BAGHDAD's FALL and ITS AFTERMATH Contesting The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol

Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Summer 2003), pp. 128-149 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.128 . Accessed: 25/03/2015 15:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 66.134.128.11 on Wed, 25 Mar 2015 15:58:14 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions QUARTERLY UPDATE ON CONFLICT AND DIPLOMACY 16 FEBRUARY–15 MAY 2003 COMPILED BY MICHELE K. ESPOSITO The Quarte rlyUp date is asummaryofbilate ral, multilate ral, regional,andinte rnationa l events affecting th ePalestinians andth efutureofth epeaceprocess. BILATERALS 29foreign nationals had beenkilled since 9/28/00. PALESTINE-ISRAEL Positioningf orWaronIraq Atthe opening of thequarter, Ariel Tokeep up the appearance of Sharon had beenreelected PM of Israel movementon thepeace process in the and was in theprocess of forming a run-up toawar on Iraq, theQuartet government.U.S. -

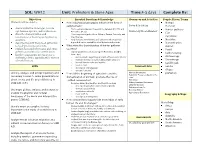

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 Days Complete

SOL: WHI.2 Unit: Prehistory & Stone Ages Time:4-5 days Complete By: Objectives Essential Questions & Knowledge Resources and Activities People, Places, Terms Students will be able to: How did physical geography influence the lives of Nomad early humans? Notes & Activities Hominid characterize the stone ages, bronze Homo sapiens emerged in east Africa between 100,000 and Hunter-gatherer age, human species, and civilizations. 400,000 years ago. Prehistory Vocab Handout Clan describe characteristics and Homo sapiens migrated from Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and innovations of hunting and gathering the Americas. Paleolithic societies. Early humans were hunters and gatherers whose survival Neolithic describe the shift from food gathering depended on the availability of wild plants and animals. Domestication to food-producing activities. What were the characteristics of hunter gatherer Artifact explain how and why towns and cities societies? Fossil grew from early human settlements. Hunter-gatherer societies during the Paleolithic Era (Old Carbon dating list the components necessary for a Stone Age) Archaeology civilization while applying their themes o were nomadic, migrating in search of food, water, shelter of world history. o invented the first tools, including simple weapons Stonehenge o learned how to make and use fire Catal hoyuk Skills o lived in clans Internet Links Jericho o developed oral language o created “cave art.” Aleppo Human Organisms Identify, analyze, and interpret primary and How did the beginning of agriculture and the prehistory Paleolithic Era versus Neolithic Era secondary sources to make generalizations domestication of animals promote the rise of chart about events and life in world history to settled communities? Prehistory 1500 A.D. -

Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Terhadap Negeri- Negeri Muslim Pada Masa Dinasti Ilkhan (1260-1343)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-Jurnal UIN (Universitas Islam Negeri) Alauddin Makassar Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Budi dan Nita (1260-1343) POLITIK PENGUASAAN BANGSA MONGOL TERHADAP NEGERI- NEGERI MUSLIM PADA MASA DINASTI ILKHAN (1260-1343) Budi Sujati dan Nita Yuli Astuti Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung Email: [email protected] Abstract In the history of Islam, the destruction of the Abbasid dynasty as the center of Islamic civilization in its time that occurred on February 10, 1258 by Mongol attacks caused Islam to lose its identity.The destruction had a tremendous impact whose influence could still be felt up to now, because at that time all the evidence of Islamic relics was destroyed and burnt down without the slightest left.But that does not mean that with the destruction of Islam as a conquered religion is lost as swallowed by the earth. It is precisely with Islam that the Mongol conquerors who finally after assimilated for a long time were drawn to the end of some of the Mongol descendants themselves embraced Islam by establishing the Ilkhaniyah dynasty based in Tabriz Persia (present Iran).This is certainly the author interest in describing a unique event that the rulers themselves who ultimately follow the beliefs held by the community is different from the conquests of a nation against othernations.In this study using historical method (historical study) which is descriptive-analytical approach by using as a medium in analyzing. So that events that have happened can be known by involving various scientific methods by using social science and humanities as an approach..By using social science and humanities will be able to answer events that happened to the Mongols as rulers over the Muslim world make Islam as the official religion of his government to their grandchildren. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

