THE GREAT POMPEIAN BROTHEL-GAP Eminent Victorians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Night Network Review

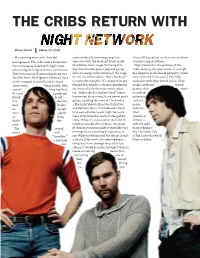

THE CRIBS RETURN WITH Shera Tanvir Editor-in-Chief After parting ways with their old and melodically swooning song that They still stayed true to their core and their management, The Cribs took a break from contrasts with the loud and brash tracks sound is unique to them. the music scene to deal with legal issues that follow. Main single “Running Into Night Network is the epitome of The concerning their rights to their own music. You” blends indie power pop and garage Cribs, defying all expectations. It exempli- They were unsure if continuing music was rock. Its energy and passion sets the stage fies elegance in the face of adversity, rather ideal for them. Foo Fighters frontman Dave for the rest of the album. “She’s My Style” than throwing in the towel. The Cribs Grohl swooped in and offered the band is especially energetic. It’s meant to be per- reconnect with their love of music. They access to his home studio. After formed live, which is a shame considering made a euphoric record several long legal bat- the limits of COVID on the music indus- despite their night- tles and a pandemic try. “Under the Bus Station Clock” layers marish ex- friend- ly self harmonies, distant vocals and power punk periences pro- duction, guitar, recalling the work of The Strokes. with the they finally The Cribs’ debut album was full of wit music re- leased and dynamic lyrics. It introduced a band industry. their eighth that wanted to be heard. Night Network Their al- bum, steps away from this and let’s the guitars stamina is Night Net- shine. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Background The present study concerns materials used for Pompeian wall paintings.1 In focus are plasters of the early period, related to the Samnite period and the so called First style. My earlier experiences the field of ancient materials were studies of Roman plasters at the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta and fragments of wall decorations from the demolished buildings underneath the church San Lorenzo in Lucina in Rome. These studies led to the hypothesis that technology reflects not only the natural (geographical) resources available but also the ambitions within a society, a moment in time, and the economic potential of the commissioner.2 Later, during two years within the Swedish archaeological project at Pompeii, it was my task to study the plasters used in one of the houses of insula V 1, an experience that led to the perception that specific characteristics are linked to plasters used over time. In the period 2003-2005, funding by the Swedish Research Council made possible to test the hypotheses. The present method was developed at insula I 9 and the Forum of Pompeii with the approval of the Soprintendenza archeological di Pompei and in collaboration with the directors of two international archaeological teams.3 It became evident that plaster’s composition changes over time, and eight groups of chronologically pertinent plasters were identified and defined A-H. Based on these results, I assume there is a connection between the typology and the relative chronology in which the plasters appear on the walls. I also believe these factors are related not only in single buildings or quarters but over the site and that, hypothetically, the variations observed are related to technology, craftsmanship and fashion. -

Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland Joseph Gary Norman College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Joseph Gary, "Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625384. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-31jw-vn87 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY WHARF CONSTRUCTION IN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND A Thesis .Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Joseph Gary Norman 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joseph Gary Norman Approved, May 1987 Carol Ballingall o Theodore Reinhart 4jU-/V £ ^ Anne E. Yentsch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .................................................................................................................iv -

Journal of Roman Archaeology

JOURNAL OF ROMAN ARCHAEOLOGY VOLUME 26 2013 * * REVIEW ARTICLES AND LONG REVIEWS AND BOOKS RECEIVED AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Table of contents of fascicule 2 Reviews V. Kozlovskaya Pontic Studies 101 473 G. Bradley An unexpected and original approach to early Rome 478 V. Jolivet Villas? Romaines? Républicaines? 482 M. Lawall Towards a new social and economic history of the Hellenistic world 488 S. L. Dyson Questions about influence on Roman urbanism in the Middle Republic 498 R. Ling Hellenistic paintings in Italy and Sicily 500 L. A. Mazurek Reconsidering the role of Egyptianizing material culture 503 in Hellenistic and Roman Greece S. G. Bernard Politics and public construction in Republican Rome 513 D. Booms A group of villas around Tivoli, with questions about otium 519 and Republican construction techniques C. J. Smith The Latium of Athanasius Kircher 525 M. A. Tomei Note su Palatium di Filippo Coarelli 526 F. Sear A new monograph on the Theatre of Pompey 539 E. M. Steinby Necropoli vaticane — revisioni e novità 543 J. E. Packer The Atlante: Roma antica revealed 553 E. Papi Roma magna taberna: economia della produzione e distribuzione nell’Urbe 561 C. F. Noreña The socio-spatial embeddedness of Roman law 565 D. Nonnis & C. Pavolini Epigrafi in contesto: il caso di Ostia 575 C. Pavolini Porto e il suo territorio 589 S. J. R. Ellis The shops and workshops of Herculaneum 601 A. Wallace-Hadrill Trying to define and identify the Roman “middle classes” 605 T. A. J. McGinn Sorting out prostitution in Pompeii: the material remains, 610 terminology and the legal sources Y. -

