Schwarz, Lotte Oral History Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Night Network Review

THE CRIBS RETURN WITH Shera Tanvir Editor-in-Chief After parting ways with their old and melodically swooning song that They still stayed true to their core and their management, The Cribs took a break from contrasts with the loud and brash tracks sound is unique to them. the music scene to deal with legal issues that follow. Main single “Running Into Night Network is the epitome of The concerning their rights to their own music. You” blends indie power pop and garage Cribs, defying all expectations. It exempli- They were unsure if continuing music was rock. Its energy and passion sets the stage fies elegance in the face of adversity, rather ideal for them. Foo Fighters frontman Dave for the rest of the album. “She’s My Style” than throwing in the towel. The Cribs Grohl swooped in and offered the band is especially energetic. It’s meant to be per- reconnect with their love of music. They access to his home studio. After formed live, which is a shame considering made a euphoric record several long legal bat- the limits of COVID on the music indus- despite their night- tles and a pandemic try. “Under the Bus Station Clock” layers marish ex- friend- ly self harmonies, distant vocals and power punk periences pro- duction, guitar, recalling the work of The Strokes. with the they finally The Cribs’ debut album was full of wit music re- leased and dynamic lyrics. It introduced a band industry. their eighth that wanted to be heard. Night Network Their al- bum, steps away from this and let’s the guitars stamina is Night Net- shine. -

Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland Joseph Gary Norman College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Joseph Gary, "Eighteenth-Century Wharf Construction in Baltimore, Maryland" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625384. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-31jw-vn87 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY WHARF CONSTRUCTION IN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND A Thesis .Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Joseph Gary Norman 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joseph Gary Norman Approved, May 1987 Carol Ballingall o Theodore Reinhart 4jU-/V £ ^ Anne E. Yentsch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .................................................................................................................iv -

Policy Brief

POLICY BRIEF USING CLIMATE RELEVANT INNOVATION-SYSTEM BUILDERS TO ENHANCE ACCESS TO CLIMATE FINANCE FOR NDC DELIVERY INSIGHTS FROM THE CRIBs 2017 EAST AFRICA POLICY MAKERS’ WORKSHOP REUBEN MAKOMERE, JOANES ATELA AND ROB BYRNE Climate Resilient Economies Programme Policy Brief 008/2017 Key messages Previous international Implementing CRIBs will play an Coordinated imple- 1 climate finance mech- 2 CRIBs (Climate Rel- 3 intermediary role 4 mentation of CRIBs anisms such as the evant Innovation- between all relevant across East Africa will Clean Development system Builders) actors within any create opportunities Mechanism (CDM) can enable East given country, build- for regional integra- are not helping low African countries ing innovation systems tion and lobbying and middle income to design and im- around appropriate power for suitable countries due to a plement competi- climate technologies climate technologies failure to address wid- tive climate change by strengthening links and finance. er innovation system projects that at- between actors and building and related tract international leveraging funding By connecting actors technological capacity climate finance. from international 5 and institutions, na- building needs.. climate funds like the tionally and regionally, Green Climate Fund, CRIBs create enabling as well as increasing environments for cli- private investment. mate investments that are more inclusive, eq- uitable and supportive to poverty reduction and economic devel- opment efforts. INTRODUCTION issue. Innovation systems have been proven to explain International climate finance mechanisms have often the economic development of a wide range of countries failed to deliver against the climate technology needs of including all of the OECD countries and the so-called low and middle income countries. -

Fire Research Station

Fire Research Note No 979 FULLY DEVELOPED COMPARTMENT FIRES: NEW CORRELATIONS OF BURNING RATES by P H THOMAS and L NILSSON August 1973 FIRE RESEARCH STATION © BRE Trust (UK) Permission is granted for personal noncommercial research use. Citation of the work is allowed and encouraged. Fire Research Station BOREHAMWOOD Hertfordshire WD62BL Tel 01. 953. 6177 F.R.Note No 979 August 1973 FULLY DEVEIDPED COMPARTMENT FIRES: NEW GORRELATIONS OF BURNING RATES by P H Thomas and L Nilsson SUMMARY Three main regimes of behaviour can be identified for fully developed crib fires in compartments. In one of these crib porosity controls and in another fuel surface; these correspond to similar regimes for cribs in the open. The third regime is the well known ventilation controlled regime. Nilsson's data have accordingly been analysedin terms of these regimes and approximate criteria established for the boundaries between them. It is shown from these that in the recent G.I.B.lnternational programme the experiments with larger spacing between the crib sticks were representative of fires not significantly influenced by fuel porosity. : The transition between ventilation controlled and fuel surface controlled regimes may occur at values of the fire load per unit ventilation area, lower than previously estimated. In view of the increase in interest in fuels other than wood on which most if not. ' all empirical burning rates are based, a theoretical model of the rate of burning of window controlled compartment fires is formulated. With known and plausible physical properties inserted it shows that the ratio of burning rate R to the ventilation 1 paramater A H"2" ,where A is window area and H is window hei~ht,is not strictly w w w w I constant as often assumed but can increase for low values of AwH;;~ where ~ is the internal surface area of compartment. -

