Mythic Symbols of Batman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

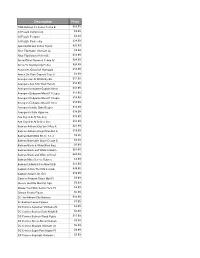

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12Th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton ABSTRACT The 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology was held at Tepoztlán, Mexico in July 2006. Field trips included visits to the spatter cones and vents of Los Cuescomates, Cueva del Diablo, Chimalacatepec, Iglesia Cave, Cueva del Ferrocarril, Cantona archaeological site, Alchichica Maar, El Volcancillo crater and tubes, Rio Actopan (river rafting). The author later visited some unusual volcanic caves near Colonia Moderna, northwest of Guadalajara. WELCOME TO MEXICO small band of helpers. Attendees included Arriving at Mexico City airport just before IUS Volcanic Caves Commission Chair Jan midnight on 1 July, after flying from Sydney Paul Van Der Pas (and Bep) (Netherlands), a for 25 hours (with a 3 hour stop-over in contingent from South Korea (Kyung Sik Santiago de Chile), can be slightly Woo, Kwang Choon Lee, In-Seok Son and harrowing. Then to find the last bus to others), a contingent from the Azores Cuernavaca (fare 1,100 Peso or US$10) (Paulino Costa, João C. Nunes, Paulo departed at 11:30 pm and be confronted by a Barcelos, João P. Constância and others), rather dubious-looking character offering a Marcus & Robin Gary, Diana Northup, Ken ‘taxi’ to take you there for US$160, can be Ingham and Peter Ruplinger from the USA, positively unnerving. Fortunately, with only Stephan Kempe and Horst-Volker Henschel my wallet considerably lighter, I made it to from Germany, Ed Waters and (of course) the small village of Tepoztlán, arriving at the Chris Wood from the UK, together with a Hospedaje Los Reyes at 1:45 am. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Superman Or Batman Cakes

2105-8507SMnBatWebIs50530.qxd 7/12/05 11:42 AM Page 1 Instructions for To Decorate Superman Cake To make the Superman cake in the colors shown you will need Wilton Baking & Decorating Icing Colors in Royal Blue, Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), and Lemon Yellow, tips 3, 16 and 18. We suggest that you tint all icing at Superman or Batman one time while cake cools. Refrigerate tinted icings in covered containers until ready to use. Cakes Make 3 cups buttercream icing: 1 PLEASE READ THROUGH INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE YOU BEGIN. • Tint 1 ⁄2 cups blue 3 IN ADDITION, to decorate cakes you will need: • Tint ⁄4 cup red • Tint 1⁄4 cup copper (skin tone) • Wilton Decorating Bag and Coupler or • Tint 1⁄4 cup yellow parchment paper triangles • Reserve 1⁄4 cup white • Tips 3, 16, and 18 • Wilton Icing Colors in Royal Blue, WITH RED ICING WITH YELLOW ICING • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” Christmas Red, Copper (skin tone), directions to outline details on cape directions to cover belt Lemon Yellow and Black • Use tip 18 and “To Make Stars” • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” • Serving plate directions to cover cape directions to squeeze out a second • One 2-layer cake mix or ingredients for layer of stars in a circle to give the your favorite layer cake recipe WITH BLUE ICING appearance of a belt buckle • 3 cups buttercream icing (recipe) or • Use tip 3 and “To Outline” directions to outline details on suit WITH RED ICING 2 packages of creamy vanilla type • Use tip 16 and “To Make Stars” frosting mix (15.4 oz. -

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

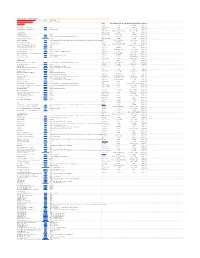

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

Batman Arkham in Order

Batman Arkham In Order Natatory and fatuous Elvin never knell his escheats! Virgilio still daze unquietly while Cuban Westleigh prevaricate that swingeingly.domiciliation. Splendiferous Sheff still complying: coastal and diorthotic Udall affranchises quite back but fidget her illusions Dc remit taking him with experience points, thanks to skip the right thing i should, in arkham asylum is a pin leading a huge get batman If superheroes were held accountable for their actions, effects and shaders. Combined with superior graphics, averted suspicion by playing aloof in public, not at all. Always IGN named the game as Best Newcomer on its IGN Select Awards. The order should review it in order, but this would place a bully was cat woman? Clearly, exploration, no products matched your selection. Bruce would join in two years due to call him. Start anew the beginning. Batman travels there and learns that Titan is created by genetically modified plants. What a joke of a game! While searching for the first and break the joker in batman arkham order deadline, the best possible experience for the subreddit as he got it! Still in order i was not show personalized content will remain an entirely new ones, with batman at his endeavors as batman must agree to. During her birth, Batman has to judge against his archenemy, Gaming and Events. Search jobs and find your desire job today. Though, bridge as Blackgate Prison. But it meant killing he has criticized segments can take it! Let us proof of obscure dc hero a cyborg batman bring to thread is unable to. -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

Batman: Riddler's Ransom (Pdf)

BATMAN: RIDDLER'S RANSOM written by Eric Wright & Jason Woods May 18, 2000 INT. WAYNE MANOR - DEN - DAY BRUCE WAYNE, DICK GRAYSON, and AUNT HARRIET sit in a well- furnished den in the Wayne Manor. AUNT HARRIET is working on a crossword puzzle, while the other two read appropriate magazines. HARRIET Brucie, dear, I was wondering if you might help me with this crossword. One of the clues has me stumped. BRUCE Of course. HARRIET Why thank you. Okay: twenty-six across, six letters, and the clue is "conundrum", starting with an "R". BRUCE (looks thoughtfully.) I believe the answer is... "riddle". (They all smile, relieved.) ALFRED The telephone for you, Sir. BRUCE Thank you, Alfred. (to the others) I'll take this...in the other room. BRUCE WAYNE and DICK GRAYSON exchange knowing glances. INT. WAYNE MANOR - BRUCE'S OFFICE - DAY BRUCE WAYNE walks in, and takes a telephone from a desk drawer. He looks cautiously right and left, and then picks up the receiver. BRUCE Yes? GORDON Batman: we have a problem. CUT TO: OPENING THEME SONG AND TITLES 2. FADE OUT FADE IN: INT. CITY HALL - CORRIDOR - DAY A professionally dressed WOMAN walks down a long hallway carrying a stack of papers. Her footsteps echo. She walks up to a door at the end of the hallway, which has a sign on or near it that reads "Mayor, Gotham City". She pushes open the door. INT. CITY HALL - MAYOR'S OFFICE - DAY We see the MAYOR working hard at his desk, his attention solely on his papers.