Policy Brief

POLICY BRIEF USING CLIMATE RELEVANT INNOVATION-SYSTEM BUILDERS TO ENHANCE ACCESS TO CLIMATE FINANCE FOR NDC DELIVERY INSIGHTS FROM THE CRIBs 2017 EAST AFRICA POLICY MAKERS’ WORKSHOP REUBEN MAKOMERE, JOANES ATELA AND ROB BYRNE Climate Resilient Economies Programme Policy Brief 008/2017 Key messages Previous international Implementing CRIBs will play an Coordinated imple- 1 climate finance mech- 2 CRIBs (Climate Rel- 3 intermediary role 4 mentation of CRIBs anisms such as the evant Innovation- between all relevant across East Africa will Clean Development system Builders) actors within any create opportunities Mechanism (CDM) can enable East given country, build- for regional integra- are not helping low African countries ing innovation systems tion and lobbying and middle income to design and im- around appropriate power for suitable countries due to a plement competi- climate technologies climate technologies failure to address wid- tive climate change by strengthening links and finance. er innovation system projects that at- between actors and building and related tract international leveraging funding By connecting actors technological capacity climate finance. from international 5 and institutions, na- building needs.. climate funds like the tionally and regionally, Green Climate Fund, CRIBs create enabling as well as increasing environments for cli- private investment. mate investments that are more inclusive, eq- uitable and supportive to poverty reduction and economic devel- opment efforts. INTRODUCTION issue. Innovation systems have been proven to explain International climate finance mechanisms have often the economic development of a wide range of countries failed to deliver against the climate technology needs of including all of the OECD countries and the so-called low and middle income countries. -

Schwarz, Lotte Oral History Interview

Bates College SCARAB Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 6-11-1990 Schwarz, Lotte oral history interview Steve Hochstadt Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/shanghai_oh SHANGHAI JEWISH COMMUNITY BATES COLLEGE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT LEWISTON, MAINE , _____________________________________________________________ _ LOTTE SCHWARZ SEAL BEACH, CALIFORNIA JUNE 11, 1990 Interviewer: Steve Hochstadt Transcription: Meredyth Muth Jessica Oas Stefanie Pearson Philip Pettis Steve Hochstadt © 2001 Lotte Schwarz and Steve Hochstadt Steve Hochstadt: But that's what I am interested in, so ... Lotte Schwarz: What I wanted to say is before I, before we went to Shanghai, and that was before I got married, I worked for the Hilfsverein. You know what the Hilfsverein, Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden? Hochstadt: Yes, many people have talked about it helping them to go ... Schwarz: Yeah. That's what we did and I worked there. I was a secretary for different provinces, for the province Hannover, W estfalen, Hessen-Kassel, different provinces. And my boss was a former lawyer, who couldn't go to, to the courts any more. You know they didn't let the Jews go into court any more. So, and he had a family with three little kids, so he was the first one, he got the, he was a representative for the Hilfsverein for the different provinces around Hannover. And I was his secretary. So he was kind of out, I mean, he was so depressed for everything, so I did most of the work. What we did was, most people came only in to, that we paid to get the money that they could go somewhere overseas, or overseas, or in the beginning, they could still go to England or France, if they had people there. -

Fire Research Station

Fire Research Note No 979 FULLY DEVELOPED COMPARTMENT FIRES: NEW CORRELATIONS OF BURNING RATES by P H THOMAS and L NILSSON August 1973 FIRE RESEARCH STATION © BRE Trust (UK) Permission is granted for personal noncommercial research use. Citation of the work is allowed and encouraged. Fire Research Station BOREHAMWOOD Hertfordshire WD62BL Tel 01. 953. 6177 F.R.Note No 979 August 1973 FULLY DEVEIDPED COMPARTMENT FIRES: NEW GORRELATIONS OF BURNING RATES by P H Thomas and L Nilsson SUMMARY Three main regimes of behaviour can be identified for fully developed crib fires in compartments. In one of these crib porosity controls and in another fuel surface; these correspond to similar regimes for cribs in the open. The third regime is the well known ventilation controlled regime. Nilsson's data have accordingly been analysedin terms of these regimes and approximate criteria established for the boundaries between them. It is shown from these that in the recent G.I.B.lnternational programme the experiments with larger spacing between the crib sticks were representative of fires not significantly influenced by fuel porosity. : The transition between ventilation controlled and fuel surface controlled regimes may occur at values of the fire load per unit ventilation area, lower than previously estimated. In view of the increase in interest in fuels other than wood on which most if not. ' all empirical burning rates are based, a theoretical model of the rate of burning of window controlled compartment fires is formulated. With known and plausible physical properties inserted it shows that the ratio of burning rate R to the ventilation 1 paramater A H"2" ,where A is window area and H is window hei~ht,is not strictly w w w w I constant as often assumed but can increase for low values of AwH;;~ where ~ is the internal surface area of compartment. -