Stork Craft Recalls More Than 2.1 Million Baby Cribs Due to Drop-Side Defect Which Can Lead to Infant/Toddler Entrapment

GLOBAL INSURANCE GROUP News Concerning ALERT Recent Insurance Coverage Issues DECEMBER 1, 2009 STORK CRAFT RECALLS MORE THAN 2.1 MILLION BABY CRIBS DUE TO DROP-SIDE DEFECT WHICH CAN LEAD TO INFANT/TODDLER ENTRAPMENT Kevin M. Haas • 212.908.1322 • [email protected] Joseph A. Arnold • 215.665.2795 • [email protected] n November 23, 2009, the U.S. Consumer Product manufacturing dates between October, 1997 and December, Safety Commission (CPSC), in cooperation with Stork 2004, and the Fisher-Price logo-bearing cribs were first sold O Craft Manufacturing, Inc., of Canada, announced the in the United States in July, 1998. Major retailers in the United voluntary recall of more than 2.1 million Stork Craft drop-side States and Canada which sold the recalled cribs include BJs cribs, including nearly 150,000 cribs with a Fisher-Price logo. Wholesale Club, JCPenney, K-Mart, Meijer, Sears, USA Baby, Approximately 1.2 million of the recalled cribs were distributed and Wal-Mart stores. On-line retailers include Amazon.com, in the United States. BabiesRUs.com, Costco.com, Target.com, and Walmart.com. According to the recall notice, deficiencies with the plastic This is the second Stork Craft recall this year. In January, Stork hardware in the drop-side rail can result in detachment, leading Craft recalled over 500,000 cribs due to mattress support bracket to a dangerous gap between the rail and crib mattress where failures. Stork Craft received reports that the metal support infants and toddlers can become trapped. Stork Craft reported brackets would break, causing the mattress to collapse, which in 110 incidents of drop-side detachment. -

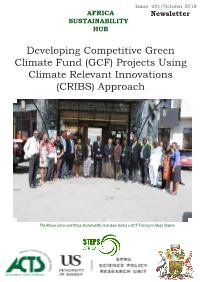

CRIBS) Approach

Issue 001/October 2018 AFRICA Newsletter SUSTAINABILITY HUB Developing Competitive Green Climate Fund (GCF) Projects Using Climate Relevant Innovations (CRIBS) Approach The African Union and Africa Sustainability Hub team during a GCF Training in Abuja Nigeria and the African Technology Policy Studies Network (ATPS). ASH is part of the STEPS Global Consortium at the University of Sussex which comprises six ‘hubs’ based in leading academic/research institutes across the globe in Africa, South Asia, China, Europe, Latin and North America with a vision for tackling the most THE AFRICA SUSTAINABILITY HUB (ASH) pressing sustainability challenges currently facing wwas established on a mutual partnership between the world and in the future. The Global Consortium Africa and UK leading research and policy think tanks provides an opportunity for lessons sharing on various on sustainability with the founding partners being the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) issues and African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS), the lessons across the continents, which is pertinent to STEPS Centre at the University of Sussex, the Africa Africa’s sustainability. Centre of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), sciences. The centre carries out carries out inter-disciplinary global research uniting development studies with science and technology studies to reduce poverty and bring about social justice. The Global Consortium at the Steps Centre unites 5 The Steps Centre is hosted in the UK by the continents through their hubs with a vision to tackle Institute -

Living, Reimagined

ARCHITECTURE IS THE WILL OF AN EPOCH TRANSLATED INTO SPACE. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Living, Reimagined. The Loggia welcomes you home with an open-air living space in South Jakarta. Designed by award-winning international architects, the development offers two, 20 stories towers with two & three-bedroom types of apartment units and with dozens of recreational amenities. It is located just minutes away from education and health institutions, and easy access to international airports. Perfect for couples and small family, the residence favors simplicity and clean design. Putting functionality as a vital role in today’s lifestyle needs. THINK BEYOND TRUST BEYOND THE ERA FARPOINT is an Indonesian real estate developer Tokyo Tatemono Co. Ltd. was established in 1896 that delivers and manages distinctive properties and is now the oldest property developer in Japan. of high quality standard and design. We are part With diverse interests in the property business, of the Gunung Sewu Group, a respected and well- Tokyo Tatemono is responsible for prestigious urban established business group in Indonesia. commercial developments, including the renowned Otemachi Tower where AMAN Tokyo is located on Embracing the vision, “To be a trusted real estate the top floors, premium residential developments, company with passionate employees delivering property management, and hospitality business. innovative products and quality experiences, creating value for stakeholders”, FARPOINT is backed by more Tokyo Tatemono Asia Pte. Ltd., established in than 30 years of solid experience in the development Singapore in 2014, is striving for further business and asset management of residential, commercial, opportunities in South East Asia by extending its hospitality and retail properties. -

Thecribs Biog Copy

BIOGRAPHY 2017 The seventh album by The Cribs is a bit of a paradox. It’s the quickest thing they’ve ever recorded, done and dusted in five days compared to a relatively leisurely seven for 2004’s self-titled debut, yet it’s also been six years in the making. It’s a release that’s going to surprise fans and it’s called – quite brilliantly – 24-7 Rock Star Shit. The album’s origins lie back in 2011, when the three Jarman brothers were making In The Belly Of The Brazen Bull. After recording the bulk of …Brazen Bull with producer Dave Fridmann at his isolated Tar- box Road Studio in upstate New York, they flew straight to Chicago’s Electrical Audio, home to another unique producer, the venerated Steve Albini, of Shellac and In Utero fame. There, over two cold November days, they stayed in the on-site dormitories, drank copious amounts of Albini’s trademark fluffy coffee and laid down four tracks for possible inclusion on …Brazen Bull, but which had such a spirit and sound of their own that they were laid aside for a rainy day. "We were really into the tracks, but they definitely had their own vibe - it didn't make sense to try and shoehorn them onto Brazen Bull" explains vocalist/bassist Gary Jarman. “Sometimes when we work with producers we’re pretty on their case, and that record was pretty involved” says drummer Ross Jarman. “With Steve we just took a step back and let him do his thing. We just wanted to get his raw power down on record.” When it came time for the next album, there was a plan to make two LPs to represent two distinct strands of their work: a pop record and a punk record, one polished and melodic, the other raw and un- derworked. -

Fuji Rock Music, Mud and Madness Summer Blockbusters Japan Inspired T-Shirts Dealing with Mental Health in Tokyo

Since 1970 FREE Vol.41 No.15 Aug 20th–Sep 2nd, 2010 www.weekenderjapan.com Including Japan’s largest online classifieds Fuji Rock Music, Mud and Madness Summer Blockbusters Japan Inspired T-Shirts Dealing with Mental Health in Tokyo CONTENTS Volume 41 Number 15 Aug 20th–Sep 2nd, 2010 4 Up My Street 12 5-9 Arts & Entertainment 10-11 Tokyo Tables 12-13 Fashion 14-15 Business 16-19 Feature: Fuji Rock 20-21 Weekender Bulletin Board 16 22-23 Real Estate 24-27 Parties, People & Places 28-29 Families 30-31 Products 32-33 Healthy & Responsible Living 30 34 Back in the Day PUBLISHER Ray Pedersen CONTRIBUTORS Kevin Jungnitsch, Cecelia Martinez, EDITOR Kelly Wetherille Sam Griffen, Simon Lawson, Christopher Jones, DESIGNER R. Paul Seymour Deborah Im, Ian de Stains OBE, Pankaj Arora WEB DEVELOPER Ricardo Costa MEDIA MANAGER Tomas Castro EST. Corky Alexander and Susan Scully, 1970 MEDIA CONSULTANTS Mary Rudow, Pia von Waldau RESEARCHER Rene Angelo Pascua OFFICE Weekender Magazine, 5th floor, Regency Shinsaka Building, 8-5-8 Akasaka, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-0052 Tel. 03-6846-5615 Fax: 03-6846-5616 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Owen Schaefer (Arts), Bill Hersey Email: [email protected] (Society), Stephen Parker (Products), Elisabeth Lambert (Health & Eco), Darrell Nelson (Sustainable Business) Cover photo by Kevin Jungnitsch Opinions expressed by Weekender contributors are not necessarily www.weekenderjapan.com those of the publisher. 3 WEEKENDER // Up My Street Maruyama-cho may not ring any bells with many Tokyoites, but this small Up My Street visits residential district has some unexpected surprises waiting for its visitors. -

BOSS Presents Sixth-Annual Lifetime Achievement Award

Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOSS Presents Sixth-Annual Lifetime Achievement Award PHOTO CREDT Niall Lea BOSS Lifetime Achievement Award Presented to Johnny Marr for His Incredible Contribution to the Music Industry Los Angeles, CA, January 19, 2021 —During NAMM Believe in Music Week 2021, BOSS presented its Sixth-Annual BOSS Lifetime Achievement Award to world-renowned musical icon, Johnny Marr. The BOSS Lifetime Achievement Award recognizes individuals for their invaluable contributions to the music industry while using BOSS gear throughout their careers. The global network of Roland and BOSS influencers now reaches more than 1,000 artists with a collective social reach exceeding 1 billion. Johnny Marr began his prolific career with The Smiths, founding a legacy as one of the most influential songwriters and guitarists in British independent music. His acclaimed solo career has seen multiple Top Ten albums, and continued collaborations with some of the greatest artists in contemporary music, including the Talking Heads, Electronic, Modest Mouse, The Cribs, The Avalanches, Hans Zimmer and Billie Eilish, recently recording the score and soundtrack for the forthcoming James Bond film, No Time to Die. Roland Europe Head of Artist Relations Jamie Franklin opened the awards presentation, offering that, “In terms of inspiring a generation to pick up a guitar and think differently about tone, melody, and life changing music, no one comes to mind more than Johnny Marr.” Artists from around the globe joined in to share their congratulations as well, including guitarists Billy Duffy, Rick Nielson and many more. BOSS President Yoshi Ikegami presented Marr with the award, and Marr expressed both honor and great surprise as it was not something Marr ever expected. -

MAKING CLIMATE FINANCE WORK for AFRICA Using Ndcs to Leverage Climate Relevant Innovation System Builders (CRIBS)

MAKING CLIMATE FINANCE WORK FOR AFRICA Using NDCs to Leverage Climate Relevant Innovation System Builders (CRIBS) AUTHORS: DAVID OCKWELL, ROB BYRNE, JOANES ATELA, MBEVA KENNEDY AND MAKOMERE REUBEN Climate Resilient Economies Programme Workshop Training Brief 2 /APRIL 2017 Training brief 2: Using CRIBs (Climate Relevant Innovation-system Builders) to implement NDCs Key messages Low and middle in- Regional coordina- CRIBs are an evidence CRIBs can ensure a 1 come countries should 2 tion in implement- 3 based policy vehicle/ 4 nationally determined, implement CRIBs - na- ing CRIBs to deliver institution through needs based ap- tionally nested, inter- NDCs represents which innovation sys- proach; fuelling green nationally networked a key opportunity tem building around growth, de-risking institutions that can for East African climate technologies innovation, informing leverage international countries to show can be achieved. enabling policy envi- climate finance and international lead- ronments, engaging deliver their NDCs ership (which will national stakeholders under the Paris Agree- likely be followed and mainstreaming ment.. by other develop- a focus on women, ing countries). youth and other mar- Regional and inter-re- ginalised groups. 5 gional coordination in lobbying for interna- tional climate finance will significantly in- crease lobbying power and the efficacy of CRIBs in delivering NDCs. CRIBs for building innovation systems & briefing note to this one: “Training brief 1: Why focus on delivering NDCs building innovation systems?” -

Johnny Marr Has Made a Second Solo Album—Co-Founder,Career of Playing Nice with Others

ISSUE #25 MMUSICMAG.COM REVIEWS HOLE JNobody’sOHNNY MARR Daughter [Universal] The Messenger [Sire] The first album released under the Hole moniker since 1998’s Celebrity Skin is really frontwoman Courtney Love’sSince leaving the Smiths in 1987, guitarist Johnny Marr has made a second solo album—co-founder,career of playing nice with others. He’s guested with such heavies as songwriter and lead guitarist Eric Erlandson isn’t involved,Talking Heads and Pet Shop Boys and even served stints with relative nor is any other previous Hole member. So it’s Love andwhippersnappers three Modest Mouse and the Cribs. Through it all, he’s seemingly ringers on 11 new songs—10 of which Love wrotemade with a conscious effort to avoid his signature sound—that rolling, bittersweet collaborators like Billy Corgan,jangle thatLinda definedPerry and newnot only the Smiths, but also indie rock as we know it. guitarist Micko Larkin. (Perry gets full credit on one tune, “Letter to God.”) On his solo debut, Marr comes closer than ever to revisiting the music of Much of the riveting intensity of the group’s 1990s heyday appears to havehis left early along 20s. with It’sher formernot all clean,Daniel Jackson chiming guitars—synths occasionally seep bandmates, but there are fl ashes here of the snarling Too often, though, the slower songs trip her up. While once fury Love deployed to suchthrough devastating the effect strumming, back in the harkingday. they back were showcases to Electronic, for harrowing Marr’s displays side of naked project emotion, She spits out her vocals withwith vengeful New Order’sdisdain on “SkinnyBernard Little Sumner—but Love sounds more The dispassionate Messenger these mostly days.