Carnevale Di Venezia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Venice Carnival Special Projects Case History

Carnival of Venice 2016 23 January – 9 February From January, 23 To February, 9 Venice historical Centre, islands, Mestre, Marghera Number of visitors: more than 1.000.000 attendants, with daily peaks of 150.000 persons Programm of Carnival 2015 18 days of events and celebrations: from the prologue to the Mardi Gras (Shrove Tuesday) that marks the grand finale of the gala. Crowds are expected to peak during the three weekends of the event (January 23-24 and 30-31, February 6-7), the Thursday before Lent (February 4) and Mardi Gras (February 9). Program: the highlights Prologue (January 23-24): the official opening of the Carnival with the “Festa Veneziana” in Cannaregio, made of a water parade of rowers in costume and food tasting. First weekend (January 30-31): the Volo dell’Angelo, the Festa delle Marie (that recalls a historical event elaborating it in the form of a beauty contest in Renaissance costumes), the historical re-enactments. Second weekend (6-7 February): final of the best masked costume contest, the “commedia dell’arte” shows, music concerts, the “volo dell’Asino” in Mestre. For the whole period of the carnival: daily shows for the best masked costume contest, cultural events (itineraries and nighttime visits to museums and cultural seats in the city, exhibitions, readings, ecc.), dj-set. Let’s all spend marvellous Carnival nights at the Arsenal! The Arsenal dresses up in magic, poetry, music and sensational special effects on water and turns into Carnival at the Arsenal. Music and traveling entertainment will be introduced by a magic show. -

Accepted Manuscript Version

Research Archive Citation for published version: Kim Akass, and Janet McCabe, ‘HBO and the Aristocracy of Contemporary TV Culture: affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007’, Mise au Point, Vol. 10, 2018. DOI: Link to published article in journal's website Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: This manuscript version is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives License CC BY NC-ND 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact Research & Scholarly Communications at [email protected] 1 HBO and the Aristocracy of TV Culture : affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007 Kim Akass and Janet McCabe In its institutional pledge, as Jeff Bewkes, former-CEO of HBO put it, to ‘produce bold, really distinctive television’ (quoted in LaBarre 90), the premiere US, pay- TV cable company HBO has done more than most to define what ‘original programming’ might mean and look like in the contemporary TV age of international television flow, global media trends and filiations. In this article we will explore how HBO came to legitimatise a contemporary television culture through producing distinct divisions ad infinitum, framed as being rooted outside mainstream commercial television production. In creating incessant divisions in genre, authorship and aesthetics, HBO incorporates artistic norms and principles of evaluation and puts them into circulation as a succession of oppositions— oppositions that we will explore throughout this paper. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

NAME E-Book 2012

THE HISTORY OF THE NAME National Association of Medical Examiners Past Presidents History eBook 2012 EDITION Published by the Past Presidents Committee on the Occasion of the 46th Annual Meeting at Baltimore, Maryland Preface to the 2012 NAME History eBook The Past Presidents Committee has been continuing its effort of compiling the NAME history for the occasion of the 2016 NAME Meeting’s 50th Golden Anniversa- ry Meeting. The Committee began collecting historical materials and now solicits the histories of individual NAME Members in the format of a guided autobiography, i.e. memoir. Seventeen past presidents have already contributed their memoirs, which were publish in a eBook in 2011. We continued the same guided autobiography format for compiling historical ma- terial, and now have additional memoirs to add also. This year, the book will be combined with the 2011 material, and some previous chapters have been updated. The project is now extended to all the NAME members, who wish to contribute their memoirs. The standard procedure is also to submit your portrait with your historical/ memoir material. Some of the memoirs are very short, and contains a minimum information, however the editorial team decided to include it in the 2012 edition, since it can be updated at any time. The 2012 edition Section I – Memoir Series Section II - ME History Series – individual medical examiner or state wide system history Presented in an alphabetic order of the name state Section III – Dedication Series - NAME member written material dedicating anoth- er member’s contributions and pioneer work, or newspaper articles on or dedicated to a NAME member Plan for 2013 edition The Committee is planning to solicit material for the chapters dedicated to specifi- cally designated subjects, such as Women in the NAME, Standard, Inspection and Accreditation Program. -

Batman2 Script

BATMAN TRIUMPHANT by “The Guard” 2003 Batman created by Bob Kane 2. The WARNER BROTHERS logo appears onscreen. Ominous notes sound. The logo morphs into a Bat-Emblem. Dark skies fade in around it. Brilliant blue light emanates from the Bat-Emblem, blinding us. BATMAN TRIUMPHANT FADE IN GOTHAM CITY-DUSK An aerial view of Gotham. Ancient architecture has mixed with the new millennium. The result: architecture that combines stone cathedrals and shining towers of glass and steel. Hundreds of cars, taxis, and buses cruise along the streets below, and a siren echoes from somewhere. SUPER TEXT: GOTHAM CITY CUT TO: EXT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM-DUSK A huge stone building set behind a large set of stone stairs. The bank building has a windowless exterior, with wide glass entrance doors. Several GOTHAMITES are going in and out. CUT TO: INT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM About 20 Gothamites are waiting in line in front of old- fashioned, gated bank windows. We can hear Classical music in the background. CUT TO: EXT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM-DUSK A black Hummer pulls to a perfect stop in front of the bank. Almost on cue, the doors open, and seven THUGS climb out of the Hummer. All of them wear black leather and ski masks. Two of them have submachine guns. 3. The other five have duffel bags and gas masks. The men turn as a back door on the vehicle starts to open. FADE TO: INT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM The front doors burst open and the seven thugs enter. -

Interrogations and Confessions

CHAPTER 16 INTERROGATIONS AND CONFESSIONS Did the police constitutionally obtain the defendant’s confession to murder? Dr. Jeffrey Metzner, a psychiatrist employed by the state hospital, testified that respondent was suffering from chronic schizophrenia and was in a psychotic state at least as of August 17, 1983, the day before he confessed. Metzner’s interviewsdistribute with respondent revealed that respondent was following the “voice of God.” This voice instructed respondent to withdraw money from the bank, to buy an airplane ticket, and to fly from Boston to Denver. When respondent arrived from Boston, God’s voice became stronger and told respondent either to confess to the killing or to commit suicide. Reluctantly following the command of the voices, respondent approached Officeror [Patrick] Anderson and confessed. Dr. Metzner testified that, in his expert opinion, respondent was experiencing “command hallucinations.” This condition interfered with respondent’s “volitional abilities; that is, his ability to make free and rational choices.” (Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157 [1986]) CHAPTER OUTLINE post, Introduction Case Analysis Due Process Chapter Summary The Right Against Self-Incrimination Chapter Review Questions Miranda v. Arizona copy, Legal Terminology Sixth Amendment Right to Counsel: Police Interrogations not DoTEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE 1. Do you know the role of confessions in the criminal investigation process, the potential challenges and problems presented by confessions, and the explanations for false confessions? 2. Are you able to discuss the protections provided by the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and what is protected by the Fifth Amendment and what is not protected? 3. Can you explain how Miranda v. -

