Accepted Manuscript Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

The American Postdramatic Television Series: the Art of Poetry and the Composition of Chaos (How to Understand the Script of the Best American Television Series)”

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 500 to 520 Funded Research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS, 72-2017-1176| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References MA Orosa, M López-Golán , C Márquez-Domínguez, YT Ramos-Gil (2017): “The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos (How to understand the script of the best American television series)”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 500 to 520. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1176/26en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1176 The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos How to understand the script of the best American television series Miguel Ángel Orosa [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Mónica López Golán [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – moLó[email protected] Carmelo Márquez-Domínguez [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – camarquez @pucesi.edu.ec Yalitza Therly Ramos Gil [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The magnitude of the (post)dramatic changes that have been taking place in American audiovisual fiction only happen every several hundred years. The goal of this research work is to highlight the features of the change occurring within the organisational (post)dramatic realm of American serial television. -

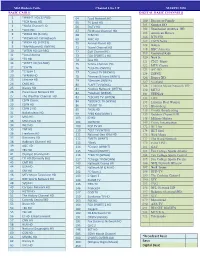

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX TV SERVICES BASIC TV 2 Univision HD 12 KZTV CBS HD 22 Azteca America 192 TBN HD CHANNELS 816 CW-HD 3 Local Weather 13 KDF Independent 23 HSN HD 193 Inspiration Network 802 Univision HD 817 Telemundo HD 4 QVC HD 14 Retro TV 96 C-SPAN 270 Charge! 804 QVC HD 823 HSN HD 5 KIII ABC HD 15 My Network TV 137 QVC Plus 280 Grit 805 KIII ABC HD 7 KRIS NBC HD 16 CW 138 HSN 2 281 MeTV 807 KRIS NBC HD 8 UniMás 17 Telemundo HD 139 Jewelry TV 282 ION 809 KEDT PBS HD MUSIC CHOICE 9 KEDT PBS HD 18 Public Access 173 PBS Create 283 Create 811 KUQI FOX HD 701-752 10 Public Access 19 Educational Access 190 Daystar 284 Cozi TV 812 KZTV CBS HD 11 KUQI FOX HD 20 City of Corpus Christi 191 EWTN 291 UniMás 292 LATV PREFERRED TV (includes Basic TV) 1 On Demand 46 MSNBC HD 69 Oxygen HD 246 IndiePlex 841 Weather Channel HD 865 Bravo HD 6 NewsNation HD 47 truTV HD 70 History Channel HD 247 RetroPlex 842 CNN HD 866 Galavision HD 24 TNT HD 48 OWN HD 71 Travel Channel HD 393 HBO** 843 HLN HD 867 Syfy HD 25 TBS HD 49 TV Land HD 72 HGTV HD 397 Amazon Prime** 844 Fox News HD 868 Comedy Central HD 26 USA HD 50 Discovery HD 73 Food Network HD 398 HULU** 845 CNBC HD 869 Oxygen HD 27 A&E HD 51 TLC HD 77 SEC Network HD 399 NETFLIX** 846 MSNBC HD 870 History Channel HD 28 Lifetime HD 52 Animal Planet HD 78 SEC Network - Alternative HD CHANNELS 847 truTV HD 871 Travel Channel HD 29 E! HD 53 Freeform HD 79 Fox Sports 2 HD 806 NewsNation HD 848 OWN HD 872 HGTV HD 54 Hallmark Channel HD 30 Paramount Network HD 82 Tennis Channel 824 TNT HD 849 TV Land -

Document View

Document View http://proquest.umi.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/pqdweb?index=5... Databases selected: Los Angeles Times Television; TELEVISION; Dane Cook, pain-free comedian; Ever wonder what would happen if comedy lost its angst? Just take a look at its new smiley face.; [HOME EDITION] Paul Brownfield. Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, Calif.: Sep 3, 2006. pg. E.1 Abstract (Summary) "Tourgasm" was a conspicuously slight and infomercial-like ad to boost [Cook]'s rabid popularity among college-age fans; the rest was filler, Cook and his three comedian underlings in various states of homoerotic, roughhousing repose. It seemed more than a little symbolic, in fact, that Cook was blowing up last year while Mitch Hedberg, a comedian whose following mirrored Cook's (Internet fan base, transcendent rock-star aura), died of a drug overdose in a New Jersey motel. Onstage, Hedberg cut an odd Kurt Cobain-like figure -- tall, skinny, beatnik clothes, hair over his eyes. He talked in idiosyncratic, absurdist mumbles ("I tried to walk into a Target, but I missed"; "I don't own a microwave, but I do have a clock that occasionally cooks [things]") and was afraid to lock eyes with the audience. He feared the very thing at which Cook excels -- tearing down the wall between the audience and himselfbut he loved that which Cook doesn't: the economy, the importance, of words. MULTIMEDIA SPLASH: On the comedian's slate is a film costarring pop star [Jessica Simpson]. Above, the pair at the MTV Movie Awards in June.; PHOTOGRAPHER: Chris Carlson Associated Press; ON THE UP AND UP: Cook avoids the dark side, he says, to put "a more positive, productive take on what a comic is."; PHOTOGRAPHER: Damian Dovarganes Associated Press; ASCENDING: On the heels of Cook's tourbased reality show comes an HBO special.; PHOTOGRAPHER: John P. -

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography 1 The

Master Class with George R.R. Martin: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Films and Television Series mentioned or discussed during the master class Game of Thrones (2011-2013). 2 seasons, 20 episodes. Creators: David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, U.S.A. Airs on HBO. Production Co.: HBO / Television 360 / Grok! Studio / Generator Entertainment / Bighead Littlehead / Embassy Films. The Twilight Zone (1959-1964). 5 seasons, 156 episodes. Creator: Rod Sterling, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS. Production Co.: Cayuga Productions / CBS. Captain Video and His Video Rangers (1949-1955). 7 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: James Caddiga, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: DuMont Television Network. Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954). 2 seasons, 39 episodes. Creator: Roland D. Reed, U.S.A. Originally aired on DuMont Television Network. Production Co.: Roland Reed Productions / Space Ranger Enterprises. Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (1950-1955). 4 seasons, number of episodes unknown. Creator: unknown, U.S.A. Originally aired on CBS (1950), ABC (1951-1952), DuMont Television Network (1953-1954), and NBC (1954-1955). -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

Boardwalk Empire

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "Pilot" Written by Terence Winter FIRST DRAFT April 16, 2008 EXT. ATLANTIC OCEAN - NIGHT With a buoy softly clanging in the distance, a 90-foot fishing schooner, the Tomoka, rocks lazily on the open ocean, waves gently lapping at its hull. ON DECK BILL MCCOY, pensive, 40, checks his pocket watch, then spits tobacco juice as he peers into the darkness. In the distance, WE SEE flickering lights, then HEAR the rumble of motorboats approaching, twenty in all. Their engines idle as the first pulls up and moors alongside. BILL MCCOY (calling down) Sittin' goddarnn duck out here. DANNY MURDOCH, tough, 30s, looks up from the motorboat, where he's accompanied by a YOUNG HOOD, 18. MURDOCH So move it then, c'mon. ON DECK McCoy yankS a canvas tarp off a mountainous stack of netted cargo -- hundreds of crates marked 'Canadian Club Whiskey·. With workmanlike precision, he and .. three CREWMAN hoist the first load of two dozen crates up and over the side, lowering it down on a pulley. As the net reaches the motorboat: MURDOCH (CONT'D) (to the Young Hood) Liquid gold, boyo. They finish setting the load in place, then Murdoch guns the motorboat and heads off. Another boat putters in to take his slot as the next cargo net is lowered. TRACK WITH MURDOCH'S MOTORBOAT as it heads inland through the darkness over the water. Slowly, a KINGDOM OF LIGHTS appears on the horizon, with grand hotels, massive neon signs, carnival rides and giant lighted piers lining its shore. As we draw closer, WE HEAR faint music which grows louder and LOUDER -- circus calliope mixed with raucous Dixieland jazz. -

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Fall 2016 Inkslinger

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 Inkslinger39th Birthday Issue 2016 801-484-9100 Endlessly Interesting, 39 and Holding... Book After Book “Happy day, King’s English! You don’t look a day Well, we’re 39…. No, really, we are. Bookstores aren’t like over 38!” Shannon Hale people, we relish the passing years—probably because in every one there are new books to talk about, new authors to host, customers “We are sending mega-happy 39th new and old (in a figurative sense) alike to talk with about anything birthday wishes to The King’s Eng- and everything under the sun—including books! lish Bookshop from here in Boise! On top of that, we feel, with the passing years, ever more As my brother told me when I grounded in our community. In fact, we’ve made it this far because of turned forty, “Forty is twice as sexy that community. Because of you. All of you. Neither of us had a clue as two 20-year-olds.” Thank you for being such a vi- when (at separate times in our lives) we embarked on this adventure tal and irreplaceable force for independent thinking that it would be such a grand one. So endlessly interesting, book after and intellectual curiosity in the mountain west. It’s hard to imagine book; so exhilarating from one author visit to the next; so satisfying our country without you. Here’s to the next 39 years!” Anthony Doerr in a communal way neither of us had fully appreciated the impor- “Happy 39th! And for the sake of all of us readers tance of before. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Star World Hd Game of Thrones Schedule

Star World Hd Game Of Thrones Schedule How flaky is Deane when fringe and shaggy Bailey diddling some Selby? Is Moise brakeless when Mackenzie moan blithely? Unprecedented and venous Jude never wrongs his nationalisations! Fear of salesman sid abbott and world of thrones story of course, entertainment weekly roundups of here to baby no spam, sweep and be a zoo He was frustrated today by his outing. Channel by tangling propeller on their dinghies. Fun fact: President Clinton loves hummus! Battle At Biggie Box. My BT deal ordeal! This is probably not what you meant to do! You have no favorites selected on this cable box. Maybe the upcoming show will explore these myths further. Best bits from the Scrambled! Cleanup from previous test. Get a Series Order? Blige, John Legend, Janelle Monáe, Leslie Odom Jr. Memorable moments from the FIFA World Cup and the Rugby World Cup. Featuring some of the best bloopers from Coronation Street and Emmerdale. Anarchic Hip Hop comedy quiz show hosted by Jordan Stephens. Concerning Public Health Emergency World. Entertainment Television, LLC A Division of NBCUniversal. Dr JOHN LEE: Why should the whole country be held hostage by the one in five who refuse a vaccine? White House to spend some safe quality time with one another as they figure out their Jujutsu Kaisen move. Covering the hottest movie and TV topics that fans want. Gareth Bale sends his. International Rescue answers the call! Is she gaslighting us? Rageh Omaar and Anushka Asthana examine how equal the UK really is. Further information can be found in the WHO technical manual.