The Coins of the Later Ilkhanids

THE COINS OF THE LATER ILKHANIDS : A TYPOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 BY SHEILA S. BLAIR Ghazan Khan was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Ilkhanid rulers of Persia: not only a commander and statesman, he was also a linguist, architect and bibliophile. One of his most lasting contribu- tions was the reorganization of Iran's financial system. Upon his accession to the throne, the economy was in total chaos: his prede- cessor Gaykhatf's stop-gap issue of paper money to fill an empty treasury had been a fiasco 2), and the civil wars among Gaykhatu, Baydu, and Ghazan had done nothing to restore trade or confidence in the economy. Under the direction of his vizier Rashid al-Din, Ghazan delivered an edict ordering the standardization of the coinage in weight, purity, and type 3). Ghazan's standard double-dirham became the basis of Iran's monetary system for the next century. At varying intervals, however, the standard type was changed: a new shape cartouche was introduced, with slight variations in legend. These new types were sometimes issued at a modified weight standard. This paper will analyze the successive standard issues of Ghazan and his two successors, Uljaytu and Abu Said, in order to show when and why these new types were introduced. Following a des- cription of the successive types 4), the changes will be explained through 296 an investigation of the metrology and a correlation of these changes in type with economic and political history. Another article will pursue the problem of mint organization and regionalization within this standard imperial system 5). -

Il-Khanate Empire

1 Il-Khanate Empire 1250s, after the new Great Khan, Möngke (r.1251–1259), sent his brother Hülegü to MICHAL BIRAN expand Mongol territories into western Asia, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel primarily against the Assassins, an extreme Isma‘ilite-Shi‘ite sect specializing in political The Il-Khanate was a Mongol state that ruled murder, and the Abbasid Caliphate. Hülegü in Western Asia c.1256–1335. It was known left Mongolia in 1253. In 1256, he defeated to the Mongols as ulus Hülegü, the people the Assassins at Alamut, next to the Caspian or state of Hülegü (1218–1265), the dynasty’s Sea, adding to his retinue Nasir al-Din al- founder and grandson of Chinggis Khan Tusi, one of the greatest polymaths of the (Genghis Khan). Centered in Iran and Muslim world, who became his astrologer Azerbaijan but ruling also over Iraq, Turkme- and trusted advisor. In 1258, with the help nistan, and parts of Afghanistan, Anatolia, of various Mongol tributaries, including and the southern Caucasus (Georgia, many Muslims, he brutally conquered Bagh- Armenia), the Il-Khanate was a highly cos- dad, eliminating the Abbasid Caliphate that mopolitan empire that had close connections had nominally led the Muslim world for more with China and Western Europe. It also had a than 500 years (750–1258). Hülegü continued composite administration and legacy that into Syria, but withdrew most of his troops combined Mongol, Iranian, and Muslim after hearing of Möngke’s death (1259). The elements, and produced some outstanding defeat of the remnants of his troops by the cultural achievements. -

View a Copy of This Licence, Visit

Ibrayeva et al. Herit Sci (2021) 9:90 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00564-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Interdisciplinary approach to studying written nomadic sources in the context of modern historiology Akmaral Ibrayeva1* , Assemgul Temirkhanova2, Zaure Kartova1, Tlegen Sadykov2, Nurbolat Abuov1 and Anatoliy Pleshakov1 Abstract This article uses an interdisciplinary approach to analyze textual sources from nomadic civilization. Linguistic analysis has been increasingly used due to the emergence of a huge array of autochthonous and authentic written sources. It is impossible to extract the necessary historical information from those sources without using a new research method. This study aims to apply discourse analysis to medieval textual sources called edicts published in 1400–1635 by the leaders of the Central Asian states. This approach is expected to enable a detailed study of the structure of edicts, as well as speech patterns and terms used in the text. The results of the study revealed the structure of the examined edicts, as well as socio-cultural, economic, and communicative features of the nomadic society. First, the discourse repertoire of Edicts from Sygnak is rather unique, as evidenced by comparative analysis of patents from the cities of Sygnak, Sayram and Turkestan located in the Syr Darya basin. Second, edicts in this study refect the result of the mutual infuence of sedentary and mobile lifeways. Third, the arguments behind certain speech patterns used in the examined edicts emerged under the infuence of Turkic traditions. Keywords: Discourse analysis, Document structure, Edicts, Nomadic civilization, Oral historiology Introduction documents with the content and legal form characteristic One of the major challenges of nomadic research is the to contracts. -

The Seljuks of Anatolia: an Epigraphic Study

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2017 The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study Salma Moustafa Azzam Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Azzam, S. (2017).The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 MLA Citation Azzam, Salma Moustafa. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An Epigraphic Study Abstract This is a study of the monumental epigraphy of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, also known as the Sultanate of Rum, which emerged in Anatolia following the Great Seljuk victory in Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in the year 1071.It was heavily weakened in the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 against the Mongols but lasted until the end of the thirteenth century. The history of this sultanate which survived many wars, the Crusades and the Mongol invasion is analyzed through their epigraphy with regard to the influence of political and cultural shifts. The identity of the sultanate and its sultans is examined with the use of their titles in their monumental inscriptions with an emphasis on the use of the language and vocabulary, and with the purpose of assessing their strength during different periods of their realm. -

Altin Orda Devleti'nde Yerleşik Hayatin Ilk Izleri

Cilt/Volume 3, Sayı/Issue 6, Temmuz/July 2021, ss. 229-240. Geliş Tarihi–Received Date: 18.03.2021 Kabul Tarihi–Accepted Date: 08.05.2021 ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESİ – RESEARCH ARTICLE ALTIN ORDA DEVLETİ’NDE YERLEŞİK HAYATIN İLK İZLERİ: SARAY ŞEHRİ FATİH BOSTANCI∗ ÖZ Çinggiz Han Moğol kabilelerini bileştirip devletini tesis ettikten sonra hanlığının on dördüncü yılında Batı Seferlerini başlattı. Bu seferler oğlu Cuci Han’ın kumandasında Cebe ve Sübütey Noyanların yardımlarıyla Moğol Devleti’nin Kuzey Batısı’na yapıldı. Seferler başarıyla tamamlanmış bunun sonucunda Azerbaycan topraklarını da içine alan batı toprakları Cuci Han’a bırakıldı. Çinggiz Han’dan önce ölen Cuci Han’ın topraklarına oğlu Batu Han ve kendisinden sonra gelenler sahip çıktılar. Çinggiz Han’ın ölümünden sonra Moğol Devleti’nin başına geçen Ögedey Han zamanında İkinci Batı Seferleri başlatıldı. Bu seferler yine Cuci Ulusu’nun komutasında gerçekleşti. Bu kez Moğol ordularının başında Batu Han ve yanında Cebe ve Sübütey Noyan yer aldı. İkinci Batı Seferleri neticesinde büyük bir alana yayılan Moğol Devleti, Rusya topraklarının büyük bir kısmını da ele geçirdi. Batu Han bu sefer sonucunda dedesi Çinggiz Han hayatta iken kendisinden elde etmiş olduğu Altın Busagalı Ak-Orda’nın temellerini Rusya topraklarında bulunan bugünkü Aktübe bölgesinde Saray adını verdiği şehirle attı. Bu devlete Altın Orda denildi. Çeşitli kaynaklarda farklı isimlerle anılan bu devlet birçok defa Cuci Ulusu şeklinde anılırken, bazen de başında bulunan hükümdarın adıyla anıldı. Batu Han Saray şehrini ilk kurduğu zaman Büyük Moğol Devleti’nin Kara-Kurum’daki Ordası’na benzer bir yapıda kurdu. Şehirleşme adına önemli teşebbüsleri olan Batu Han’dan sonra gelişim ve genişlemeye önem veren kardeşi Berke Han hükümdar oldu.