View Entire Issue As

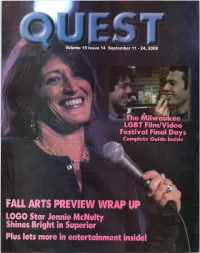

Volume 15 Issue 14 September 11 - 24, 2008 The Milwau ee LGBT Film/Video Festival Final Days • Complete Guide Inside iR i t Orf LIM nI ' i FALL ARTS PREVIEW WRAP UP LOGO Star Jennie McNulty Shines Bright in Superior Plus lots more in entertainment inside! WHY BE SHY? GET TESTED for HIV, at BESTD Clinic. It's free and it's fast, with no names and no needles.We also provide free STD testing, exams, and treatment. Staffed totally by volunteers and supported by donations, BESTD has been doing HIV outreach since 1987. We're open: Mondays 6 PM-8:30 PM: Free HIV & STD testing Tuesdays 6 PM-8:30 PM: All of the above plus STD exams and treatment Some services only available for men; visit our web site for details. BESTD cum(' Brady East STD Clinic 1240 E. Brady Street Milwaukee, WI 53202 414-272-2144 www.bestd.org DIES "Legal couple status may support a relationship," LESBIAN RIGHTS PIONEER DEL MARTIN researcher Robert-Jay Green said in a statement an- Lesbian Rights Pioneer Del Mar- things. nouncing the findings. tin Dies "I also never imagined there Surprise! Log Cabin Republicans Endorse Mc- San Francisco - Just two months would be a day that we would ac- Cain-Palhi Ticket: The Log Cabin Republicans after achieving a life-long dream, tually be able to get married," Lyon (LCR), who refused to endorse George W. Bush for the legal marriage to her partner of wrote. "I am devastated, but I take reelection in 2004, announced their endorsement of 55 years, lesbian rights pioneer Del some solace in knowing we were Senator John McCain for President of the United Martin - whose trailblazing activism able to enjoy the ultimate rite of States on September 2: LCR's board of directors spanned more than a half century - love and commitment before she voted 12-2 to endorse both McCain and Alaska Gov- died August 27 at a local hospice. -

22 Innovation Cases

22 INNOVATION CASES in Micro, Small, Medium and Large-sized Enterprises 22 INNOVATION CASES in Micro, Small, Medium and Large-sized Enterprises CNI – National Confederation of Industry Brazil Robson Braga de Andrade President SESI – Social Service of Industry Robson Braga de Andrade Director SENAI – National Service of Industrial Training Rafael Esmeraldo Lucchesi Ramacciotti General-Director SEBRAE – Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service Guilherme Afif Domingos President 22 INNOVATION CASES in Micro, Small, Medium and Large-sized Enterprises Brasília 2017 © 2017. CNI – National Confederation of Industry. © 2017. SESI – Social Service of Industry. © 2017. SENAI – National Service of Industrial Training. © 2017. SEBRAE – Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, provided the source is cited. CNI Innovation Board – DI SEBRAE Technical Board – DITEC CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA C748i National Confederation of Industry. Innovate to add value. 22 innovation cases in micro, small, medium and large-sized enterprises / National Confederation of Industry, Social Service for Industry, National Service of Industrial Learning, Brazilian Service of Support to Micro and Small-Sized Enterprises. Brasília: CNI, 2017. 272p. : il. 1.Innovation. 2. Micro, small, medium, and large-sized enterprises. I. Title. CDU: 347.77 CNI SEBRAE National Confederation of Industry Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service Headquarters Setor Bancário Norte Headquarters Quadra 1 – Bloco C SGAS -

Chalearn Looking at People 2015 Challenges: Action Spotting and Cultural Event Recognition

ChaLearn Looking at People 2015 challenges: action spotting and cultural event recognition Xavier Baro´ Jordi Gonzalez` Universitat Oberta de Catalunya - CVC Computer Vision Center (UAB) [email protected] [email protected] Junior Fabian Miguel A. Bautista Computer Vision Center (UAB) Universitat de Barcelona [email protected] [email protected] Marc Oliu Hugo Jair Escalante Isabelle Guyon Universitat de Barcelona INAOE Chalearn [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sergio Escalera Universitat de Barcelona - CVC [email protected] Abstract CVPR workshop on action/interaction spotting and cultural event recognition. The recognition of continuous, natural Following previous series on Looking at People (LAP) human signals and activities is very challenging due to the challenges [6, 5, 4], ChaLearn ran two competitions to multimodal nature of the visual cues (e.g., movements of be presented at CVPR 2015: action/interaction spotting fingers and lips, facial expression, body pose), as well as and cultural event recognition in RGB data. We ran a technical limitations such as spatial and temporal resolu- second round on human activity recognition on RGB data tion. In addition, images of cultural events constitute a very sequences. In terms of cultural event recognition, tens challenging recognition problem due to a high variability of categories have to be recognized. This involves scene of garments, objects, human poses and context. Therefore, understanding and human analysis. This paper summa- how to combine and exploit all this knowledge from pixels rizes the two challenges and the obtained results. De- constitutes a challenging problem. tails of the ChaLearn LAP competitions can be found at http://gesture.chalearn.org/. -

