Population and Deforestation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R

LAND USE, LAND COVER AND SOIL SCIENCES – Vol. V – Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R. Penny DESERTIFICATION AND DEFORESTATION IN AFRICA R. Penny Environmental and Developmental Consultant/Practitioner, Cape Town, South Africa Keywords: arid, semi-arid, dry sub-humid, drought, drylands, land degradation, land tenure, sustainability Contents 1. Introduction 2. Global Context 3. Land Degradation in Africa Today 3.1. Geographical Regions 3.2. Socio-Economic Aspects 4. Causes and Consequences 4.1. Drought and Other Disasters 4.2. Water Quality and Availability 4.3. Loss of Vegetative Cover 4.4. Loss of Soil Fertility 4.5. Poverty and Population 4.6. Effect of Land Tenure 4.7. Health 5. Combating Desertification 5.1. Past Trends 5.2. Current Attempts to Combat Desertification 5.3. Synergy of the Three Sustainable Development Conventions 5.4. The Role of Science and Technology in Combating Desertification 5.5. Synergy in Environmental Policy Development 6. Future Perspectives: The Way Forward 7. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS Africa is particularly vulnerable to desertification. Two thirds of the continent consists of desert or drylands.SAMPLE The obvious causes of desertificatiCHAPTERSon and deforestation consist of major ecosystem changes, such as land conversion for various purposes, over- dependence on natural resources and several forms of unsustainable land use. However, the issue of desertification is inseparable from social problems such as poverty and land tenure issues. Politics, war and national disasters affect the movements of people and thus impact on the land. International trade policies as well play a part in land management and/or exploitation. -

Road Impact on Deforestation and Jaguar Habitat Loss in The

ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyright by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando 2008 Abstract The construction of roads, either as an economic tool or as necessity for the implementation of other infrastructure projects is increasing in the tropical forest worldwide. However, roads are one of the main deforestation drivers in the tropics. In this study we analyzed the impact of road investments on both deforestation and jaguar habitat loss, in the Mayan Forest. As well we used these results to forecast the impact of two road investments planned in the region. Our results show that roads are the single deforestation driver in low developed areas, whether many other drivers play and important role in high developed areas. In the short term, the impact of a road in a low developed area is lower than in a road in a high developed area, which could be the result of the lag effect between road construction and forest colonization. -

Hidden Deforestation in the Brazil - China Beef and Leather Trade 1

Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade 1 Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade Christina MacFarquhar, Alex Morrice, Andre Vasconcelos August 2019 Key points: China is Brazil’s biggest export market for cattle products, • Cattle ranching is the leading direct driver of deforestation which are a major driver of deforestation and other native and other native vegetation clearance in Brazil, and some vegetation loss in Brazil. This brief identifies 43 companies international beef and leather supply chains are linked to worldwide that are highly exposed to deforestation risk through these impacts. the Brazil-China beef and leather trade, and which have significant potential to help reduce this risk. The brief shows • China (including Hong Kong) is Brazil’s biggest importer of which of these companies have published policies to address beef and leather, and many companies linked to this trade are deforestation risk related to these commodities. It also reveals exposed to deforestation risk. the supplier-buyer relationships between these companies, • We identify 43 companies globally that are particularly exposed and how their connections may mean even those buyers with to the deforestation risk associated with the Brazil-China beef commitments to reduce or end deforestation may not be able to and leather trade and have the potential to reduce these risks. meet them. It then makes recommendations for the next steps companies can take to address deforestation risk. • Most of these companies have not yet published sustainable sourcing policies to address this risk. The companies include cattle processors operating in Brazil, processors and manufacturers operating in China, and • Most appear unable to guarantee that their supply chains are manufacturers and retailers headquartered in Europe and the deforestation-free, because they, or a supplier, lack a strong United States of America (US). -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

Human Population Growth and Its Implications on the Use and Trends of Land Resources in Migori County, Kenya

HUMAN POPULATION GROWTH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON THE USE AND TRENDS OF LAND RESOURCES IN MIGORI COUNTY, KENYA PAULINE TOLO OGOLA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Environmental Studies (Agroforestry and Rural Development) in the School of Environmental Studies of Kenyatta University NOVEMBR, 2018 1 DEDICATION To my loving parents, Mr. and Mrs. Ogola, With long life He will satisfy you i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I am grateful to the Man above who gave me strength and health throughout this study. For sure, His goodness and Mercies are new every day. Secondly, I am greatly indebted to my supervisors Dr. Letema and Dr. Obade for their wise counsel and patience. Thirdly, I would like to convey my utmost gratitude to my parents and siblings for their moral support and prayers. Special thanks to my brother Stephen Ogeda for supporting me financially. Finally, I wish to express many thanks to my colleagues at the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development and friends who have offered their support in kind and deed. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION………………………………………………………………………… Error! Bookmark not defined. DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………...i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT……………………………………………………………...ii LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………...vi LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………vii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS……………………………………………….viii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………i x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..1 1.1 Background to the Problem ......................................................................................... -

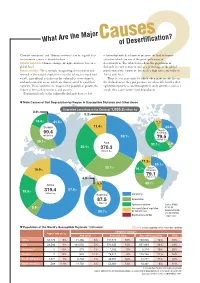

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

National Investment Plan to Reduce Deforestation and Forest Degradation (2018-2022)

Republic of Zambia Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources National Investment Plan to Reduce Deforestation and Forest Degradation (2018-2022) November 2017 -i- Executive Summary Zambia has approximately 49.9 million hectares of forest, representing approximately 66 percent of its total land mass and is subsequently one of the most forested countries in southern Africa. However, deforestation is a major problem, with annual rates estimated at around 250,000 to 300,000 hectares. Such numbers amount to the potential loss of 10 million hectares of forest in the next 30 years (IDLO, 2014). The key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Zambia are agricultural expansion (commercial and subsistence), heavy reliance on wood fuel – energy demand (charcoal and firewood), unsustainable timber extraction (both legal and illegal) and infrastructure development (e.g., mining and other large infrastructural developments). A study by UN-REDD, (2015) on the economic value of Zambia’s forest ecosystems showed that the direct and indirect values of forests are estimated to make a direct contribution equivalent to about 4.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) or US$957.5 million (using 2010 figures). However, when the multiplier effects of forestry and tourism-related activities on other sectors are considered, the overall or economy-wide contribution of forests to GDP is estimated to be at least 6.3% or US$1,277 million (Table 1). Forests are estimated to provide at least 1.4 million jobs, supporting 60% of rural Zambian households, heavily dependent upon the use of natural resources to supplement or sustain their livelihoods (UN-REDD., 2015). -

Deforestation and Social Risks in the Uk's Commodity

1 RISKY BUSINESS WORKING TOGETHER TO UNDERSTAND RISKS TO NATURAL CAPITAL DEFORESTATION AND SOCIAL RISKS IN THE UK’S COMMODITY SUPPLY CHAINS Lead authors: Steve Jennings, Richard Sheane and Catherine McCosker This report sets out research commissioned by WWF and the RSPB, carried out by consultancy 3Keel. It calculates the volume and source of UK imports (from 2011-15) of seven key forest-risk commodities: beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber, soy, and timber. This data is then used to estimate the location and scale of the land footprint created by UK consumption of these commodities, and explores the risks associated with this footprint. The research uses publicly available data and sets out the assumptions made in estimating the footprint and risks. The findings of this research are summarised and analysed in a separate report, which also includes recommendations on what UK government, companies and citizens can do to address the risks. Risky Business: Understanding the UK’s overseas footprint for deforestation-risk commodities Available at: wwf.org.uk/riskybusiness Reports published October 2017. Contents 1 Executive summary ........................................................................................... 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 5 2.1 About this document ............................................................................................ 6 3 Overview of method ......................................................................................... -

Deforestation High School Environmental Science Instructional Sequence

District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent of Education Deforestation High School Environmental Science Instructional Sequence 1 This high school environmental science instructional sequence was created to support teaching the Next Generation Science Standards through the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) 5E instructional model. Developed by District of Columbia teachers, these lessons include real-world contexts for learning about environmental science through a lens that encourages student investigation of local issues. The lessons also support Scope and Sequence documents used by District local education agencies: Unit 1: Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy and Dynamics Advisory 1 and 2 Acknowledgements: Charlene Cummings, District of Columbia International School This curriculum resource can be downloaded online: https://osse.dc.gov/service/environmental-literacy-program-elp 2 Overview and Goal of the Lesson: In this sequence of lessons, students will investigate the causes and effects of deforestation and explain ecosystem services. Students will explore their local communities and discuss the ecosystem services that trees can provide. Students will participate in a hyperlocal Meaningful Watershed Educational Experience (MWEE) in which they will complete a tree inventory of their school’s campus. In contrast, students will then shift to focus on predicting causes of deforestation around the world. By researching and exploring personal stories of communities around the world affected by deforestation, students will be able to explain and describe the causes and effects of deforestation. With new learned knowledge, students will participate in a Socratic seminar via the lens of an ambassador from a country that is suffering from deforestation. Finally, to address local issues, students will construct a proposal for where a tree should be planted on their school grounds or in their communities. -

Mississippi Valley Reforestation

naturalcapitalpartners.com USA: Mississippi Valley Reforestation The project aims to reforest one million acres of the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, an important ecosystem in need of conservation, having experienced sustained deforestation in recent decades. Tree planting will reduce an estimated 200 tons CO2 equivalent per acre, while creating revenue for landowners and bringing jobs to the area, as well as improving water quality and biodiversity. Project type: Forestry and landscapes Region: North America Standards: American Carbon Registry Future growth: Aerial shot of the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley forest with four to five month old plantings. © GreenTrees naturalcapitalpartners.com The project The Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley was once covered by 22 million acres of dense © GreenTrees forests but now supports less than 20% of that forest as a result of deforestation. Landowners, who voluntarily enrol in the project, commit to protecting and planting trees on land Landowners, who voluntarily enrol in the that has previously been used for agriculture. project, commit to protecting and planting trees on land that has previously been used for agriculture. In the absence of the project, The project developer received the continued use of the land for crops or pasture 2009 Innovation Award from the Southern would prevent natural regeneration of trees. Growth Policies Board for its unique business model in restoring hardwood forests. Through carbon revenues, economic incentives help encourage landowners The Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley to enrol and lease their land rather than supports less than 20% of its the more typical conservation model of purchasing all the land to place it into original forest due to deforestation easements. -

Overpopulation Is Not the Problem - Nytimes.Com Page 1 of 3

Overpopulation Is Not the Problem - NYTimes.com Page 1 of 3 September 13, 2013 Overpopulation Is Not the Problem By ERLE C. ELLIS BALTIMORE — MANY scientists believe that by transforming the earth’s natural landscapes, we are undermining the very life support systems that sustain us. Like bacteria in a petri dish, our exploding numbers are reaching the limits of a finite planet, with dire consequences. Disaster looms as humans exceed the earth’s natural carrying capacity. Clearly, this could not be sustainable. This is nonsense. Even today, I hear some of my scientific colleagues repeat these and similar claims — often unchallenged. And once, I too believed them. Yet these claims demonstrate a profound misunderstanding of the ecology of human systems. The conditions that sustain humanity are not natural and never have been. Since prehistory, human populations have used technologies and engineered ecosystems to sustain populations well beyond the capabilities of unaltered “natural” ecosystems. The evidence from archaeology is clear. Our predecessors in the genus Homo used social hunting strategies and tools of stone and fire to extract more sustenance from landscapes than would otherwise be possible. And, of course, Homo sapiens went much further, learning over generations, once their preferred big game became rare or extinct, to make use of a far broader spectrum of species. They did this by extracting more nutrients from these species by cooking and grinding them, by propagating the most useful species and by burning woodlands to enhance hunting and foraging success. Even before the last ice age had ended, thousands of years before agriculture, hunter- gatherer societies were well established across the earth and depended increasingly on sophisticated technological strategies to sustain growing populations in landscapes long ago transformed by their ancestors. -

Population Pressure and Land Degradation: the Case of Ethiopia

Poverty, Resource Scarcity and Incentives for Soil and Water Conservation: Analysis of Interactions with a Bio-economic Model Bekele Shiferaw1 International Crops Research Institute for the Semiarid Tropics (ICRISAT) Patancheru 502 324, Andhara Pradesh, India E-mail: [email protected] And Stein Holden Department of Economics and Social Sciences Agricultural University of Norway Contributed paper selected for presentation at the 25th International Conference of Agricultural Economists, August 16-22, 2003, Durban, South Africa Copyright 2003 by Bekele Shiferaw and Stein Holden. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. 1 Corresponding author. 1 Poverty, Resource Scarcity and Incentives for Soil and Water Conservation: Analysis of Interactions with a Bio-economic Model Abstract The paper examines the interlinkages between population pressure and poverty, possible impacts on household welfare and land management, and the consequent pathways of development in a low potential rural economy. A dynamic non-separable bio-economic model, calibrated using data from the Ethiopian highlands, is used to trace key relationships between population pressure, poverty and soil fertility management in smallholder agriculture characterized by high levels of soil degradation. Farm households maximize their discounted utility over the planning horizon. Land, labor and credit markets are imperfect. Hence, production, consumption and investment decisions are jointly determined in each period. The level of soil degradation is endogenous and has feedback effects on the stock and quality of the resource base. This may in turn influence land management choices. Under high population pressure, land becomes dearer relative to labor.