Supporting Inclusive Rural Transformation in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Shambel Meressa Advisor

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project By: Shambel Meressa Advisor: Girmay Kahssay (Dr.) A Thesis submitted to the school of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project Shambel Meressa A Thesis Submitted to The School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Shambel Meressa, entitled: “Assessment of potential causes of construction delay in tunnels; a case study at Awash-Weldiya railway project” and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences (Railway Civil Engineering) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Approved by the Examining Committee: Internal Examiner ___________________________ Signature ___________ Date ___________ External Examiner _________________________ Signature____________ Date ____________ Advisor __________________________________ Signature ___________ Date ____________ _____________________________________________________ School or Center Chair Person Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash- Weldiya Railway Project Declaration I declare that this thesis entitled “Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway Project” is my original work. -

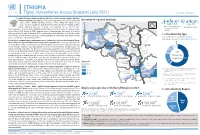

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

Inequality and Stagnation in Ethiopian Agriculture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs Too Much Inequality or Too Little? Inequality and Stagnation in Ethiopian Agriculture Stephen Devereux, Amdissa Teshome and Rachel Sabates-Wheeler * The agricultural sector remains our Achilles heel Following the “creeping coup” that overthrew and source of vulnerability … Nonetheless, we Emperor Haile Selassie during the 1974 famine, remain convinced that agricultural based the Derg implemented a radical agrarian development remains the only source of hope transformation based on redistribution of land. for Ethiopia. (Prime Minister Meles Zenawi 2000) Between 1976 and 1991, all rain-fed farmland in highland Ethiopia was confiscated and redistributed, 1 Introduction after adjusting for soil quality and family size, among A powerful strand of thinking about the causes of all rural households. This land reform was motivated long-term agricultural stagnation in Ethiopia defines not only by the Derg’s Marxist egalitarian ideology, the problem in terms of inequality. Indeed, it is but by its conviction that feudal relations in possible to interpret most Ethiopian agricultural agriculture had exposed millions of highland policy initiatives of the past three decades in terms Ethiopians to intolerable levels of poverty and of divergent views on the extent and consequences vulnerability. Redistribution therefore had both of rural inequality. This article investigates the equity and efficiency objectives. It was implemented hypothesis that (too little rather than too much) as a mechanism not just for breaking the power of inequality has contributed to agriculture’s under- the landlords, but also for eradicating historically performance, and considers the implications for entrenched inequalities in control over land, with policy in terms of four alternative pathways for the aim of achieving sustainable increases in Ethiopian agriculture. -

Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST in ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE

Mekelle Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST IN ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE December 2012 Millennium Cities Initiative, The Earth Institute Columbia University New York, 2012 DISCLAIMER This publication is for informational This publication does not constitute an purposes only and is meant to be purely offer, solicitation, or recommendation for educational. While our objective is to the sale or purchase of any security, provide useful, general information, product, or service. Information, opinions the Millennium Cities Initiative and other and views contained in this publication participants to this publication make no should not be treated as investment, representations or assurances as to the tax or legal advice. Before making any accuracy, completeness, or timeliness decision or taking any action, you should of the information. The information is consult a professional advisor who has provided without warranty of any kind, been informed of all facts relevant to express or implied. your particular circumstances. Invest in Ethiopia: Focus Mekelle © Columbia University, 2012. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. ii PREFACE Ethiopia, along with 189 other countries, The challenges that potential investors adopted the Millennium Declaration in would face are described along with the 2000, which set out the millennium devel- opportunities they may be missing if they opment goals (MDGs) to be achieved by ignore Mekelle. 2015. The MDG process is spearheaded in Ethiopia by the Ministry of Finance and The Guide is intended to make Mekelle Economic Development. and what Mekelle has to offer better known to investors worldwide. Although This Guide is part of the Millennium effort we have had the foreign investor primarily and was prepared by the Millennium Cities in mind, we believe that the Guide will be Initiative (MCI), which is an initiative of of use to domestic investors in Ethiopia as The Earth Institute at Columbia University, well. -

Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia

“ Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia and Agriculture Food Paul Dorosh and Shahidur Rashid Editors Dorosh • PROGRESS AND Rashid Food POLICY CHALLENGES Editors and Agriculture in Ethiopia Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia This book is published by the University of Pennsylvania Press (UPP) on behalf of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) as part of a joint-publication series. Books in the series pre- sent research on food security and economic development with the aim of reducing poverty and eliminating hunger and malnutrition in developing nations. They are the product of peer-reviewed IFPRI research and are selected by mutual agreement between the parties for publication under the joint IFPRI-UPP imprint. Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia Progress and Policy Challenges EDITED BY PAUL A. DOROSH AND SHAHIDUR RASHID Published for the International Food Policy Research Institute University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia Copyright © 2012 International Food Policy Research Institute All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 www.upenn.edu/pennpress Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP DATA TO COME Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables ix List of Boxes xv Foreword xvii Acknowledgments xix Acronyms and Abbreviations xxiii Glossary xxvii 1 Introduction 1 PAUL DOROSH AND SHAHIDUR RASHID PART I Overview and Analysis of Ethiopia’s Food Economy 2 Ethiopian Agriculture: A Dynamic Geographic Perspective 21 JORDAN CHAMBERLIN AND EMILY SCHMIDT 3 Crop Production in Ethiopia: Regional Patterns and Trends 53 ALEMAYEHU SEYOUM TAFFESSE, PAUL DOROSH, AND SINAFIKEH ASRAT GEMESSA 4 Seed, Fertilizer, and Agricultural Extension in Ethiopia 84 DAVID J. -

Famine and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia By: Joachim Von Braun and Tolulope Olofinbiyi

Famine and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia By: Joachim von Braun and Tolulope Olofinbiyi CASE STUDY #7-4 OF THE PROGRAM: "FOOD POLICY FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT IN THE GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEM" 2007 Edited by: Per Pinstrup-Andersen ([email protected]) and Fuzhi Cheng Cornell University In collaboration with: Soren E. Frandsen, FOI, University of Copenhagen Arie Kuyvenhoven, Wageningen University Joachim von Braun, International Food Policy Research Institute Executive Summary Ethiopia, the second most populous country in macroeconomic policies. Second, market Sub-Saharan Africa, is home to about 75 million integration and price stabilization must be in place people. The country has a tropical monsoon for individual projects to function effectively. The climate characterized by wide topographic-induced question of policy and program choice and variations. With rainfall highly erratic, Ethiopia is sequencing arise in determining the optimal usually at a high risk for droughts as well as program mix for mitigating and preventing famine. intraseasonal dry spells. The majority of the But how is such a program mix determined under population depends on agriculture as the primary resource and time constraints? source of livelihood, and the sector is dominated by smallholder agriculture. These small farmers rely Your assignment is to recommend a set of short- on traditional technologies and produce primarily and long-term policies and programs to improve for consumption. food security in Ethiopia that will be compatible with available government resources and reductions Famine vulnerability is high in Ethiopia. With the of Ethiopia's dependence on foreign food aid. rapid population growth of the past two decades, per capita food grain production has declined. -

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility Africa Program Working Paper Series Gilbert M. Khadiagala OCTOBER 2008 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: Elderly women receive ABOUT THE AUTHOR emergency food aid, Agok, Sudan, May 21, 2008. ©UN Photo/Tim GILBERT KHADIAGALA is Jan Smuts Professor of McKulka. International Relations and Head of Department, The views expressed in this paper University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South represent those of the author and Africa. He is the co-author with Ruth Iyob of Sudan: The not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Elusive Quest for Peace (Lynne Rienner 2006) and the welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit editor of Security Dynamics in Africa’s Great Lakes of a well-informed debate on critical Region (Lynne Rienner 2006). policies and issues in international affairs. Africa Program Staff ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS John L. Hirsch, Senior Adviser IPI owes a great debt of thanks to the generous contrib- Mashood Issaka, Senior Program Officer utors to the Africa Program. Their support reflects a widespread demand for innovative thinking on practical IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor solutions to continental challenges. In particular, IPI and Ellie B. Hearne, Publications Officer the Africa Program are grateful to the government of the Netherlands. In addition we would like to thank the Kofi © by International Peace Institute, 2008 Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, which All Rights Reserved co-hosted an authors' workshop for this working paper series in Accra, Ghana on April 11-12, 2008. www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen . i Introduction. 1 Key Challenges . -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

The Role of Community Radio for Integrated and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia: a Critical Review on the Holistic Approach D

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 10 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0260.v1 The Role of Community Radio for Integrated and Sustainable Development in Ethiopia: A Critical Review on the Holistic Approach Destaw Bayable Yemer Guna Tana Integrated Field Research & Development Center, Debre Tabor University, Ethiopia Email: [email protected] Abstract Community radios play a paramount role in the development of the community. Community radio stations have been highly engaged in addressing social, economic, cultural, educational, health, environmental, sanitation, and disaster issues effectively and strategically using local languages in context. Community radios are also used to express, and share indigenous views, thoughts, ideas, problems, and perspectives of local people. The purpose of this analysis is to explore the role of community radio for integrated and sustainable development in Ethiopia. It used a systematic narrative review. Nine research works and five assessments report were selected purposively and analyzed in a quantitative approach. Currently, in Ethiopia, there are 50 community radio stations that received broadcast licenses from Ethiopian Broadcast Authority with four types of licensing and broadcasting in 29 local languages. Community radio helps the community to identify their common goals, create holistic plans, monitor the progress of their developmental activities, and guide on sustainable development. It contributes to integrated and sustainable development in a collaborative and creative process that cultivates the social, economic, and political conditions needed for the community to succeed which aimed to improve and sustain the livelihoods of the community. However, the media can’t achieve its target goal to support the development activities and bring holistic development of the community. -

Debre Markos-Gondar Road

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ethiopian Roads Authority , / International Development Association # I VoL.5 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS OF THE FIVE Public Disclosure Authorized ROADS SELECTED FOR REHABILITATION AND/OR UPGRADING DEBRE MARKOS-GONDAR ROAD # J + & .~~~~~~~~i-.. v<,,. A.. Public Disclosure Authorized -r~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ - -':. a _- ..: r. -. * .. _, f_ £ *.. "''" Public Disclosure Authorized Final Report October 1997 [rJ PLANCENTERLTD Public Disclosure Authorized FYi Opastinsilta6, FIN-00520HELSINKI, FINLAND * LJ Phone+358 9 15641, Fax+358 9 145 150 EA Report for the Debre Markos-Gondar Road Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................... i ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................... iv GENERALMAP OF THE AREA ........................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................... vi I. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Location of the StudyArea. 1 1.3 Objectiveof the Study. 1 1.4 Approachand Methodologyof the Study. 2 1.5 Contentsof the Report. 3 2. POLICY,LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONALFRAMEWORK ....... 4 2.1 Policy Framework..Framewor 4 2.2 Legal Framework..Framewor 6 2.3 InstitutionalFramework. .Framewor 8 2.4 Resettlement and Compensation .12 2.5 Public Consultation 15 3. DESCRIPTIONOF THE PROPOSEDROAD PROJECT........... 16 4. BASELINEDATA ............. ........................... 18 4.1 Descriptionof the Road.18 4.2 Physical Environment nvironmt. 20 4.2.1 Climate and hydrology ................. 20 4.2.2 Physiography ............ ....... 21 4.2.3 Topography and hydrography ............ 21 4.2.4 Geology ....... ............ 21 4.2.5 Soils and geomorphology ................ 21 4.3 BiologicalEnvironment......................... 22 4.3.1 Land use and land cover .22 4.3.2 Flora .22 4.3.3 Fauna .22 4.4 Human and Social Environent .23 4.4.1 Characteristics of the population living by/alongthe road .....................