Deforestation and Reforestation Impacts on Soils in the Tropics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reforestation: Likely Working on Certification, an Emerg- Nations Secretary-General’S Climate Ing Concept That Sought to Set Third Summit

18 www.taylorguitars.com [Sustainability] arrived in Washington, D.C. in well over a decade, but in 2014 the 1993 and began my professional concept took a twist when govern- career working in environmental ments, private companies, and civil Ipolitics. Anyone involved with interna- society groups signed the New York tional forest policy in the 1990s was Declaration of Forests at the United Reforestation: likely working on certification, an emerg- Nations Secretary-General’s Climate ing concept that sought to set third Summit. The Declaration is a voluntary, from POLITICS to PLANTING party management standards for active non-legally binding pledge to halve the forestry operations. The idea was (and rate of deforestation by 2020, to end still is) that a consumer would choose a it by 2030, and to restore hundreds With Taylor embarking on reforestation efforts product that had an ecolabel over one of millions of acres of degraded land. that did not, if it assured you that the A year later, in 2015, largely due to in Cameroon and Hawaii, Scott Paul explains the product originated from a well-managed pressure from activist organizations, forest. Think Gifford Pinchot meets the literally hundreds of companies involved politics of forest restoration and why Taylor’s Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. in the Southeast Asian palm oil trade timing might be ideal. The Forest Stewardship Council was announced some sort of new policy. born at this time, and for a decade Looking back at these two events, it’s certification overshadowed much of the fair to say that while lofty words do not global forest policy dialogue. -

Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R

LAND USE, LAND COVER AND SOIL SCIENCES – Vol. V – Desertification and Deforestation in Africa - R. Penny DESERTIFICATION AND DEFORESTATION IN AFRICA R. Penny Environmental and Developmental Consultant/Practitioner, Cape Town, South Africa Keywords: arid, semi-arid, dry sub-humid, drought, drylands, land degradation, land tenure, sustainability Contents 1. Introduction 2. Global Context 3. Land Degradation in Africa Today 3.1. Geographical Regions 3.2. Socio-Economic Aspects 4. Causes and Consequences 4.1. Drought and Other Disasters 4.2. Water Quality and Availability 4.3. Loss of Vegetative Cover 4.4. Loss of Soil Fertility 4.5. Poverty and Population 4.6. Effect of Land Tenure 4.7. Health 5. Combating Desertification 5.1. Past Trends 5.2. Current Attempts to Combat Desertification 5.3. Synergy of the Three Sustainable Development Conventions 5.4. The Role of Science and Technology in Combating Desertification 5.5. Synergy in Environmental Policy Development 6. Future Perspectives: The Way Forward 7. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS Africa is particularly vulnerable to desertification. Two thirds of the continent consists of desert or drylands.SAMPLE The obvious causes of desertificatiCHAPTERSon and deforestation consist of major ecosystem changes, such as land conversion for various purposes, over- dependence on natural resources and several forms of unsustainable land use. However, the issue of desertification is inseparable from social problems such as poverty and land tenure issues. Politics, war and national disasters affect the movements of people and thus impact on the land. International trade policies as well play a part in land management and/or exploitation. -

Road Impact on Deforestation and Jaguar Habitat Loss in The

ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT ROAD IMPACT ON DEFORESTATION AND JAGUAR HABITAT LOSS IN THE MAYAN FOREST by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando University Program in Ecology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Norman L. Christensen, Supervisor ___________________________ Alexander Pfaff ___________________________ Dean L. Urban ___________________________ Randall A. Kramer An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Ecology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyright by Dalia Amor Conde Ovando 2008 Abstract The construction of roads, either as an economic tool or as necessity for the implementation of other infrastructure projects is increasing in the tropical forest worldwide. However, roads are one of the main deforestation drivers in the tropics. In this study we analyzed the impact of road investments on both deforestation and jaguar habitat loss, in the Mayan Forest. As well we used these results to forecast the impact of two road investments planned in the region. Our results show that roads are the single deforestation driver in low developed areas, whether many other drivers play and important role in high developed areas. In the short term, the impact of a road in a low developed area is lower than in a road in a high developed area, which could be the result of the lag effect between road construction and forest colonization. -

Reforestation Forester Work Location: Ukiah, CA

Position Description Position Title: Reforestation Forester Work Location: Ukiah, CA The Mendocino Family of Companies (Mendocino Forest Products Company, Mendocino Redwood Company, Humboldt Redwood Company, Humboldt Sawmill Company, and Allweather Wood), is a leading manufacturer and distributor of environmentally certified redwood, Douglas-fir, and preservative treated lumber products throughout California and the Western U.S. Our culture is based in environmental stewardship and community support. The company maintains Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC® C013133) certification for its forestlands, manufacturing, and distribution operations. Mendocino Redwood Company, LLC (MRC) located in Ukiah, CA is seeking a Reforestation Forester to join our forestry team. This is a full-time position that involves working closely with the Forest Manager for the purpose of meeting forest stewardship and business objectives. Relocation help is available! Summary Direct responsibility for tree planting from inception to free-to-grow status, including all facets of vegetation management and materials sourcing. These activities must 1.) Comply with all applicable state and federal laws; 2.) Produce the desired rate of return on investments; 3.) Be conducted safely, and 4.) Be deployed in a manner that is consistent with the Company’s core values and consistent with the requirements of its Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. Ensuring prompt reforestation and state certification of compliance with required stocking standards is key to achieving sustained yield harvest levels and financial objectives. Duties and Responsibilities To perform this job successfully, an individual must be able to perform each essential duty satisfactorily. The requirements listed below are representative of the knowledge, skill, and/or abilities required. Reasonable accommodations may be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform the essential functions. -

Hidden Deforestation in the Brazil - China Beef and Leather Trade 1

Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade 1 Hidden deforestation in the Brazil - China beef and leather trade Christina MacFarquhar, Alex Morrice, Andre Vasconcelos August 2019 Key points: China is Brazil’s biggest export market for cattle products, • Cattle ranching is the leading direct driver of deforestation which are a major driver of deforestation and other native and other native vegetation clearance in Brazil, and some vegetation loss in Brazil. This brief identifies 43 companies international beef and leather supply chains are linked to worldwide that are highly exposed to deforestation risk through these impacts. the Brazil-China beef and leather trade, and which have significant potential to help reduce this risk. The brief shows • China (including Hong Kong) is Brazil’s biggest importer of which of these companies have published policies to address beef and leather, and many companies linked to this trade are deforestation risk related to these commodities. It also reveals exposed to deforestation risk. the supplier-buyer relationships between these companies, • We identify 43 companies globally that are particularly exposed and how their connections may mean even those buyers with to the deforestation risk associated with the Brazil-China beef commitments to reduce or end deforestation may not be able to and leather trade and have the potential to reduce these risks. meet them. It then makes recommendations for the next steps companies can take to address deforestation risk. • Most of these companies have not yet published sustainable sourcing policies to address this risk. The companies include cattle processors operating in Brazil, processors and manufacturers operating in China, and • Most appear unable to guarantee that their supply chains are manufacturers and retailers headquartered in Europe and the deforestation-free, because they, or a supplier, lack a strong United States of America (US). -

An Investment Primer for Reforestation CARBON REMOVAL, ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL IMPACTS, and FINANCIAL POTENTIAL

1 An Investment Primer for Reforestation CARBON REMOVAL, ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS, AND FINANCIAL POTENTIAL JANUARY 2020 1 CONTENTS Contents About CREO 2 Terms 3 Executive Summary 4 Background Forestry for Climate 6 Reforestation Investment Potential 9 - Investment Avenues 9 - Costs and Returns 10 Carbon Markets Regulatory Compliance 14 Voluntary 15 Corporate Offsetting 15 Summary 16 Timber and Non-Timber Forest Products Timber 18 Agroforestry 19 Summary 20 Restoration and Conservation Initiatives Direct Revenue Creation 22 Blended Finance 23 Catalytic Capital 24 Summary 24 Moving Forward 25 Appendix A: CREO Modelling Assumptions 26 Appendix B: Carbon Markets 27 Citations 28 2 ABOUT CREO About CREO The CREO Syndicate (“CREO”) is a 501c3 public charity founded by wealth owners and family offices with a mission to address the most pressing environmental challenges of our time affecting communities across the globe—climate change and resource scarcity. By catalyzing private capital and scaling innovative solutions, CREO is contributing to protecting and preserving the environment and accelerating the transition to a sustainable economy for the benefit of the public. CREO works closely with a broad set of global stakeholders, including Members (wealth owners, family offices, and family-owned enterprises), Friends (aligned investors such as pension funds), and Partners (government, not-for-profit organizations and academia), who collaboratively develop and invest in solutions across sectors, asset classes and geographies. CREO’s primary activities include 1) knowledge building; 2) relationship building among like-minded, values-aligned, long-term investors; 3) conducting select research to support the advancement of its mission; and 4) deal origination. 3 TERMS Terms Afforestation (AF): Planting and/or deliberate seeding on land not forested over the last 50 years. -

Afforestation and Reforestation - Michael Bredemeier, Achim Dohrenbusch

BIODIVERSITY: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION – Vol. II - Afforestation and Reforestation - Michael Bredemeier, Achim Dohrenbusch AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION Michael Bredemeier Forest Ecosystems Research Center, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany Achim Dohrenbusch Institute for Silviculture, University of Göttingen, Germany Keywords: forest ecosystems, structures, functions, biomass accumulation, biogeochemistry, soil protection, biodiversity, recovery from degradation. Contents 1. Definitions of terms 2. The particular features of forests among terrestrial ecosystems 3. Ecosystem level effects of afforestation and reforestation 4. Effects on biodiversity 5. Arguments for plantations 6. Political goals of afforestation and reforestation 7. Reforestation problems 8. Afforestation on a global scale 9. Planting techniques 10. Case studies of selected regions and countries 10.1. China 10.2. Europe 11. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary Forests are rich in structure and correspondingly in ecological niches; hence they can harbour plentiful biological diversity. On a global scale, the rate of forest loss due to human interference is still very high, currently ca. 10 Mha per year. The loss is highest in the tropics; in some tropical regions rates are alarmingly high and in some virtually all forestUNESCO has been destroyed. In this situat– ion,EOLSS afforestation appears to be the most significant option to counteract the global loss of forest. Plantation of new forests is progressing overSAMPLE an impressive total area wo rldwideCHAPTERS (sum in 2000: 187 Mha; rate ca. 4.5 Mha.a-1), with strong regional differences. Forest plantations seem to have the potential to provide suitable habitat and thus contribute to biodiversity conservation in many situations, particularly in problem areas of the tropics where strong forest loss has occurred. -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

Human Population Growth and Its Implications on the Use and Trends of Land Resources in Migori County, Kenya

HUMAN POPULATION GROWTH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON THE USE AND TRENDS OF LAND RESOURCES IN MIGORI COUNTY, KENYA PAULINE TOLO OGOLA A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Environmental Studies (Agroforestry and Rural Development) in the School of Environmental Studies of Kenyatta University NOVEMBR, 2018 1 DEDICATION To my loving parents, Mr. and Mrs. Ogola, With long life He will satisfy you i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I am grateful to the Man above who gave me strength and health throughout this study. For sure, His goodness and Mercies are new every day. Secondly, I am greatly indebted to my supervisors Dr. Letema and Dr. Obade for their wise counsel and patience. Thirdly, I would like to convey my utmost gratitude to my parents and siblings for their moral support and prayers. Special thanks to my brother Stephen Ogeda for supporting me financially. Finally, I wish to express many thanks to my colleagues at the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development and friends who have offered their support in kind and deed. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION………………………………………………………………………… Error! Bookmark not defined. DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………...i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT……………………………………………………………...ii LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………...vi LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………vii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS……………………………………………….viii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………i x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..1 1.1 Background to the Problem ......................................................................................... -

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

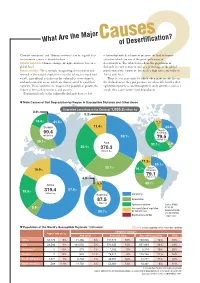

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Ramping up Reforestation in the United States: a Guide for Policymakers March 2021 Cover Photo: CDC Photography / American Forests

Ramping up Reforestation in the United States: A Guide for Policymakers March 2021 Cover photo: CDC Photography / American Forests Executive Summary Ramping Up Reforestation in the United States: A Guide for Policymakers is designed to support the development of reforestation policies and programs. The guide highlights key findings on the state of America’s tree nursery infrastructure and provides a range of strategies for encouraging and enabling nurseries to scale up seedling production. The guide builds on a nationwide reforestation assessment (Fargione et al., 2021) and follow-on assessments (Ramping Up Reforestation in the United States: Regional Summaries companion guide) of seven regions in the contiguous United States (Figure 1). Nursery professionals throughout the country informed our key findings and strategies through a set of structured interviews and a survey. Across the contiguous U.S., there are over 133 million acres of reforestation opportunity on lands that have historically been forested (Cook-Patton et al., 2020). This massive reforestation opportunity equals around 68 billion trees. The majority of opportunities occur on pastureland, including those with poor soils in the Eastern U.S. Additionally, substantial reforestation opportunities in the Western U.S. are driven by large, severe wildfires. Growing awareness of this potential has led governments and organizations to ramp up reforestation to meet ambitious climate and biodiversity goals. Yet, there are many questions about the ability of nurseries to meet the resulting increase in demand for tree seedlings. These include a lack of seed, workforce constraints, and insufficient nursery infrastructure. To meet half of the total reforestation opportunity by 2040 (i.e., 66 million acres) would require America’s nurseries to produce an additional 1.8 billion seedlings each year. -

FAO Forestry Paper 120. Decline and Dieback of Trees and Forests

FAO Decline and diebackdieback FORESTRY of tretreess and forestsforests PAPER 120 A globalgIoia overviewoverview by William M. CieslaCiesla FADFAO Forest Resources DivisionDivision and Edwin DonaubauerDonaubauer Federal Forest Research CentreCentre Vienna, Austria Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 19941994 The designations employedemployed and the presentation of material inin thisthis publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever onon the part ofof thethe FoodFood andand AgricultureAgriculture OrganizationOrganization ofof thethe UnitedUnited Nations concerning the legallega! status ofof anyany country,country, territory,territory, citycity oror area or of itsits authorities,authorities, oror concerningconcerning thethe delimitationdelimitation ofof itsits frontiers or boundarboundaries.ies. M-34M-34 ISBN 92-5-103502-492-5-103502-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publicationpublication may be reproduced,reproduced, stored in aa retrieval system, or transmittedtransmitted inin any form or by any means, electronic, mechani-mechani cal, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyrightownecopyright owner.r. Applications for such permission, withwith aa statement of the purpose andand extentextent ofof the reproduction,reproduction, should bebe addressed toto thethe Director,Director, Publications Division,Division, FoodFood andand Agriculture Organization ofof the United Nations,Nations, VVialeiale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy.Italy. 0© FAO FAO 19941994