Certain industrial uses (e.g. feedstock/intermediate, essential laboratory and analytical procedures, and process agent) are allowed under the Montreal Protocol. 1. Chemical Identity Name: carbon tetrachloride Synonyms: tetrachloromethane, methane tetrachloride, perchloromethane, benzinoform Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) number: 56-23-5 Chemical Formula: CC14 Molecular Weight: 153.8 Carbon tetrachloride is a colorless liquid. It has a sweet odor, and is practically nonflammable at ambient temperatures. 2. Production Carbon tetrachloride can be manufactured by the chlorination of methyl chloride according to the following reaction: CH3C1+ 3C12 —> CC14 + 3HC1 Carbon tetrachloride can also be formed as a byproduct of the manufacture of chloromethanes or perchloroethylene. OxyChem manufactures carbon tetrachloride at facilities in Geismar, Louisiana and Wichita, Kansas. Page 1 of 7 3. Uses The use of carbon tetrachloride in consumer products is banned by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), under the Federal Hazardous Substance Act (FHSA) 16 CFR 1500.17. -

Annexure Iii

ANNEXURE III DETAILS OF PRODUCTION AND MANUFACTURING PROCESS 1. RSF Intermediate Manufacturing process: Check and prepare a clean and dry vessel. Remove oxygen from the vessel with nitrogen flushing. Charge the required quantity of Formaldehyde into the clean vessel, followed by Urea and Glyoxal 40% and diethylene glycol. The temperature is increased to 60-80 C under constant stirring. The process is continued for 5-6 hours. Take sample for quality check and if required specifications are not meet, continue reaction further for 1 hour and again check for quality. If specification is reached fill product in containers, to be used for further formulations of finished product. Chemical Reaction Material Balance Input Output Formaldehyde 0.40 RSF Urea 0.20 Reaction Vessel 1.00 Intermediate Glyoxal 0.40 Total 1.00 Total 1.00 Process Flow Diagram M/S. Dystar India Pvt. Ltd., Plot No. 3002/A,GIDC Ankleshwar, Bharuch (GJ) 2. NFF-T Intermediate Manufacturing process: Check and prepare a clean and dry vessel. Remove oxygen from the vessel with nitrogen flushing. Charge the required quantity of glyoxal 40%and water into the clean vessel under constant stirring. Cool the vessel and add N, N-dimethyl urea until homogenous mixture is achieved. The temperature is maintained below ambient temperature and reaction is further continued for 2-4 hours under catalytic concentration of citric acid. Take sample for quality check and if required specifications are not meet, continue reaction further for 1 hour and again check for quality. If specification is reached fill product in containers, to be used for further formulations of finished product. -

1. Detta Föreställer Kapitelrubrik (1K Kapitelrubrik)

SCOEL/SUM/118 September 2006 Recommendation from the Scientific Committee on Occupational Exposure Limits for Methyl Isocyanate 8-hour TWA: - STEL (15 min): 0,02 ppm Additional classification: - Substance Identity and Properties CAS No.: 624-83-9 Synonyms: isocyanic acid methylester Structure: H3C-N=C=O Molecular weight: 57.06 Boiling point: 39°C Melting point: -45°C Vapour pressure: 46.4 kPa (20°C) Conversion factors: 1 ppm = 2.4 mg/m3 1 mg/m3 = 0.4 ppm Classification: F+; R12 Extremely flammable Repr.Cat.3; R63 Possible risk of harm to the unborn child T+; R26 Very toxic by inhalation T; R24/25 Toxic in contact with skin and if swallowed R42/43 May cause sensitization by inhalation and skin contact Xi; R37/38 Irritating to respiratory system and skin R41 Risk of serious damage to eyes 1 This summary document is based on a consensus document from the Swedish Criteria Group for Occupational Standards (Montelius, 2002). Methyl isocyanate (MIC) is a monoisocyanate and should be distinguished from the diisocyanates. At room temperature MIC is a clear liquid. It is sparingly soluble in water, although on contact with water it reacts violently, producing a large amount of heat. MIC has a sharp odour with an odour threshold above 2 ppm (Römpp and Falbe, 1997). Occurrence and Use Methylisocyanate (MIC) occurs primarily as an intermediate in the production of carbamate pesticides. It has also been used in the production of polymers (Hrhyhorczuk et al., 1992). Photolytic breakdown of N-methyldithiocarbamate releases some MIC, and it can therefore occur in the air around application of the pesticides (Geddes et al., 1995). -

Production and Characterization of Melamine-Formaldehyde Moulding

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Sciences, Technology and Engineering | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 6, Issue 2 (February 2020) PRODUCTION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF MELAMINE- FORMALDEHYDE MOULDING POWDER BY BALOGUN, Ayodeji Timothy REG. NO.: 98/6907EH Department of Chemical Engineering, School of Engineering and Engineering Technology, Federal University of Technology Minna, Nigeria. 26 International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Sciences, Technology and Engineering | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 6, Issue 2 (February 2020) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Amino resins are product of polymeric reaction of amino compound with aldehyde especially formaldehyde by a series of addition and condensation reaction. The reaction between formaldehyde and amino compound to form methyl derivatives of the later which on heating condenses to form hard, colourless transparent resin, when cured or heat set, the amino resins are more properly called amino plastics. 1.1 Background to the Study Melamine, the amino group in the production of melamine-formaldehyde is manufactured from coal, limestone and air, we do not indeed use coal as an ingredient but coke, its derivatives. It is obtained together with coal gas and coal tar when bituminous coal is heated in a by-product oven. Lime, another important reactant in the production of melamine is obtained by heating limestone in a kiln to liberate carbon dioxide with nitrogen to form calcium cyan amide which on further reaction with water and acid forms cynamide from which dicyandiamide is obtained by treatment with alkaline. Finally, dicyandiamide is heated with ammonia and methanol to produced melamine. Production of formaldehyde involves the reaction of coke with superheated steam to form hydrogen and carbon monoxide when these two gases are heated under high pressure in the presence of chromic oxide and zinc oxide or some other catalyst, methanol is formed.