![Alexander Conze, on the Origin of the Visual Arts, Lecture Held on July 30, 1896 [In the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences] Translated and Edited by Karl Johns](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2981/alexander-conze-on-the-origin-of-the-visual-arts-lecture-held-on-july-30-1896-in-the-royal-prussian-academy-of-sciences-translated-and-edited-by-karl-johns-1432981.webp)

Alexander Conze, on the Origin of the Visual Arts, Lecture Held on July 30, 1896 [In the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences] Translated and Edited by Karl Johns

Alexander Conze, On the Origin of the Visual Arts, Lecture held on July 30, 1896 [in the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences] translated and edited by Karl Johns Editor’s introduction: Alexander Conze: The Bureaucrat and Art- Historiography Like a number of his colleagues, Alexander Conze (Hanover December 10, 1831- Berlin July 19, 1914), came to classical archaeology after first studying law. His interests and gifts seem to have tended more toward curatorial and administrative work rather than lecturing, and he will be primarily remembered for his part in bringing the Pergamon Altar to the Berlin museums. It may therefore seem ironic that he nevertheless had a great influence as a teacher and probably the greatest influence in another field, which was only later to be defined and brought to fruition in academia by his students as ‘the history of art.’ For the purposes of art historiography it is therefore significant that after nearly ten years at Halle as Extraordinarius, he was called to the University of Vienna as Ordinarius, taught from 1869 to 1877, where Franz Wickhoff, Alois Riegl, Emanuel Löwy and Julius Schlosser, among others, were influenced by his teachings. In the lectures given by Conze to the Prussian academy later in his career, it is not difficult to recognize a similarity to Schlosser in the binocular attraction of more abstract questions on the one hand and the aesthetic appeal of the individual object on the other. Conze also anticipated and presumably inspired the later studies made by Ernst Garger on the ground in relief sculpture and the historical place of the Monument of the Julii. -

D003: Wall Painting Techniques 1 Introduction Pompeii And

D003: Wall painting techniques Introduction Pompeii and Herculaneum have been described as towns frozen in time. Houses and villas with their furniture, food, people, jewellery and pets have been preserved. Organic materials were better preserved at Herculaneum as carbonised materials (see the wine shop figure 1) because of the pyroclastic surges. Figure 1: Wine shop at Herculaneum showing gallery and amphorae Our knowledge has been enhanced by more systematic and scientific excavations in recent years. One thing that strikes all visitors to Pompeii and Herculaneum is the amount of colour on the walls of the buildings. It is perhaps the most obvious feature of Roman art. Roman fresco techniques Many of the wall paintings or frescos adorned walls not just inside rich villas, but also inside private houses and public buildings. Depending on the function of the room, walls might be painted with imaginary architecture, still life, mythological scenes, or purely decorative motifs. Many of these motifs were derived from pattern books carried by the artists. So despite the lack of physical evidence of other forms, it is reasonable to assume that many other art objects would have shown subjects similar to those found on the painted walls. Why is the wall art or fresco painting so important? 1 D003: Wall painting techniques Can fresco painting tell us anything about the development of art in the Ancient Roman Period? How did they paint in fresco? It is clear the ancient Romans decorated the interior walls of their houses with paintings executed on wet plaster, a technique known as fresco (meaning on fresh plaster). -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule. For centuriesarchaeologists have thosefrom wealthy families and freedwomen. exploited the Vesuvius disaster,revealing detailed evidence about the last hours of the town and its doomed inhabitants.Excavation has also uncov- ered factsabout the lives of Pompieans in happier evidence about the female membersof society.It times,when the rich soil on the slopes of Mount is an importantsource of information,in fact, Vesuvius yielded abundant harvestsof grapes, about the women of antiquityin general. Yet ar- olives, fruitsand vegetables. In those days, a vol- chaeology is a source that has gone largelyuntap- canic holocaust had seemed an impossibility.After ped. Studies of the women of ancient timeshave all, Pompeii had flourishedsafely for six hundred tended to draw theirevidence fromliterature, years,basking in the sun of southern Italy. Within even though the remarksabout women in ancient three days, however,the entire citywas buried by literatureare few in number and often lack objec- volcanic ash. Eventuallyeven its verylocation was tivity.Since Pompeii provides more archaeological forgotten.As layersof rich soil accumulated over evidence about women than most other ancient the site,what had been a thrivingcity became fer- sites except Rome itself,the failureto come to tile countryside. -

