A Project for Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

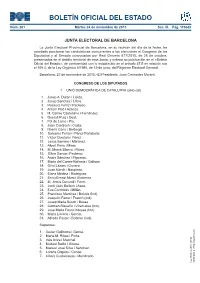

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

«Este Es Un Daño Directo Del Independentismo»

EL MUNDO. MARTES 21 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 43 ECONOMÍA i culo 155 en Cataluña es lo que ha impedido que Barcelona terminara DINERO como sede de la EMA. En un men- FRESCO saje en Twitter, calificó de «éxito del 155» que la capital catalana hubiera CARLOS sido eliminada de la carrera. Puigdemont recordó que hasta SEGOVIA el pasado 1 de octubre, fecha del referéndum ilegal, Barcelona «era España no da la favorita» para acoger este orga- nismo europeo. «Con violencia, re- una en la UE troceso democrático y el 155, el Estado la ha sentenciado», conclu- yó el ex mandatario autonómico. Los gobiernos de la UE decidieron En la misma línea se pronunció que no sólo Ámsterdam y Milán, si- el portavoz parlamentario del PDe- no incluso Copenhague –que está CAT, Carles Campuzano, quien fuera del euro– y Bratislava –cuyo afirmó que el Gobierno «no ha es- mejor aeropuerto es el de Viena– tado a la altura». eran candidatas más válidas que En un comentario publicado en Barcelona. La Ciudad Condal, que su cuenta personal de Twitter, el in- ofrecía la Torre Agbar como sede y dependentista catalán asume que el apoyo de una de las más sólidas no ganar la sede de la EMA es, «sin agencias estatales del medicamento duda, una mala noticia», si bien re- como no pasó de primera ronda, lo calca que «ni Cataluña ni Barcelo- que puede calificarse de humillación. na son quienes han fallado». A su Culpar de este fiasco totalmente al juicio, es el Gobierno quien «no ha Gobierno central como ha hecho el estado a la altura» y recuerda que ya ex presidente de la Generalitat, el Ejecutivo del PP es el principal Carles Puigdemont o parcialmente responsable ante la UE. -

International Renewable Energy Entrepreneurship; a Mixed-Method

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en International Renewable Energy Entrepreneurship; A Mixed- Method Approach By Seyed Meysam Zolfaghari Ejlal Manesh SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND MANAGEMENT AT THE AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF BARCELONA (UAB) © MEYSAM ZOLFAGHARI .All rights reserved. Advisors: Dr. Alex Rialp Prof. Joaquim Vergés Barcelona November 2016 1 Abstract The demand for energy is increasing over time because of the rapid expansion of the global economy and population growth. However, conventional energy systems based on fossil fuels are not only an unreliable source of energy for the future but also cause a range of environmental consequences, including acidification, air pollution, global climate change, etc. Energy-based economic development (EBED) (Carley, Lawrence, Brown, Nourafshan, & Benami, 2011) and sustainable development (SD) (Hopwood, Mellor, & O’Brien, 2005) will consequently require a new source of energy based on renewable energies, which are more accessible, environmentally friendly, secure, and efficient. To address challenges associated with fossil fuels and fostering sustainable development, recent progress in the field of entrepreneurship has shown increased interest in sustainability issues and environmentally friendly technological development. -

The Spanish Gay and Lesbian Movement in Comparative

Instituto Juan March Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales (CEACS) Juan March Institute Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences (CEACS) Pursuing membership in the polity : the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, 1970-1997 Author(s): Calvo, Kerman Year: 2005 Type Thesis (doctoral) University: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales, University of Essex, 2004. City: Madrid Number of pages: ix, 298 p. Abstract: El título de la tesis de Kerman Calvo Borobia es Pursuing membership in the polity: the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, (1970–1997). Lo que el estudio aborda es por qué determinados movimientos sociales varían sus estrategias ante la participación institucional. Es decir, por qué pasan de rechazar la actuación dentro del sistema político a aceptarlo. ¿Depende ello del contexto político y de cambios sociales? ¿Depende de razones debidas al propio movimiento? La explicación principal radica en las percepciones políticas y los mapas intelectuales de los activistas, en las variaciones de estas percepciones a lo largo del tiempo según distintas experiencias de socialización. Atribuye por el contrario menor importancia a las oportunidades políticas, a factores exógenos al propio movimiento, al explicar los cambios en las estrategias de éste. La tesis analiza la evolución en el movimiento de gays y de lesbianas en España desde una perspectiva comparada, a partir de su nacimiento en los años 70 hasta final del siglo, con un importante cambio hacia una estrategia de incorporación institucional a finales de los años 80. La tesis fue dirigida por la profesora Yasemin Soysal, miembro del Consejo Científico, y fue defendida en la Universidad de Essex. -

