Ethiopian Journal Health Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Media, Conflict, and the State in Africa

media, conflict and the state in africa Countries emerging from violent conflict face difficult challenges about what the role of media should be in political transitions, particularly when attempting to build a new state and balance a difficult legacy. Media, Conflict and the State in Africa discusses how ideas, institutions and interests have shaped media systems in some of Africa’s most com- plex state- and nation-building projects. This timely book comes at a turbulent moment in global politics as waves of populist protests gain traction and concerns continue to grow about fake news, social media echo chambers and the increasing role of both traditional and new media in waging wars or influencing elections. Focusing on comparative cases from a historical perspective and the choices and ideas that informed the approaches of some of Africa’s leaders, including guerrilla commanders Yoweri Museveni of Uganda and Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia, Nicole Stremlau offers a unique political insight into the development of contemporary media systems in Africa. nicole stremlau is head of the Programme in Comparative Media Law and Policy, Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, at the University of Oxford and research professor in humanities at the University of Johannesburg. She has conducted extensive research in Eastern Africa and previously worked for a newspaper in Ethiopia. Nicole is the recipient of a European Research Council grant that examines the role of social media in conflict and migration, with a specific focus on the Somali territories. Her work has appeared in journals such as African Affairs, Third World Quarterly, Review of African Political Economy and the International Journal of Communications. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Limnologica 65 (2017) 61–75

Limnologica 65 (2017) 61–75 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Limnologica journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/limno Farmers’ awareness and perception of Lake Ziway (Ethiopia) and its MARK watershed management ⁎ Hayal Destaa,b, , Brook Lemmab,c, Till Stellmacherd a Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU), Leopoldstr. 11a, D-80802, Munich, Germany b Chair of Ecosystem Planning and Management, EiABC, Addis Ababa University, P. O. Box 518, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia c Department of Zoological Sciences, College of Natural Science, Addis Ababa University, P. O. Box 1176, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia d Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Walter-Flex-Str. 3, D-53113, Bonn, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The article examines how heads of farmers’ households perceive the socioeconomic benefits of Lake Ziway Watershed management (Ethiopia), the causes of its current degradation, and the state of land and water use management in its wa- Local perception tershed. The investigation was based on in-depth empirical field work including a survey with 635 heads of Awareness smallholder farmers’ households via interview using semi-structured questionnaires. Further, water abstraction Lake was estimated from three districts that border with the lake. Respondents believe that Lake Ziway provides a Water abstraction number of individual and collective benefits for local communities, private companies and public institution. They stated, however, that the lake is under pressure from the floriculture industry and other investment pro- jects, high population growth and subsequent expansion of settlements and irrigation farms, high applications of agrochemicals, soil erosion, uncontrolled water abstraction, and deforestation in the watershed. -

Full Report (Pdf)

Working Together The sharing of water and sanitation support services for small towns and villages A WELL study produced under Task 510 by Brian Reed WELL Water and Environmental Health at London and Loughborough Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK [email protected] www.lboro.ac.uk/WELL © LSHTM/WEDC, 2001 Reed, B.J. (2001) Working Together -the sharing of water and sanitation support services for small towns and villages WELL. Contents amendment record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Revision Description Date Signed 1 Draft final July 01 APC 2 Final 01/10/01 APC Designed and produced at WEDC Task Management by Andrew Cotton Quality Assurance by Andrew Cotton Cover photograph: Brian Reed (W/r Dirbe Ebrahem, village water committee member and w/r Likehesh Mengesha, tap attendant, Tereta, Ethiopia) WELL TASK 510 Working Together: draft final report Table of contents Table of contents...........................................................................................................................i List of tables................................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................................iii Summary .......................................................................................................................................1 -

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia a M Tigray a Afar M H U Amhara a Uz N M