Literaturliste.Pdf

A# Mark B. Abbe, A Roman Replica of the ‘South Slope Head’. Polychromy and Identification, Source. Notes in Abbe 2011 History of Art 30, 2011, S. 18–24. Abeken 1838 Wilhelm Abeken, Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände / Kunstblatt 19, 1838. Abgusssammlung Bonn 1981 Verzeichnis der Abguss-Sammlung des Akademischen Kunstmuseums der Universität Bonn (Berlin 1981). Abgusssammlung Göttingen Klaus Fittschen, Verzeichnis der Gipsabgüsse des Archäologischen Instituts der Georg-August-Universität 1990 Göttingen (Göttingen 1990). Abgusssammlung Zürich Christian Zindel (Hrsg.), Verzeichnis der Abgüsse und Nachbildungen in der Archäologischen Sammlung der 1998 Universität Zürich (Zürich 1998). ABr Paul Arndt – Friedrich Bruckmann (Hrsg.), Griechische und römische Porträts (München 1891–1942). Michael Abramić, Antike Kopien griechischer Skulpturen in Dalmatien, in: Beiträge zur älteren europäischen Abramić 1952 Geschichte. FS für Rudolf Egger I (Klagenfurt 1952) S. 303–326. Inventarium Von dem Königlichen Schloße zu Sanssouci, und den neuen Cammern, so wie solches dem Acta Inventur Schloss Castellan Herr Hackel übergeben worden. Aufgenommen den 20 Merz 1782, fol. 59r-66r: Nachtrag Mai Sanssouci 1782−1796 1796, in: Acta Die Inventur Angelegenheiten von Sanssouci betreffend. Sanssouci Inventar 1782-1825, vol. I. (SPSG, Hist. Akten, Nr. 5). Acta betreffend das Kunst- und Raritaeten-Cabinet unter Aufsicht des Herrn Henry 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801. Acta Kunst-und Königliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, Abschnitt I. von 1700–1811, Abth. XV., No. 3 die Königs Cabinette Raritätenkabinett 1798–1801 a[?] des Kunst-Medaillen u. Nat. Cab. Acta Commissionii Reclamationen über gestohlene Kunstsachen. 1814, vol. 1, fol. 4r–33v: Bericht Rabes über gestohlene Kunstsachen an Staatskanzler von Hardenberg, 12. Februar 1814, fol. 81r–82r: Brief Acta Kunstsachen 1814 Henrys an Wilhelm von Humboldt, 26. -

Great Pompeii Project

Archaeological Area of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, Italy, n. 829 1. Executive summary of the report Soon after the collapse of the Schola Armaturarum, UNESCO carried out several missions, involving ICOMOS and UNESCO experts, at the sites of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, specifically on 2-4 December 2010 and 10 – 13 January 2011, on 7-10 January 2013 and 8-12 November 2014. These inspections led to the formulation of a set of recommendations, which have ultimately been summarised in decision 39 COM 7B, adopted at the 39th meeting of the World Heritage Committee, to which this report is a reply. Over the years, many steps forward have been made in the conservation and management of the property. Regarding the Grande Progetto Pompeii (Great Pompeii Project), the State Party has ensured its continuation with a further European financing of 45 M€ and by maintaining the General Project Management organisation and the Great Pompeii Unit until 31 December 2019. A further two items of funding have been received: 40 M€ from the Italian government and 75 M€ from the Special Superintendency of Pompeii, which has been granted financial, administrative and management autonomy. The more recent inspection by UNESCO/ICOMOS identified 5 buildings at risk in the site of Pompeii: Casa dei Casti Amanti, Casa delle Nozze d’argento, Schola Armaturarum, Casa di Trebius Valens and Casa dei Ceii. Conservation interventions were then planned for all these buildings, which, to date, are either still underway or have been completed, or which will soon start. Almost all the legal problems that prevented the start of the works have been solved and now it will be possible to carry out the safety works on and restore the structures of the Schola Armaturarum; open the Antiquarium to the public; and continue the improvement works on the Casina dell’Aquila.