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos Polvos Trajeron Estos Lodos. Diálogos Postelectorales Diciembre De 2019

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos polvos trajeron estos lodos. Diálogos postelectorales Diciembre de 2019. La preocupación sobre el crecimiento de Vox dio lugar a un diálogo, a vuelapluma y poco sistemático, entre Julio Loras, biólogo y Alber Fabà, sociolingüista. Esas reflexiones se publicaron en Pensamiento crítico en su edición de enero. Ahora siguen dialogando, pero en este caso sobre el resultado de las últimas elecciones generales, la reacción en Catalunya a la sentencia del procés o la posibilidad de un gobierno de coalición que, en el momento en que se han redactado estas notas, aún no ha cuajado, a consecuencia de las dudas sobre la abstención (o no) de ERC en la investidura. ALBERT. Durante los últimos meses me acuerdo a menudo de Borgen, la serie de ficción en la cual tiene un notable protagonismo Kasper Juul, responsable de prensa de Birgitte Nyborg, primera ministra de Dinamarca. ¿Conoces la saga? JULIO. Hace mucho tiempo que no veo ni cine ni series. Llegaron a aburrirme. Por lo general, veía desde el principio por dónde iban a ir los tiros y perdían todo aliciente para mí. Aunque tengo algo de idea sobre esa serie por los medios. Creo que va de asesores de los políticos. ¿No es así? A. Exacto. Me viene al pelo, por eso del papel que parece que ha tenido Ivan Redondo en las decisiones que se han tomado en el PSOE, des de la moción de censura a Rajoy hasta ahora. Redondo es un típico asesor “profesional”. Que yo sepa, asesoró al candidato del PP en las municipales de Badalona en 2011. -

Sin Título-2

NACIONAL P12 NACIONAL P8 El TSJC suspèn la Calvo exclou creació de tres el dret a noves delegacions decidir de la a l’exterior negociació d’investidura El conseller Alfred Bosch ho troba inacceptable i anuncia Primera trobada, avui, DEMÀ amb El Punt Avui que hi presentaran recurs entre el PSOE i ERC 109004-1219487L 1,20€ Edició de Girona DIJOUS · 28 de novembre del 2019. Any XLIV. Núm. 15194 - AVUI / Any XLI. Núm. 14064 - EL PUNT P6,7 Aval del PP i Cs al 155 digital del PSOE DECRET · COP · Aproven la ‘cibercensura’ Podem recula i s’absté El conseller Puigneró diu en nom de “l’ordre públic” al crit de que el decret de Sánchez declara “la república no existeix, idiota” en la ratificació final “l’estat d’excepció digital” L’ESPORTIU Girona P26 L’antiga UNED, la Casa de Cultura municipal Figueres P28 Pressupost ajornat a causa de les escombraries 122454-1201332Q Suárez i Messi van obrir el marcador i Griezmann va rematar la feina amb el tercer gol ■ E. FONTCUBERTA/EFE Victòria del Barça i Triomf de prestigi bitllet per als vuitens europeu de l’Uni jamargant - 28/11/2019 08:04 - 79.155.44.80 FIGUERES tomba la compra del pis on PRENSA IBÉRICA supera els 3,3 MOTXILLA ANTIROBATORI La més segura del mercat, amb cremalleres ocultes, que va viure Salvador Dalí de jove 18 milions de lectors, segons l’EGM 48 també disposa de port USB i connector per a auriculars www.diaridegirona.cat TEL ` 972 20 20 66 | FAX 972 20 20 05 | A/E [email protected] | ADREÇA PASSEIG GENERAL MENDOZA, 2. -

Nacional Contra Un Encara No S’Havien Practi- Ciutadà Europeu Si Ja Han Cat Totes Les Diligències Estat Jutjats Els Fets Pels Demanades, Tal Com Va Quals Se’L Reclama

