Masterarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hayashi Fumiko: the Writer and Her Works

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship East Asian Studies 1994 Hayashi Fumiko: The Writer and Her Works Susanna Fessler PhD University at Albany, State University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/eas_fac_scholar Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fessler, Susanna PhD, "Hayashi Fumiko: The Writer and Her Works" (1994). East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship. 13. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/eas_fac_scholar/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the East Asian Studies at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Asian Studies Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualify of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bieedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan

100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan The Nippon Foundation Copyright © 2008 All rights reserved The Nippon Foundation The Nippon Zaidan Building 1-2-2 Akasaka, Minato-ku Tokyo 107-8404, Japan Telephone +81-3-6229-5111 / Fax +81-3-6229-5110 Cover design and layout: Eiko Nishida (cooltiger ltd.) February 2010 Printed in Japan 100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan Foreword 7 On the Selection Process 9 Program Committee 10 Politics / International Relations The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa / Yukichi Fukuzawa 12 Broadcasting Politics in Japan: NHK and Television News / Ellis S. Krauss 13 Constructing Civil Society in Japan: Voices of Environmental Movements / 14 Koichi Hasegawa Cultural Norms and National Security: Police and Military in Postwar Japan / 15 Peter J. Katzenstein A Discourse By Three Drunkards on Government / Nakae Chomin 16 Governing Japan: Divided Politics in a Major Economy / J.A.A. Stockwin 17 The Iwakura Mission in America and Europe: A New Assessment / 18 Ian Nish (ed.) Japan Remodeled: How Government and Industry are Reforming 19 Japanese Capitalism / Steven K. Vogel Japan Rising: The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose / 20 Kenneth B. Pyle Japanese Foreign Policy at the Crossroads / Yutaka Kawashima 21 Japan’s Love-Hate Relationship with the West / Sukehiro Hirakawa 22 Japan’s Quest for a Permanent Security Council Seat / Reinhard Drifte 23 The Logic of Japanese Politics / Gerald L. Curtis 24 Machiavelli’s Children: Leaders and Their Legacies in Italy and Japan / 25 Richard J. Samuels Media and Politics in Japan / Susan J. Pharr & Ellis S. Krauss (eds.) 26 Network Power: Japan and Asia / Peter Katzenstein & Takashi Shiraishi (eds.) 27 Regime Shift: Comparative Dynamics of the Japanese Political Economy / 28 T. -

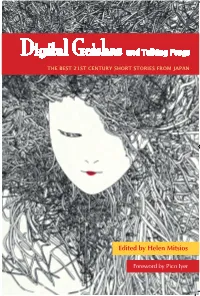

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

March 10—April 27, 2006 in THIS ISSUE WELCOME to Contents the SILVER! in Less Than Three Years, AFI Silver Theatre 2

AMERICAN FILM INSITUTE GUIDE TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS March 10—April 27, 2006 IN THIS ISSUE WELCOME TO Contents THE SILVER! In less than three years, AFI Silver Theatre 2. LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR has established itself as one of Washington’s premier cultural destinations, with BILLY WILDER AT 100 3. exceptional movies, premieres 3. SPECIAL EVENT: SOME LIKE IT HOT, WITH and star-studded events. To AFI FOUNDING DIRECTOR GEORGE STEVENS, JR. spread the word, we’re delight- ed to offer our AFI PREVIEW film 6. JAPANESE MASTER MIKIO NARUSE: “A CALM SURFACE programming guide to AFI Silver AND A RAGING CURRENT” Members and more than 100,000 households in the area through The 9. CINEMA TROPICAL: 25 WATTS, DIAS DE SANTIAGO Gazette. To those of you new to AFI Silver, welcome. And to our more AND EL CARRO than 5,000 loyal members, thank you for your continued support. With digital video projection and Lucasfilm THX certification in all 10. THE WORLD OF TERRENCE MALICK three of its gorgeous theaters, AFI Silver also offers the most advanced and most comfortable movie-going experience available anywhere. If SAVE THE DATE! SILVERDOCS: “THE PRE-EMINENT 11. you haven’t visited yet, there’s a treat waiting for you. From the earliest US DOCUMENTARY FEST” silent movies to 70mm epics to the latest digital technologies, AFI Silver 12. MEMBERSHIP NEWS connects you to the best the art form has to offer. Just leaf through these pages and see what is in store for you. This 13. SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS: LIMITED RUNS! past year, in addition to such first-run sensations as CRASH, HOTEL BLACK ORPHEUS, THE RIVER AND MOUCHETTE RWANDA, MARCH OF THE PENGUINS and GOOD NIGHT, AND 14. -

