Reconsidering the Theoretical/Practical Divide: the Philosophy of Nishida Kitarō

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goethe, the Japanese National Identity Through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989

Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik pen Jahrgang LI – Heft 1 | Peter Lang, Bern | S. 57–100 Goethe, the Japanese National Identity through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989 By Stefan Keppler-Tasaki and Seiko Tasaki, Tokyo Dedicated to A . Charles Muller on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Tokyo This is a study of the alleged “singular reception career”1 that Goethe experi- enced in Japan from 1889 to 1989, i. e., from the first translation of theMi gnon song to the last issues of the Neo Faust manga series . In its path, we will high- light six areas of discourse which concern the most prominent historical figures resp. figurations involved here: (1) the distinct academic schools of thought aligned with the topic “Goethe in Japan” since Kimura Kinji 木村謹治, (2) the tentative Japanification of Goethe by Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn, (3) the recognition of the (un-)German classical writer in the circle of the Japanese national author Mori Ōgai 森鴎外, as well as Goethe’s rich resonances in (4) Japanese suicide ideals since the early days of Wertherism (Ueruteru-zumu ウェル テルヅム), (5) the Zen Buddhist theories of Nishida Kitarō 西田幾多郎 and D . T . Suzuki 鈴木大拙, and lastly (6) works of popular culture by Kurosawa Akira 黒澤明 and Tezuka Osamu 手塚治虫 . Critical appraisal of these source materials supports the thesis that the polite violence and interesting deceits of the discursive history of “Goethe, the Japanese” can mostly be traced back, other than to a form of speech in German-Japanese cultural diplomacy, to internal questions of Japanese national identity . -

Hagiwara Sakutarô, Buddhist Realism, and the Establishment of Japanese Modern Poetry

HAGIWARA SAKUTARÔ, BUDDHIST REALISM, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF JAPANESE MODERN POETRY Roberto Pinheiro Machado1 Resumo: Este artigo aborda a obra do poeta Hagiwara Sakutarô (1886-1942) a partir de uma perspectiva comparativa que engaja filosofia e literatura. A dimensão filosófica da poesia de Sakutarô é analisada por meio de uma leitura intertextual entre a obra do poeta japonês e a epistemologia budista presente nos textos em sânscrito dos filósofos Dignāga and Dharmakīrti (século V). Essa análise comparativa é efetuada sob a perspectiva da influência do naturalismo europeu no surgimento da poesia japonesa moderna. Demonstrando a possibilidade de um realismo budista que compartilha importantes características estéticas com o naturalismo, o artigo enfatiza a dimensão budista da poesia de Sakutarô, a qual se desvela apesar da rejeição ao budismo operada pelo próprio poeta como passo necessário para o estabelecimento da modernidade nas letras japonesas. Palavras-chave: Hagiwara Sakutarô, Poesia japonesa, Budismo, Modernidade, Filosofia Abstract: This article approaches the works of poet Hagiwara Sakutarô (1886-1942) from a comparative perspective that engages philosophy and literature. The philosophical dimension of Sakutarô’s poetry is analyzed by means of inter-textual readings that draw on the tradition of Buddhist epistemology and on the texts of logicians Dignāga and Dharmakīrti (5th century). The comparative analysis is considered under the perspective of the influence of Naturalism and the use of description in the emergence of Japanese modern poetry. Pointing to the possibility of a Buddhist realism that shares some common characteristics with Naturalism, the article emphasizes the Buddhist dimension of Sakutarô’s poetry, which appears in spite of the poet’s turn to Western philosophy (notably 1. -

2019-20 Annual Report

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT AND PROGRAM OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES Annual Report 2019-2020 1 COVER: The wooden doors to 202 Jones. Photo taken by Martin Kern. 2 Annual Report 2019-20 Contents Director’s Letter 4 Department and Program News 6 Language Programs 8 Undergraduates 11 Graduate Students 14 Faculty 18 Events 24 Summer Programs 26 Affiliated Programs 29 Libraries & Museum 34 3 Director’s Letter, 2019-20 In normal years, the Director’s Letter is a retrospective of the year in East Asian Studies—but where to begin? Annual disasters and upheavals are standard topics in traditional East Asian chronicles. By June of 2020 (a gengzi 庚子 year), we had already lived through more than our share: the coronavirus pandemic, severe economic downturn, government inaction and prevarication, Princeton’s shift to online teaching, dislocation of undergraduate and graduate life, shuttering of libraries and labs, disruption to travel, study, and research for students, staff, and faculty, the brutal murder of George Floyd, and the international renaissance of the Black Lives Matter movement. invigorate campus intellectual life, completing book This spring semester, the usual hum of summer manuscripts, or starting new projects. The heaviest burden, programming and plans for next academic year grew no doubt, fell on our language instructors. The faculty quiet, and many EAS projects were cancelled, postponed, in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean innovated non-stop to shifted online, or put on hold. As this Annual Report goes insure that, in the era of Zoom, students would remain fully to press, plans for undergraduate residence on campus engaged in all four language skills of speaking, listening, and the format for classes in fall of 2020 are still being reading, and writing. -

'What Is Japanese Philosophy'?

