Osteoclast Multinucleation: Review of Current Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

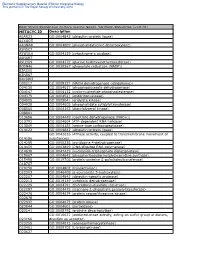

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Ncf1 Affects Osteoclast Formation but Is Not Critical for Postmenopausal

Stubelius et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2016) 17:464 DOI 10.1186/s12891-016-1315-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Ncf1 affects osteoclast formation but is not critical for postmenopausal bone loss Alexandra Stubelius1*, Annica Andersson1, Rikard Holmdahl3, Claes Ohlsson2, Ulrika Islander1 and Hans Carlsten1 Abstract Background: Increased reactive oxygen species and estrogen deficiency contribute to the pathophysiology of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Reactive oxygen species contribute to bone degradation and is necessary for RANKL- induced osteoclast differentiation. In postmenopausal bone loss, reactive oxygen species can also activate immune cells to further enhance bone resorption. Here, we investigated the role of reactive oxygen species in ovariectomy- induced osteoporosis in mice deficient in Ncf1, a subunit for the NADPH oxidase 2 and a well-known regulator of the immune system. Methods: B10.Q wild-type (WT) mice and mice with a spontaneous point mutation in the Ncf1-gene (Ncf1*/*) were ovariectomized (ovx) or sham-operated. After 4 weeks, osteoclasts were generated ex vivo, and bone mineral density was measured using peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Lymphocyte populations, macrophages, pre-osteoclasts and intracellular reactive oxygen species were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results: After ovx, Ncf1*/*-mice formed fewer osteoclasts ex vivo compared to WT mice. However, trabecular bone mineral density decreased similarly in both genotypes after ovx. Ncf1*/*-mice had a larger population of pre- osteoclasts, whereas lymphocytes were activated to the same extent in both genotypes. Conclusion: Ncf1*/*-mice develop fewer osteoclasts after ovx than WT mice. However, irrespective of genotype, bone mineral density decreases after ovx, indicating that a compensatory mechanism retains bone degradation after ovx. -

Formation of Osteoclast-Like Cells from Peripheral Blood of Periodontitis Patients Occurs Without Supplementation of Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 568–575 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01241.x Stanley T. S. Tjoa1, Teun J. de Formation of osteoclast-like cells Vries1,2, Ton Schoenmaker1,2, Angele Kelder3, Bruno G. Loos1 and Vincent Everts2 from peripheral blood of 1Department of Periodontology, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), Universiteit van Amsterdam and Vrije periodontitis patients occurs Universteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Oral Cell Biology, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), without supplementation of Universiteit van Amsterdam and Vrije Universteit, Amsterdam, Research Institute MOVE, The Netherlands; 3Department of Hematology, VUMC, Vrije Universiteit, macrophage colony-stimulating Amsterdam, The Netherlands factor Tjoa STS, de Vries TJ, Schoenmaker T, Kelder A, Loos BG, Everts V. Formation of osteoclast-like cells from peripheral blood of periodontitis patients occurs without supplementation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 568–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01241.x. Abstract Aim: To determine whether peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from chronic periodontitis patients differ from PBMCs from matched control patients in their capacity to form osteoclast-like cells. Material and Methods: PBMCs from 10 subjects with severe chronic periodontitis and their matched controls were cultured on plastic or on bone slices without or with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL). The number of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRACP1) multinucleated cells (MNCs) and bone resorption were assessed. Results: TRACP1 MNCs were formed under all culture conditions, in patient and control cultures. In periodontitis patients, the formation of TRACP1 MNC was similar for all three culture conditions; thus supplementation of the cytokines was not needed to induce MNC formation. -

Elephantid Genomes Reveal the Molecular Bases of Woolly Mammoth Adaptations to the Arctic

