2021-08-06 Monthly Reports For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shambel Meressa Advisor

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project By: Shambel Meressa Advisor: Girmay Kahssay (Dr.) A Thesis submitted to the school of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project Shambel Meressa A Thesis Submitted to The School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Shambel Meressa, entitled: “Assessment of potential causes of construction delay in tunnels; a case study at Awash-Weldiya railway project” and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences (Railway Civil Engineering) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Approved by the Examining Committee: Internal Examiner ___________________________ Signature ___________ Date ___________ External Examiner _________________________ Signature____________ Date ____________ Advisor __________________________________ Signature ___________ Date ____________ _____________________________________________________ School or Center Chair Person Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash- Weldiya Railway Project Declaration I declare that this thesis entitled “Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway Project” is my original work. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

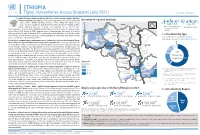

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST in ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE

Mekelle Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST IN ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE December 2012 Millennium Cities Initiative, The Earth Institute Columbia University New York, 2012 DISCLAIMER This publication is for informational This publication does not constitute an purposes only and is meant to be purely offer, solicitation, or recommendation for educational. While our objective is to the sale or purchase of any security, provide useful, general information, product, or service. Information, opinions the Millennium Cities Initiative and other and views contained in this publication participants to this publication make no should not be treated as investment, representations or assurances as to the tax or legal advice. Before making any accuracy, completeness, or timeliness decision or taking any action, you should of the information. The information is consult a professional advisor who has provided without warranty of any kind, been informed of all facts relevant to express or implied. your particular circumstances. Invest in Ethiopia: Focus Mekelle © Columbia University, 2012. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. ii PREFACE Ethiopia, along with 189 other countries, The challenges that potential investors adopted the Millennium Declaration in would face are described along with the 2000, which set out the millennium devel- opportunities they may be missing if they opment goals (MDGs) to be achieved by ignore Mekelle. 2015. The MDG process is spearheaded in Ethiopia by the Ministry of Finance and The Guide is intended to make Mekelle Economic Development. and what Mekelle has to offer better known to investors worldwide. Although This Guide is part of the Millennium effort we have had the foreign investor primarily and was prepared by the Millennium Cities in mind, we believe that the Guide will be Initiative (MCI), which is an initiative of of use to domestic investors in Ethiopia as The Earth Institute at Columbia University, well. -

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility Africa Program Working Paper Series Gilbert M. Khadiagala OCTOBER 2008 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: Elderly women receive ABOUT THE AUTHOR emergency food aid, Agok, Sudan, May 21, 2008. ©UN Photo/Tim GILBERT KHADIAGALA is Jan Smuts Professor of McKulka. International Relations and Head of Department, The views expressed in this paper University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South represent those of the author and Africa. He is the co-author with Ruth Iyob of Sudan: The not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Elusive Quest for Peace (Lynne Rienner 2006) and the welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit editor of Security Dynamics in Africa’s Great Lakes of a well-informed debate on critical Region (Lynne Rienner 2006). policies and issues in international affairs. Africa Program Staff ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS John L. Hirsch, Senior Adviser IPI owes a great debt of thanks to the generous contrib- Mashood Issaka, Senior Program Officer utors to the Africa Program. Their support reflects a widespread demand for innovative thinking on practical IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor solutions to continental challenges. In particular, IPI and Ellie B. Hearne, Publications Officer the Africa Program are grateful to the government of the Netherlands. In addition we would like to thank the Kofi © by International Peace Institute, 2008 Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, which All Rights Reserved co-hosted an authors' workshop for this working paper series in Accra, Ghana on April 11-12, 2008. www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen . i Introduction. 1 Key Challenges . -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Addis Ababa City Structure Plan

Addis Ababa City Structure Plan DRAFT FINAL SUMMARY REPORT (2017-2027) AACPPO Table of Content Part I Introduction 1-31 1.1 The Addis Ababa City Development Plan (2002-2012) in Retrospect 2 1.2 The National Urban System 1.2 .1 The State of Urbanization and Urban System 4 1.2 .2 The Proposed National Urban System 6 1.3 The New Planning Approach 1.3.1 The Planning Framework 10 1.3.2 The Planning Organization 11 1.3.3 The Legal framework 14 1.4 Governance and Finance 1.4.1 Governance 17 1.4.2 Urban Governance Options and Models 19 1.4.3 Proposal 22 1.4.4 Finance 24 Part II The Structure Plan 32-207 1. Land Use 1.1 Existing Land Use 33 1.2 The Concept 36 1.3 The Proposal 42 2. Centres 2.1 Existing Situation 50 2.2 Hierarchical Organization of Centres 55 2.3 Major Premises and Principles 57 2.4 Proposals 59 2.5 Local development Plans for centres 73 3. Transport and the Road Network 3.1 Existing Situation 79 3.2 New Paradigm for Streets and Mobility 87 3.3 Proposals 89 4. Social Services 4.1 Existing Situation 99 4.2 Major Principles 101 4.3 Proposals 102 i 5. Municipal Services 5.1 Existing Situation 105 5.2 Main Principles and Considerations 107 5.3 Proposals 107 6. Housing 6.1 Housing Demand 110 6.2 Guiding Principles, Goals and Strategies 111 6.3 Housing Typologies and Land Requirement 118 6.4 Housing Finance 120 6.5 Microeconomic Implications 121 6.6 Institutional Arrangement and Regulatory Intervention 122 6.7 Phasing 122 7. -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

Reference Map As of 30 May 2018 D

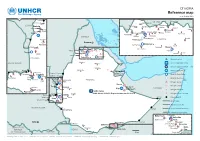

ETHIOPIA Reference map as of 30 May 2018 D Gengen D OMAN Û ERITREA Geresenay Ad-Damazin SAUDI ARABIA Adi-Hageray E" F F Rama Û SUDAN Sheraro Gulomekeda Sherkole Û F Adi-Daero E" Û Dibdibo F AÛ digrat Sherkole #B F E" Ashura Shimelba E" F Dalol AhferomE" F Tsore #B Tsore Shire Wukro Axum F Enticho F Assosa #BShire Endasilassie F F Adwa Û F Ayne Dib Red Sea Shimelba #B AF A Seleklaka ERITREA Hitsats E" Yabus Endabaguna Berahle D ETHIOPIA KhartoBuammbasi Endabaguna #B #B Asmara Sanaa SUDAN YEMEN F Bambasi Adi Harush Embamadre #B F Agula Gure-Shombola #BF Mekelle #B Û Tembien F Û F Û Û F F E" F Mai Tsebri ShimelbaFShire F HimoraE" Û E" E" F F Mekele #B #B F F F F F F Tongo #B AE" Erebti Tongo Endabaguna B Aba'ala F F # Mai Aini #B F F #B F Embamadre MF ekelle ETHIOPIA F National capital Arabian Gondar A Sea SOUTH SUDAN F Alamata F Bure UNHCR Regional Office F A UNHCR Country Office Weldiya F Akula Bahir Dar FF Matar Pagak D F A UNHCR Sub-Office Burbiey D #B Û Djibouti D Nip Nip Wanke F Nguenyiel Bamza / Bameza D Aysaita E" Pamdong DJIBOUTI UNHCR Field Office F F #B Gambella F #B#B Bonga Gizen / Geissan Kule A DÛ Wanthowa F Gengen D UNHCR Field Unit #B Sherkole EÛ " Itang Tierkidi Ad-Damazin ETHIOPIA Jewi Assosa #BE" #B Tsore B Refugee Camp Yabus A # D Sheder Û Abyei #B B#B Tongo # E" Refugee Center Pugnido 2 #B Bambasi Aw-barre #B Gimbi Jijiga A SOMALIA #B Pugnido Tongo F ! Kebribeyah F Refugee Location #B AAG #B Pugnido Addis Ababa Wanke G! Refugee Urban Location Û Addis Ababa UNHCR Representation to AU & ECA Pagak D Bedele Burbiey D D F -

Présentation Powerpoint

African Regional Workshop Evidence-based Approaches to Integrated Planning African Urban Renewal – Experience from the AfDB Infrastructure and Urban Development Department African Development Bank 14 May 2018, Abidjan Infrastructure and Urban Development. Transport, Urban & ICT Implementing more than 116 projects in 44 African countries Active Portfolio 2017 • The Bank’s active Transport & ICT projects portfolio is USD 11.1 billion, with more than 116 projects across 44 countries in Africa. • 37% of the portfolio goes to multi-national projects. Infrastructure and Urban Development. 2 The Urban & Municipal Development Fund (UMDF) a fund design to address gaps and support cities: The Fund’s objective is to support African cities and Improved Urban Planning and management municipalities improve resilience and better manage ex: climate adaptation/mitigation strategies, city urban growth and development by improving planning, development strategies ; infrastructure governance and quality of basic services. investment programs. Improved Project Preparation (ex: pilot Activities The UMDF’s role is catalytic. The fund will enhance projects including climate change, resilient technical assistance and capacity building, with an infrastructure, feasibility and engineering initial focus on global priority areas such as : studies for sustainable urban infrastructure and resilience, mobility and energy efficiency. service delivery. Improved Municipal Governance and finance Technical assistance, training and capacity Each UMDF grants are expected to be modest in size, building programs ; improve access to climate with a foreseen maximum threshold of US$ 1 million per finance, credit facilities, and enhance revenue project. collection. Beneficiaries are key local development institutions including Increased Bank Capacity to support municipalities, development agencies, and government integrated urban development: Finance agencies… analytical studies and knowledge work on emerging issues relevant to Africa. -

