The Role and Impact of Institutional Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

Nationalism in Japan's Contemporary Foreign Policy

The London School of Economics and Political Science Nationalism in Japan’s Contemporary Foreign Policy: A Consideration of the Cases of China, North Korea, and India Maiko Kuroki A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, February 2013 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of <88,7630> words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Josh Collins and Greg Demmons. 2 of 3 Abstract Under the Koizumi and Abe administrations, the deterioration of the Japan-China relationship and growing tension between Japan and North Korea were often interpreted as being caused by the rise of nationalism. This thesis aims to explore this question by looking at Japan’s foreign policy in the region and uncovering how political actors manipulated the concept of nationalism in foreign policy discourse. -

Sexism in the City “We're Simply Buying Too Much”

SEPTEMBER 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Five style-defining brands that are reinventing tradition SEXISM IN THE CITY Will men and women ever be equal in Japan’s workforce? “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Change the way you shop PLUS: The Plight of the Phantom Pig, Healthy Ice Cream, The Beauties of Akita, Q&A with Paralympics Athlete Saki Takakuwa 36 20 24 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 radar in-depth guide THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS CULTURE ROUNDUP 8 AREA GUIDE: SENDAGAYA 19 SEXISM IN THE CITY 41 THE ART WORLD Where to eat, drink, shop, relax, and climb Will men and women ever be equal This month’s must-see exhibitions, including a miniature Mt. Fuji in Japan’s workforce? a “Dialogue with Trees,” and “a riotous party” at the Hara Museum. 10 STYLE 24 “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Bridge the gap between summer and fall Rika Sueyoshi explains why it’s essential 43 BOOKS with transitional pieces including one very that we start to change the way we shop See Tokyo through the eyes – and beautiful on-trend wrap skirt illustrations – of a teenager 26 THE PLIGHT OF THE PHANTOM PIG 12 BEAUTY Meet the couple fighting to save Okinawa’s 44 AGENDA We round up the season’s latest nail colors, rare and precious Agu breed Take in some theatrical Japanese dance, eat all featuring a little shimmer for a touch of the hottest food, and enter an “Edo-quarium” glittery glamor 28 GREAT LEAPS We chat with long jumper Saki Takakuwa 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES 14 TRENDS as she prepares for the 2016 Paralympics Hanging out with Cyndi Lauper, Usain Bolt, If you can’t live without ice cream but you’re and other luminaries trying to eat healthier, then you’ll love these 30 COVER FEATURE: YUKATA & KIMONO vegan and fruity options. -

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents A Mini-Guide by John Kremer Copyright © 2011 by John Kremer All rights reserved. Open Horizons P. O. Box 2887 Taos NM 87571 575-751-3398 Fax: 575-751-3100 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bookmarket.com Introduction Below are the names and contact information for more than 1,450+ literary agents who sell rights for books. For additional lists, see the end of this report. The agents highlighted with a bigger indent are known to work with self-publishers or publishers in helping them to sell subsidiary, film, foreign, and reprint rights for books. All 325+ foreign literary agents (highlighted in bold green) listed here are known to work with one or more independent publishers or authors in selling foreign rights. Some of the major literary agencies are highlighted in bold red. To locate the 260 agents that deal with first-time novelists, look for the agents highlighted with bigger type. You can also locate them by searching for: “first novel” by using the search function in your web browser or word processing program. Unknown author Jennifer Weiner was turned down by 23 agents before finding one who thought a novel about a plus-size heroine would sell. Her book, Good in Bed, became a bestseller. The lesson? Don't take 23 agents word for it. Find the 24th that believes in you and your book. When querying agents, be selective. Don't send to everyone. Send to those that really look like they might be interested in what you have to offer. -

The Technological Imaginary of Imperial Japan, 1931-1945

THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Stephen Moore August 2006 © 2006 Aaron Stephen Moore THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 Aaron Stephen Moore, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 “Technology” has often served as a signifier of development, progress, and innovation in the narrative of Japan’s transformation into an economic superpower. Few histories, however, treat technology as a system of power and mobilization. This dissertation examines an important shift in the discourse of technology in wartime Japan (1931-1945), a period usually viewed as anti-modern and anachronistic. I analyze how technology meant more than advanced machinery and infrastructure but included a subjective, ethical, and visionary element as well. For many elites, technology embodied certain ways of creative thinking, acting or being, as well as values of rationality, cooperation, and efficiency or visions of a society without ethnic or class conflict. By examining the thought and activities of the bureaucrat, Môri Hideoto, and the critic, Aikawa Haruki, I demonstrate that technology signified a wider system of social, cultural, and political mechanisms that incorporated the practical-political energies of the people for the construction of a “New Order in East Asia.” Therefore, my dissertation is more broadly about how power operated ideologically under Japanese fascism in ways other than outright violence and repression that resonate with post-war “democratic” Japan and many modern capitalist societies as well. This more subjective, immaterial sense of technology revealed a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of technology. -

Jewish Fiction 2016-2017 Title Author Publisher Year 4 3 2 1 Paul Auster

Jewish Fiction 2016-2017 Title Author Publisher Year 4 3 2 1 Paul Auster Macmillan/Henry Holt 2017 About the Night Anat Talshir Amazon Crossing 2016 Address in Amsterdam, An Mary Dingee Fillmore She Writes Press 2016 After Anatevka Alexandra Silber WW Norton/Pegasus 2017 Afterlife of Stars, The Joseph Kertes Little Brown 2017 Albina and the Dog-Men Alejandro Jodorowsky Restless Books 2016 All the Rivers Dorit Rabinyan Random House 2017 Among the Living Jonathan Rabb Other Press 2016 Among the Survivors Ann Leventhal She Writes Press 8/22/2017 And After the Fire Lauren Belfer Harper 2016 And So Is the Bus: Jerusalem Stories Yossel Birstein Dryad Press 2016 As Close to Us As Breathing Elizabeth Poliner Lee Boudreaux Books 2016 Awkward Age, The Francesca Segal Penguin Random House/Riverhead Books 2017 Beautiful Possible, The Amy Gottlieb Harper Perennial 2016 Beauty Queen of Jerusalem, The Sarit Yishai-Levi Random House 2016 Bed Moved, The Rebecca Schiff Knopf 2016 Bed-Stuy Is Burning Brian Platzer Atria 7/11/2017 Béla’s Letters Jeff Ingber Self-Published 2016 Beneath a Scarlet Sky Mark T. Sullivan Lake Union 2017 Best Place on Earth, The: Stories Ayelet Tsabari Random House 2016 Betrand Place Michelle Brafman Prospect Park Books 2016 Between Life and Death Yoram Kaniuk Restless Books 2016 Black Widow Daniel Silva HarperCollins 2016 Bone Box Faye Kellerman HarperCollins/William Morrow 2017 Book of Blam, The Aleksandar Tisma Random House 2016 Book of Esther, The Emily Barton Random House 2016 Boy in Winter, A Rachel Seiffert Knopf Doubleday/Pantheon -

Indiebestsellers

Indie Bestsellers Week of 02.23.12 HardcoverFICTION NONFICTION 1. Death Comes to Pemberley 1. Behind the Beautiful Forevers P.D. James, Knopf, $25.95 Katherine Boo, Random House, $27 2. The Sense of an Ending 2. Quiet Julian Barnes, Knopf, $23.95 Susan Cain, Crown, $26 3. The Art of Fielding 3. Steve Jobs Chad Harbach, Little Brown, $25.99 Walter Isaacson, S&S, $35 4. Kill Shot 4. Unbroken Vince Flynn, Atria, $27.99 Laura Hillenbrand, Random House, $27 5. The Paris Wife Paula McLain, Ballantine, $25 5. All There Is Dave Isay, Penguin Press, $24.95 ★ 6. What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank: Stories 6. Bringing Up Bébé Nathan Englander, Knopf, $24.95 Pamela Druckerman, Penguin Press, $25.95 7. The Marriage Plot 7. In the Garden of Beasts Jeffrey Eugenides, FSG, $28 Erik Larson, Crown, $26 ★ 8. The Wolf Gift 8. The End of Illness Anne Rice, Knopf, $25.95 David B. Agus, M.D., Free Press 9. State of Wonder 9. American Sniper Ann Patchett, Harper, $26.99 Chris Kyle, et al., Morrow, $26.99 10. 11/22/63 Stephen King, Scribner, $35 10. Killing Lincoln Bill O’Reilly, Martin Dugard, Holt, $28 11. Raylan Elmore Leonard, Morrow, $26.99 11. The Science of Yoga William J. Broad, S&S, $26 12. The Orphan Master’s Son Adam Johnson, Random House, $26 12. Thinking, Fast and Slow Daniel Kahneman, FSG, $30 13. Believing the Lie Elizabeth George, Dutton, $28.95 13. Once Upon a Secret 14. The Night Circus Mimi Alford, Random House, $25 Erin Morgenstern, Doubleday, $26.95 14. -

Bottom-Line Pressures in Publishing: a Panel Discussion

BOTTOM-LINE PRESSURES IN PUBLISHING: A PANEL DISCUSSION http://www.najp.org This is an edited and abbreviated transcript of a National Arts Journalism Program panel on the effect of bottom-line pressures on the publishing industry held at Columbia University on April 17, 1998. Panelists: Susan Bergholz, literary agent based in New York City. Formerly a bookseller, Ms. Bergholz has also worked as a buyer for Endicott. Lee Buttala, Associate Editor at Alfred A. Knopf, where he has worked since 1995. Previous to that, he was an editor at Interview and Metropolitan Home magazines. Jeff Seroy, Vice President and Publicity Director, Farrar, Straus & Giroux. A graduate of Columbia University, Mr. Seroy was awarded a Kellett Fellowship for continuing studies at Cambridge University for the 1976-77 academic year, after which he entered the publishing industry. Elisabeth Sifton, Senior Vice President, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, and Publisher, Hill & Wang. Ms. Sifton has held editorial and executive positions at The Viking Press, Viking Penguin, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and Elisabeth Sifton Books, which won the Carey-Thomas Award for Creative Publishing in 1986. William B. Strachan, President and Director, Columbia University Press. Formerly editor in chief at Henry Holt, Mr. Strachan has worked at a number of other trade publishers throughout his career including Viking Press and Anchor Press. Moderators: Ruth Lopez, 1997-98 NAJP Fellow, Book Review editor at The Santa Fe New Mexican. Carlin Romano, 1997-98 NAJP Senior Fellow, literary critic, The Philadelphia -

Masterarbeit

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit „’I live to love my friends, live to love the soil, live for the people’: The (anti-)utopia of Kirino Natsuo’s Poritikon“ Verfasst von Adam Gregus, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 843 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Japanologie Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ina Hein, M.A. Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Ina Hein, whose guidance has been invaluable for me throughout the writing of this thesis. It is also thanks to Prof. Hein that I discovered the work of Kirino Natsuo, so it is fair to say that her presence has been instrumental in the choice of my topic. I am also indebted to Prof. Hein for her generosity and the time she had spent on her correctures, remarks, as well as discussions about the thesis. I do not take any of this for granted, and I am convinced I could not have wished for a better supervisor. I am also most grateful to my parents, without whose support I would not have been able to concentrate on the thesis, as well as all of my studies as intensely as I could. Concerning the thesis, my thanks also go out to my friend Lucia, who has supplied me with sources for the thesis, not least the novel Poritikon itself, as well as other publications by Kirino Natsuo. Thanks to her, I have been able to get hold of these materials in an affordable and comfortable manner even outside of Japan. -

