DRAFT-FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Transportation Research Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE 1 PROFILES W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRLINES SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS Lufthansa 1 Lufthansa 1,739,886 Ryanair 2 Ryanair 1,604,799 Air France 3 Air France 1,329,819 easyJet Britis 4 easyJet 1,200,528 Airways 5 British Airways 1,025,222 SAS 6 SAS 703,817 airberlin KLM Royal 7 airberlin 609,008 Dutch Airlines 8 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 571,584 Iberia 9 Iberia 534,125 Other Western 10 Norwegian Air Shuttle 494,828 W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRPORTS SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 Europe R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS 1 London Heathrow Airport 1,774,606 2 Paris Charles De Gaulle Airport 1,421,231 Outlook 3 Frankfurt Airport 1,394,143 4 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol 1,052,624 5 Madrid Barajas Airport 1,016,791 HE EUROPEAN AIRLINE MARKET 6 Munich Airport 1,007,000 HAS A NUMBER OF DIVIDING LINES. 7 Rome Fiumicino Airport 812,178 There is little growth on routes within the 8 Barcelona El Prat Airport 768,004 continent, but steady growth on long-haul. MostT of the growth within Europe goes to low-cost 9 Paris Orly Field 683,097 carriers, while the major legacy groups restructure 10 London Gatwick Airport 622,909 their short/medium-haul activities. The big Western countries see little or negative traffic growth, while the East enjoys a growth spurt ... ... On the other hand, the big Western airline groups continue to lead consolidation, while many in the East struggle to survive. -

Wayfinding at Airports

WAYFINDING AT AIRPORTS – a LAirA Project Report - LAirA is financially supported by the European Union’s Interreg Central Europe programme, which is a European cohesion policy programme that encourages cooperation beyond borders. LAirA is a 30-months project (2017-2019), with a total budget of €2.3 million. LAirA PROJECT 2019 © All images courtesy of Transporting Cities Ltd. Printed on recycled paper Print and layout: Airport Regions Conference airportregions.org info@ airportregions.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 5 LAirA Project in a nutshell 5 Executive summary 7 PART 1: WHAT IS WAYFINDING AT AIRPORTS 7 1.1 Airport passenger types 7 1.2 The context of wayfinding at airports 10 1.3 Wayfinding access to public transport around the world 10 1.4 Wayfinding to deliver an exemplary journey through the airport 11 1.4.1 First step: Orientating the passenger 11 1.4.2 Promoting public transport and introducing the iconography 12 1.4.3 Making the association to the transport destination 13 1.4.4 Avoiding the moment of doubt when emerging into the public area 13 1.4.5 Using icons to lead the way through the terminal 15 1.4.6 Providing reassurance along the way 15 1.4.7 Identifying the transport destination 16 1.4.8 Draw a picture for complicated transport connections 17 PART 2: PRINCIPLES OF WAYFINDING 17 2.1 The ideal journey to public transport 17 2.2 Identifying the principles of wayfinding 20 PART 3: WAYFINDING IN LAIRA REGIONS OR FUNCTIONAL URBAN AREAS 20 3.1 LAirA partners and the principles of wayfinding 20 3.2 Partner questionnaire 20 3.3 Analysis of questionnaire responses 22 PART 4: CONCLUSION 22 4.1 Capitalising on transport investment 22 4.2 Wayfinding and access to airports 23 4.3 Conclusion and recommendation INTRODUCTION LAirA project in a nutshell Executive summary LAirA (Landside Airport Accessibility) addresses the This report considers the theme of wayfinding at specific and significant challenge of the multimodal, airports. -

![Contents [Edit] Africa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9562/contents-edit-africa-79562.webp)

