The Ballad Book a Selection of the Choicest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letters of Robert Burns 1

The Letters of Robert Burns 1 The Letters of Robert Burns The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Robert Burns, by Robert Burns #3 in our series by Robert Burns Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. The Letters of Robert Burns 2 **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Letters of Robert Burns Author: Robert Burns Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9863] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 25, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr and PG Distributed Proofreaders BURNS'S LETTERS. THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, SELECTED AND ARRANGED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY J. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Social Issues in Ballads and Songs, Edited by Matilda Burden

SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Edited by MATILDA BURDEN Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Social Issues in Ballads and Songs Edited by MATILDA BURDEN STELLENBOSCH KOMMISSION FÜR VOLKSDICHTUNG 2020 Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications Copyright © Matilda Burden and contributors, 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. Peer-review statement All papers have been subject to double-blind review by two referees. Editorial Board for this volume Ingrid Åkesson (Sweden) David Atkinson (England) Cozette Griffin-Kremer (France) Éva Guillorel (France) Sabina Ispas (Romania) Christine James (Wales) Thomas A. McKean (Scotland) Gerald Porter (Finland) Andy Rouse (Hungary) Evelyn Birge Vitz (USA) Online citations accessed and verified 25 September 2020. Contents xxx Introduction 1 Matilda Burden Beaten or Burned at the Stake: Structural, Gendered, and 4 Honour-Related Violence in Ballads Ingrid Åkesson The Social Dilemmas of ‘Daantjie Okso’: Texture, Text, and 21 Context Matilda Burden ‘Tlačanova voliča’ (‘The Peasant’s Oxen’): A Social and 34 Speciesist Ballad Marjetka Golež Kaučič From Textual to Cultural Meaning: ‘Tjanne’/‘Barbel’ in 51 Contextual Perspective Isabelle Peere Sin, Slaughter, and Sexuality: Clamour against Women Child- 87 Murderers by Irish Singers of ‘The Cruel Mother’ Gerald Porter Separation and Loss: An Attachment Theory Approach to 100 Emotions in Three Traditional French Chansons Evelyn Birge Vitz ‘Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jivin’ too’: 116 The Blues-Like Sentiment of Hip Hop Ballads Salim Washington Introduction Matilda Burden As the 43rd International Ballad Conference of the Kommission für Volksdichtung was the very first one ever to be held in the Southern Hemisphere, an opportunity arose to play with the letter ‘S’ in the conference theme. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

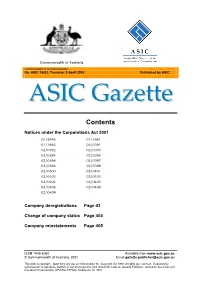

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002

= = `çããçåïÉ~äíÜ=çÑ=^ìëíê~äá~= = Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002 Published by ASIC ^^ppff``==dd~~òòÉÉííííÉÉ== Contents Notices under the Corporations Act 2001 00/2496 01/1681 01/1682 02/0391 02/0392 02/0393 02/0394 02/0395 02/0396 02/0397 02/0398 02/0399 02/0400 02/0401 02/0402 02/0403 02/0404 02/0405 02/0406 02/0408 02/0409 Company deregistrations Page 43 Change of company status Page 404 Company reinstatements Page 405 ISSN 1445-6060 Available from www.asic.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia, 2001 Email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 5179AA, Melbourne Vic 3001 Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC Gazette ASIC 16/02, Tuesday, 9 April 2002 Company deregistrations Page 43= = CORPORATIONS ACT 2001 Section 601CL(5) Notice is hereby given that the names of the foreign companies mentioned below have been struck off the register. Dated this nineteenth day of March 2002 Brendan Morgan DELEGATE OF THE AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Name of Company ARBN ABBOTT WINES LIMITED 091 394 204 ADERO INTERNATIONAL,INC. 094 918 886 AEROSPATIALE SOCIETE NATIONALE INDUSTRIELLE 083 792 072 AGGREKO UK LIMITED 052 895 922 ANZEX RESOURCES LTD 088 458 637 ASIAN TITLE LIMITED 083 755 828 AXENT TECHNOLOGIES I, INC. 094 401 617 BANQUE WORMS 082 172 307 BLACKWELL'S BOOK SERVICES LIMITED 093 501 252 BLUE OCEAN INT'L LIMITED 086 028 391 BRIGGS OF BURTON PLC 094 599 372 CANAUSTRA RESOURCES INC. -

Thomas Percy: Literary Anthology and National Invention

Thomas Percy: Literary Anthology and National Invention Danni Lynn Glover MA (Hons.), Scottish Language and Literature Faculty of Arts, Glasgow University 2012 MPhil., English language Faculty of Arts, Glasgow University 2014 Faculty of Arts, Ulster University Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) October 2017 I confirm that the total word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words. Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Note on Access to Contents iii Introduction 1 Contexts 1 A note on ‘Cultural Anglicanism’ 16 The Enlightenment Context 17 Research Questions and Methodologies 19 Review of Literature 30 Chapter one – Anthology as national canvas 45 Introduction 45 Anthology and Gothic Ruin 46 The Case for Anthologies of Translation 57 Identity and Ideology 61 Conclusion 71 Chapter two – National Identity in the Translated Anthology 73 Introduction 73 Recognising Identity in the Translated Anthology 73 Percy and Macpherson 82 Five Pieces of Runic Poetry 87 Hau Kiou Choaan and Miscellaneous Pieces 97 Conclusion 110 Chapter three – Britain and the Reliques 112 Introduction 112 Anthological Pretexts 113 Collaborators 118 Locating Anthology 123 Nation as Anthology, Anthology as Nation 133 The Britains of the Reliques 141 Conclusion 155 Chapter four – Applied Anthology 158 Introduction 158 Paratexts 158 Hearing Voices: Heteroglossia 179 Decolonizing the Canon: Colonialism, Gender, Labour 189 Conclusion 213 Conclusion 215 Future research 218 Final reflections 223 Bibliography 225 i Acknowledgements I offer my sincerest gratitude to my primary supervisor, Dr Frank Ferguson, whose knowledge, dedication, and sincere interest in my research has been indispensable at all stages of preparing this thesis. Thanks are also owed to Dr James Ward, whose thoughtful attention to detail made him an exemplary second supervisor. -

The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border

*> THE MINSTRELSY OF THE SCOTTISH BORDER — A' for the sake of their true loves : I ot them they'll see nae mair. See />. 4. The ^Minstrelsy of the Scottish "Border COLLECTED BY SIR WALTER SCOTT EDITED AND ARRANGED WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY ALFRED NOYES AND SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN MACFARLANE NEW YORK FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY PUBLISHERS • • * « * TO MARGARET AND KATHARINE BRUCE THIS EDITION OF A FAMOUS BOOK OF THEIR COUNTRY IS DEDICATED WITH THE BEST WISHES OF ITS EDITOR :593:3£>3 CONTENTS l'AGE Sir Patrick Spens I 6 The Wife of Usher's Well Clerk Saunders . 9 The Tvva Corbies 15 Barthram's Dirge 16 The Broom of Cowdenknows iS The Flowers of the Forest 23 25 The Laird of Muirhead . Hobbie Noble 26 Graeme and Bewick 32 The Douglas Tragedy . 39 The Lament of the Border Widow 43 Fair Helen 45 Fause Foodrage . 47 The Gay Goss-Hawk 53 60 The Silly Blind Harper . 64 Kinmont Willie . Lord Maxwell's Good-night 72 The Battle of Otterbourne 75 O Tell Me how to Woo Thee 81 The Queen's Marie 83 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 88 90 The Lass of Lochroyan . The Young Tamlane 97 vii CONTENTS PACE 1 The Cruel Sister . 08 Thomas the Rhymer "3 Armstrong's Good-night 128 APPENDIX Jellon Grame 129 Rose the Red and White Lilly 133 O Gin My Love were Yon Red Rose 142 Annan Water 143 The Dowie Dens of Yarrow .46 Archie of Ca'field 149 Jock o' the Side . 154 The Battle of Bothwell Bridge 160 The Daemon-Lover 163 Johnie of Breadislee 166 Vlll LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS "A' for the sake of their true loves ;") ^ „, .,,/". -

Midsummer Storybooks

Description Magic Items Pick 2: Subtract your Popularity from 3 and choose that little coat, pretty, plump, rosy cheeks, youngest, many magic items from the following: smallest, willful, hair of gold, hair of silver, lovely, magic stones (2) Child clad in leaves, hooded, thick brows, humble, joyful, bread crumbs (1) conceited, curly hair, loveable, blue coat, red shoes, horn of waking (1) “All children, except too spoiled, headstrong, polite, frills, patched, little, wooden horse (2) sometimes good, sometimes bad, fond of good lamp of seven kingdoms (1) one, grow up.” things singing quilt (1) - Peter Pan and Wendy, James M. Barrie pan pipes (2) Mundane Life cursed mirror shards (2) Pick 1: treasure map (1) babysitter, paperboy, thief, runaway, foster child, silver knife (1) (magical weapon 1) hacker, volunteer, scout, child singer, child star, little black casket (2) abductee, skateboarder, busker, dog walker, student, wooden sword (2) (magical weapon 2) assistant, urchin, bellhop, dish washer, assembly any wealth 1 trinket line worker, bagger, caretaker, gardener, juvenile delinquent Experience Improve Stats Improvements You are filled with the pure wonder Choose one set: Add +1 to your Courage (maximum of +3). Courage +1, Brawn 0, Cunning +2, Wisdom -2 Add +1 to your Brawn (maximum of +3). and innocence of childhood, for you Courage 0, Brawn +1, Cunning +2, Wisdom -2 Add +1 to your Cunning (maximum of +3). Courage +2, Brawn -2, Cunning +2, Wisdom -1 Add +1 to your Wisdom (maximum of +3). are an eternal child. Tricks and tales Courage -1, Brawn -1, Cunning +2, Wisdom +1 Choose a new Child move. -

The Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire

LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class VZQlo ' i" /// s Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/balladssongsofayOOpaterich THE BALLADS AND SONGS OF AYRSHIRE, ILLUSTRATED WITH SKETCHES, HISTORICAL, TRADITIONAL, NARRATIVE AND BIOGRAPHICAL. Old King Coul was a merry old soul, And a jolly old soul was he ; Old King Coul he had a brown bowl, And they brought him in fiddlers three. EDINBURGH: THOMAS G. STEVENSON, HISTORICAL AND ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLER, 87 PRINCES STREET. MDCCCXLVII. — ; — CFTMS IVCRSI1 c INTRODUCTION. Renfrewshire has her Harp—why not Ayrshire her Lyre ? The land that gave birth to Burns may well claim the distinction of a separate Re- pository for the Ballads and Songs which belong to it. In this, the First Series, it has been the chief object of the Editor to gather together the older lyrical productions connected with the county, intermixed with a slight sprinkling of the more recent, by way of lightsome variation. The aim of the work is to collect those pieces, ancient and modern, which, scattered throughout various publications, are inaccessible to many readers ; and to glean from, oral recitation the floating relics of a former age that still exist in living remembrance, as well as to supply such in- formation respecting the subject or author as maybe deemed interesting. The songs of Burns—save, perhaps, a few of the more rare—having been already collected in numerous editions, and consequently well known, will form no part of the Repository. In distinguishing the Ballads and Songs of Ayrshire, the Editor has been, and will be, guided by the connec- tion they have with the district, either as to the author or subject ; and now that the First Series is before the public, he trusts that, whatever may be its defects, the credit at least will be given Jiim of aiming, how- ever feebly, at the construction of a lasting monument of the lyrical literature of Ayrshire. -

040 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books Mn. VVI LCI AM S1I .A. K- li- S 1^ -A. 1^. t/ S COMEDIES, HISTORICS, & TRAGED1E S. Pulliihid accorv LO 0 Priqtedty like laggard, aod Ed.Blount. 1 <5i}- Facsimile of the title-page of the First Folio Shakespeare, dated 1623 From the original in the New York Public Library, New York THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME I From Chaucer to Gray W//A Introductions and Notes Volume 40 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1910 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. S. A. CONTENTS GEOFFREY CHAUCER PAGE THE PROLOGUE TO THE CANTERBURY TALES n THE NUN'S PRIEST'S TALE 34 TRADITIONAL BALLADS THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY 51 THE TWA SISTERS 54 EDWARD 5 6 BABYLON: OR, THE BONNIE BANKS O FORDIE 58 HIND HORN 59 LORD THOMAS AND FAIR ANNET 61 LOVE GREGOR 65 BONNY BARBARA ALLAN 68 THE GAY GOSS-HAWK 69 THE THREE RAVENS 73 THE TWA CORBIES 74 SIR PATRICK SPENCE 74 THOMAS RYMER AND THE QUEEN OF ELFLAND 76 SWEET WILLIAM'S GHOST 78 THE WIFE OF USHER'S WELL 80 HUGH OF LINCOLN 81 YOUNG BICHAM 84 GET UP AND BAR THE DOOR 87 THE BATTLE OF OTTERBURN 88 CHEVY CHASE 93 JOHNIE ARMSTRONG 101 CAPTAIN CAR 103 THE BONNY EARL OF MURRAY 107 KINMONT WILLIE ' 108 BONNIE GEORGE CAMPBELL 114 THE DOWY HOUMS O YARROW 115 MARY HAMILTON 117 THE BARON OF BRACKLEY 119 BEWICK AND GRAHAME 121 A GEST OF ROBYN HODE 128 1 2 CONTENTS ANONYMOUS PAG* BALOW 186 THE OLD CLOAK 188 JOLLY GOOD ALE AND OLD .. -

The Ballad/Alan Bold Methuen & Co

In the same series Tragedy Clifford Leech Romanticism Lilian R Furst Aestheticism R. V. Johnson The Conceit K. K Ruthven The Ballad/Alan Bold The Absurd Arnold P. Hinchliffe Fancy and Imagination R. L. Brett Satire Arthur Pollard Metre, Rhyme and Free Verse G. S. Fraser Realism Damian Grant The Romance Gillian Beer Drama and the Dramatic S W. Dawson Plot Elizabeth Dipple Irony D. C Muecke Allegory John MacQueen Pastoral P. V. Marinelli Symbolism Charles Chadwick The Epic Paul Merchant Naturalism Lilian R. Furst and Peter N. Skrine Rhetoric Peter Dixon Primitivism Michael Bell Comedy Moelwyn Merchant Burlesque John D- Jump Dada and Surrealism C. W. E. Bigsby The Grotesque Philip Thomson Metaphor Terence Hawkes The Sonnet John Fuller Classicism Dominique Secretan Melodrama James Smith Expressionism R. S. Furness The Ode John D. Jump Myth R K. Ruthven Modernism Peter Faulkner The Picaresque Harry Sieber Biography Alan Shelston Dramatic Monologue Alan Sinfield Modern Verse Drama Arnold P- Hinchliffe The Short Story Ian Reid The Stanza Ernst Haublein Farce Jessica Milner Davis Comedy of Manners David L. Hirst Methuen & Co Ltd 19-+9 xaverslty. Librasü Style of the ballads 21 is the result not of a literary progression of innovators and their acolytes but of the evolution of a form that could be men- 2 tally absorbed by practitioners of an oral idiom made for the memory. To survive, the ballad had to have a repertoire of mnemonic devices. Ballad singers knew not one but a whole Style of the ballads host of ballads (Mrs Brown of Falkland knew thirty-three separate ballads). -

English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study

British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Vol.11 No.I (2012) ©BritishJournal Publishing, Inc. 2012 http://www.bjournal.co.uk/BJASS.aspx English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study Elmas Sahin Assist. Prof. Elmas Sahin, Cag University, The Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkey, [email protected], Tel: +90 324 651 48 00, fax: +90 324 651 48 11 Abstract Although "ballad" whose origins based on the medieval period in the Western World; derived from Latin, and Italian word 'ballata' (ballare :/ = dance) to “turku” occurring approximately in the same centuries in the Eastern World, whose sources of the'' Turkish'' word sung by melodies in spoken tradition of Anatolia, a term given for folk poetry /songs "Turks" emerged in different nations and different cultures appear in similar directions. When both Ballads and folk songs as products of different cultures in terms of topics, motifs, structures and forms were analyzed are similar in many respects despite of exceptions. Here we will handle and evaluate the ballads and turkus, folk songs, being the products of different countries and cultures, according to the Comparative Literature and Criticism, and its theory by focusing the selected works, by means of a pluralistic approach. In this context these two literary genres having literary values, similar and different aspects in structure and content will be evaluated compared and contrasted in light of various methods as formal ,structural, reception and historical approaches. Keywords: ballad, turku, folk songs, folk poems, comparative literature 33 British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Introduction Although both Ballad and Türkü are the products of different countries and cultures, except for some unimportant differences, they have similar aspects in terms of their subject, theme, motive, structure and form.