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

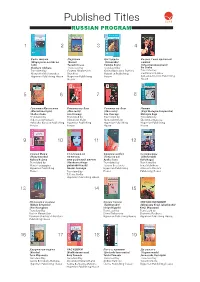

Published Titles RUSSIAN PROGRAM

Published Titles RUSSIAN PROGRAM 1 2 3 4 Сопь жизни Лоулань Цитадель Косые тени далекой (Waga jinsei no toki no (Roran) (Onnazaka) земли toki) Yasushi Inoue Fumiko Enchi (Shaei harukana kuni) Shintaro Ishihara Translated by Translated by Go Osaka Translated by Evgeny Nikolaevich Galina Borisovna Dutkina Translated by Alexander Mesheryakov Kruchina Hyperion Publishing Liudmila Ermakova Hyperion Publishing House Hyperion Publishing House Azbooka-Klassica Publishing House House 5 6 7 8 Госпожа Мусасино Ронины из Ако Ронины из Ако Лимон (Musashino fujin) (Ako roshi) (Ako roshi) (Kajii Motojiro tanpenshu) Shohei Ooka Jiro Osaragi Jiro Osaragi Motojiro Kajii Translated by Translated by Translated by Translated by Aida Souleymenova Alexander Dolin Alexander Dolin Ekaterina Ryabova Azbooka-Klassica Publishing Hyperion Publishing Hyperion Publishing Hyperion Publishing House House House House 9 10 11 12 Семья Мива Стоиеновая Синева небес Соперницы (Hoyo kazoku) певичка, (Tenjo no ao) (Udekurabe) Nobuo Kojima или райский ангел Ayako Sono Kafu Nagai Translated by (Hyakuen shinga Translated by Translated by Maria Toropygina gokuraku tenshi) Tatiana Breslavets Irina Melnikova Hyperion Publishing Naomi Suenaga Hyperion Publishing Azbooka-Klassica House Translated by House Publishing House Tatiana Redko Hyperion Publishing House 13 14 15 Пленники войны Сверстники ЗВЕЗДА КОЗОДОЯ (Nihon horyoshi) (Takekurabe) (Miyazawa Kenji sakuhinshu) Shin Hasegawa Ichiyo Higuchi Kenji Miyazawa Translated by Translated by Translated by Karine Marandjian Elena Diakonova -

International Fiction Book Club Was Held by Zoom on Monday 21 June 2021 at 6.30Pm

International Fiction Book Club Yu Miri – Tokyo Ueno Station Monday 21 June 2021, 6.30pm by Zoom The fourteenth meeting of the Litfest International Fiction Book Club was held by Zoom on Monday 21 June 2021 at 6.30pm. We discussed Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri, translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles, and published in paperback and as an eBook by Tilted Axis Press. About the Book ‘Kazu's painful past and ghostly present are the subject of … the latest book by Korean-Japanese author Yu Miri ... It's a relatively slim novel that packs an enormous emotional punch, thanks to Yu's gorgeous, haunting writing and Morgan Giles' wonderful translation’ Michael Schaub, npr.org ‘How Kazu comes to be homeless, and then to haunt the park, is what keeps us reading, trying to understand the tragedy of this ghostly everyman. Deftly translated by Morgan Giles’ Lauren Elkin, Guardian We chose this book for its restrained but powerful portrayal of a homeless man who had worked on building sites for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and now, as preparations for the 2020 games are being made, finds himself one of many living in the park next to the station. If you haven’t read Tokyo Ueno Station yet, we hope you will. Time differences between the UK and Australia prevented Tony Malone, whose blog Tony’s reading list is essential for anyone interested in what’s new in fiction in translation, and who incidentally is the instigator of the Shadow Booker International Prize, from joining us on the day but he kindly answered our questions by email.