International Fiction Book Club Was Held by Zoom on Monday 21 June 2021 at 6.30Pm

International Fiction Book Club Yu Miri – Tokyo Ueno Station Monday 21 June 2021, 6.30pm by Zoom The fourteenth meeting of the Litfest International Fiction Book Club was held by Zoom on Monday 21 June 2021 at 6.30pm. We discussed Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri, translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles, and published in paperback and as an eBook by Tilted Axis Press. About the Book ‘Kazu's painful past and ghostly present are the subject of … the latest book by Korean-Japanese author Yu Miri ... It's a relatively slim novel that packs an enormous emotional punch, thanks to Yu's gorgeous, haunting writing and Morgan Giles' wonderful translation’ Michael Schaub, npr.org ‘How Kazu comes to be homeless, and then to haunt the park, is what keeps us reading, trying to understand the tragedy of this ghostly everyman. Deftly translated by Morgan Giles’ Lauren Elkin, Guardian We chose this book for its restrained but powerful portrayal of a homeless man who had worked on building sites for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and now, as preparations for the 2020 games are being made, finds himself one of many living in the park next to the station. If you haven’t read Tokyo Ueno Station yet, we hope you will. Time differences between the UK and Australia prevented Tony Malone, whose blog Tony’s reading list is essential for anyone interested in what’s new in fiction in translation, and who incidentally is the instigator of the Shadow Booker International Prize, from joining us on the day but he kindly answered our questions by email. -

Center for Japanese Studies 50Th Anniversary Hybrid Japan

Center for Japanese Studies 50th Anniversary Hybrid Japan Haruki Murakami: A Conversation October 10 – October 12, 2008 Japanese Literature on the Global Stage: The Murakami Symposium All 50th Anniversary Events Video Archive On Saturday, October 11th, 2008, the Center for Japanese Studies presented a special reading and lecture by world- renowned Japanese novelist, Haruki Murakami, at UC Berkeley's Zellerbach Hall in front of a sold-out crowd. Murakami offered a reading, in both Japanese and English, of a short story called "The Rise and Fall of Sharpie Cakes." He shared with the audience his story of how he went from being the manager of a Tokyo jazz club to becoming a writer. This was followed by an on-stage conversation with Roland Kelts (author of Japanamerica), where they discussed everything from Murakami's works, his day-to-day routine, writing process, and hobbies. An audience Q&A followed the interview. On the previous afternoon, Friday, October 10th, Murakami was honored with the Inaugural Berkeley Japan Prize, a lifetime achievement award from the Center for Japanese Studies to an individual who has made significant contributions in furthering the understanding of Japan on the global stage. The award ceremony was held at the Morrison Reading Room in the Doe Library. Earlier in the afternoon, Murakami made a guest appearance at two Japanese literature classes at UC Berkeley where students were able to ask him about his novels that they were reading in their classes. On Sunday, October 12th, the Center for Japanese Studies presented a symposium featuring a distinguished panel of speakers to discuss Haruki Murakami's writings and the impact it has had in bringing Japanese literature to the global stage. -

The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Literature Kathryn Hemmann University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hemmann, Kathryn, "The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Literature" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 762. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/762 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/762 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Literature Abstract The female gaze can be used by writers and readers to look at narratives from a perspective that sees women as subjects instead of objects. Applying a female gaze to discourses that have traditionally been male-dominated opens new avenues of interpretation that are empowering from a feminist perspective. In this dissertation, I use the murder mystery novels of the bestselling female author Kirino Natsuo and the graphic novels of a prolific four-woman artistic collective called CLAMP to demonstrate how writers are capable of applying a female gaze to the themes of their work and how readers can and have read their work from the perspectives allowed by a female gaze. Kirino Natsuo presents a female perspective on such issues as prostitution, marriage, and equal employment laws in her novels, which are often based on sensationalist news stories. Meanwhile, CLAMP challenges the discourses surrounding the production and consumption of fictional women, especially the young female characters, or shojo, that have become iconic in Japanese popular culture. -

Ojos Marrones: Traducción Comentada De Los Tres Primeros Capítulos De La Novela Chairo No Me, De Hayashi Fumiko

FACULTAT DE TRADUCCIÓ I INTERPRETACIÓ GRAU DE TRADUCCIÓ I INTERPRETACIÓ TREBALL DE FI DE GRAU Curs 2018-2019 Ojos marrones: traducción comentada de los tres primeros capítulos de la novela Chairo no me, de Hayashi Fumiko Catalina Fernández Utiel NIU 1311468 TUTOR Albert Nolla Cabellos Barcelona, juny de 2019 Datos del TFG Título: Ojos marrones: traducción comentada de los tres primeros capítulos de la novela Chairo no me, de Hayashi Fumiko Autora: Catalina Fernández Utiel Tutor: Albert Nolla Cabellos Centro: Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona Estudios: Grado de Traducción e Interpretación Curso académico: 2018 - 2019 Palabras clave Literatura japonesa moderna, Hayashi Fumiko, Chairo no me (Ojos marrones), traducción, traducción comentada. Resumen del TFG En este trabajo nos centraremos esencialmente en la novela Ojos marrones (茶色の眼, Chairo no me), una obra inédita hasta el momento en castellano, de la que comentaremos brevemente algunos aspectos temáticos y literarios, así como el contexto en el que se dio su escritura, y presentaremos también una propuesta de traducción de algunos capítulos junto a la que analizaremos la metodología seguida y los problemas encontrados en el proceso. Su escritora, Hayashi Fumiko, fue una novelista y reportera de guerra japonesa de mediados del siglo XX que obtuvo una gran popularidad en la posguerra y destaca en general por la temática feminista de sus obras, entre las que también cabe resaltar especialmente Diario de una vagabunda (放浪記, Horoki), un libro autobiográfico publicado por entregas en la década de 1930 que la consagró como escritora, y que en España fue traducido por la editorial Satori en el 2014. -

A Critical Analysis of Natsuo Kirino's Grotesque University of Oslo

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF NATSUO KIRINO’S GROTESQUE ØYVOR NYBORG MASTER’S THESIS IN EAST ASIAN LINGUISTICS (EAL4090) (60 credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages (IKOS) Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2012 © Øyvor Nyborg 2012 A Critical Analysis of Natsuo Kirino’s Grotesque Øyvor Nyborg http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo Abstract This study is based on the Japanese novel Grotesque (Gurotesuku) by Natsuo Kirino. I use Judith Butler’s theories of gender performativity and interpellation as a framework to analyze the four main female characters, the unnamed narrator ‘Watashi’, her sister Yuriko, and her classmates Kazue and Mitsuru, and how they are formed and re-formed by the power structures surrounding them. How does the environment we grow up in form whom we become, or to ask in a different way; how much do our surroundings have to say in the constitution of us as discursive subjects? Using Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and field, and different forms of capital, I put Butler’s theories in a social context, and explain how the main characters in Grotesque can be said to be influenced by the social rules and unwritten norms surrounding them. I also look into some aspects of translation theory, and how the way Grotesque has been translated into English can be said to affect the way it can be read and interpreted. Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

下載小冊子download Booklet

主辦 Presented by ──── 資助 Supported by ──── 序言 Foreword 1 去年十一月,影意志在澳門舉辦了首屆為期兩週的電影節,以票房來說,實在談不上成功, 在宣傳和選片等細節上,有很多可以改善的地方。當今年籌備新一屆電影節期間,偶然在一 個聚會中遇上一名澳門年輕導演,他告訴我他很期待我們新一屆的電影節,因為去年他在節 中看了專題放映「獨立經典:約翰·卡薩維蒂 John Cassavetes」系列中的《受影響的女人》 A Woman Under the Influence,令他留下深刻印像,這次經驗不單讓他愛上了舊電影,更 讓他發現電影其實有很多可能性,甚至影響了他的創作思維。這年輕人的一番話無疑是對我們 團隊一個很大的鼓勵。 數碼年代,拍電影看似很容易,但放映的門檻卻好像愈來愈高,我們作為推廣獨立電影的團 體,著實不希望跟從主流的一套模式。今年適逢文化局「戀愛·電影館」正式諬用,我們可以 更自主地去策劃電影節及未來一年的放映,一方面我們會繼續向澳門觀眾介紹一些經典電影, 因為對電影來說,是否經得起時間考驗,比票房或獎項更能證明作品的價値。期待楊德昌和成 瀨巳喜男的專題可再次衝擊澳門的年輕朋友;另一方面我們也會放映港澳兩地獨立電影人的近 作,令三地導演有更好的交流機會。 影意志一直強調獨立自主,一向有自己的一套理念去製作和推廣電影,但也不是只盲目反對 工業模式,而是相信工業背後是需要有文化、知識作為基礎的。 這條路很漫長,創作人和觀眾都需要參與其中,希望我們可以共同建構好這個電影平台。 崔允信 影意志(澳門)創作總監 澳門電影節2015策展人 Last year during November, Ying E Chi launched the first Macau Film Festival for two weeks. We can’t say it’s a huge success in terms of box office. There are a lot to be improved regarding promotion and film selection among other details. When we were preparing for the film festival this year, we encountered this young director from Macau. He expressed his eager anticipation for the festival because last year he was impressed by Woman Under the Influence played during the featured series “Indie classics-John Cassavetes”. That experience not only enchanted him with old movies, but also enabled him to see the possibilities in films and even influenced his creative mind. This is indeed one big encouragement to the organizing team. It looks a lot easier to make movies in a digital era, yet the barrier of screening films seems ever higher. As an organization that promotes independent movies, we are reluctant to adopt the mainstream mode of practice. Since The Cultural Affairs Bureau launched its Cinematheque. Passion, we are now more autonomous in planning for the festival and arranging screenings throughout the year. -

Hard-Boiled Homemakers: the Individual and the Dystopian Urban in the Japanese Anti‑Detective Novel

Hard-boiled homemakers: The individual and the dystopian urban in the Japanese anti-detective novel DAVID TAGLIABUE Abstract This paper discusses the ways in which Japanese authors have engaged with the tropes of hard-boiled detective fiction in order to examine post- capitalist Japanese society. With reference to the extant framework on the relationship between hard-boiled fiction and the urban space, discussion will focus on two Japanese novels: Natsuo Kirino’s Out (アウト, 1997), and Haruki Murakami’s Dance Dance Dance (ダンス・ダンス・ダンス, 1983). Both texts depict individuals who have been displaced to the spatial and socioeconomic ‘margins’ of a dystopian urban space, and who, through narratives of crime and detection, attempt to escape its mundane oppression. However, both texts also challenge the hard-boiled genre through an integration of detective fiction archetypes with post-modern textual elements. Accordingly, they are emblematic of the emergent ‘anti- detective’ novel, which denies the hermetic and cathartic aspects of the traditional crime novel to discuss irresolvable issues of modern identity. Nonetheless, whilst Dance uses surreal ‘dream spaces’ as a source of relief for its protagonist, Out instead ultimately critiques its own escapist fantasy through stark violence. Regardless, both texts argue personal autonomy can only be achieved by the rejection of the urban space itself for an arguably unattainable imaginary. 63 The ANU Undergraduate Research Journal Introduction In the aftermath of World War II, the detective novel has been typically concerned at some level with what hard-boiled author Raymond Chandler termed ‘the world you live in’.1 More specifically, crime writers in the post-war period have increasingly engaged with the relationship between emergent urban capitalist societies and the individuals residing within them as a source of narrative conflict and mystery. -

The Role and Impact of Institutional Programs

THE TRANSLATING, REWRITING, AND REPRODUCING OF HARUKI MURAKAMI FOR THE ANGLOPHONE MARKET David James karashima Dipòsit Legal: T. 1497-2013 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora.