An Analysis of Sound and Music in the Shining and Bridget Jones' Diary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2017 yS mposium Apr 12th, 3:00 PM - 3:30 PM Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M. DePree Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons DePree, Kelsey M., "Cue the Music: Music in Movies" (2017). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2017/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Music We Watch Kelsey De Pree Music History II April 5, 2017 Music is universal. It is present from the beginning of history appearing in all cultures, nations, economic classes, and styles. Music in America is heard on radios, in cars, on phones, and in stores. Television commercials feature jingles so viewers can remember the products; radio ads sing phone numbers so that listeners can recall them. In schools, students sing songs to learn subjects like math, history, and English, and also to learn about general knowledge like the days of the week, months of the year, and presidents of the United States. With the amount of music that is available, it is not surprising that music has also made its way into movie theatres and has become one of the primary agents for conveying emotion and plot during a cinematic production. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

The Use of Music in the Cinematic Experience

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2019 The seU of Music in the Cinematic Experience Sarah Schulte Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Schulte, Sarah, "The sU e of Music in the Cinematic Experience" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 780. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/780 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND AND EMOTION: THE USE OF MUSIC IN THE CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky Univeristy By Sarah M. Schulte May 2019 ***** CE/T Committee: Professor Matthew Herman, Advisor Professor Ted Hovet Ms. Siera Bramschreiber Copyright by Sarah M. Schulte 2019 Dedicated to my family and friends ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the help and support of so many people. I am incredibly grateful to my faculty advisor, Dr. Matthew Herman. Without your wisdom on the intricacies of composition and your constant encouragement, this project would not have been possible. To Dr. Ted Hovet, thank you for believing in this project from the start. I could not have done it without your reassurance and guidance. -

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

Film Scoring

Film Scoring Film scoring is the act of creating background music to accompany a film. The film scoring process has a number of steps and contributors. Below are just a few of the jobs necessary to creating a film score. Composing the Score A film composer scores music to accompany a motion picture for film or television. This could be of any genre and include any instrumentation. Film scores consist of music composed specifically for the movie or TV show, and should not be confused with a movie soundtrack, which is a collection of pre-existing songs used in a movie or show. Editing the Music A music editor is responsible for mixing and synchronizing the music with the film and mixing the music with the film soundtrack. The music editor must be have a good ear for musical balance as well as an awareness of how music can make or break a dramatic scene; all combined with knowledge of the special technology used in synchronizing music tracks to film or tape. Programming/Sequencing The programmer utilizes music sequencing software and sometimes notation software to produce MIDI keyboard/synthesizer tracks for inclusion in the film score. Other times, a programmer will sequence a piece of music or a composition by this means, which will allow the composer and music editor an opportunity to hear the composition before it reaches the scoring stage. Orchestrating The film music orchestrator is responsible for writing scores for an orchestra, band, choral group, individual instrumentalist(s), or vocalist(s). Also, an orchestrator transposes music from one instrument or voice to another in order to accommodate a particular music instrument, musician, or group. -

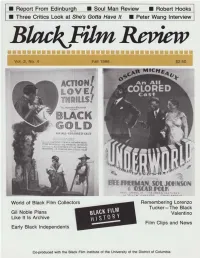

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

(LACMA) Hosted Its Ninth Annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, Honoring Artist Betye Saar and Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón

(Los Angeles, November 3, 2019)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its ninth annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, honoring artist Betye Saar and filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. Co-chaired by LACMA trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the evening brought together more than 800 distinguished guests from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries, among others. This year’s gala raised more than $4.6 million, with proceeds supporting LACMA’s film initiatives and future exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming. The 2019 Art+Film Gala was made possible through Gucci’s longstanding and generous partnership. Additional support for the gala was provided by Audi. Eva Chow, co-chair of the Art+Film Gala, said, “I’m so happy that we have outdone ourselves again with the most successful Art+Film Gala yet. It was such a joy to celebrate Betye Saar and Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible creativity and passion, while supporting LACMA’s art and film initiatives. I couldn’t be more grateful to Alessandro Michele, Marco Bizzarri, and everyone at Gucci—our invaluable partner since the first Art+Film Gala—and to Anderson .Paak and The Free Nationals for making this evening one to remember.” “I’m deeply grateful to our returning co-chairs Eva Chow and Leonardo DiCaprio for helping us set another Art+Film Gala record,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “We honored two incredibly powerful artistic voices this year. Betye Saar has helped define the genre of Assemblage art for nearly seven decades, and recognition of her as one of the most important and influential artists working today is long overdue. -

Reconsidering the Theoretical/Practical Divide: the Philosophy of Nishida Kitarō

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Reconsidering The Theoretical/Practical Divide: The Philosophy Of Nishida Kitarō Lockland Vance Tyler University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Tyler, Lockland Vance, "Reconsidering The Theoretical/Practical Divide: The Philosophy Of Nishida Kitarō" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 752. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/752 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECONSIDERING THE THEORETICAL/PRACTICAL DIVIDE: THE PHILOSOPHY OF NISHIDA KITARŌ A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Philosophy University of Mississippi by LOCKLAND V. TYLER APRIL 2013 Copyright Lockland V. Tyler 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Over the years professional philosophy has undergone a number of significant changes. One of these changes corresponds to an increased emphasis on objectivity among philosophers. In light of new discoveries in logic and science, contemporary analytic philosophy seeks to establish the most objective methods and answers possible to advance philosophical progress in an unambiguous way. By doing so, we are able to more precisely analyze concepts, but the increased emphasis on precision has also been accompanied by some negative consequences. These consequences, unfortunately, are much larger and problematic than many may even realize. What we have eventually arrived in at in contemporary Anglo-American analytic philosophy is a complete repression of humanistic concerns. -

Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’S the Hinins G Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected]

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-22-2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Bethany, "“Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g" (2015). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 30. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/30 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Miller 1 Bethany Miller Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 8 April 2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Stanley Kubrick’s horror masterpiece The Shining has confounded and fascinated viewers for decades. Perhaps its most mystifying element is its final zoom, which gradually falls on a picture of Jack Torrance beaming in front of a crowd with the caption “July 4 th Ball, Overlook Hotel, 1921.” While Bill Blakemore and others examine the film as a critique of violence in American history, no scholar has thoroughly established the connection between July 4 th, 1921, Jack Torrance, and the rest of the film. -

Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2020 Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises Deirdre M. Flood The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3574 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEGEND HAS IT: TRACKING THE RESEARCH TROPE IN SUPERNATURAL HORROR FILM FRANCHISES by DEIRDRE FLOOD A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 DEIRDRE FLOOD All Rights Reserved ii Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Leah Anderst Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood Advisor: Leah Anderst This study will analyze how information about monsters is conveyed in three horror franchises: Poltergeist (1982-2015), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-2010), and The Ring (2002- 2018). My analysis centers on the changing role of libraries and research, and how this affects the ways that monsters are portrayed differently across the time periods represented in these films. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful.