Tree-Compatible Ground Covers for Reforestation and Erosion Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reforestation: Likely Working on Certification, an Emerg- Nations Secretary-General’S Climate Ing Concept That Sought to Set Third Summit

18 www.taylorguitars.com [Sustainability] arrived in Washington, D.C. in well over a decade, but in 2014 the 1993 and began my professional concept took a twist when govern- career working in environmental ments, private companies, and civil Ipolitics. Anyone involved with interna- society groups signed the New York tional forest policy in the 1990s was Declaration of Forests at the United Reforestation: likely working on certification, an emerg- Nations Secretary-General’s Climate ing concept that sought to set third Summit. The Declaration is a voluntary, from POLITICS to PLANTING party management standards for active non-legally binding pledge to halve the forestry operations. The idea was (and rate of deforestation by 2020, to end still is) that a consumer would choose a it by 2030, and to restore hundreds With Taylor embarking on reforestation efforts product that had an ecolabel over one of millions of acres of degraded land. that did not, if it assured you that the A year later, in 2015, largely due to in Cameroon and Hawaii, Scott Paul explains the product originated from a well-managed pressure from activist organizations, forest. Think Gifford Pinchot meets the literally hundreds of companies involved politics of forest restoration and why Taylor’s Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. in the Southeast Asian palm oil trade timing might be ideal. The Forest Stewardship Council was announced some sort of new policy. born at this time, and for a decade Looking back at these two events, it’s certification overshadowed much of the fair to say that while lofty words do not global forest policy dialogue. -

Reforestation Forester Work Location: Ukiah, CA

Position Description Position Title: Reforestation Forester Work Location: Ukiah, CA The Mendocino Family of Companies (Mendocino Forest Products Company, Mendocino Redwood Company, Humboldt Redwood Company, Humboldt Sawmill Company, and Allweather Wood), is a leading manufacturer and distributor of environmentally certified redwood, Douglas-fir, and preservative treated lumber products throughout California and the Western U.S. Our culture is based in environmental stewardship and community support. The company maintains Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC® C013133) certification for its forestlands, manufacturing, and distribution operations. Mendocino Redwood Company, LLC (MRC) located in Ukiah, CA is seeking a Reforestation Forester to join our forestry team. This is a full-time position that involves working closely with the Forest Manager for the purpose of meeting forest stewardship and business objectives. Relocation help is available! Summary Direct responsibility for tree planting from inception to free-to-grow status, including all facets of vegetation management and materials sourcing. These activities must 1.) Comply with all applicable state and federal laws; 2.) Produce the desired rate of return on investments; 3.) Be conducted safely, and 4.) Be deployed in a manner that is consistent with the Company’s core values and consistent with the requirements of its Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. Ensuring prompt reforestation and state certification of compliance with required stocking standards is key to achieving sustained yield harvest levels and financial objectives. Duties and Responsibilities To perform this job successfully, an individual must be able to perform each essential duty satisfactorily. The requirements listed below are representative of the knowledge, skill, and/or abilities required. Reasonable accommodations may be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform the essential functions. -

An Investment Primer for Reforestation CARBON REMOVAL, ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL IMPACTS, and FINANCIAL POTENTIAL

1 An Investment Primer for Reforestation CARBON REMOVAL, ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS, AND FINANCIAL POTENTIAL JANUARY 2020 1 CONTENTS Contents About CREO 2 Terms 3 Executive Summary 4 Background Forestry for Climate 6 Reforestation Investment Potential 9 - Investment Avenues 9 - Costs and Returns 10 Carbon Markets Regulatory Compliance 14 Voluntary 15 Corporate Offsetting 15 Summary 16 Timber and Non-Timber Forest Products Timber 18 Agroforestry 19 Summary 20 Restoration and Conservation Initiatives Direct Revenue Creation 22 Blended Finance 23 Catalytic Capital 24 Summary 24 Moving Forward 25 Appendix A: CREO Modelling Assumptions 26 Appendix B: Carbon Markets 27 Citations 28 2 ABOUT CREO About CREO The CREO Syndicate (“CREO”) is a 501c3 public charity founded by wealth owners and family offices with a mission to address the most pressing environmental challenges of our time affecting communities across the globe—climate change and resource scarcity. By catalyzing private capital and scaling innovative solutions, CREO is contributing to protecting and preserving the environment and accelerating the transition to a sustainable economy for the benefit of the public. CREO works closely with a broad set of global stakeholders, including Members (wealth owners, family offices, and family-owned enterprises), Friends (aligned investors such as pension funds), and Partners (government, not-for-profit organizations and academia), who collaboratively develop and invest in solutions across sectors, asset classes and geographies. CREO’s primary activities include 1) knowledge building; 2) relationship building among like-minded, values-aligned, long-term investors; 3) conducting select research to support the advancement of its mission; and 4) deal origination. 3 TERMS Terms Afforestation (AF): Planting and/or deliberate seeding on land not forested over the last 50 years. -

Afforestation and Reforestation - Michael Bredemeier, Achim Dohrenbusch

BIODIVERSITY: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION – Vol. II - Afforestation and Reforestation - Michael Bredemeier, Achim Dohrenbusch AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION Michael Bredemeier Forest Ecosystems Research Center, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany Achim Dohrenbusch Institute for Silviculture, University of Göttingen, Germany Keywords: forest ecosystems, structures, functions, biomass accumulation, biogeochemistry, soil protection, biodiversity, recovery from degradation. Contents 1. Definitions of terms 2. The particular features of forests among terrestrial ecosystems 3. Ecosystem level effects of afforestation and reforestation 4. Effects on biodiversity 5. Arguments for plantations 6. Political goals of afforestation and reforestation 7. Reforestation problems 8. Afforestation on a global scale 9. Planting techniques 10. Case studies of selected regions and countries 10.1. China 10.2. Europe 11. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary Forests are rich in structure and correspondingly in ecological niches; hence they can harbour plentiful biological diversity. On a global scale, the rate of forest loss due to human interference is still very high, currently ca. 10 Mha per year. The loss is highest in the tropics; in some tropical regions rates are alarmingly high and in some virtually all forestUNESCO has been destroyed. In this situat– ion,EOLSS afforestation appears to be the most significant option to counteract the global loss of forest. Plantation of new forests is progressing overSAMPLE an impressive total area wo rldwideCHAPTERS (sum in 2000: 187 Mha; rate ca. 4.5 Mha.a-1), with strong regional differences. Forest plantations seem to have the potential to provide suitable habitat and thus contribute to biodiversity conservation in many situations, particularly in problem areas of the tropics where strong forest loss has occurred. -

Ramping up Reforestation in the United States: a Guide for Policymakers March 2021 Cover Photo: CDC Photography / American Forests

Ramping up Reforestation in the United States: A Guide for Policymakers March 2021 Cover photo: CDC Photography / American Forests Executive Summary Ramping Up Reforestation in the United States: A Guide for Policymakers is designed to support the development of reforestation policies and programs. The guide highlights key findings on the state of America’s tree nursery infrastructure and provides a range of strategies for encouraging and enabling nurseries to scale up seedling production. The guide builds on a nationwide reforestation assessment (Fargione et al., 2021) and follow-on assessments (Ramping Up Reforestation in the United States: Regional Summaries companion guide) of seven regions in the contiguous United States (Figure 1). Nursery professionals throughout the country informed our key findings and strategies through a set of structured interviews and a survey. Across the contiguous U.S., there are over 133 million acres of reforestation opportunity on lands that have historically been forested (Cook-Patton et al., 2020). This massive reforestation opportunity equals around 68 billion trees. The majority of opportunities occur on pastureland, including those with poor soils in the Eastern U.S. Additionally, substantial reforestation opportunities in the Western U.S. are driven by large, severe wildfires. Growing awareness of this potential has led governments and organizations to ramp up reforestation to meet ambitious climate and biodiversity goals. Yet, there are many questions about the ability of nurseries to meet the resulting increase in demand for tree seedlings. These include a lack of seed, workforce constraints, and insufficient nursery infrastructure. To meet half of the total reforestation opportunity by 2040 (i.e., 66 million acres) would require America’s nurseries to produce an additional 1.8 billion seedlings each year. -

FAO Forestry Paper 120. Decline and Dieback of Trees and Forests

FAO Decline and diebackdieback FORESTRY of tretreess and forestsforests PAPER 120 A globalgIoia overviewoverview by William M. CieslaCiesla FADFAO Forest Resources DivisionDivision and Edwin DonaubauerDonaubauer Federal Forest Research CentreCentre Vienna, Austria Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 19941994 The designations employedemployed and the presentation of material inin thisthis publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever onon the part ofof thethe FoodFood andand AgricultureAgriculture OrganizationOrganization ofof thethe UnitedUnited Nations concerning the legallega! status ofof anyany country,country, territory,territory, citycity oror area or of itsits authorities,authorities, oror concerningconcerning thethe delimitationdelimitation ofof itsits frontiers or boundarboundaries.ies. M-34M-34 ISBN 92-5-103502-492-5-103502-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publicationpublication may be reproduced,reproduced, stored in aa retrieval system, or transmittedtransmitted inin any form or by any means, electronic, mechani-mechani cal, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyrightownecopyright owner.r. Applications for such permission, withwith aa statement of the purpose andand extentextent ofof the reproduction,reproduction, should bebe addressed toto thethe Director,Director, Publications Division,Division, FoodFood andand Agriculture Organization ofof the United Nations,Nations, VVialeiale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy.Italy. 0© FAO FAO 19941994 -

Afforestation and Reforestation for Climate

IUCN Programme Office for Central Europe Afforestation and Reforestation for Climate Change Mitigation: Potentials for Pan-European Action Afforestation and Reforestation for Climate Change Mitigation: Potentials for Pan-European Action Warsaw, July 2004 Published by: IUCN Programme Office for Central Europe Copyright: (2004) IUCN – The World Conservation Union and Foundation IUCN Poland (IUCN Programme Office for Central Europe) The background research for this policy brief was carried out by Dr. Christoph Wildburger. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without permission from the copyright holder. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. ISBN: 2-8317-0723-4 Cover photo: Sławomir Janyszek Photos in the text: Sławomir Janyszek, Marcin Karetta, Magdalena Kłosowska Lay out and cover design by: Carta Blanca, Ewa Cwalina Produced with support of the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV). Afforestation and reforestation activities enjoy high attention at the policy agenda as measures for carbon sequestration in order to mitigate climate change. The decrease of agricultural viability and the objective to increase forest cover in order to ensure soil protection, the supply with forest products and a reduction of forest fragmentation also trigger afforestation of former agricultural land in certain areas in Europe. But the establishment of new forested areas can endanger other environmental and social services, including biological diversity. Therefore, there is a need for a comprehensive approach to afforestation and reforestation, which should consider carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, soil protection, as well as sustainable provision of raw material for forest industries and other goods and services in a balanced way. -

Warden and Woodsman

SD 12. / Ly,ryva/T1 [xT^tr^ ' 14 I RHODE ISLAND DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY. Warden and Woodsman. BY JESSE B. MOWRY Commissioner of Forestry* PROVIDENCE, R. I. E. L. KREEMAN COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS. 1913. RHODE ISLAND, ; DEPARTMENT .OF FORESTRY. WARDEN AND WOODSMAN. JESSE B. MOWRY, Commissioner of Forestry. PROVIDENCE, R. I. K. L. FREEMAN COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS. 1913. .R FOREWORD. Since progress in practical forestry depends much upon mutual understanding and assistance between the wardens, woodsmen, and timber owners, the aim in this pamphlet is to combine instructions to forest wardens with a brief outline of the best methods of cutting the timber of this region. The Author. Chepachet, November, 1913. MAR 28 W* PART L INSTRUCTIONS TO FOREST WARDENS. 1. The prevention of forest fires being a service of great value to the state, do not hesitate to do your full duty under the law, feel- ing assured in the discharge of your official duties of the support of all good citizens. 2. Read carefully the forest fire laws, which for convenience, are published in a booklet issued by this office. In reading the law you will observe that there are no restrictions whatever upon the setting of fires in the open air between December 1 and March 1. Between these two dates fires may be set anywhere without a permit from the warden. From March 1 to December 1 fires can be set without a permit, in plowed fields and gardens, and on other land devoid of inflammable materials, and on highways by owners of adjacent lands, etc. -

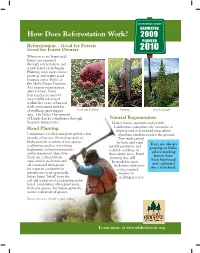

How Does Reforestation Work?

How Does Reforestation Work? Reforestation – Good for Forests Good for Forest Owners When trees are harvested, forests are renewed through reforestation and a new forest cycle begins. Planting trees keeps forests growing and makes good business sense. Rules of the Idaho Forest Practices Act require reforestation after harvest. Every harvested acre must be successfully reforested within five years of harvest with a minimum number of seedlings growing per Seeds and Seedlings Planting 8 years growth acre. The Idaho Department of Lands checks compliance through Natural Regeneration frequent inspections. Idaho’s forests are fertile and prolific. Landowners sometimes rely on nature to Hand Planting disperse seed in harvested areas where Landowners usually hand plant within a few abundant sunshine reaches the ground. months of harvest. Several nurseries in Tree seeds carried Idaho provide a variety of tree species by birds and wind Trees are always as planting stock to serve forest quickly germinate and landowners’ reforestation needs growing in Idaho establish seedlings in where working and management objectives. these sunny areas. Hand Seeds are collected from forests have planting may still been harvested areas similar in climate and be needed to meet elevation and then grown and replanted landowner objectives since statehood. for a year in containers in or the required greenhouses or in open fields number of before being “lifted” from the seedlings per acre. soil and transported for planting in the forest. Landowners often plant more than one species, but nature generally assures a diversity of species. Planters often use a “hoedad” to plant seedlings. Learn more at www.idahoforests.org. -

And Advancement Program

1 I . DOCU COLLEC1 4-H Forestry Project OFEC COLLEC1 and Advancement Program Club Series 1-4 May 1962 . Na me______________ Address____________ School or community County Club leader_________ Name of club_______ Cooperative Extension Service Oregon State University, Corvallis Oregon 4-H Forestry Project What do you do in a 4-H Forestry project? Each year you must do the following: 1. Take at least three hikes into the woods to study trees, other forest plants, and wildlife. Find and identify at least 10 forest items on each hike. (Use pocket guide.) 2. Learn to identify at least 10 new trees or forest plants. Observe 5 or more different kinds of native birds, animals, fish, or reptiles Be able to describe them. Tell what they eat, where they nest or have their young, how they spend the winter, and. how they fit into the life of the forest 4-. Learn at least 10 new "woods words." Know their meaning and how to spell them 5. Participate in your clubts activities. S a. Attend club meetings regularly and be on time. You may be dropped from the club if you have two consecutive or a total of three unexcused absences.Be sure to call your leader and get excused if you cannot attend. b. Individual members (those not in a 4--H club) must complete a step in the advancement program each year until they have completed three steps (or equivalent). 6. Advance as far as you can in the Forestry Advancement program. 7. Write a story of your experiences as a 4-H forestry club member on "My Li_H Story" form, 8. -

Tree Planting and Reforestation in Climate a Community: & Energy 1

understanding climate Tree Planting & & energy Reforestration PURPOSE To promote the planting of trees and forests. Planting trees improves air quality and absorbs carbon from the atmosphere, provides shade, cooling and water management benefits as well as improving quality of life through beautiful public places and increased community valuation. HOW IT WORKS Planting trees and reforesting is a simple way to mitigate climate change while improving quality of life within a community. Areas with more trees see increased economic, social and environmental benefits. According to the Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, these benefits include decreased energy costs due to shading as well as improved air quality for residents. More trees are shown to increase revenue from tourism related to fall foliage viewing, as well as raise property values and revenue through taxes by 7-10%. Moreover, plantings can reduce storm water runoff and decrease the likelihood of flooding. Fruit and nut bearing trees can also provide food to communities while beautifying the city streets. PIONEER VALLEY SUSTAINABILITY TOOLKIT 1 There are different ways to promote tree planting and reforestation in climate a community: & energy 1. Urban and Community Forestry Program: Creating a municipal forestry department with management plans and professional staff is a strong way to encourage tree planting. These groups aim to improve their local environments and enhance livability of communities by protecting, growing and managing community trees and forests. The overall management plan should focus on caring for mature trees, creating planting programs and conserving the overall canopy as well as using the staff and funding to educate the public about the importance of trees in their community. -

Deforestation and Reforestation Impacts on Soils in the Tropics

REVIEWS Deforestation and reforestation impacts on soils in the tropics Edzo Veldkamp 1 ✉ , Marcus Schmidt 1, Jennifer S. Powers2,3 and Marife D. Corre1 Abstract | Soils under natural, tropical forests provide essential ecosystem services that have been shaped by long- term soil–vegetation feedbacks. However, deforestation of tropical forest, with a net rate of 5.5 million hectares annually in 2010–2015, profoundly impacts soil properties and functions. Reforestation is also prominent in the tropics, again altering the state and functioning of the underlying soils. In this Review, we discuss the substantial changes in dynamic soil properties following deforestation and during reforestation. Changes associated with deforestation continue for decades after forest clearing eventually extend to deep subsoils and strongly affect soil functions, including nutrient storage and recycling, carbon storage and greenhouse gas emissions, erosion resistance and water storage, drainage and filtration. Reforestation reverses many of the effects of deforestation, mainly in the topsoil, but such restoration can take decades and the resulting soil properties still deviate from those under natural forests. Improved management of soil organic matter in converted land uses can moderate or reduce the ecologically deleterious effects of deforestation on soils. We emphasize the importance of soil knowledge not only in cross-disciplinary research on deforestation and reforestation but also in developing effective incentives and policies to reduce deforestation.