35°0'0"E 40°0'0"E Administrative Region, Zone and Woreda Map of Oromia A m Tigray A Afar m h u Amhara a uz N m Dera u N u u G " / m r B u l t Dire Dawa " r a e 0 g G n Hareri 0 ' r u u Addis Ababa ' n i H a 0 Gambela m s Somali 0 ° b a K Oromia Ü a I ° o A Hidabu 0 u Wara o r a n SNNPR 0 h a b s o a 1 u r Abote r z 1 d Jarte a Jarso a b s a b i m J i i L i b K Jardega e r L S u G i g n o G A a e m e r b r a u / K e t m uyu D b e n i u l u o Abay B M G i Ginde e a r n L e o e D l o Chomen e M K Beret a a Abe r s Chinaksen B H e t h Yaya Abichuna Gne'a r a c Nejo Dongoro t u Kombolcha a o Gulele R W Gudetu Kondole b Jimma Genete ru J u Adda a a Boji Dirmeji a d o Jida Goro Gutu i Jarso t Gu J o Kembibit b a g B d e Berga l Kersa Bila Seyo e i l t S d D e a i l u u r b Gursum G i e M Haro Maya B b u B o Boji Chekorsa a l d Lalo Asabi g Jimma Rare Mida M Aleltu a D G e e i o u e u Kurfa Chele t r i r Mieso m s Kegn r Gobu Seyo Ifata A f o F a S Ayira Guliso e Tulo b u S e G j a e i S n Gawo Kebe h i a r a Bako F o d G a l e i r y E l i Ambo i Chiro Zuria r Wayu e e e i l d Gaji Tibe d lm a a s Diga e Toke n Jimma Horo Zuria s e Dale Wabera n a w Tuka B Haru h e N Gimbichu t Kutaye e Yubdo W B Chwaka C a Goba Koricha a Leka a Gidami Boneya Boshe D M A Dale Sadi l Gemechis J I e Sayo Nole Dulecha lu k Nole Kaba i Tikur Alem o l D Lalo Kile Wama Hagalo o b r Yama Logi Welel Akaki a a a Enchini i Dawo ' b Meko n Gena e U Anchar a Midega Tola h a G Dabo a t t M Babile o Jimma Nunu c W e H l d m i K S i s a Kersana o f Hana Arjo D n Becho A o t -

1. Program Description

FSCP-GIAF-ETHIOPIA GRANT APPLICATION GUIDE 1. Program Description Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA) is implementing the 34-month Farm Service Center Program (FSCP) in partnership with the GIZ Green Innovation Centres for the Agriculture and Food Sector in Ethiopia (GIAF-Ethiopia). The project will establish five private retail input supply stores known as Farm Service Centers (FSCs). These Ethiopian-owned and operated enterprises are designed to improve the productivity, food security and incomes of smallholder famers in the Arsi zone of Ethiopia by linking them to high-quality agricultural inputs and extension services. The project is strategically aligned to build the role of the private sector and is connected to CNFA’s other initiatives in Ethiopia, which also work in the development of FSCs. In addition, and in line with the larger GIAF-Ethiopia initiatives the project will establish FSCs in the following five woredas recommended by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Oromia Bureau of Agriculture - Hitosa, Lude-Hitosa, Arsi-Robe, Digelu-Tijo and Tiyo. The project will also focus on up-scaling of innovations and best practices for wheat and faba bean production. FSCP-GIAF-Ethiopia is a follow-on to the successful Commercial Farm Service Program, which piloted CNFA’s Farm Service Center (FSC) Model in Ethiopia for the first time. CNFA’s Farm Service Center Model is a market-based, private sector model that applies matching grants and training methodology to establish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that deliver farm supplies and services. FSCs are located in larger townships and serve as rural development centers that meet the needs of private farmers in their communities. -

(Tor) Assessment of Production, Economic and Social Impact of Interventions with Innovations on Selected Fa

Terms of Reference (ToR) Assessment of production, economic and social impact of interventions with Innovations on selected farms with wheat and faba bean production in Arsi 1. Background Ethiopia has very diverse bio-physical environment with a variety of ecosystems, with significant differences in climate, soil properties, vegetation types, agricultural potential, biodiversity and water resources. That results in different farming systems and farming products. The crop subsector which, on average, accounted for about 30 percent of GDP has been the major contributor to the growth of the agricultural value added during the period of the GTP (Growth and Transformation Plan). The productivity of major food crops (Cereals, Pulses, and Oil seeds) reached an annual average level of 17.6 quintal (100 kg) per hectare. Further increase in production and productivity of major crops will continue to be a priority in the next five years (2016-2020) by fully implementing strategies such as delivering effective extension services, supplying agricultural inputs and conducting famers training. The participation of several actors like international partners and private business will be encouraged and supported as well by the government. In general, during the period of the second Growth and Transformation Plan, objectives are broadly set in terms of increasing crop and livestock production and productivity, promoting natural resource conservation and utilization, ensuring food security and disaster prevention and preparedness. In this regard, the German -

Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Small Ruminant Brucellosis in Selected Districts of Arsi and East Shoa Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Vol. 9(19), pp. 1338-1344, 13 May, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/AJMR2015.7400 Article Number: 469C2C953254 ISSN 1996-0808 African Journal of Microbiology Research Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJMR Full Length Research Paper Seroprevalence and risk factors of small ruminant brucellosis in selected districts of Arsi and East Shoa zones, Oromia region, Ethiopia Abiot Deddefo1*, Tesfaye Sisay2 and Getachew Tuli3 1Agricultural Research Institute, Adama Science and Technology University, P.O.Box-193, Asella, Ethiopia. 2Institute of Biotechnology, Addis Ababa University, P.O.Box-1176, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 3Sebeta National Animal Health Diagnostic and Investigation Center, P.O.Box-04, Sebeta, Ethiopia. Received 28 January, 2015; Accepted 7 May, 2015 A cross-sectional study was conducted in two districts in Arsi zone and one district in East Shoa zone, Ethiopia, to determine seroprevalence and assess the possible risk factors associated with small ruminant brucellosis. A total of 840 blood samples (409 sheep and 431goats) were collected. All sera samples were screened by modified Rose Bengal Test (mRBT) and all positive reactors were further tested by indirect enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA) test for confirmation. All 39 (4.6%) mRBT positive samples tested positive in iELISA. The individual animal and herd level seroprevalences of small ruminant brucellosis in the study area were 4.6 and 26%, respectively. Individual animal and herd level seroprevalences were highest in Adami Tulu-Jido Kombolcha district in East Shoa and lowest in Dodota Sire district in Arsi zone but differences were not statistically significant. In univariate logistic regression, statistically significant difference in seropositivity were found between different age groups, pregnancy status and parity number but not between flock size, species and sex. -

Preconditions for a Payment for Environmental Services Establishment at Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia

Wageningen University - Department of Social Sciences MSc. Thesis Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Group Preconditions for a Payment for Environmental Services establishment at Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia By Jean Carlo Rodriguez de Francisco Supervisors: Dr. Ir. Petra Hellegers Dr. Huib Hengsdijk Dr. Hans Peter Weikard MSc. Environmental Sciences May, 2008 Wageningen, the Netherlands Wageningen University - Department of Social Sciences MSc. Thesis Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Group Preconditions for a Payment for Environmental Services establishment at Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia ENR-80436 Jean Carlo Rodriguez de Francisco [email protected] Supervisors: Dr. Ir. Petra Hellegers Landbouw Economisch Instituut (LEI) [email protected] Dr. Huib Hengsdijk Plant Research International [email protected] Dr. Hans Peter Weikard Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Group Wageningen University [email protected] Keywords: Payment for environmental services, institutional environment, irrigation, urban water use, Ethiopia. ©Copy or recitation of this thesis or part of it is only allowed with permission of the supervisors. 2 Acknowledgements Praises and thanks to the lord for giving me strength and determination to walk forward in life trying to be a better man. Many people and organizations have contributed directly and indirectly to complete my research. First I would like to express my sincere gratefulness to Dr. Ir. Petra Hellegers from the Landbouw Economisch Instituut (LEI), because she gave me the opportunity to join in this research and provide me with financial support to undertake my research in Ethiopia as a part of my MSc. thesis and internship. Her guidance and constructive criticism helped me bring to a better ending the results here presented. -

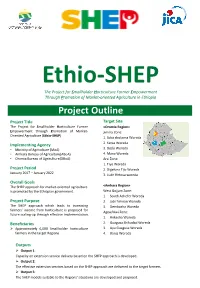

Ethio-SHEP Project Outline

Ethio-SHEP The Project for Smallholder Horticulture Farmer Empowerment Through Promotion of Market-oriented Agriculture in Ethiopia Project Outline Project Title Target Site The Project for Smallholder Horticulture Farmer <Oromia Region> Empowerment through Promotion of Market- Jimma Zone: Oriented Agriculture (Ethio-SHEP) 1. Seka chokorsa Woreda Implementing Agency 2. Kersa Woreda • Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 3. Dedo Woreda • Amhara Bureau of Agriculture(ABoA) 4. Mana Woreda • Oromia Bureau of Agriculture(OBoA) Arsi Zone: 1. Tiyo Woreda Project Period 2. Digeluna Tijo Woreda January 2017 – January 2022 3. Lude Hetosa woreda Overall Goals The SHEP approach for market-oriented agriculture <Amhara Region> is promoted by the Ethiopian government. West Gojjam Zone: 1. South Achefer Woreda Project Purpose 2. Jabi Tehnan Woreda The SHEP approach which leads to increasing 3. Dembacha Woreda farmers' income from horticulture is proposed for Agew/Awi Zone: future scaling-up through effective implementation. 1. Ankesha Woreda Beneficiaries 2. Guagusa Shikudad Woreda ➢ Approximately 6,000 Smallholder horticulture 3. Ayu Guagusa Woreda farmers in the target Regions 4. Banja Woreda Outputs ➢ Output 1: Capacity on extension service delivery based on the SHEP approach is developed. ➢ Output 2: The effective extension services based on the SHEP approach are delivered to the target farmers. ➢ Output 3: The SHEP models suitable to the Regions' situations are developed and proposed. Concept of SHEP Approach Promoting “Farming as a Business” Empowering and motivating people Sharing information among market actors & farmers for Three psychological needs to motivate people improving efficiency of local economies Autonomy Market Info. People need to feel in control of (variety, price, Market their own behaviors and goals season, etc.) Family budgeting Survey by Farmers farmers Competence Sharing SHEP People need to gain mastery market Linkage of tasks and learn different information forum skills Relatedness Market actors Producer Info.