Introduction: ‘What is Japanese Philosophy’? 459 Introduction: ‘What is Japanese Philosophy’? Raji C. Steineck and Elena Louisa Lange Remarks on the History of a Problem Until very recently, a first inquiry about ‘Japanese Philosophy’ could end up right in wonderland. Depending on which book or expert one turned to for general orientation, one would either learn that a) ‘Philosophy’ has never existed in Japan;1 b) ‘Philosophy’ was evident in Japan from the earliest written sources;2 or c) ‘Japanese Philosophy’ started with Nishida Kitarō’s Study of the Good (1911).3 To make things even more mind-boggling, experts and books upholding proposition b) – philosophical thought is evident in Japan from the earliest written sources – would either assert that it was b’) essentially the same as in the West, or b’’) essentially different from Western, and even from Indian and Chinese philosophy. The publication of a monumental sourcebook in Japanese Philosophy which contains materials from the 8th to the 20th century,4 and the introduction of pertinent articles in standard philosophical encyclopaedias such as the Routledge and the Stanford Encyclopaedias of Philosophy have changed the situation somewhat in the Western world, giving pre-eminence to variants of position b). But position a) is still upheld by many, 1 The locus classicus is Nakae Chōmin’s statement: ‘Since olden times to this day there has been no philosophy in Japan’, quoted recently eg. in Clinton, ‘“Philosophy” or “Religion”?’, p. 75. Godart adds: ‘This view, that there is no such thing as Japanese thought before 1868 which can be labeled “philosophy”, has become prevalent in Japan. -

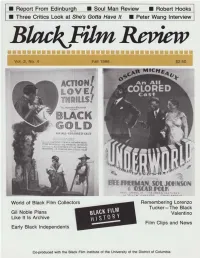

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Following the Argument Where It Leads

Following The Argument Where It Leads Thomas Kelly Princeton University [email protected] Abstract: Throughout the history of western philosophy, the Socratic injunction to ‘follow the argument where it leads’ has exerted a powerful attraction. But what is it, exactly, to follow the argument where it leads? I explore this intellectual ideal and offer a modest proposal as to how we should understand it. On my proposal, following the argument where it leaves involves a kind of modalized reasonableness. I then consider the relationship between the ideal and common sense or 'Moorean' responses to revisionary philosophical theorizing. 1. Introduction Bertrand Russell devoted the thirteenth chapter of his History of Western Philosophy to the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. He concluded his discussion with a rather unflattering assessment: There is little of the true philosophic spirit in Aquinas. He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better: If he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times (1945: 463). The extent to which this is a fair assessment of Aquinas is controversial.1 My purpose in what follows, however, is not to defend Aquinas; nor is it to substantiate the charges that Russell brings against him. -

(LACMA) Hosted Its Ninth Annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, Honoring Artist Betye Saar and Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón

(Los Angeles, November 3, 2019)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its ninth annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, honoring artist Betye Saar and filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. Co-chaired by LACMA trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the evening brought together more than 800 distinguished guests from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries, among others. This year’s gala raised more than $4.6 million, with proceeds supporting LACMA’s film initiatives and future exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming. The 2019 Art+Film Gala was made possible through Gucci’s longstanding and generous partnership. Additional support for the gala was provided by Audi. Eva Chow, co-chair of the Art+Film Gala, said, “I’m so happy that we have outdone ourselves again with the most successful Art+Film Gala yet. It was such a joy to celebrate Betye Saar and Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible creativity and passion, while supporting LACMA’s art and film initiatives. I couldn’t be more grateful to Alessandro Michele, Marco Bizzarri, and everyone at Gucci—our invaluable partner since the first Art+Film Gala—and to Anderson .Paak and The Free Nationals for making this evening one to remember.” “I’m deeply grateful to our returning co-chairs Eva Chow and Leonardo DiCaprio for helping us set another Art+Film Gala record,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “We honored two incredibly powerful artistic voices this year. Betye Saar has helped define the genre of Assemblage art for nearly seven decades, and recognition of her as one of the most important and influential artists working today is long overdue. -

Patterns in Spiritual Awakening: a Study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2017 Patterns in spiritual awakening: A study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot Lucy Shafik Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Shafik, L. (2017).Patterns in spiritual awakening: A study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1366 MLA Citation Shafik, ucyL . Patterns in spiritual awakening: A study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1366 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Patterns in Spiritual Awakening: A Study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot A Thesis Submitted to The Department of English and Comparative Literature In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Lucy Shafik Under the supervision of Dr. William Melaney May 2017 The American University in Cairo Patterns in Spiritual Awakening: A Study of Augustine, Coleridge and Eliot A Thesis Submitted by Lucy Shafik To the Department of English and Comparative Literature May 2017 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts Has been approved by Dr. William Melaney Thesis Committee Advisor____________________________________________ Affiliation_________________________________________________________ Dr. -

Philosophy 1

Philosophy 1 PHILOSOPHY VISITING FACULTY Doing philosophy means reasoning about questions that are of basic importance to the human experience—questions like, What is a good life? What is reality? Aileen Baek How are knowledge and understanding possible? What should we believe? BA, Yonsei University; MA, Yonsei University; PHD, Yonsei University What norms should govern our societies, our relationships, and our activities? Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy; Visiting Scholar in Philosophy Philosophers critically analyze ideas and practices that often are assumed without reflection. Wesleyan’s philosophy faculty draws on multiple traditions of Alessandra Buccella inquiry, offering a wide variety of perspectives and methods for addressing these BA, Universitagrave; degli Studi di Milano; MA, Universitagrave; degli Studi di questions. Milano; MA, Universidad de Barcelona; PHD, University of Pittsburgh Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy William Paris BA, Susquehanna University; MA, New York University; PHD, Pennsylvania State FACULTY University Stephen Angle Frank B. Weeks Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy BA, Yale University; PHD, University of Michigan Mansfield Freeman Professor of East Asian Studies; Professor of Philosophy; Director, Center for Global Studies; Professor, East Asian Studies EMERITI Lori Gruen Brian C. Fay BA, University of Colorado Boulder; PHD, University of Colorado Boulder BA, Loyola Marymount University; DPHIL, Oxford University; MA, Oxford William Griffin Professor of Philosophy; Professor -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

An Analysis of Sound and Music in the Shining and Bridget Jones' Diary

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 2019 The oundS s Behind the Scenes: An Analysis of Sound and Music in The hininS g and Bridget Jones’ Diary Abby Fox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Communication Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Running head: THE SOUNDS BEHIND THE SCENES The Sounds Behind the Scenes: An Analysis of Sound and Music in The Shining and Bridget Jones’ Diary Abby Fox Communication Studies Advisor: Satish Kolluri December 2018 THE SOUNDS BEHIND THE SCENES 2 Abstract Although often subtle, music and sounds have been an integral part of the motion picture experience since the days of silent films. When used effectively, sounds in film can create emotion, give meaning to a character’s actions or feelings, act as a cue to direct viewers’ attention to certain characters or settings, and help to enhance the overall storytelling. Sound essentially acts as a guide for the audience as it evokes certain emotions and reactions to accompany the narrative unfolding on-screen. The aim of this thesis is to focus on two specific films of contrasting genres and explore how the music and sounds help to establish the genres of the given films, as well as note any commonalities in which the films follow similar aural patterns. By conducting a content analysis and theoretical review, this study situates the sound use among affect theory, aesthetics and psychoanalysis, which are all highly relevant to the reception of music and sound in film. Findings consist of analyses of notable instances of sound use in both films that concentrate on the tropes of juxtaposition, contradiction, repetition and leitmotifs, and results indicate that there are actually similar approaches to using sound and music in both films, despite them falling under two vastly different genres. -

On the Risks of Approaching a Philosophical Movement Outside of Philosophy

doi: 10.12957/childphilo.2017.29954 on the risks of approaching a philosophical movement outside of philosophy walter omar kohan1 state university of rio de janeiro, brasil david knowles kennedy2 montclair state university, united states of america abstract Biesta states at the beginning of his intervention that he will speak “as an educationalist,” outside not only of “philosophical work with children” but “outside of philosophy.” What are the implications of these assumptions in terms of “what is philosophy?” and “what is education?” Can we really speak about “philosophical work with children” outside philosophy? What are the consequences of taking this position? From this initial questioning, in this response some other questions are offered to Biesta’s presentation: is philosophical work with children about asking better questions or asking questions better, as he states in his presentation? Finally, risks of philosophy for children as presented by Biesta are examined: a) of being reduced to critical thinking, i.e., “to keeping a clear head”; b) that, even extended to creative and caring thinking, it could “stay in the head” and “not touch the soul”; c) that through the building of communities of inquiry in the classroom, we establish a kind of artificial setting where “we end up living in an idea about the world rather than the world”. Our response ends with a last reference to Biesta’s approach to education in terms of “growing” and existence in terms of a “grown-up way” of being in the world. keywords: philosophy with children; critical thinking; risks; dogmatic image of thinking sobre os riscos de se abordar um movimento filosófico fora da filosofia resumo Biesta declara no começo de sua intervenção que ele falará “como um experto educacional” de fora não somente do “trabalho filosófico com crianças” mas também “de fora da filosofia”.