Contents [Edit] Africa

Low cost carriers The following is a list of low cost carriers organized by home country. A low-cost carrier or low-cost airline (also known as a no-frills, discount or budget carrier or airline) is an airline that offers generally low fares in exchange for eliminating many traditional passenger services. See the low cost carrier article for more information. Regional airlines, which may compete with low-cost airlines on some routes are listed at the article 'List of regional airlines.' Contents [hide] y 1 Africa y 2 Americas y 3 Asia y 4 Europe y 5 Middle East y 6 Oceania y 7 Defunct low-cost carriers y 8 See also y 9 References [edit] Africa Egypt South Africa y Air Arabia Egypt y Kulula.com y 1Time Kenya y Mango y Velvet Sky y Fly540 Tunisia Nigeria y Karthago Airlines y Aero Contractors Morocco y Jet4you y Air Arabia Maroc [edit] Americas Mexico y Aviacsa y Interjet y VivaAerobus y Volaris Barbados Peru y REDjet (planned) y Peruvian Airlines Brazil United States y Azul Brazilian Airlines y AirTran Airways Domestic y Gol Airlines Routes, Caribbean Routes and y WebJet Linhas Aéreas Mexico Routes (in process of being acquired by Southwest) Canada y Allegiant Air Domestic Routes and International Charter y CanJet (chartered flights y Frontier Airlines Domestic, only) Mexico, and Central America y WestJet Domestic, United Routes [1] States and Caribbean y JetBlue Airways Domestic, Routes Caribbean, and South America Routes Colombia y Southwest Airlines Domestic Routes y Aires y Spirit Airlines Domestic, y EasyFly Caribbean, Central and -

Zum Gutachen

FOLGEUNTERSUCHUNG: HANNOVER AIRPORT EIN ZENTRALER WIRTSCHAFTS- UND STANDORT- FAKTOR FÜR DIE REGION Untersuchung im Auftrag der Flughafen Hannover-Langenhagen GmbH Prof. Dr. Lothar Hübl Dr. Karin Janssen Dipl.-Ök. Bernd Wegener Hannover, aktualisiert im Mai 2019 ANSCHRIFT DER VERFASSER: __________________________________________________________ ISP Eduard Pestel Institut für Systemforschung e.V. Gretchenstr. 7, 30161 Hannover, [email protected] INHALT Seite VORBEMERKUNG WICHTIGE ERGEBNISSE IM ÜBERBLICK I-XIII 1. TENDENZEN UND SPANNUNGSFELDER IM LUFTVERKEHR 1 2. TECHNISCHE AUSSTATTUNG UND VERKEHRSENTWICKLUNG: BESTANDSAUFNAHME 13 2.1 Ausstattung 13 2.2 Direktverbindungen und Fluggastaufkommen 21 2.3 Luftfrachtaufkommen 33 2.4 Luftpostaufkommen 35 2.5 Flugzeugbewegungen 36 3. BEVÖLKERUNGS- UND WIRTSCHAFTSSTRUKTUR DER FLUGHAFENREGION HANNOVER 38 3.1 Ermittlung des Einzugsgebietes 38 3.2 Bevölkerungsstruktur und Bevölkerungsdynamik in der Flughafenregion Hannover 42 3.3 Wirtschaftliche Bedeutung und Wirtschaftsstruktur der Flughafenregion Hannover 45 4. FLUGHAFENREGION IM INTERNATIONALEN WETTBEWERB 55 4.1 Art und Form der außenwirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten niedersächsischer Unternehmen 59 4.2 Warenhandel mit dem Ausland 63 4.3 Dienstleistungsverkehr mit dem Ausland 72 4.4 Direktinvestitionsverflechtungen mit dem Ausland 79 5. HANNOVER AIRPORT ALS STANDORTFAKTOR 85 5.1 Grundsätzliche Überlegungen zur Standortgunst 85 5.2 Wechselwirkungen mit weiteren Standortfaktoren 86 5.3 Relevanz von Standortfaktoren für Unternehmen 88 INHALT Seite 6. -

United States Court of Appeals for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 1 of 12 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued November 8, 2011 Decided January 6, 2012 No. 11-1018 REPUBLIC AIRLINE INC., PETITIONER v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, RESPONDENT On Petition for Review of an Order of the Department of Transportation Christopher T. Handman argued the cause for the petitioner. Robert E. Cohn, Patrick R. Rizzi and Dominic F. Perella were on brief. Timothy H. Goodman, Senior Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, argued the cause for the respondent. Robert B. Nicholson and Finnuala K. Tessier, Attorneys, United States Department of Justice, Paul M. Geier, Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, and Peter J. Plocki, Deputy Assistant General Counsel for Litigation, were on brief. Joy Park, Trial Attorney, United States Department of Transportation, entered an appearance. USCA Case #11-1018 Document #1351383 Filed: 01/06/2012 Page 2 of 12 2 Before: HENDERSON, Circuit Judge, and WILLIAMS and RANDOLPH, Senior Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge HENDERSON. KAREN LECRAFT HENDERSON, Circuit Judge: Republic Airline Inc. (Republic) challenges an order of the Department of Transportation (DOT) withdrawing two Republic “slot exemptions” at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (Reagan National) and reallocating those exemptions to Sun Country Airlines (Sun Country). In both an informal letter to Republic dated November 25, 2009 and its final order, DOT held that Republic’s parent company, Republic Airways Holdings, Inc. (Republic Holdings), engaged in an impermissible slot-exemption transfer with Midwest Airlines, Inc. (Midwest). -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Baggage Report 2011

Baggage Report 2011 Specialists in air transport communications and IT solutions Baggage Report 2011 2 SITA Baggage Report 2011 Baggage Report 2011 Preface It has been a difficult year for all those Nonetheless, the air transport industry related to the cost of getting it back to involved in the air transport industry’s responded remarkably well. It is clear its owner. SITA, as the global operator response to the great logistical that improvements in technology, the of the tracking and tracing service for challenge of making sure that over two increasing deployment of baggage lost baggage continues to play its part, billion passengers’ bags get on the sortation systems and IATA’s Baggage innovating and bringing new improved right planes and are delivered to the Improvement Program are having an baggage management solutions to the right carousels in reasonable time for impact on keeping down the numbers market like BagSmart which we have collection by their owners. of bags mishandled. While there was already tested successfully at London a rise in the absolute number of bags Heathrow with the Star Alliance. It will Airlines, airports and ground handlers mishandled, this had to be expected be widely available in 2011 and is the respond to this task with the minimum in the circumstances. However, the first web-based application in the air of fuss but all were put to a severe test long-term trend shows the industry is transport industry that can warn of last year as passenger volumes rose for driving down overall mishandling rates potential baggage mishandlings the first time in two years and nature as it brings knowledge, experience and before they occur. -

Easy-Peasy Self-Service Bag Tagging About 14 Million Easyjet Passengers Flying in and out of Gatwick Airport Choose to Use the Self-Service Bag-Drop System

Company insight > Routes Company insight > Routes Easy-peasy self-service bag tagging About 14 million easyJet passengers flying in and out of Gatwick Airport choose to use the self-service bag-drop system. Considering that the airline introduced it just two and a half years ago, the uptake has been swift. Thomas Doogan, ground-operations customer experience manager at easyJet, speaks about the shift in passenger behaviour and the role eezeetags is playing in the airline’s innovation. client convenience, intends to raise that to 45% by the end of 2017, and to 70% by the end of 2018. There have been major benefits, not least in efficiency, says Doogan. “The perception of our friendliness by customers has increased by 10% and that is in the top two boxes – people who are ‘very satisfied’ and ‘extremely satisfied’.” As airports seek to streamline passenger flow, self-service facilities offer smoother, stress-free operations for travellers. The customers’ praise is attributable to the ground crew’s new-found freedom. Previously, the crew had to training on how to effectively use. These were comparatively “By really understanding each customer, we found the dedicate time and energy to tagging baggage in addition to complex and, therefore, left to the airline staff to apply. best solution for everyone and, therefore, the best overall interacting with customers. Now, its sole focus is greeting “We cannot expect passengers using a modern bag-drop solution for all travellers.” self-service passengers and being on hand to assist those system to apply a bag tag that was designed 40 years ago and While easyJet can lay claim to the title of kick-starter of in need of help to navigate the new system, which doesn’t meant to be applied by a trained agent,” stresses Vrieling. -