4 EL PUNT AVUI | DIJOUS, 13 DE MAIG DEL 2021 Transmissió Nous contagis Llits d’UCI 0,85 1.215 423 Nacional Dada anterior: 0,85 Dada anterior: 792 Dada anterior: 442 Els nous contagiats per L’indicador hauria Les UCI haurien d’acollir COVID-19 cada positiu no han de d’estar en 1.000 un màxim de 300 malalts superar l’1 contagis/dia greus POLÍTICA LA FORMACIÓ DEL NOU GOVERN Les delegacions d’ERC, Junts i la CUP sortint plegades ahir de la reunió al Parlament, on van contraure el Segona compromís implícit de donar una segona oportunitat a un acord oportunitat independentista ■ BERNAT VILARÓ / ACN ‘RESET’ La CUP arrenca d’ERC i Junts la promesa d’intentar de nou un acord prenent com a base els punts de consens independentistes VIES Es comprometen a “assolir” un espai per al debat estratègic i a buscar l’autodeterminació i l’amnistia “la pròxima legislatura” Òscar Palau me sobre el que vol fer en reunir ahir a la tarda el sectorials pel programa BARCELONA aquesta legislatura, i que grup parlamentari per fer que ahir van continuar de es comprometen a fer ser- una actualització de l’estat manera discreta. “Només Després de la tempesta ar- vir de base “per desenca- de les converses, “com ja si Junts ens dona els 32 riba la calma, tot i que el re- llar-ne” l’inici. El docu- s’ha fet altres vegades”, re- vots deixarem de depen- frany no diu què passa l’en- ment, redactat amb una lativitzaven fonts consul- dre dels comuns”, recorda- demà de l’endemà. -

Palau De La Musica Catalana De Barcelona 36

Taula de contingut CITES 7 La Vanguardia - Catalán - 21/01/2018 "El ideal de justicia" con Javier del Pino, José Martí Gómez, José Mª Mena, José Mª Fernández Seijo y 8 Mateo Seguí que junto a Lourdes Lancho comentan la sentencia del Caso Palau que se dio a conocer .... Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 21/01/2018 Ana Pastor, Javier Maroto, Juan Carlos Girauta, Carles Campuzano, Óscar Puente, Joan Tardá y Pablo 10 Echenique debaten sobre la corrupción política que afecta a partidos como el PP o CDC. LA SEXTA - EL OBJETIVO - 21/01/2018 Javier del Pino, Quique Peinado, Antonio Castelo y David Navarro comentan en clave de humor noticias 12 de la semana: caso Palau, trama Púnica, rama valenciana de la Gürtel, etc. Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 20/01/2018 Entrevista a Mónica Oltra, vicepresidenta de la Generalitat Valenciana, para hablar de asuntos como los 13 recortes del gobierno, las pensiones, la corrupción en el PP y en la antigua Convergéncia o la .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 16 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre la corrupción política, especialmente los casos juzgados esta .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 19 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre el caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y el periodista Carlos Quílez analizan el caso de corrupción en Cataluña relacionado con el 21 caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua Convergència. -

Preses I Presos Bascos Al País Basc

Drets humans. Solucions. Pau. Preses i presos bascos al País Basc. Deixant enrere un conflicte que s’ha allargat massa, tant en temps com en patiment, al País Basc s’han obert noves oportunitats per construir un escenari de pau. Les converses i els acords adoptats entre diferents agents del País Basc, l’alto-el-foc d’ETA i la implicació i ajuda de la comunitat internacional, han obert el camí per solucionar el conflicte basc. Aquest ha deixat conseqüències de tot tipus i totes han de ser solucionades. Per avançar-hi, cal posar atenció també a la situació dels i les ciutadanes que a causa del conflicte estan empresonades o a l’exili, dispersats a centenars de quilometres del País Basc, amb el patiment afegit que suposa tant per a ells i elles com per als seus familiars. Com a primer pas, doncs, creiem que cal respectar els drets humans bàsics dels presos i preses basques. Respecte que comporta: · Traslladar al País Basc a tots el presos i preses bascos. · Alliberar els presos i preses amb malalties greus. · Acabar amb la prolongació de les condemnes i derogar les mesures que comporten la cadena perpètua. · Respectar tots els drets humans que els corresponen com a presos i com a persones. Per tal de reclamar als estats espanyol i francès que facin passos cap a una solució democràtica, les persones sotasignants subscrivim aquestes reivindicacions amb l’esperit d’impulsar-les des de Catalunya. I, alhora, donem suport a la mobilització del proper 12 de gener a Bilbao, convocada p e r Herrira -plataforma en defensa dels drets dels presos bascos-, amb l’adhesió d’un ampli suport social, així com de nombroses personalitats de la cultura, l’esport i la política basca. -

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports The Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain SIPRI Policy Paper No. 21 Mark Bromley Stockholm International Peace Research Institute May 2008 © SIPRI, 2008 ISSN 1652-0432 (print) ISSN 1653-7548 (online) Printed in Sweden by CM Gruppen, Bromma Contents Contents iii Preface iv Abbreviations v 1. Introduction 1 2. EU engagement in arms export policies 5 The origins of the EU Code of Conduct 5 The development of the EU Code of Conduct since 1998 9 The impact on the framework of member states’ arms export policies 11 The impact on the process of member states’ arms export policies 12 The impact on the outcomes of member states’ arms export policies 13 Box 2.1. Non-EU multilateral efforts in the field of arms export policies 6 3. Case study: the Czech Republic 17 The Czech Republic’s engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 17 The impact on the framework of Czech arms export policy 19 The impact on the process of Czech arms export policy 21 The impact on the outcomes of Czech arms export policy 24 Box 3.1. Key Czech legislation on arms export controls 18 Table 3.1. Czech exports of military equipment, 1997–2006 24 4. Case study: the Netherlands 29 The Netherlands’ engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 29 The impact on the framework of Dutch arms export policy 31 The impact on the process of Dutch arms export policy 32 The impact on the outcomes of Dutch arms export policy 34 Box 4.1. -

Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica, S.A. and Subsidiaries Composing the GAMESA Group

Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica, S.A. and Subsidiaries composing the GAMESA Group Auditors’ Report Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2011 prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards Consolidated Directors' Report Translation of a report originally issued in Spanish based on our work performed in accordance with the audit regulations in force in Spain and of consolidated financial statements originally issued in Spanish and prepared in accordance with the regulatory financial reporting framework applicable to the Group (see Notes 2 and 36). In the event of a discrepancy, the Spanish-language version prevails. Auditor’s report on consolidated annual accounts This version of our report is a free translation of the original, which was prepared in Spanish. All possible care has been taken to ensure that the translation is an accurate representation of the original. However, in all matters of interpretation of information, views or opinions, the original language version of our report takes precedence over this translation To the Shareholders of Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica, S.A. We have audited the consolidated annual accounts of Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica, S.A. (Parent Company) and its subsidiaries (the Group), consisting of the consolidated balance sheet at 31 December 2011, the consolidated income statement, the consolidated statement of comprehensive income, the consolidated statement of changes in equity, the consolidated cash flow statement and related notes to the consolidated annual accounts for the year then ended. As explained in Note 2.a, the Directors of the Parent Company are responsible for the preparation of these consolidated annual accounts in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards as endorsed by the European Union, and other provisions of the financial reporting framework applicable to the Group. -

BUTLLETÍ MUNICIPAL Ajuntament De Bordils Número 30 Desembre 2019

BUTLLETÍ MUNICIPAL Ajuntament de Bordils Número 30 desembre 2019 Vista panoràmica des d’on es poden veure els nous espais: parc dels Horts, passatge de vianants i un tram de muralla - Foto: Xevi Planas 1 ÍNDEX TELÈFONS D’INTERÈS SALUTACIÓ 3 ACTES RESUMIDES DELS PLENS 4 INFORMACIÓ MUNICIPAL 22 OPINIÓ DELS GRUPS MUNICIPALS 24 COMPROMESOS AMB EL MEDI 26 MILLORES I MANTENIMENT 28 RECOMANACIONS DE SALUT 31 ACTIVITATS DE BORDILS 32 RECULL D’ACTIVITATS FETES 36 PER A MÉS INFORMACIÓ MUNICIPAL: La nostra pàgina web: www.bordils.cat El nostre correu electrònic: [email protected] Ajuntament de Bordils @aBordils @ajuntamentdebordils 2 SALUTACIÓ Benvolguts veïns i veïnes, valorar la qualitat de vida que s’ofereix en el nos- tre poble, i els passos que a poc a poc, anem Una vegada més, ja tenim una nova edició del fent com a comunitat. També és una motivació Butlletí Municipal. Fa 5 mesos que vam ence- per afrontar el nou any i platejar-nos la millor tar la legislatura amb un nou equip de govern i manera per atendre els serveis propis de l’Ajun- volem aprofitar aquestes línies per agrair-vos la tament, per vetllar pels compromisos adquirits i confiança rebuda i les mostres de suport rebu- per resoldre les noves situacions que sorgeixen des al llarg d’aquests mesos. en el transcurs del temps. Per a nosaltres, el butlletí municipal és un molt Tot el que es fa no tindria sentit si vosaltres no bon canal de comunicació per fer-vos saber hi fóssiu, i us volem continuar animant que par- les decisions que es van prenent en els plens, ticipeu de les propostes municipals perquè tro- així com també per donar-vos comptes de les bem junts millores que puguem oferir al nostre diferents tasques que es portem a terme, ex- poble.