Carnival Scratch-Art® Mask

Carnival Scratch-Art® Mask (art + social studies) Explore the history of carnival masks from various cultures, such as Mardi Gras in New Materials Orleans, the Carnival of Venice and “Commedia Scratch Art® Clear-Scratch™ Film Dell'arte” in Italy. Ornate and colorful masks are (13524-1030), package of 30 sheets, ® easy to create with Scratch -Art Clear-Scratch™ need 1/2 sheet per demi-mask, full sheet for film and permanent Sharpie® markers. full-face mask Grade Levels K-8 Sharpie Chisel-Tip Markers, set of 8 colors Note: instructions and materials based on a (21383-0089), share one set between 4-5 class of 25 students. Adjust as needed. students Preparation Scratch Sticks (14907-1045), package of 100, need one per student 1. Cut sheets of Scratch Art® Clear- Scratch™ film in half to make 8" x 4.75" Wood Dowel, 1/4" dia x 12" (60448-1412) pieces. Will need one piece per mask package of 12, need one per mask ® 2. Draw a mask shape on paper and cut out Blick E-Z Grip Knife (57419-2980), one or to use as a template. For demi-mask, use two per class the pattern on page 2. Optional Process Krylon® Low-Odor Spray Finish (23710-1001), 1. Trace the mask shape onto the matte gloss, 11-oz can, need one side of the film lightly with a pencil. Extra features, such as ears, hair, antennae, etc. can be added to the basic clear plastic surface. Place a plain white mask shape if desired. Cut mask out of sheet of paper beneath the mask while film (do not cut out eye areas). -

Progressive English III

1 PREPARATORIA 22 Portfolio of Evidences 2nd Opportunity Progressive English III Student’s name: __________________________________________________ Student´s number: ________________ Date: _____/ ______ / 2020 Teacher: _________________________________________ Group: _________ This portfolio is part of 60% of your qualification. This value will be obtained as long as it meets the following requirements: 1. Transcribed by hand, in its entirety and with the correct answers. 2. Complete identification data. 3. This portfolio must be uploaded in PDF extension, only on the day and at the time of the exam in the Tasks section of your team corresponding to the subject in MS Teams, where your teacher will review it. 4. PLEASE ANSWER ONLY WITH BLUE INK AND ADD YOUR NAME ON EACH SHEET. Elaborated by M.C.C. Patricia Karina Perez Burgos. 2 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE NUEVO LEÓN PREPARATORIA NO. 22 PORTFOLIO OF EVIDENCE PROGRESSIVE ENGLISH III SECOND OPORTUNITY NAME: _______________________________________________________________ GROUP:_______________________________________________________________ DATE:________________________________________________________________ Elaborated by M.C.C. Patricia Karina Perez Burgos. 3 Conditional sentences are often divided into different types. 1. Zero conditional. We use the zero conditional to talk about things that are generally true, especially for laws and rules. ... 2. First conditional. We use the first conditional when we talk about future situations we believe are real or possible. ... The first conditional describes a particular situation, whereas the zero conditional describes what happens in general. I.- Read the following pairs of sentences in zero and first conditionals, and choose the ones that are written correctly. 1.- (a) The table will break if you sit on it. (b) The table will break, if you sit on it. -

Department of Music Programs 1972 - 1973 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 1973 Department of Music Programs 1972 - 1973 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1972 - 1973" (1973). School of Music: Performance Programs. 6. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 8 0 .7 3 9 0£4p 1 9 7 2 -7 3 PROGRAMS 1972 1973 DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC yuvet Nazarene College Kankakee. VL OLIVET NAZARENE COLLEGE. DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC p r e s e n ts a STUDENT RECITAL Six E cossaises ........................ .... .......................................... B eeth oven Terry Morsch, piano T raum erei ........................ ........................................ Robert Schumann Important Event Robert Schumann Brad Morsch, piano Caro Mio B e n .......................................... Guiseppe Giordani Cheryl Spargur, soprano Linda Jarnagin, accompanist Art Thou The Christ? ..................... ..... Jeoffrey O'Hara Marla Kensey, soprano Still Wie Die Nacht .............................................................. C