ACI EUROPE AIRPORT BUSINESS, 02.06.17 SAP No

SUMMER ISSUE 2017 Every flight begins a t the airport. Düsseldorf on the hunt for more long-haul connectivity Interview: Thomas Schnalke, CEO Düsseldorf Airport EASA certification Is Cobalt a future blue PLUS the A to Z of interviews countdown chip airline? ADP Ingénierie, Bristol, Edinburgh, Fraport Twin Star, Kraków, Newcastle, The state of play & what to expect Interview with Andrew Madar, CEO Cobalt Sochi and Zagreb For quick arrivals and departures For more information, contact Wendy Barry: Partner with the 800.888.4848 x 1788 or 203.877.4281 x 1788 e-mail: [email protected] #1 franchise*. or visit www.subway.com * #1 In total restaurant count with more locations than any other QSR. Subway® is a Registered Trademark of Subway IP Inc. ©2017 Subway IP Inc. CONTENTS 07 08 10 AUGUSTIN DE AIRPORTS IN THOMAS SCHNALKE, ROMANET, THE NEWS CEO DÜSSELDORF PRESIDENT OF AIRPORT ACI EUROPE A snapshot of stories from around Europe Düsseldorf expanding long-haul Editorial: The strength in unity connections to global economic centres 16 19 20 AIRPORT COMMERCIAL AIRPORT PEOPLE DME LIVE 2.0 & RETAIL CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION Gratien Maire, CEO ADP Ingénierie So you think you can run an airport? Airport Commercial & Retail executives gather in Nice Airports Council International Director: Media & Communications Magazine staff PPS Publications Ltd European Region, Robert O'Meara Rue Montoyer, 10 (box n. 9), Tel: +32 (0)2 552 09 82 Publisher and Editor-in-Chief Paul J. Hogan 3a Gatwick Metro Centre, Balcombe Road, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium Fax: +32 (0)2 -

AIRLINE REQUIREMENTS for DESIGN TENANT DEVELOPMENT GUIDELINES Copyright ©2015 by Denver International Airport

AIRLINE REQUIREMENTS FOR DESIGN TENANT DEVELOPMENT GUIDELINES Copyright ©2015 by Denver International Airport All rights reserved No part of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents The Jeppesen Terminal .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Terminal East and West Sides ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Levels of the Terminal ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Door Numbers ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Hotel and Transit Center ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

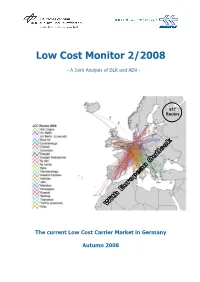

Low Cost Monitor 2/2008

Low Cost Monitor 2/2008 - A Joint Analysis of DLR and ADV - 617 Routes The current Low Cost Carrier Market in Germany Autumn 2008 The current Low Cost Carrier Market in Germany (2008) Since several years the low cost carrier (LCC) market is an essential part of the German air transport market. The Low Cost Monitor, jointly issued by ADV and DLR, twice a year informs on LCC’s essential features and current developments in this market segment, particularly as to the number and relative importance of low cost carriers, their offers including the air fare, and the passenger demand. The offers reflected by the current Monitor are based on one reference week of the summer flight schedule 2008. The passenger traffic indicated relates to the half year total of 2008. Airlines 4 The airlines involved in the Low Cost business, design their flight services quite differently. Due to this inhomogeneity, only a few clear distinctive criteria can be defined, for example low fares and direct sale via the Internet. Thus, in some cases a certain scope of discretion arises when allocating an airline to the LCC-segment. Furthermore, for several airlines amalgamations of business models are seen, which additionally complicate the accurate allocation of airlines to the Low Cost Market. The authors of this Monitor currently classify 23 airlines operating on German airports as low cost carriers. These are in detail (see also Table 1): Aer Lingus (EI) (www.aerlingus.com), Fleet: 33 Aircraft (A320: 27/A321: 6) Air Baltic (BT) (www.airbaltic.com), Fleet: 25 Aircraft -

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18.