Article Elephantid Genomes Reveal the Molecular Bases of Woolly Mammoth Adaptations to the Arctic Graphical Abstract Authors Vincent J. Lynch, Oscar C. Bedoya-Reina, Aakrosh Ratan, ..., George H. Perry, Webb Miller, Stephan C. Schuster Correspondence [email protected] (V.J.L.), [email protected] (W.M.) In Brief Lynch et al. sequence complete genomes from three Asian elephants and two woolly mammoths and identify amino acid changes unique to woolly mammoths. Woolly-mammoth-specific amino acid changes underlie cold- adapted traits in mammoths, including small ears, thick fur, and altered temperature sensation. Highlights d Complete genomes of three Asian elephants and two woolly mammoths were sequenced d Mammoth-specific amino acid changes were found in 1,642 protein-coding genes d Genes with mammoth-specific changes are associated with adaptation to extreme cold d An amino acid change in TRPV3 may have altered temperature sensation in mammoths Lynch et al., 2015, Cell Reports 12, 217–228 July 14, 2015 ª2015 The Authors http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.027 Cell Reports Article Elephantid Genomes Reveal the Molecular Bases of Woolly Mammoth Adaptations to the Arctic Vincent J. Lynch,1,* Oscar C. Bedoya-Reina,2,4 Aakrosh Ratan,2,5 Michael Sulak,1 Daniela I. Drautz-Moses,2,6 George H. Perry,3 Webb Miller,2,* and Stephan C. Schuster2,6 1Department of Human Genetics, The University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, CLSC 319C, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 2Center for Comparative Genomics and Bioinformatics, Pennsylvania State University, 506B -

PROTEOMIC ANALYSIS of HUMAN URINARY EXOSOMES. Patricia

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PROTEOMIC ANALYSIS OF HUMAN URINARY EXOSOMES. Patricia Amalia Gonzales Mancilla, Ph.D., 2009 Directed By: Associate Professor Nam Sun Wang, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Exosomes originate as the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) in cells. These small vesicles (40-100 nm) have been shown to be secreted by most cell types throughout the body. In the kidney, urinary exosomes are released to the urine by fusion of the outer membrane of the MVBs with the apical plasma membrane of renal tubular epithelia. Exosomes contain apical membrane and cytosolic proteins and can be isolated using differential centrifugation. The analysis of urinary exosomes provides a non- invasive means of acquiring information about the physiological or pathophysiological state of renal cells. The overall objective of this research was to develop methods and knowledge infrastructure for urinary proteomics. We proposed to conduct a proteomic analysis of human urinary exosomes. The first objective was to profile the proteome of human urinary exosomes using liquid chromatography-tandem spectrometry (LC- MS/MS) and specialized software for identification of peptide sequences from fragmentation spectra. We unambiguously identified 1132 proteins. In addition, the phosphoproteome of human urinary exosomes was profiled using the neutral loss scanning acquisition mode of LC-MS/MS. The phosphoproteomic profiling identified 19 phosphorylation sites corresponding to 14 phosphoproteins. The second objective was to analyze urinary exosomes samples isolated from patients with genetic mutations. Polyclonal antibodies were generated to recognize epitopes on the gene products of these genetic mutations, NKCC2 and MRP4. The potential usefulness of urinary exosome analysis was demonstrated using the well-defined renal tubulopathy, Bartter syndrome type I and using the single nucleotide polymorphism in the ABCC4 gene. -

Zebrafish Mutants Calamity and Catastrophe Define Critical Pathways of Gene–Nutrient Interactions in Developmental Copper Metabolism Erik C

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2008 Zebrafish mutants calamity and catastrophe define critical pathways of gene–nutrient interactions in developmental copper metabolism Erik C. Madsen Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Jonathan D. Gitlin Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Madsen, Erik C. and Gitlin, Jonathan D., ,"Zebrafish mutants calamity and catastrophe define critical pathways of gene–nutrient interactions in developmental copper metabolism." PLoS Genetics.,. e1000261. (2008). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/892 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zebrafish Mutants calamity and catastrophe Define Critical Pathways of Gene–Nutrient Interactions in Developmental Copper Metabolism Erik C. Madsen, Jonathan D. Gitlin¤* Edward Mallinckrodt Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America Abstract Nutrient availability is an important environmental variable during development that has significant effects on the metabolism, health, and viability of an organism. To understand these interactions for the nutrient copper, we used a chemical genetic screen for zebrafish mutants sensitive to developmental copper deficiency. In this screen, we isolated two mutants that define subtleties of copper metabolism. The first contains a viable hypomorphic allele of atp7a and results in a loss of pigmentation when exposed to mild nutritional copper deficiency. -

2020 Program Book

PROGRAM BOOK Note that TAGC was cancelled and held online with a different schedule and program. This document serves as a record of the original program designed for the in-person meeting. April 22–26, 2020 Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center Metro Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS About the GSA ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Conference Organizers ...........................................................................................................................................4 General Information ...............................................................................................................................................7 Mobile App ....................................................................................................................................................7 Registration, Badges, and Pre-ordered T-shirts .............................................................................................7 Oral Presenters: Speaker Ready Room - Camellia 4.......................................................................................7 Poster Sessions and Exhibits - Prince George’s Exhibition Hall ......................................................................7 GSA Central - Booth 520 ................................................................................................................................8 Internet Access ..............................................................................................................................................8 -