USG Humanitarian Programs in Ethiopia

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE ETHIOPIA RESPONSE Last Updated 02/03/20 COUNTRYWIDE iMMAP FAO 0 100 200 mi IOM UNICEF ERITREA 0 100 200 300 km IRC CRS/JEOP FAO OCHA SUDAN WFP UNICEF UNDSS CVT YEMEN UNHAS IRC USFS Adigrat AAH/USA Aksum IRC Concern TIGRAY CRS/JEOP UNICEF FAO Mek’ele ICRC IPC AFAR DRC UNICEF IOM UNICEF Gonder FAO WFP UNHAS CRS/JEOP AMHARA GOAL IMC UNHCR Weldiya Galafi Mercy Corps IRC Bahir Dar DJIBOUTI SCF SCF Asayita Dese BENISHANGUL Bati GUMUZ Debre Markos GOAL Asosa DIRE DAWA WFP Debre Birhan Dire Dawa Tog Wajaale PROGRAM KEY IRC Harar Jijiga USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP Addis Ababa SOMALIA State/PRM HARARI SOUTH SUDAN Nazret Agriculture and Food Security Gambela Metu Cash Transfers for Food WFP Degeh Bur Asela Gore Education AAH/USA Akobo Jima Hosaina OROMIYA SOMALI Gender-Based Violence DCA GAMBELLA Shashemene Prevention and Response DRC Sodo Werder Health Awasa K’ebri Dehar Goba Humanitarian Coordination GOAL SNNP Imi and Information Management Kibre IMC Arba Minch Shilabe Local, Regional, and Mengist Gode International Procurement Plan Logistics Support and Relief Commodities SCF Negele Ferfer Multipurpose Cash Assistance Kelem Multi-Sector Assistance ESTIMATED ACUTE FOOD Nutrition Dolo Ado INSECURITY PHASES Mandera Protection DRC Moyale Psychosocial Support Minimal GOAL Risk Management Policy and Stressed IPC Practice AAH/USA Mercy Corps D.R.C. Crisis UNICEF Shelter and Settlements DRC SCF U.S. In-Kind Food Aid Emergency UGANDA World Vision FAO UNICEF CRS/JEOP Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Famine KENYA GOAL World Vision SOURCE: FEWS NET Food Security IMC CRS/JEOP Refugee Camp Outlook, February - May 2020 Source: UNHCR, August 2018. -

Ethiopia Wind Resources

WIND RESOURCE Ethiopia R e PROPOSED EXISTING d ERITREA HYDRO POWER PLANTS (HEEP) S e a REPUBLIC OF ICS DIESEL POWER PLANTS Humera To Eritrea GAS POWER PLANTS (BIOMASS) Adwa Adigrat YEMEN R Enda Wukro Mesobo e GEOTHERMAL POWER PLANTS SUDAN Silassie Mekele MESSOBO WIND PARK BIOMASS-2 d TEKEZE III WIND POWER PLANTS (Welkayit) ASHEGODA WIND PARK TEKEZE I 500 kV TRANSMISSION LINES Metema Dabat 400 kV TRANSMISSION LINES Maychew Mehoni Substation Sekota S Gonder Alamata e 230 kV TRANSMISSION LINES TENDAHO Lake GEOTHERMAL a 132 kV TRANSMISSION LINES Nefas Tana Wereta Lalibela n Mewcha Decioto Ade 66 kV TRANSMISSION LINES BIOMASS-1 Weldiya DJIBOUTI of Adigrat (Grand Renaissance) BELES Bahir Dar Gashen lf Semera Gu Humera 45 kV TRANSMISSION LINES TIS ABAY I Asayita GRAND RENAISSANCE Dangla TIS ABAY II Axum Source: Ethiopian Power System Expansion Master Plan Study, EEPC 2014 Dessie Combolcha-II Pawe Aksta Mota Combolcha-I Kemise Finote Selam Bitchena UPPER Debre MENDAIA BECO ABO CHEMOGA YEDA II Markos CHEMOGA YEDA I Adigala Asosa AYSHA WIND PARK Alem Ketema Shoa Robit Gebre Fitche-1 DEBRE BERHAN AMERTO ALELTU Mendi Guracha WIND WEPP MU DIESEL Mekele NESHE Debre Hurso BIOMASS-4 Gida Ayana Amibara Fitche-2 Berhan Nuraera DIRE DAWA III (Dedessa) FINCHAA DOFAN Dire Dawa Finchaa II Muger Chancho Akaki Jijiga Dukem I & II Harer To Somalia KALITI DIESEL Sululta Yesu Factory Gimbi Dedessa Debre DIRE DAWA Babile SOMALIA Nekemte Gehedo Addis Zeit-I, -II& -III Awash Asebe Guder Metehara DIESEL Alem Teferi 40MW BIOMASS-3 SCS SOR I WERABESA Woliso Bedessa HARAR I & III (Omo) Gedja Alemaya SCS SOR II GEBA I Buno AWASH Wolkite Geda Wonji 7 KILO ALEMAYA DIESEL Bedele KOKA Chelenko HALELE AWASH II To ADAMA I & II Degeh Bur Aware GEBA II TULLU MOYE Fik South Sudan Butajira AWASH III (1st phase) Gambela Gore BARO I Asela Domo Gonder BARO II G.