Genetic Relationships Among Local Vitis Vinifera Cultivars from Campania (Italy)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

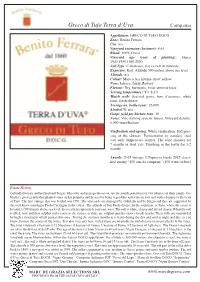

Greco Di Tufo Terra D'uva

Greco di Tufo Terra d’Uva Campania Appellation: GRECO DI TUFO DOCG Zone: Benito Ferrara Cru: n/a Vineyard extension (hectares): 4.65 Blend: 100% Greco Vineyard age (year of planting): Greco 1940,1950,1960,2000 Soil Type: Calcareous, clayey rich in minerals Exposure: East. Altitude 500 meters above sea level Altitude: n/a Colour: More o less intense straw yellow Nose: Intense, fruity, fowery Flavour: Dry, harmonic, bitter almond notes Serving temperature (°C): 8-10 Match with: Seafood pasta, hors d’oeuvres, white meat, fresh cheese Average no. bottles/year: 26,000 Alcohol %: n/a Grape yield per hectare tons: 10 Notes: Vine training system: Guyot. Vineyard density: 6,000 vines/hectare Vinifcation and ageing: White vinifcation. Soft pres- sing of the clusters. Fermentation in stainless steel vats with temperature control. The wine matures for 7 months in steel vats. Finishing in the bottle for 1-2 months Awards: 2015 vintage: L’Espresso Guide 2017 classi- fed among “100 vini da comprare” (100 wines to buy) Estate History Gabriella Ferrara and her husband Sergio, who own and manage the estate, are the fourth generation of viticulturists of their family. Ga- briella’s great grandfather planted vines on his property and he used to bring vegetables and wine on foot and with a donkey to the town of Tufo. The frst vintage that was bottled was 1991. The vineyards are managed by Gabriella and by Sergio and they are supported by the well know oenologist Paolo Caciorgna in the cellar. The altitude of San Paolo district, in the commune of Tufo, where the estate is located, is 500 meters above sea level, the excellent exposure is east/east-west. -

DRAFT Baird Cool Breeze Pilsner, 5.5% Abv – Numazu, Japan 16Oz 10 Perennial Suburban Beverage, Gose, 4.2% Abv - St

DRAFT Baird Cool Breeze Pilsner, 5.5% abv – Numazu, Japan 16oz 10 Perennial Suburban Beverage, Gose, 4.2% abv - St. Louis, Missouri 16 oz 10 Crux Cast Out IPA, 7.6% abv – Bend, Oregon 16oz 9 NV Allimant-Laugner Crémant d’Alsace Rosé Pinot Noir - Alsace, France 11 / 43 NV Pierre Gimonnet Brut Extra Champagne 1Cru Blanc de Blanc Chardonnay - Epernay, France 19 / 64 NV Pierre Moncuit Champagne Grand Cru Blanc de Blanc Chardonnay – Cote des Blanc, France 39 375ML NV Ferrari Trento DOC Brut, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir - Trento, Italy 24 375ML LOCAL LOVE Flight of Local Producers 19 2oz each 2016 Margins Wilson Vineyards Block 20 Chenin Blanc - Clarksburg 12 / 46 2016 Sante Arcangeli “Integrato Barrel Selections” Pinot Noir - Santa Cruz Mountains 15 / 49 2015 Ridge Vineyards “Lytton Estate” Petite Sirah– Sonoma 18 / 57 2016CRU Santedu BEAUJOLAIS Arcangeli “Integrato Barrel Selections” Pinot Noir - Santa Cruz Mountains 15 / 49 2016 La Soeur Cadette Juliénas Gamay –Beaujolais, France 13 / 50 2015 Domain Du Penlois “Sous L’aile du Moulin” Moulin-A-Vent Gamay -Beaujolais, France 12 / 46 2015 Claire et Fabian Chasselay Morgon Gamay –Beaujolais, France 13 / 49 2017 Domaine de la Mordorée – Grenache, Syrah – Côtes du Rhône, France 12 / 39 2017 Marisa Cuomo Costa d’Amalfi – Piedirosso/Aglianico - Furore, Italy 16/ 44 2016 Nikolaihof Zwickl Grüner Veltliner - Wachau, Austria 16 / 48 Liter 2017 Domaine Daulny Sancerre Sauvignon Blanc - Loire, France 12 / 44 2001 C.H. Berres Erdener Treppchen Spätlese Riesling - Mosel, Germany 12 / 42 2014 Domaine Faiveley -

Wines by the Glass

WINES BY THE GLASS BUBBLES PINOT NOIR-Chardonnay, Pierre Paillard, 'Les Parcelles,' Grand Cru, Bouzy, Champagne, France, Extra Brut NV………………………….22 a family operation with prime placement in the Montagne de Reims produces this fresh, zippy farmer fizz CHENIN BLANC, Domaine du Facteur, Vouvray, Loire, France, Extra Brut NV…………………………………...……………………………………………….....13 "the postman" is the playful side of a 5th generation estate and this wine delivers frothy fruit with a racy finish ROSÉ of PINOT NOIR, Val de Mer, 'French Sparkling,' France, Brut NV……………………………………………………………………14 Patrick Piuze, an "it" guy of Chablis, offers up these beautifully blush bubbles WHITE TIMORASSO, Vigneti Massa, 'Terra: Petit Derthona,' Colli Tortonesi, Piedmont, Italy 2016………………………………….13 young vines from Walter's vineyards planted to a grape he saved from obscurity - a don't-wait version of his ageable cult favorite GRÜNER VELTLINER, Nigl, 'Freiheit,' Kremstal, Austria 2017…………………………………………………………………….……. 11 we welcome spring's flavors as an ideal pairing with a glass of this; crunchy and peppery in all the right ways SAUVIGNON BLANC, Domaine La Croix Saint-Laurent, Sancerre, Loire, France 2017……………………………………………………………………………13 a family estate planted on prime terres blanches soil, the Cirottes bottle energetic, pure examples of their region CHENIN BLANC, Pierre Bise, 'Clos de Coulaine,' Savennieres, Loire, France 2015…………………………….……………….. 14 nerd alert! wine geeks rejoice! everyone else don't mind them - it's chenin, it's delicious, drink up! CHARDONNAY, Enfield Wine Co., -

Italian Wine Regions Dante Wine List

ITALIAN WINE REGIONS DANTE WINE LIST: the wine list at dante is omaha's only all italian wine list. we are also feature wines from each region of italy. each region has its own unique characteristics that make the wines & grapes distinctly unique and different from any other region of italy. as you read through our selections, you will first have our table wines, followed by wines offered by the glass & bottle, then each region with the bottle sections after that. below is a little terminology to help you with your selections: Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita or D.O.C.G. - highest quality level of wine in italy. wines produced are of the highest standards with quantiy & quality control. 74 D.O.C.G.'s exist currently. Denominazione di Origine Controllata or D.O.C. - second highest standards in italian wine making. grapes & wines are made with standards of a high level, but not as high a level as the D.O.C.G. 333 D.O.C.'s exist currently. Denominazione di Origine Protetta or D.O.P.- European Union law allows Italian producers to continue to use these terms, but the EU officially considers both to be at the same level of Protected Designation of Origin or PDO—known in Italy as Denominazione di Origine Protetta or DOP. Therefore, the DOP list below contains all 407 D.O.C.'s and D.O.C.G.'s together Indicazione Geografica Tipica or I.G.T. - wines made with non tradition grapes & methods. quality level is still high, but gives wine makers more leeway on wines that they produce. -

Mastro Greco Campania IGT- Winebow

Mastro Greco Campania IGT 2017 W I N E D E S C R I P T I O N Made from 100% Greco grapes, this wine is fermented in stainless steel tanks under controlled temperatures. A B O U T T H E V I N E Y A R D The estates for the production of the Mastro Greco are located mainly on clay soils with a South-East exposure at 350 m a.s.l. on average. The training system is the espalier with guyot pruning system and the density of plantation of 3,000 vines/ha on average and the yield is of about 8,000 kg/ha (7,140 lbs/acres) and 2.6 kg/vine (5,80 lbs/vine). W I N E P R O D U C T I O N Classic white vinification in stainless tanks at controlled temperature. Refines for at least 1 month in bottle. T A S T I N G N O T E S Straw yellow in color with an intense bouquet of tropical fruit and white flowers. This Greco is fresh and fruity on the palate, with a lively acidity. F O O D P A I R I N G Ideal with small plates, appetizers, fresh fish and salads, as well as an aperitif. V I N E Y A R D & P R O D U C T I O N I N F O Vineyard size: 20 acres Soil composition: Calcareous and Clay-Loam Training method: Guyot Espalier Elevation: 1,155 feet Vines/acre: 1,200 Yield/acre: 3.2 tons Exposure: Southeastern Year vineyard planted: 1996-2000 Harvest time: October First vintage of this wine: 2010 Bottles produced of this wine: 50,000 W I N E M A K I N G & A G I N G Varietal composition: 100% Greco Fermentation container: Stainless steel tanks Length of alcoholic fermentation: 15 days Fermentation temperature: 59-61 °F Maceration technique: Sur-Lie Aging Type of aging container: Stainless steel tanks Length of aging before bottling: 3 months Length of bottle aging: 2 month P R O D U C E R P R O F I L E Estate owned by: Piero Mastroberardino A N A L Y T I C A L D A T A Winemaker: Massimo Di Renzo Alcohol: 12.5 % Total acreage under vine: 785 Residual sugar: 0.2 g/L Estate founded: 1878 Winery production: 2,400,000 Bottles Region: Campania Country: Italy ©2019 · Selected & Imported by Winebow Inc., New York, NY · winebow.com. -

CATALOG Who We Are

CATALOG Who We Are We are a recently established Consortium of Italian Winemakers. We are a group of friends that are sharing the same ideology of work and life, believing together in natural preservation of culture and in people’s relationships. Concerning productive terms, we do not use nothing a part grape. We principally want to develop a free, personal interpretation of our land and wine, having a very direct to the roots, concept of terroir. All together we are elaborating in Germany a new system of distri- bution and communication, directly managed by ourselves, the wine- makers, supporting with a direct participation, specific, local realities, like restaurants and wine bars. The general system, built up by the Consortium, will be characterized by lower, shared costs of management for us, combined with very com- petitive prices and higher general qualities of service for our client. INDEX CATALOG CANTINA DEL BARONE 1 I CACCIAGALLI 13 Paone Fiano di Avellino 2014 2 Phos 2013 14 Particella 928 Fiano di Avellino 2014 2 Masseria Cacciagalli 2012 14 CANTINE DELL’ANGELO 3 Il CANCELLIERE 15 Greco di Tufo 2014 4 Vendemmia 2014 16 Greco di Tufo Torre Favale 2014 4 Gioviano 2012 16 Nero Nè Taurasi 2010 17 CASÈ 5 PODERE CASACCIA 18 Calcaròt 2014 6 Casè Bianco 2015 6 Aliter 2015 19 Casè Riva del Ciliegio 2013 7 Sine Felle Rosato 2016 19 Harusame Metodo Classico 2014 7 Sine Felle Chianti Riserva 2009 20 Assolato 2010 Vin Santo (375 ml) 20 COSTADILÀ 8 PODERE PRADAROLO 21 Costadilà 450 slm 2016 9 Costadilà 280 slm 2016 9 Velius 2011 22 Vej 210 2015 22 Vej Metodo Classico 2013 23 10 FRANCO TERPIN 11 PODERE VENERI VECCHIO 24 Ribolla Gialla 2009 11 Jakot 2010 12 Rutilum 2014 25 Sialis Bianco 2008 Bianco Tempo 2014 25 Il Tempo Ritrovato 2014 26 CANTINA DEL BARONE CAMPANIA “Cantina del Barone” born on the sunny hills of Cesinali, a small farming village in the area of Avellino, where the Sarno family has been looking after their own land for over a century. -

• Wine List • by the Glass Champagne & Sparkling

• WINE LIST • BY THE GLASS CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING Elvio Tintero ‘Sori Gramella’ NV Moscato d’Asti DOCG 46 Piedmont, IT SPARKLING “Sori” means South-facing slope in Piedmontese Zonin Prosecco NV Brut 13 Veneto, IT Zonin NV Brut Prosecco 52 Veneto, IT Prosecco is style of wine as well as a recognized appellation Domaine Chandon ‘étoile’ NV Rosé 23 North Coast, CA Domaine Chandon NV Brut 65 CA Napa Valley’s branch of the famous Champagne house WHITE Enrico Serafino 2013 Brut Alta Langa DOCG 74 Cà Maiol Lugana, Trebbiano 11 Piedmont, IT 2018, Veneto, IT The Serafino winery was founded in 1878 Santa Cristina Pinot Grigio 14 Laurent Perrier ‘La Cuvee’ NV Brut Champagne 90 2017, Tuscany, IT The fresh style is from the high proportion of Chardonnay in the blend Mastroberardino Falanghina del Sannio 16 2017, Campania, IT Moët & Chandon ‘Imperial’ NV Brut Champagne 104 Cakebread Sauvignon Blanc 20 Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage 2012 Brut Champagne 180 2018, Napa Valley, CA Established in 1743 by Claude Moët Flowers Chardonnay 24 Monte Rossa ‘Coupe’ NV Ultra Brut Franciacorta DOCG 110 2016, Sonoma Coast, CA Franciacorta is Italy’s answer to Champagne Veuve Clicquot ‘Yellow Label’ NV Brut Reims, Champagne 132 RED Veuve Clicquot ‘La Grande Dame’ Brut Reims, Champagne 260 Tascante Etna Rosso, Nerello Mascalese 13 2008 This iconic estate is named for the widow who invented ‘remouage’ 2016, Sicily, IT Frederic Savart ‘L’Ouverture’ 150 Tua Rita ‘Rosso Dei Notri’ Sangiovese Blend 16 2016, Tuscany, IT NV Brut Blanc de Noirs 1er Cru Champagne Pra ‘Morandina’, -

BEER /Cid Er Red COCKT AIL S N/A FL IGH T Bu B Bl Es Whit E D Esse Rt

Almanac Beer Co. Peach Sour Nova 5.3% – Alameda, CA 10oz 8 Coronado Brewing Co. Weekend Vibes IPA 6.8% – San Diego, CA 12oz 6 Fort Point Beer Co. “Sfizo” Pilsner 4.9% - SF, CA. 12oz 6 /Cider Flying Dog Brewery Gonzo Imperial Porter 10% – Frederick, MD 12oz 9 Santa Cruz Cider Co. “Gravenstein” 6.9% - Santa Cruz, CA. 500mL 8 BEER Santa Cruz Cider Co. “Lot 18” 6.9% - Santa Cruz, CA. 500mL 8 Cabernet Franc Flight 20 2oz each 2020 Domaine de Souchiere Rosé Cabernet Franc - Loire Valley, France 14 / 45 2018 Savage Grace Blanc de Cabernet Franc - Yakima Valley, Washington 14 / 43 2019 Chaintres "Les Sables" Saumur Champigny Cabernet Franc - Loire Valley, France 15 / 46 FLIGHT 2017 Chateau de l"Eperonniere" Crémant Chenin Blanc/Cabernet Franc – Loire, France 14 / 45 NV J. Lassalle “Cachet Or” Brut Réserve Premier Cru Traditional Blend – Champagne, France 18 / 59 bubbles 2019 Cenatiempo Ischia Bianco Biancolella/Forastera/Local Grapes - Campania, Italy 14 / 43 2018 Reyneke "Vinehugger" Chenin Blanc - Stellenbosch, South Africa 12 / 39 2020 Toreta "Special" Posip - Korcula Island, Croatia 14 / 41 2017 Rhys Vineyards “Alesia” Chardonnay - Santa Cruz Mountains, California 17 / 56 White 2019 Paul Durdilly "Les Grandes Coasses" Gamay - Beaujolais, France 12 / 40 2018 Bachelet-Monnot Bourgogne Rouge Pinot Noir - Burgundy, France 17 / 55 2019 COS Terre Siciliane Frappato – Sicily, Italy 15 / 48 2018 Domaine De Fontsainte Carignan/Grenache Noir/Mourvèdre - Corbières, France 13 / 40 red 2019 Lionel Faury Collines Rhodaniennes Syrah – Rhône, France -

7Th-11Th April 2017 Vinitaly 2017 7Th-11Th April 2017 Vinitaly 2017 7Th-11Th April 2017 on the Road Kate Lucas a Word from the Team

vinitaly 7th-11th April 2017 vinitaly 2017 7th-11th April 2017 vinitaly 2017 7th-11th April 2017 on the road Kate Lucas A word from the team Earlier this month, a team of Enotria&Coe Italian-wine enthusiasts travelled to Verona, Italy, for Kate’s top picks for the 51st edition of Vinitaly. This year, more than 128,000 visitors from 142 countries travelled to Vinitaly 2017 the Italian city for the four-day festival which, over the years, has established its status as one Over the course of the world’s most important wine and spirits exhibitions. In the following pages, our travelling of the festival team spills some of their highlights from the trip. we tasted some truly amazing Ed Donnelly wines, but two Pina Bello which really stick out in my mind was the new Pecorino from Umani Ronchi and the 2016 Valpolicella from Bertani. We were incredibly lucky in that the wines from all producers were showing really well, but in particular, the line-ups from Umani Ronchi and Fontanafredda were truly outstanding. with great passion. three best wine grapes – along with Ed’s top picks for Vinitaly 2017 Nebbiolo and Sangiovese – and Alice Gatto The Fucci family owns 6.7ha of it’s developed the reputation as Fontanafredda – The best range we Aglianico vines, which range from the ‘Barolo of the South’. Aglianico tasted in terms of variety and quality. 55 to 65 years in age. The vineyards Producer highlight: Cenatiempo was shipped to northern Italy, and The Briccotondo Arneis was marvellous, are close to the volcano’s summit, at Bordeaux, to supplement the supply The south of Italy, with its of the red wine in the glass. -

Barbera (2 Clones)

Barbera Synonym: Barbera a Peduncula Rosso, Barbera a Raspo Verde, Barbera Amaro, Barbera d’Asti, Barbera Dolce, Barbera Fina, Barbera Grossa, Barbera Nera, Barbera Nostrana, Barbera Vera, Barberone, Gaietto, Lombardesca, Sciaa Commonly mistaken for: Barbera del Sannio, Barbera Sarda, Mammolo, Neretto Duro, Perricone Origin: Doubt surrounds the origins of Barbera: is it a derivation of the Italian for barbarian due to its deep red colour or is its origin in an astringent, deeply coloured medieval drink named vinum berberis? Others believe that its original name was Grisa or Grisola, a word that associates the variety with the acidity of the gooseberry (Ribes grossularia L.). Unfortunately a dearth of documentation before the eighteenth century makes it difficult to be sure where the variety and its name originates. While it is viewed as a Piemonte variety with claims that it hails from the Monferrato hills, DNA profiling has shown it shares little in common with other Piemonte varieties. It is not only a Piemonte variety but is found in most regions of Italy, making it the country’s third most-planted red variety. It has also made a home in California and Australia. Agronomic and environmental aspects: Barbera typically has large bunches and medium-sized berries that are very dark in colour. It is suited to dry climates and offers good drought resistance. It has a preference for dark soils with a good percentage of clay, with medium-low fertility. Producing high yields, growers are advised to have a strict pruning regime. Diseases, pests and disorders: Spring frost susceptibility; extremely sensitive to potassium and boron deficiency. -

Beer & Cider ...3

INDEX BEER & CIDER ........................................... 3 WINE BY THE GLASS .............................7 HALF & LARGE BOTTLES ....................11 SPARKLING & ROSÉ ..............................14 WHITE WINE ...........................................16 RED WINE .................................................22 DESSERT WINE & AMARO .................. 28 LIQUOR .....................................................34 1 BEER & CIDER 3 DRAFT 4oz / 8oz / 12oz ZERO GRAVITY [VT] ‘GREEN STATE LAGER’ | CZECH PILSNER 4.9% ABV | 3 / 5 / 7 MAINE BEER COMPANY [ME] ‘A TINY SOMETHING BEAUTIFUL’ | AMERICAN PALE ALE 5.5 % ABV | 6 / 8 / 10 GRIMM [BK] ‘CAPSLOCK’ | IPA 5.5% ABV | 6 / 8 / 10 HILL FARMSTEAD [VT] ‘HARLAN’ | DRY-HOPPED AMERICAN PALE ALE 6.2% ABV | 6 / 8 / 10 HUDSON VALLEY [NY] ‘RE-UP’ | DOUBLE IPA 8.0 % ABV | 6 / 8 / 10 SUAREZ FAMILY BREWERY [NY] ‘ROUND THE BEND’ | AMERICAN PORTER 5.3% ABV | 5 / 7 / 9 4 BOTTLES & CANS SPECIALTY BEERS We carry an assortment of hard to find cans and bottles which alternate seasonaly including our rotating OTHER HALF selection Ask your server or bartender for our current selection LIGHT German Pilsener • BURIAL ‘SHADOW CLOCK’, ASHEVILLE, NC, 16OZ • 8 Belgian Blonde Ale • MIKKELLER ‘SHAPES’, SAN DIEGO, CA, 12OZ • 6 Brett Saison • OTHER HALF X 3 STARS ‘MEEK MILLET - 12 STRAIN BRETT’, BROOKLYN, NY, 500ML • 17 Farmhouse Saison • OXBOW ‘CROSS FADE’, NEW CASTLE, ME, 16OZ • 16 Witbier • THE ALCHEMIST ‘STERK WIT’, WATERBURY, VT, 16OZ • 12 Golden Ale • AGAINST THE GRAIN ‘SHO’NUFF’, LOUISVILLE, KY, 16OZ • 7 Barrel-Aged Saison • HOLY MOUNTAIN ‘THE SEER’, SEATTLE, WA, 750ML • 28 Toasted Hay Grisette • KENT FALLS ‘LADE OL’, KENT, CT, 16OZ • 16 SOUR Gose • WESTBROOK ‘WESTBROOK GOSE’, MT. PLEASANT, SC, 12OZ • 5 Sour Ale • UPLAND ‘REVIVE’, BLOOMINGTON, IN, 500ML • 16 Barrel-Aged Sour Ale • UPLAND ‘IRIDESCENT’, BLOOMINGTON, IN, 500ML • 16 Blended Lambic • DRIE FONTEINEN ‘OUDE GEUZE’ A.K.A. -

Villa Dei Misteri: the Ancient Wine of Pompeii

Villa dei Misteri: The Ancient Wine of Pompeii Everybody knows Italy has a long winemaking historydating back to Roman times, but few are aware of the fact that the same wine the citizens of ancient Rome used to drink is still being produced today. Pompeii (in the Campania region in the south of Italy) is 2000 years old. The city was covered with lava after the volcano, Vesuvio, erupted in 79 B.C. These 18th-century ruins are now visited by more than 2 million tourists each year. What’s new today is the active wine production taking place at that archaeological site! In the 1980s, the Superintendency for the Archaeological Heritagestarted a search beneath the archaeological site to discover the original plants, trees and flowers and recover them after 2000 years had passed. During their research, they discovered grapevines. They turned to Mastroberardino, an historical local winery, known for their efforts to protect and enhance thenative varieties. Researchers asked the winery to handle this piece of the research. The study progressed through several phases and the analysis of the berries and vines remainsin laboratory along with the casts of plants, similar to the amazing casts of the bodies trappedunder the lava. Based upon where the vines were located, the winery was able to reproduce the grapevines with the same density as the original ones Thanks to the numerous books written by Romans, such as Naturalis Historia by Plinio, it was possible to learn more about ancient farming techniques of the vines. In 2001, from this fascinating recovery, "Villa dei Misteri" wine (named after one of the most impressive villas in Pompeii) was born.