Abstracts from the 10Th World Congress for Microcirculation

DOI:10.1111/micc.12246 Abstracts Abstracts from the 10th World Congress for Microcirculation September 25th – 27th, 2015 Kyoto, Japan PLENARY LECTURES vascular neutrophils that constantly patrol the lung and can detect and phagocytose bacteria attached to endothelium suggesting some communication inter-cellular communica- PL1 tion. Clearly much anti-microbial activity occurs in the Imaging the microcirculation in infections vasculature prior to dissemination of bacteria into tissues. P Kubes University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada PL2 Using spinning disk microscopy has allowed us to track pathogens and immune cells in the microcirculation. Mapping oxygen in the brain of awake resting Observing the liver microvasculature revealed numerous mice immune speed bumps that slowed, delayed and even S Charpak prevented bacteria from disseminating to other organs. For Laboratory of Neurophysiology and New Microscopies, Inserm U1128, example, when Borrelia burgdorferi enters the vasculature Paris Descartes University, Paris, France they are immediately caught by the liver vascular macro- The brain is extremely sensitive to hypoxia. Yet, the phage, the Kupffer cells and are engulfed and antigens are physiological values of oxygen concentration in the brain presented on CD1d to resident vascular immune cells remain elusive because high resolution measurements have including invariant Natural Killer T cells (iNKT cells). These only been performed during anesthesia, which affects two iNKT cells receive messages and rapidly make gamma main parameters modulating tissue oxygenation, i.e. interferon to help with immunity. Absence of these events neuronal activity and cerebral blood flow. Using the recent leads to massive dissemination of borrelia especially to joints. finding that measurements of capillary erythrocyte-associ- In the joints the iNKT cells live closely apposed but outside ated transients i.e. -

Modeling Osteoclast Defect and Altered Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche in Osteopetrosis with Patient-Derived Ipscs

Modeling Osteoclast Defect and Altered Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche in Osteopetrosis with Patient-Derived iPSCs Inci Cevher Zeytin Hacettepe University Berna Alkan Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi Cansu Ozdemir Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi Duygu Cetinkaya Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi FATMA VISAL OKUR ( [email protected] ) Hacettepe University, Faculty of Medicine https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1679-6205 Research Keywords: Osteopetrosis, TCIRG1, iPSC, disease modeling, osteoclast, niche modeling, HSC Posted Date: March 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-258821/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/22 Abstract Background Patients with osteopetrosis present with defective bone resorption caused by the lack of osteoclast activity and hematopoietic alterations, but their bone marrow hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell and osteoclast contents might be different. Osteoclasts recently have been described as the main regulators of HSCs niche, however, their exact role remains controversial due to the use of different models and conditions. Investigation of their role in hematopoietic stem cell niche formation and maintenance in osteopetrosis patients would provide critical information about the mechanisms of altered hematopoiesis. We used patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model osteoclast defect and hematopoietic niche compartments in vitro. Methods iPSCs were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients carrying TCIRG1 mutation. iPSC lines were differentiated rst into hematopoietic stem cells-(HSCs), and then into myeloid progenitors and osteoclasts using a step-wise protocol. Then, we established different co-culture conditions with bone marrow-derived hMSCs and iHSCs of osteopetrosis patients as an in vitro hematopoietic niche model to evaluate the interactions between osteopetrotic-HSCs and bone marrow- derived MSCs as osteogenic progenitor cells. -

Functional Analysis of Somatic Mutations Affecting Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Family in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on March 29, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0582 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Functional analysis of somatic mutations affecting receptor tyrosine kinase family in metastatic colorectal cancer Leslie Duplaquet1, Martin Figeac2, Frédéric Leprêtre2, Charline Frandemiche3,4, Céline Villenet2, Shéhérazade Sebda2, Nasrin Sarafan-Vasseur5, Mélanie Bénozène1, Audrey Vinchent1, Gautier Goormachtigh1, Laurence Wicquart6, Nathalie Rousseau3, Ludivine Beaussire5, Stéphanie Truant7, Pierre Michel8, Jean-Christophe Sabourin9, Françoise Galateau-Sallé10, Marie-Christine Copin1,6, Gérard Zalcman11, Yvan De Launoit1, Véronique Fafeur1 and David Tulasne1 1 Univ. Lille, CNRS, Institut Pasteur de Lille, UMR 8161 - M3T – Mechanisms of Tumorigenesis and Target Therapies, F-59000 Lille, France. 2 Univ. Lille, Plateau de génomique fonctionnelle et structurale, CHU Lille, F-59000 Lille, France 3 TCBN - Tumorothèque Caen Basse-Normandie, F-14000 Caen, France. 4 Réseau Régional de Cancérologie – OncoBasseNormandie – F14000 Caen – France. 5 Normandie Univ, UNIROUEN, Inserm U1245, IRON group, Rouen University Hospital, Normandy Centre for Genomic and Personalized Medicine, F-76000 Rouen, France. 6 Tumorothèque du C2RC de Lille, F-59037 Lille, France. 7 Department of Digestive Surgery and Transplantation, CHU Lille, Univ Lille, 2 Avenue Oscar Lambret, 59037, Lille Cedex, France. 8 Department of hepato-gastroenterology, Rouen University Hospital, Normandie Univ, UNIROUEN, Inserm U1245, IRON group, F-76000 Rouen, France. 9 Department of Pathology, Normandy University, INSERM 1245, Rouen University Hospital, F 76 000 Rouen, France. 10 Department of Pathology, MESOPATH-MESOBANK, Centre León Bérard, Lyon, France. 11 Thoracic Oncology Department, CIC1425/CLIP2 Paris-Nord, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, Paris, France. -

Survival B Ligand-Induced Osteoclast

MIP-1γ Promotes Receptor Activator of NF-κ B Ligand-Induced Osteoclast Formation and Survival This information is current as Yoshimasa Okamatsu, David Kim, Ricardo Battaglino, of September 24, 2021. Hajime Sasaki, Ulrike Späte and Philip Stashenko J Immunol 2004; 173:2084-2090; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2084 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/173/3/2084 Downloaded from References This article cites 29 articles, 14 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/173/3/2084.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on September 24, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2004 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology MIP-1␥ Promotes Receptor Activator of NF-B Ligand-Induced Osteoclast Formation and Survival1 Yoshimasa Okamatsu,*† David Kim,* Ricardo Battaglino,* Hajime Sasaki,* Ulrike Spa¨te,* and Philip Stashenko2* Chemokines play an important role in immune and inflammatory responses by inducing migration and adhesion of leukocytes, and have also been reported to modulate osteoclast differentiation from hemopoietic precursor cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. -

Theranostics Deficiency of ATP6V1H Causes Bone Loss by Inhibiting

Theranostics 2016, Vol. 6, Issue 12 2183 Ivyspring International Publisher Theranostics 2016; 6(12): 2183-2195. doi: 10.7150/thno.17140 Research Paper Deficiency of ATP6V1H Causes Bone Loss by Inhibiting Bone Resorption and Bone Formation through the TGF-β1 Pathway Xiaohong Duan1*, Jin Liu1*, Xueni Zheng1*, Zhe Wang1, Yanli Zhang1, Ying Hao1, Tielin Yang2, Hongwen Deng3 1. State Key Laboratory of Military Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Department of Oral Biology, Clinic of Oral Rare and Genetic Diseases, School of Stomatology, The Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, 710032, People’s Republic of China. 2. Key Laboratory of Biomedical Information Engineering of Ministry of Education, and Institute of Molecular Genetics, School of Life Science and Technology, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, People’s Republic of China. 3. School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA. *Contributed equally to this work. Corresponding author: Xiaohong Duan, State Key Laboratory of Military Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Department of Oral Biology, Clinic of Oral Rare and Genetic Diseases, School of Stomatology, the Fourth Military Medical University, 145 West Changle Road, Xi’an 710032, P. R. China. Tel: 86-29-84776169; Fax: 86-29-84776169; E-mail: [email protected]. © Ivyspring International Publisher. Reproduction is permitted for personal, noncommercial use, provided that the article is in whole, unmodified, and properly cited. See http://ivyspring.com/terms for terms and conditions. Received: 2016.08.08; Accepted: 2016.08.15; Published: 2016.09.13 Abstract Vacuolar-type H +-ATPase (V-ATPase) is a highly conserved, ancient enzyme that couples the energy of ATP hydrolysis to proton transport across vesicular and plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells.