Downloadrailroad-Era Resources of Southwest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Extra)ORDINARY MEN

(Extra)ORDINARY MEN: African-American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas Before 1950 Judith Kilpatrick* “The remarkable thing is not that black men attempted to regain their stolen civic rights, but that they tried over and over again, using a wide va- riety of techniques.”1 I. INTRODUCTION Arkansas has a tradition, beginning in 1865, of African- American attorneys who were active in civil rights. During the eighty years following the Emancipation Proclamation, at least sixty-nine African-American men were admitted to practice law in the state.2 They were all men of their times, frequently hold- * Associate Professor, University of Arkansas School of Law; J.S.D. 1999, LL.M. 1992, Columbia University, J.D. 1975, B.A. 1972, University of California-Berkeley. The author would like to thank the following: the historians whose work is cited here; em- ployees of The Arkansas History Commission, The Butler Center of the Little Rock Public Library, the Pine Bluff Public Library and the Helena Public Library for patience and help in locating additional resources; Patricia Cline Cohen, Professor of American History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for reviewing the draft and providing comments; and Jon Porter (UA 1999) and Mickie Tucker (UA 2001) for their excellent research assis- tance. Much appreciation for summer research grants from the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1998 and 1999. Special thanks to Elizabeth Motherwell, of the Universi- ty of Arkansas Press, for starting me in this research direction. No claim is made as to the completeness of this record. Gaps exist and the author would appreciated receiving any information that might help to fill them. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Washington and Saratoga Counties in the War of 1812 on Its Northern

D. Reid Ross 5-8-15 WASHINGTON AND SARATOGA COUNTIES IN THE WAR OF 1812 ON ITS NORTHERN FRONTIER AND THE EIGHT REIDS AND ROSSES WHO FOUGHT IT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Illustrations Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown 3 Map upstate New York locations 4 Map of Champlain Valley locations 4 Chapters 1. Initial Support 5 2. The Niagara Campaign 6 3. Action on Lake Champlain at Whitehall and Training Camps for the Green Troops 10 4. The Battle of Plattsburg 12 5. Significance of the Battle 15 6. The Fort Erie Sortie and a Summary of the Records of the Four Rosses and Four Reids 15 7. Bibliography 15 2 Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown as depicted3 in an engraving published in 1862 4 1 INITIAL SUPPORT Daniel T. Tompkins, New York’s governor since 1807, and Peter B. Porter, the U.S. Congressman, first elected in 1808 to represent western New York, were leading advocates of a war of conquest against the British over Canada. Tompkins was particularly interested in recruiting and training a state militia and opening and equipping state arsenals in preparation for such a war. Normally, militiamen were obligated only for three months of duty during the War of 1812, although if the President requested, the period could be extended to a maximum of six months. When the militia was called into service by the governor or his officers, it was paid by the state. When called by the President or an officer of the U.S. Army, it was paid by the U.S. Treasury. In 1808, the United States Congress took the first steps toward federalizing state militias by appropriating $200,000 – a hopelessly inadequate sum – to arm and train citizen soldiers needed to supplement the nation’s tiny standing army. -

Battle of Cook's Mills National Historic Site

Management Battle of Statement 2019 Cook’s Mills National Historic Site of Canada The Parks Canada Agency manages one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic areas in the world. The Agency’s mandate is to protect and present these places for the benefit and enjoyment of current and future generations. This management statement outlines Parks Canada’s management approach and objectives for Battle of Cook’s Mills National Historic Site. The Battle of Cook's Mills National Historic Site is a rolling semi-rural landscape east of the Welland Canal bordering the north bank of Lyon’s Creek in the City of Welland, Ontario. It was the site of an engagement between British and Canadian troops and American forces during the War of 1812. After his unsuccessful siege of Fort Erie, Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond withdrew north and concentrated his army along the Chippawa River. In October 1814, American forces under Major-General George Izard advanced northwards. On October 18th Izard ordered Brigadier General Bissell with a force of about 900 men to march to Cook's Mills, a British outpost, to seize provisions in the form of wheat intended for British troops. On October 19th, at Cook's Mills, a heavy skirmish took place, involving men of the Glengarry Light Infantry and the 82nd, 100th and 104th Regiments. Led by Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Myers, the British and Canadian troops succeeded in their objective of assessing the American forces so that Drummond could take appropriate action. Having accomplished their reconnaissance in force they withdrew in good order. -

Arkansas Moves Toward Secession and War

RICE UNIVERSITY WITH HESITANT RESOLVE: ARKANSAS MOVES TOWARD SECESSION AND WAR BY JAMES WOODS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS Dr.. Frank E. Vandiver Houston, Texas ABSTRACT This work surveys the history of ante-bellum Arkansas until the passage of the Ordinance of Secession on May 6, 186i. The first three chapters deal with the social, economic, and politicai development of the state prior to 1860. Arkansas experienced difficult, yet substantial .social and economic growth during the ame-belium era; its percentage of population increase outstripped five other frontier states in similar stages of development. Its growth was nevertheless hampered by the unsettling presence of the Indian territory on its western border, which helped to prolong a lawless stage. An unreliable transportation system and a ruinous banking policy also stalled Arkansas's economic progress. On the political scene a family dynasty controlled state politics from 1830 to 186u, a'situation without parallel throughout the ante-bellum South. A major part of this work concentrates upon Arkansas's politics from 1859 to 1861. In a most important siate election in 1860, the dynasty met defeat through an open revolt from within its ranks led by a shrewd and ambitious Congressman, Thomas Hindman. Hindman turned the contest into a class conflict, portraying the dynasty's leadership as "aristocrats" and "Bourbons." Because of Hindman's support, Arkansans chose its first governor not hand¬ picked by the dynasty. By this election the people handed gubernatorial power to an ineffectual political novice during a time oi great sectional crisis. -

Political Activities of African-American Members of the Arkansas Legislature, 1868-73

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 "The Africans Have Taken Arkansas": Political Activities of African-American Members of the Arkansas Legislature, 1868-73 Christopher Warren Branam University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Citation Branam, C. W. (2011). "The Africans Have Taken Arkansas": Political Activities of African-American Members of the Arkansas Legislature, 1868-73. Theses and Dissertations Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE AFRICANS HAVE TAKEN ARKANSAS”: POLITICAL ACTIVITIES OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN MEMBERS OF THE ARKANSAS LEGISLATURE, 1868-73 “THE AFRICANS HAVE TAKEN ARKANSAS”: POLITICAL ACTIVITIES OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN MEMBERS OF THE ARKANSAS LEGISLATURE, 1868-73 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Christopher Warren Branam California State University, Fresno Bachelor of Arts in Journalism, 1994 May 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT African-American lawmakers in the Arkansas General Assembly during Radical Reconstruction became politically active at a time when the legislature was addressing the most basic issues of public life, such as creating the infrastructure of public education and transportation in the state. They were actively engaged in the work of the legislature. Between 1868 and 1873, they introduced bills that eventually became laws. -

The Political Career of Stephen W

37? N &/J /V z 7 PORTRAIT OF AN AGE: THE POLITICAL CAREER OF STEPHEN W. DORSEY, 1868-1889 DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Sharon K. Lowry, M.A. Denton, Texas May, 19 80 @ Copyright by Sharon K. Lowry 1980 Lowry, Sharon K., Portrait of an Age: The Political Career of Stephen W. Dorsey, 1868-1889. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1980, 447 pp., 6 tables, 1 map, bibliography, 194 titles. The political career of Stephen Dorsey provides a focus for much of the Gilded Age. Dorsey was involved in many significant events of the period. He was a carpetbagger during Reconstruction and played a major role in the Compromise of 1877. He was a leader of the Stalwart wing of the Republican party, and he managed Garfield's 1880 presidential campaign. The Star Route Frauds was one of the greatest scandals of a scandal-ridden era, and Dorsey was a central figure in these frauds. Dorsey tried to revive his political career in New Mexico after his acquittal in the Star Route Frauds, but his reputation never recovered from the notoriety he received at the hands of the star route prosecutors. Like many of his contemporaries in Gilded Age politics, Dorsey left no personal papers which might have assisted a biographer. Sources for this study included manuscripts in the Library of Congress and the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives in Santa Fe; this study also made use of newspapers, records in the National Archives, congressional investigations of Dorsey printed in the reports and documents of the House and Senate, and the transcripts of the star route trials. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Crittenden County and the Demise of African American Political Participation Krista Michelle Jones University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2012 "It Was Awful, But It Was Politics": Crittenden County and the Demise of African American Political Participation Krista Michelle Jones University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Politics Commons, Other History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Krista Michelle, ""It Was Awful, But It Was Politics": Crittenden County and the Demise of African American Political Participation" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 466. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/466 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ―IT WAS AWFUL, BUT IT WAS POLITICS‖: CRITTENDEN COUNTY AND THE DEMISE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTICIPATION ―IT WAS AWFUL, BUT IT WAS POLITICS‖: CRITTENDEN COUNTY AND THE DEMISE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTICIPATION A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Krista Michelle Jones University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History, 2005 August 2012 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Despite the vast scholarship that exists discussing why Democrats sought restrictive suffrage laws, little attention has been given by historians to examine how concern over local government drove disfranchisement measures. This study examines how the authors of disfranchisement laws were influenced by what was happening in Crittenden County where African Americans, because of their numerical majority, wielded enough political power to determine election outcomes. -

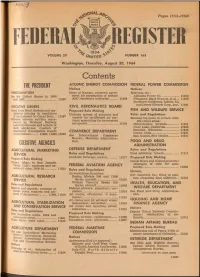

Federal^ Register

Pages 11881-11950 FEDERAL^ REGISTER 1 934 ¿ f r VOLUME 29 ^A /ITEO ^ NUMBER 163 Washington, Thursday, August 20, 1964 Contents THE PRESIDENT ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION FEDERAL POWER COMMISSION Notices Notices PROCLAMATION State of Kansas; proposed agree Hearings, etc.: See the United States in 1964 ment for assumption of certain Alabama Power Co _______ 11936 and 1965____________________11883 AEC regulatory authority_____ 11929 Pleasants, Mary Francis, et al 11936 Southern California Edison Co. and Desert Electric Corp., Inc. 11941 EXECUTIVE ORDERS CIVIL AERONAUTICS BOARD Canal Zone Merit System and reg Proposed Rule Making FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE ulations relating to conditions Uniform system of accounts and Rules and Regulations of employment in Canal Zone_11897 reports for certificated air car Disputes between carriers repre Hunting big game in certain wild- . riers; accounting for investment life refuge areas: sented by National Railway tax credits ________________11926 Labor Conference and certain of Chincoteague, Virginia-------------11921 their employees; creation of Clear Lake, California_________ 11920 emergency investigative boards COMMERCE DEPARTMENT Necedah, Wisconsin___________ 11920 (3 documents)___ 11885,11889,11893 Ouray, Utah__________________ 11921 See International Commerce San Andres, New Mexico_______11921 Bureau; Maritime Administra tion. FOOD AND DRUG EXECUTIVE AGENCIES ADMINISTRATION AGRICULTURAL MARKETING DEFENSE DEPARTMENT Rules and Regulations SERVICE Rules and Regulations Food additives; tylosin-------------- -

Railroad Era Resources of Southwest Arkansas, 1870-1945

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB Wo. 7 024-00/8 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior 'A'i*~~ RECEIVED 2280 National Park Service •> '..- National Register of Historic Places M&Y - 6 B96 Multiple Property Documentation Form NA1.REGISTER OF HISTORIC PUiICES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ________________ Railroad Era Resources Of Southwest Arkansas, 1870-1945 B. Associated Historic Contexts Railroad Era Resources Of Southwest Arkansas (Lafayette, Little River, Miller and Sevier Counties). 1870-1945_______________________ C. Geographical Data Legal Boundaries of Lafayette, Little River, Miller and Sevier Counties, Arkansas I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date Arkansas Historic Preservation Program State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for eva^ting related properties jor listing in the National Register. -

^A/ITEO NUMBER 225 Washington, Tuesday, November 20, 195J

> ’ « ITTCn»\ WÆ VOLUME 16 ^A/ITEO NUMBER 225 Washington, Tuesday, November 20, 195J TITLE 3— THE PRESIDENT the laws of the United States of America, and (2) works of citizens of Finland sub CONTENTS PROCLAMATION 2953 ject to renewal of copyright under the THE PRESIDENT C o p y r i g h t E x t e n s i o n : F in l a n d laws of the United States of America on or after September 3, 1939, there has Proclamation Pa€e BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES existed during several years of the time Finland: copyright extension.-.. 11707 OF AMERICA since September 3, 1939, such disruption A PROCLAMATION or suspension of facilities essential to Executive Order compliance with the conditions and for Creation of emergency board to WHEREAS the President Is author malities prescribed with respect to such ized, in accordance with the conditions investigate disputes between works by the copyright laws of the United Akron & Barberton Belt Railroad prescribed in section 9 of title 17 of the* States of America as to bring such works United States Code, which includes the Co. and other carriers and cer within the terms of the aforesaid title tain workers ._______________11709 provisions of the act of Congress ap 17, and that, accordingly, the time within proved March 4, 1909, 35 Stat. 1075, as which compliance with such conditions EXECUTIVE AGENCIES amended by the act of September 25, and formalities may take place is hereby 1941, 55 Stat. 732, to grant an extension extended with respect to such works for Agriculture Department of time for fulfillment of the conditions one year after the date of this proclama and formalities prescribed by the copy tion.